2015 - Bangor University

advertisement

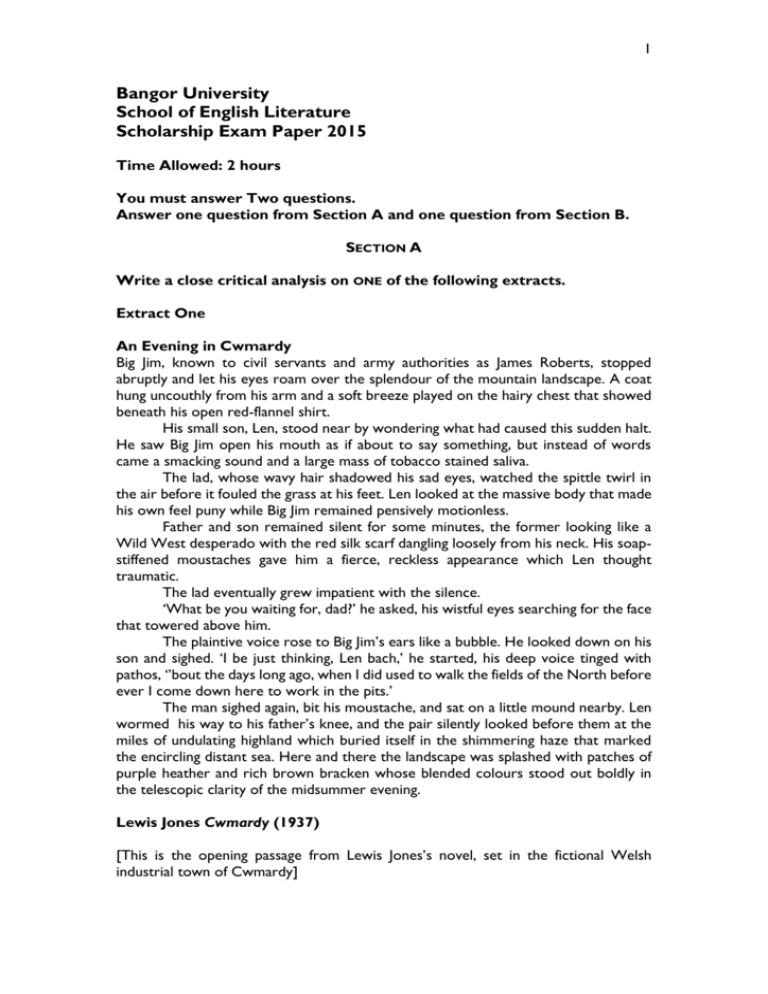

1 Bangor University School of English Literature Scholarship Exam Paper 2015 Time Allowed: 2 hours You must answer Two questions. Answer one question from Section A and one question from Section B. SECTION A Write a close critical analysis on ONE of the following extracts. Extract One An Evening in Cwmardy Big Jim, known to civil servants and army authorities as James Roberts, stopped abruptly and let his eyes roam over the splendour of the mountain landscape. A coat hung uncouthly from his arm and a soft breeze played on the hairy chest that showed beneath his open red-flannel shirt. His small son, Len, stood near by wondering what had caused this sudden halt. He saw Big Jim open his mouth as if about to say something, but instead of words came a smacking sound and a large mass of tobacco stained saliva. The lad, whose wavy hair shadowed his sad eyes, watched the spittle twirl in the air before it fouled the grass at his feet. Len looked at the massive body that made his own feel puny while Big Jim remained pensively motionless. Father and son remained silent for some minutes, the former looking like a Wild West desperado with the red silk scarf dangling loosely from his neck. His soapstiffened moustaches gave him a fierce, reckless appearance which Len thought traumatic. The lad eventually grew impatient with the silence. ‘What be you waiting for, dad?’ he asked, his wistful eyes searching for the face that towered above him. The plaintive voice rose to Big Jim’s ears like a bubble. He looked down on his son and sighed. ‘I be just thinking, Len bach,’ he started, his deep voice tinged with pathos, ‘’bout the days long ago, when I did used to walk the fields of the North before ever I come down here to work in the pits.’ The man sighed again, bit his moustache, and sat on a little mound nearby. Len wormed his way to his father’s knee, and the pair silently looked before them at the miles of undulating highland which buried itself in the shimmering haze that marked the encircling distant sea. Here and there the landscape was splashed with patches of purple heather and rich brown bracken whose blended colours stood out boldly in the telescopic clarity of the midsummer evening. Lewis Jones Cwmardy (1937) [This is the opening passage from Lewis Jones’s novel, set in the fictional Welsh industrial town of Cwmardy] 2 Extract Two "Dark human shapes could be made out in the distance, flitting indistinctly against the gloomy border of the forest, and near the river two bronze figures, leaning on tall spears, stood in the sunlight under fantastic headdresses of spotted skins, warlike and still in statuesque repose. And from right to left along the lighted shore moved a wild and gorgeous apparition of a woman. "She walked with measured steps, draped in striped and fringed cloths, treading the earth proudly, with a slight jingle and flash of barbarous ornaments. She carried her head high; her hair was done in the shape of a helmet; she had brass leggings to the knee, brass wire gauntlets to the elbow, a crimson spot on her tawny cheek, innumerable necklaces of glass beads on her neck; bizarre things, charms, gifts of witchmen, that hung about her, glittered and trembled at every step. She must have had the value of several elephant tusks upon her. She was savage and superb, wild-eyed and magnificent; there was something ominous and stately in her deliberate progress. And in the hush that had fallen suddenly upon the whole sorrowful land, the immense wilderness, the colossal body of the fecund and mysterious life seemed to look at her, pensive, as though it had been looking at the image of its own tenebrous and passionate soul. "She came abreast of the steamer, stood still, and faced us. Her long shadow fell to the water's edge. Her face had a tragic and fierce aspect of wild sorrow and of dumb pain mingled with the fear of some struggling, half-shaped resolve. She stood looking at us without a stir and like the wilderness itself, with an air of brooding over an inscrutable purpose. A whole minute passed, and then she made a step forward. There was a low jingle, a glint of yellow metal, a sway of fringed draperies, and she stopped as if her heart had failed her. The young fellow by my side growled. The pilgrims murmured at my back. She looked at us all as if her life had depended upon the unswerving steadiness of her glance. Suddenly she opened her bared arms and threw them up rigid above her head, as though in an uncontrollable desire to touch the sky, and at the same time the swift shadows darted out on the earth, swept around on the river, gathering the steamer into a shadowy embrace. A formidable silence hung over the scene. "She turned away slowly, walked on, following the bank, and passed into the bushes to the left. Once only her eyes gleamed back at us in the dusk of the thickets before she disappeared.” Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness (1899) [This is a passage from Conrad’s Heart of Darkness in which Marlow, the narrator, describes his experiences on board a ship sailing up the river Congo in Africa.] 