Jonson Lecture, 03.22.14 - Philadelphia Theological Institute

advertisement

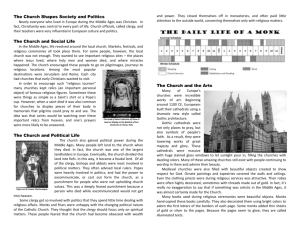

1 Lecture at The Augustana Institute at the Lutheran Theological Seminary, Philadelphia, March 22, 2014 by Bishop Emeritus, Dr Jonas Jonson. Archbishop Nathan Söderblom: Ambassador for Peace and Christian Unity Nathan Söderblom (1866–1931) was born in a pastor’s family at Trönö in northern Sweden, studied theology in Uppsala and served as pastor to the Swedish congregation in Paris 1894–1901. He defended his doctoral thesis on ancient Persian religion at the Protestant faculty of the Sorbonne, and was appointed professor of ”Theological Propaedeutics and Theological Encyclopedia” at the Uppsala university in 1901. For two years he also taught History of Religion in Leipzig, Germany, before he was elected Archbishop in the Church of Sweden in 1914. In 1925 he organized the Universal Christian Conference on Life and Work in Stockholm. In 1930 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Price. When he died in 1931, he was known as the outstanding leader of world Protestantism, sometimes referred to as ”the pope of the North”. He was married to Anna Forsell. Together they had twelve children, ten of them surviving him.1 1. On November 10th 1923, the Luther Society in Philadelphia gave a banquet in honor of Archbishop Nathan Söderblom. He was on a tour in the USA at the invitation of the Augustana Synod and the Church Peace Union. Having inaugurated new buildings at Augustana College in Rock Island and celebrated the heroic defender of the Reformation King Gustaf II Adolf with the students on November 6th, Söderblom proceeded to Detroit, Pittsburgh, Baltimore and Philadelphia. Everywhere he was preaching, speaking and lecturing. During his ten weeks in America, he spoke publicly no less than 120 times, “two months with a voice, one without” as he put it. In New York and San Francisco, Chicago and Minneapolis, churches were crowded. Lecture halls at Berkeley, Harvard, Johns Hopkins and Yale were filled by attentive students as he addressed fundamental issues in the history of Religion. He was received as the celebrity he was, and his visit was concluded with a meeting with President Coolidge in the White House.2 1 The most recent biography telling Söderblom’s life story is Jonas Jonson, ”Jag är bara Nathan Söderblom, satt till tjänst”. En berättelse om vilja och förtröstan att göra det omöjliga. Verbum förlag, Stockholm 2014. 2 Nathan Söderblom, Från Upsala till Rock Island. En predikofärd i Nya världen, Stockholm 1924, contains most of the sermons, lectures and talks given in the USA, as well as his personal impressions and memories. 2 He took every opportunity to plant his vision for world peace and Christian unity. The American Lutheran churches had not been very responsive to any interdenominational initiatives, and in 1908 they had resolved to stay outside the Federal Council of the Churches of Christ in America. In Europe, Lutherans had formed their own confessional organization. The German Allgemeine Evangelish-Lutherische Konferenz gradually had included both Scandinavian and American participants and was gaining influence, but Söderblom had not felt particularly welcome. In spite of his conservative and pietistic backgrund, his reputation as a Luther scholar and his position as archbishop of the biggest of all Lutheran churches, the AELK and its successor the Lutheran World Convention were inclined to write him off as being too “liberal” and too “catholic” at the same time. This was Söderblom’s dilemma. From the depth of his heart he believed that Luther’s experience and interpretation of justification was God’s gift and revelation to Christianity as a whole. Lutheran churches therefore had an invaluable contribution to make through the emerging ecumenical movement and they would balance the AngloSaxon dominance. But instead of confidently participating, they tended to keep their treasure to themselves. Many Lutheran churches were loaded with dogmatic orthodoxy, pietistic quietism, and what we today would label fundamentalism. The onslaught of modern theology with its historical-critical reading of the Bible, had reinforced the confessionalistic Lutheran attitude. For Söderblom, who was organizing his Life & Work conference to be held in Stockholm in 1925, it was of highest priority to get the Lutheran churches onboard. Therefore he had chosen to travel to America under the auspices of the Augustana Synod rather than the Federal Council. He had spent the post-war years strategically building inter-church relationships. He created a “block” of Lutheran churches around the Baltic Sea. Through massive and imaginative efforts to bring relief to the German people who were suffering from mass starvation because of the post-war blockade and by participating in a number of Lutheran church assemblies, he had won the grateful confidence of both the new German government and of the Landeskirchen who were pragmatically republican but monarchical in heart. He had continued developing a number of close personal contacts in the Church of England. But suddenly in February 1923, it looked as though his patient diplomacy was all wrecked. The Swedish bishops had made a sharp appeal addressed to the French government but particularly to President Warren Harding that the French 3 occupation of Ruhr must come to an end. It was a plea made in the hope that the United States would change its isolationist policy, a concern which Söderblom shared with Reinhold Niebuhr.3 The reaction in France was very strong: President Poincaré sent a six-page telegram to Söderblom defending the French action, and relations with the Federation of Protestant Churches in France were interrupted for a year. In Germany, on the other hand, Söderblom was much praised, and consequently he was accused of being decidedly pro-German. There is no evidence that his appeal hade any lasting effect on political authorities in the United States. Thus it was that his 1925 conference hung by a thread. Söderblom went to America in the midst of the turbulence that his appeal had caused. His mission was not only to encourage the Federal Council and the Church Peace Union, who was already fully involved with his conference, but to convince the American Lutheran churches to participate. This was his agenda also when he met with the Luther Society of this city. He delivered a lecture on the universal significance of Luther while his audience leaned back and enjoyed an after dinner smoke.4 Again he was successful: at Uppsala in 1925 both the United Lutheran Church and the Augustana Synod were represented at the highest level. 2. Söderblom had already served as Archbishop for nine years when he arrived here. He had been elected to his office by an extremely narrow margin without a single vote from his fellow bishops to be, and hardly any from the clergy of his diocese. But as the Archbishop’s office was combined with the office of vice chancellor at the university, professors also had a say. It was the faculties of arts and science who eventually paved his way. The fact that he was appointed was, one would say, “a providential accident”. At the time when it happened, he was serving as professor of History of Religion at the University of Leipzig in Germany. In the same week that World War I began he returned 3 Wolfram Weisse, ””Irenic Mediator for Unity – Partisan Advocate for Truth. Nathan Söderblom’s Initiatives for Peace and Justice”. Svenska kyrkans forskningsråd: Tro och Tanke 1993:7, Uppsala, pp.15 – 42. 4 While in Philadelphia he also preached at Gloria Dei on ”The eternal life”, at Holy Communion Church on ”Our vocation as Lutherans” and on ”Worship in solitude”. He spoke at the Gustavus Adolphus church on ”The evangelical heritage of the Swedish people”, and addressed the American section of Life & Work on ”The urgent task of the Church today”. He lectured at the University of Pennsylvania on Buddhist and Christian temptation stories, and addressed the conference of the World Alliance for Promoting International Friendship through the Churches. He also visited the old Swedish churches along the Delaware River. All in four days! 4 to Uppsala. He barely made it on trains overcrowded with cheerful young soldiers on their way to battle. Among them were some of his most gifted students who would be dead within weeks. Söderblom was internationally widely known as a scholar of religion. He had earned his doctorate at the Sorbonne and had taught as professor at Uppsala since 1901. History of Religion was a comparatively new field of study, and with his phenomenological approach he had gained a great academic reputation. In his lifetime he was awarded no less than fourteen honorary doctorates, and he concluded his academic career by delivering the prestigious Gifford lectures at Edinburgh just before he died in 1931.5 Becoming an archbishop, his life took a new turn, which he experienced as God’s direct and personal call. In the early 20th century, the idea was widely spread that individual personalities – explorers, scientists, political and religious leaders, artists, and even successful businessmen – were chosen to lead the progress of humanity. Söderblom shared this personalistic understanding of history, and he often referred to great personalities as geniuses or even saints. There is no doubt that he regarded his providential election as a confirmation that he himself was chosen for a particular ministry of reconciliation, unity and peace. He was determined to make full use of his position as archbishop to