3 Extract Three Chapter I There was no possibility of taking a walk that day. We had been wandering, indeed, in the leafless shrubbery an hour in the morning; but since dinner (Mrs. Reed, when there was no company, dined early) the cold winter wind had brought with it clouds so sombre, and a rain so penetrating, that further out-door exercise was now out of the question. I was glad of it: I never liked long walks, especially on chilly afternoons: dreadful to me was the coming home in the raw twilight, with nipped fingers and toes, and a heart saddened by the chidings of Bessie, the nurse, and humbled by the consciousness of my physical inferiority to Eliza, John, and Georgiana Reed. The said Eliza, John, and Georgiana were now clustered round their mama in the drawing-room: she lay reclined on a sofa by the fireside, and with her darlings about her (for the time neither quarrelling nor crying) looked perfectly happy. Me, she had dispensed from joining the group; saying, “She regretted to be under the necessity of keeping me at a distance; but that until she heard from Bessie, and could discover by her own observation, that I was endeavouring in good earnest to acquire a more sociable and childlike disposition, a more attractive and sprightly manner— something lighter, franker, more natural, as it were—she really must exclude me from privileges intended only for contented, happy, little children.” “What does Bessie say I have done?” I asked. “Jane, I don’t like cavillers or questioners; besides, there is something truly forbidding in a child taking up her elders in that manner. Be seated somewhere; and until you can speak pleasantly, remain silent.” A breakfast-room adjoined the drawing-room, I slipped in there. It contained a bookcase: I soon possessed myself of a volume, taking care that it should be one stored with pictures. I mounted into the window-seat: gathering up my feet, I sat cross-legged, like a Turk; and, having drawn the red moreen curtain nearly close, I was shrined in double retirement. Folds of scarlet drapery shut in my view to the right hand; to the left were the clear panes of glass, protecting, but not separating me from the drear November day. At intervals, while turning over the leaves of my book, I studied the aspect of that winter afternoon. Afar, it offered a pale blank of mist and cloud; near a scene of wet lawn and storm-beat shrub, with ceaseless rain sweeping away wildly before a long and lamentable blast. Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre (1847) [This is the opening passage from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, a novel in which a young girl in Victorian England describes her growth and development.] [END OF SECTION A] 4 SECTION B Write a close critical analysis of ONE of the following poems. In your answers you may wish to discuss some of the following aspects in each poem (but you are not limited to them): love; desire; death; gender; the speaker; tone and mood; style and technique; imagery. Poem One Sonnet 130 My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun; Coral is far more red than her lips' red; If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun; If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head. I have seen roses damask'd, red and white, But no such roses see I in her cheeks; And in some perfumes is there more delight Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks. I love to hear her speak, yet well I know That music hath a far more pleasing sound; I grant I never saw a goddess go; My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground: And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare As any she1 belied with false compare. William Shakespeare (c. 1564-1616) 1 she: a woman, i.e., ‘as any woman belied with false compare’. 5 Poem Two In an Artist's Studio One face looks out from all his canvases, One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans: We found her hidden just behind those screens, That mirror gave back all her loveliness. A queen in opal or in ruby dress, A nameless girl in freshest summer-greens, A saint, an angel - every canvas means The same one meaning, neither more nor less. He feeds upon her face by day and night, And she with true kind eyes looks back on him, Fair as the moon and joyful as the light: Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim; Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright; Not as she is, but as she fills his dream. Christina Georgina Rossetti (1830-1894) 6 Poem Three Not Waving but Drowning Nobody heard him, the dead man, But still he lay moaning: I was much further out than you thought And not waving but drowning. Poor chap, he always loved larking And now he’s dead It must have been too cold for him his heart gave way, They said. Oh, no no no, it was too cold always (Still the dead one lay moaning) I was much too far out all my life And not waving but drowning. Stevie Smith (1902-1971)