fulfill this vocation at a momentous time. For this purpose he did not hesitate to inflate the archiepiscopal see of Uppsala in the eyes of the world and put it on par with Canterbury and even with Constantinople and Rome. His consecration on November 8th 1914 – just one hundred years ago – was planned as a magnificent ecumenical manifestation, but the war prevented most foreigners from attending. The Augustana Synod, however, was represented at the occasion, and Söderblom made it a special point to have Dr L. G. Abrahamson as the only non-Swedish assistant participate in the laying on of hands. Nine years later Söderblom had established himself as the most charismatic, open minded and energetic archbishop the Church of Sweden had had since the Reformation. But he remained controversial, theologically and politically. He was, no doubt, a genuine liberal theologian in the line of Albrecht Ritschl, and in addition a 5 Eric J. Sharpe, Nathan Söderblom and the Study of Religion. The University of North Carolina Press 1990. The most reliable and thorough intellectual biography of Söderblom in recent years is Dietz Lange, Nathan Söderblom und seine Zeit, Göttingen 2011. This book rendered the author an honorary degree of theology at Uppsala in 2014. 5 person highly committed to social justice. His opponents would look at him not only as a self-indulgent heretic, but as a kind of a socialist using his platform for opinion-making and social change. He was indeed sympathetic with the labor movement, but his social thought had not been shaped by Marxist socialism. He was, rather, influenced by Christian social movements in the USA, France and Germany during the 1890s. Somewhat paradoxically, he received most of his moral and financial support for ecumenical ventures not from the churches but from the old landed aristocracy and new industrialists who had accumulated much wealth from export to war ridden countries of Europe. Söderblom was a rich and complex character, deeply spiritual, a mystic and an activist at the same time, ascetic and extravagant, an actor with close friends among artists and authors, a first class musician and a master of rethoric. He possessed an unforgettably resonant voice, which both attracted and in the end captivated his hearers. His speaking, preaching and lecturing were irradiated with joy and hope, and occasionally he would spontaneously start singing in the midst of a talk as he did to a large audience upon his arrival in New York. But there was also another side. His brilliant gifts were held together by a strong will and a demanding discipline, at times characterized as “inhuman”. He was very fond of the metaphor of race-horse and rider to express his ideal: “The good horse can achieve its highest capacity and its greatest speed only under the firm hand of the rider. So it is with the soul. Only under the firm hand and the strict bridle of God can the soul be encouraged to give its best”. Considering Söderblom’s simple background as the son of a rural pastor, he moved with remarkable confidence and disarming humility and humor among all kinds of people, be they peasants, academics, statesmen or royalty. After seven years in Paris, his French was perfect. His German was flawless and his English good enough to arouse admiration. He gladly used Latin, daily read his Greek New Testament, and when consecrating Baltic bishops he addressed them in Estonian or Latvian. Nobody doubted his extraordinary intellectual capability, but he was more admired for his work capacity. To him time seemed to have no limits. His dense program on his tour in the US is sufficient to prove the point, even more so as he had been down with a heart attack not long before. His ecumenical vision was shaped early, through the Student Missionary Association at the University of Uppsala in the 1880s and more particularly at a student conference at Northfield, Massachusetts in the summer of 1890. He arrived there as a 6 “born again” Christian, was profoundly impressed by Dwight L. Moody and Ira Sankey, and made friends with John R. Mott and Winfred Monod, who thirty years later would become his close collaborators. In New England he first encountered the kind of energetic Anglo-Saxon supranational Christendom, out of which the modern ecumenical movement sprang. At a meeting with Newman Smyth, who later wrote the important book Passing Protestantism and Coming Catholicism, he jotted down a prayer, which guided him through his life: “Lord, give me humility and wisdom to serve the great cause of the free unity of Thy Church”. 3. When he took on leadership in the ecumenical movement, he was well prepared. He had lived in France, visited Britain often, and taught in Germany. He was part of an impressive network of personal relations; his correspondence was already voluminous. In 1909 he negotiated an agreement with the Church of England on inter-communion and this had influenced his ecclesiology. In 1911 he spent a couple of weeks in Rome and Athens on his way to a conference in Constantinople of the World Student Christian Federation. For the first time he experienced the living liturgy of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches. Gradually, his ecumenical vision and vocation matured. Experiencing first hand how the war disrupted Christian culture and overnight turned brothers into enemies, he felt compelled to act. He mobilized all his perseverance, diplomatic skill and social competence to make European and American Christians meet and rebuild confidence. The worst obstacle was the enmity and mutual accusations that prevailed between the French and the Germans -- unless the Germans admitted their guilt for the war, the French would not see them face to face. With the unfair treaty of Versailles under the auspices of President Wilson, the situation grew worse. It was Söderblom’s greatest diplomatic achievement that he succeeded in bringing the enemies together in Stockholm 1925. A year later they were prepared to leave la Schuldfrage (as it was called) behind. Already before his consecration, at his own initiative, had prepared an appeal for peace to be distributed among church leaders all over the western world with the hope that they would sign. The words flowed out of his troubled heart: “The War is causing untold distress. Christ’s Body, the Church, suffers and mourns. Mankind in its need cries out: O Lord, how long?” He could not but remind “especially our Christian 7 brethren of various nations that war cannot sunder the bond of internal union that Christ holds in us” and call upon God that “he may destroy hate and enmity, and in mercy ordain peace for us”. He secured the signatures of Dr. Charles MacFarland and Professor Shailer Mathews on behalf of the Federal Council, and also of church leaders in the Netherlands, Switzerland and the Scandinavian countries. To his disappointment churchmen in the belligerent countries refused to put their names to the document. Only a few months into the war, the national war frenzy, to which preachers had made no small contribution from pulpit and rostrum, already ruled out any church cooperation for peace. Söderblom was filled with affection for France, Germany and England. He had personal friends on both sides of the trenches. And at the heart of his faith was the cross of Christ, and he was deeply convinced that reconciliation with God and the unity of the church were conditional for peace. Therefore he pursued with almost superhuman patience and energy his attempts to make Christians defy hostility and seek unit. While fulfilling his many episcopal duties in the large Uppsala Diocese and in the Church of Sweden, he made one attempt after the other to reach out to churches with an invitation to meet and to cooperate for the sake of peace. But only after the war was he able to get the process started which led up to the Universal Christian Conference on Life and Work in Stockholm 1925.6 4. Söderblom´s goal, strategy and tactics developed as he moved along. He pragmatically adapted himself to the rapidly changing political situation, but he never lost his focus on furthering peace by uniting the churches and strengthening international law and arbitration. His theological presumptions remained the same. The first was that God is a living God, revealing himself through prophets, historical events, and in all authentic religion, and acting through individual persons who put their lives at God’s disposal. The second was that the church as a “body” or an organization may take a multitude of forms, but that the “spirit” is one and the same. The unity of the universal church is a unity in spirit, and a unity in diversity. Söderblom consistently rejected uniformity in doctrine 6 The outstanding study of Söderblom’s ecumenical journey is Bengt Sundkler, Nathan Söderblom. His Life and Work. Uppsala 1968. Nils Karlström, Kristna samförståndssträvanden under världskriget 1914 – 1918, Stockholm 1947, is an impressive and detailed study of Söderblom’s contribution. This dissertation is summarized in Ruth Rouse and Stephen Neill, eds., A History of the cumenical Movement 1517 – 1948, Geneva 1953, pp. 509 – 542. See also Wolfram Weisse, Praktisches Christentum und Reich Gottes: Die ökumenische Bewegung ”Life and Work” 1919 – 1937. Göttingen 1991. 8 and ministry as an ecumenical goal; he respected the individuality of each church as it was shaped by cultural circumstances. He was suspicious of incarnational theology as it easily could lead to institutionalism. The third presupposition was that all churches equally share in the catholicity of the one and holy and apostolic church. There was Orthodox catholicity, Roman catholicity and an Evangelical catholicity. No church had the right to claim to be more catholic than others and to pretend to be normative. For Söderblom, the episcopal ministry was both a sign and an instrument of such catholicity, and he spared no efforts to have episcopacy reintroduced where it had been lost. He saw to it that it was introduced in the Tamil Evangelical Lutheran Church in India. He ordained bishops in Estonia, Latvia and Slovakia and also made an effort to convince Kaiser Wilhelm II personally to have German superintendents ordained as bishops. What mattered to Söderblom was that bishops represented an unbroken continuity with the undivided church; his ecclesiology was shaped by his sense of history. To him the Reformation was exactly what the word says, not an interruption, but a renewal of the living tradition. As a child he had worshipped in the unaltered 14th Century church of Trönö, and he maintained a somewhat romantic understanding of medieval times. In the weeks before his appointment, he made a qualified study in liturgical history on the consecration of the first Archbishop of Uppsala, Stephen, in 1164. He had developed his thinking on evangelical catholicity when encountering the Church of England and was of the opinion that his own church had preserved its integrity in relation to the state and its continuity with the past even better than had the Anglicans. This made the Church of Sweden suitable to serve as a “bridge church” between traditions. But he never made apostolic succession a condition for communion, nor did he regard evangelical catholicity as a liturgical program. Reflecting on his own ministry, he would describe it by using the image of five concentric circles: his primary responsibility was his diocese, then the national Church of Sweden, thirdly Lutherans of Swedish descent in other countries, then other Lutherans, and finally the universal church. His visit with the Augustana Synod thus turned into a kind of episcopal visitation, and at the end of his tour he presented a number of suggestions as to how the relations between Augustana and the Episcopal Church should be organized. He would certainly have welcomed Augustana confirming its Swedish roots by ordaining bishops in the Swedish tradition. Söderblom did in fact participate in the laying on of hands when Gustaf Brandelle was installed as president of 9 the Synod, but Brandelle did not regard this as a consecration, nor did he ever use the pectoral cross which was later presented to him by the Swedish bishops. At a conference in Uppsala in 1917 with participants from the neutral countries, Söderblom formulated a conception of unity, which was later to be adopted by the Life and Work movement: When our Christian confession speaks of one Holy Catholic Church, it reminds us of that deep inner unity that all Christians possess in Christ and in the work of His Spirit in spite of all national and denominational differences. Without ingratitude or unfaithfulness to those special gifts in Christian experience and conception, which each community had obtained from the God of history, this Unity, which in the deepest sense is to be found at the Cross of Christ, ought to be realized in life and proclamation better than hitherto.7 The centre of unity is the cross of Christ, which transcends all earthly differences. The diversity of Christian traditions should not be obscured but should rather shine forth through the unity. That Christian unity “ought to be realized in life” not only constitutes the guiding principle for all of Söderblom’s further ecumenical efforts, but also qualifies what is meant by “evangelical catholicity”. At a time when Scandinavian and German Lutherans generally held church and nation identical, Söderblom – in spite of his love for Sweden and its particular history – consistently emphasized universality as the prime characteristic of the church. His mission was not to create unity between national churches, but to make the real but invisible unity of the universal church visible. If Christians worked together for the common good of humanity, their unity in faith would be revealed to the world and made real to themselves. He respected Faith and Order, but could not afford time to wrestle with dogmatic and liturgical problems when the world was in such disorder. His participation at Lausanne in 1927 was a failure. He was a man of action and exceedingly liberal in doctrinal matters. Truth was for him grounded not on dogmas but in personal experience. He had himself encountered the living God in a decisive moment of conversion, a direct experience of God’s holiness; since then trust and confidence were the characteristics of his seemingly unshakable faith. 7 Karlström 1947, p. 203; Bengt Sundkler, Nathan Söderblom. His Life and Work. Uppsala 1968, p. 203. 10 5. Söderblom lived at a time when world Christendom was thoroughly transformed by external and internal forces. Empires disintegrated, monarchies gave way to republics, German state churches became independent, and Russian Orthodoxy faced severe persecution. At the same time Christianity expanded rapidly in other continents and American denominationalism became the ecclesiological novelty. But faith itself was severely challenged by science and secular ideologies, and not least by the loss of credibility as “Christian” nations fought their devastating war. In an exceptional way, the Churches of Sweden and England were able to make their transition into modernity with structures comparatively intact. Uppsala and Canterbury therefore felt a particular responsibility as agents for peace and unity. Already in 1908, the Church of Sweden hade been invited to send an observer to the Lambeth Conference. In 1888 the ”Lambeth Quadrilateral” had been approved with four conditions for the re-union of churches. Since the Church of Sweden fullfilled all of those conditions, including the one on the historic episcopate, there had already been certain initiatives to establish formal relations.8 When the invitation to the Lambeth conference arrived, Söderblom – who at the time was a young professor – immediately grabbed the opportunity. In consultation with the Swedish archbishop, he secured the governmental approval required for official relations between the two state churches and arranged for a respected bishop with good command of English to be sent to the conference. He was well received. A few weeks later Söderblom himself went to England, met with the Archbishop of Canterbury Randall Davidson and a number of other bishops to make sure that a formal interchurch dialogue would be established. Already in 1909 an Anglican delegation arrived in Uppsala for – as far as I know – the first official ecumenical dialogue ever. As a result the Church of England fully recognized the episcopal order of the Church of Sweden, and in 1920 inter-communion was established, confirmed by the Swedish bishops two years later. At the conversations, the American Episcopal Church was also present, represented by Bishop G. Mott Williams of Marquette and the priest Gustaf Hammarskjöld, who was of Swedish decent. This caused a real problem. In the States the Swedish – Anglican contacts were not welcomed since the Augustana Synod feared that 8 Lars Österlin, Churches of northern Europe in profile: a thousand years of Anglo-Nordic relations. Canterbury 1995. 11 a rapprochement would strengthen American Episcopalian efforts to enlist Swedish immigrants. Söderblom had friends among Augustana’s leaders and was aware of the problem. Therefore he resolutely excluded Hammarskjöld from the negotiations and turned down Bishop Mott’s plea for Episcopal care of Swedish immigrants. With determination he defended the integrity of Augustana as “the Swedish church” in the USA. When he was visiting here fourteen years later the question of Episcopal – Augustana relations was raised again. Söderblom handled it with caution, but suggested that a couple of 17th century Swedish church buildings now in the hands of the Episcopal Church might be used by the Swedes. In a sermon at the Cathedral of St John the Divine in New York City he expressed the hope that the two churches would recognize each other and develop as good relations as had the Church of Sweden and the Church of England.9 Between the First and the Second Vatican Councils, the Roman Catholic Church was guided by reactionary ultramontanism. The popes had built a fortress against both liberal democracy and all forms of socialism. In the 1890s, Söderblom had come to know a number of catholic “modernists” in France who were condemned by the church, prevented from teaching, and in some cases excommunicated. The most influential among them was Albert Loisy. In 1910 Söderblom had published a most significant study on Roman Catholic modernism, which regrettably was never translated.10 Adding his immediate experience of ecclesiastical oppression and the limiting of intellectual freedom in the Catholic Church to his anti-institutional ecclesiology, it is not surprising that Söderblom often expressed a strong anti-Roman sentiment. This did not, however, prevent him from making every effort to invite the Roman Catholic Church to his conferences or to be touched by authentic Catholic spirituality. Participating in Holy Week services in Rome, he had a deep sense of what today is called “spiritual ecumenism”. The only answer he received to his invitations, however, was the unambigious non possumus. In 1928 the encyclical Mortalium animos charged the ecumenical movement with theological relativism and forbid Catholics to have anything to do with ecumenism. Only at the end of Söderblom’s life did he get the 9 Söderblom 1924, p. 368. Nathan Söderblom, Religionsproblemet inom katolicism och protestantism. Stockholm 1910. 10 12 opportunity to enter into a serious dialogue with a Jesuit scholar, Max Pribilla, on the conditions for Christian unity.11 At his visit to Constantinople in 1911, Söderblom purposely began to build relations with Orthodox Churches. His personal friendship with Metropolitan Germanos of Thyatira proved decisive for the Orthodox participation in the ecumenical movement. During the war, Söderblom maintained contact with the churches in the Balkans, Greece, Constantinople, Egypt and Russia through Swedish diplomats and relief workers, and he exerted a certain influence on the famous patriarchal encyclical of 1919, which prepared the way for the vulnerable Byzantine church to involve itself with the ecumenical movement.12 Including the Orthodox was not looked at with approval by most Protestant leaders, but it was essential for Canterbury. To achieve his goal, Söderblom at a planning conference in Geneva in 1920 – in his unpredictable manner – staged an appearance of several Orthodox bishops. The Protestants were taken by complete surprise and accepted the enlargement of their venture. 6. The Stockholm conference in 1925 was the fulfillment of Söderblom’s dreams and the incomparable event of his life. With more than 600 delegates, including a large number of Orthodox headed by Patriarch Photios of Alexandria, it was the most representative gathering of Christians since the ecumenical council of Nicaea 1600 years before. It was Söderblom’s affair altogether – one could say the conference was an extension of his personality. The program was overloaded, the actual results meager, and burning problems were swept under the carpet. Still it was a healing experience after a decade of strife and destruction, a new beginning. There was energy and vision, prayer and personal encounters, pomp and circumstance and a great hospitality in beautiful August weather. The expenses were mostly covered by Swedish donors. Among the stewards was a young man, Dag Hammarskjöld, for whom Söderblom was a mentor and a close family friend. Nothing like this meeting had ever happened before; participants could not find words for their emotion and inspiration. Used to thousands of big conventions 11 Nathan Söderblom, ”Pater Max Pribilla und die ökumenische Bewegung. Einige Randbemerkungen”. Kyrkohistorisk Årsskrift 1931, pp 1 – 99; Pater Max Pribilla, ”Drei Grundfragen der ökumenische Bewegung”. Kyrkohistorisk Årsskrift 1931, pp. 113 – 127. Uppsala. 12 George Tsetsis, ”Nathan Söderblom and the Orthodox Church”, Tro & Tanke 1993:7, Uppsala, pp.89 – 102. 13 and international conferences as we now are, we can hardly imagine what Stockholm was like. The universal church was gathered in all its exotic diversity. The world press was there, and Söderblom’s call for justice, peace and unity was amplified all over. In his own analysis of the conference, he concluded that the very fact that they all had met was the most significant achievement.13 The ecumenical movement, however limited in size, had begun to move. In spite of recurring health problems and an overload of responsibilities at home, the post-Stockholm years were filled with international assignments. Söderblom had become the great European of his time. He was invited to speak and to preach at all kinds of events all around Europe. The ecumenical council which he had aimed at since 1919, was formed only in 1930 and the World Council of Churches which he had foreseen was constituted in 1948. As his liberal theology was overrun by history, and systematic theologians like Gustaf Aulén and Karl Barth set a new tone, the ecumenical movement took a new course, but Söderblom was not forgotten. At a time when Christian values were compromised and Christian civilization was on the brink of complete bankruptcy, like an Old Testament prophet he reminded the churches of their calling, and like his admired saints St. Augustine, Jeanne d’Arch, Gustavus Adolphus and first and foremost Martin Luther he revealed the will, mercy and righteousness of God. His recognition of God’s revelation in all authentic religion, his consistent adherence to principles of justice, his promotion of binding international law, and his trust in a living God, continue to challenge world Christendom. Nathan Söderblom died a sudden but saintly death on July 8, 1931. Time and again, in many languages, he had repreated: “A saint is one who in his or her life shows that God lives.” Was he not one of them? 13 His own 950 page report Kristenhetens möte i Stockholm was published already in 1926. 14