deep freezer edits

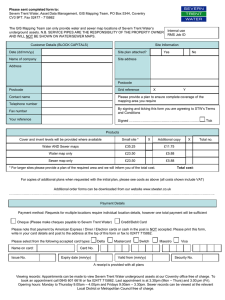

advertisement

Summertime That was a strange summer, after we found Oscar in the deep freezer with his arms around his knees and his eyes glassy and sad. “Oh Jesus,” Mallory said, “it’s the Mason boy, it’s that little boy, oh Christ Grace are you seeing what I’m seeing.” She flapped her fat hands. There was a yellowish stain on the lower-right hand corner of her apron. “Grace,” she said, calmer. “I don’t think I can move.” I took her by the arm and sure enough felt the bone petrified underneath. I looked around her into the freezer. Oscar’s eyes were open and patient, and a crystallized droplet of snot hung from the rim of his right nostril. A few hours before I had been on my break and stood outside the diner with my apron over my shoulder, smoking. We were in the belly of summer then and everything was wavering in the heat, the treetops huge, catching and throwing the three o’clock sunlight. Finley was standing a little ways away from me, looking into the restaurant with his hands stuffed in his pockets. “Is that a cigarette?” he asked. I didn’t say anything. Finley was small but hard, compact like an action figure of himself. When I thought of him I saw his face as that of a very old man. His eyes were small and light and anxious. I said, “I didn’t know you were working today.” “I’m picking up Trent’s shift. He’s at the clinic.” “What for?” “He’s waiting on Adda.” “So that’s that, then. She made up her mind.” “I mean it wouldn’t have gone any other way. We all knew she wouldn’t ’ve.” “I guess.” “Listen, what are you doing after work today?” It was the heat; it was making me feel funny. Back then I was always tired. “I don’t know. I’ll probably just go home.” “We’re going to the lake. You should come.” I waved at the Wethermeyers as they crossed the street, and they waved back. “Me and Trent. You should come.” “I don’t know,” I said. “I hear Mallory yelling. Do you hear that?” “Sure, sure,” he said. “Listen, I just, I really think you should come. Trent needs cheering up and all and I was going to invite Trish and Corey but they’re going to some party Trent’s not invited to on account of Adda.” “I’m going to go see what’s up with Mallory,” I said. “Hey, I’ll let you know about tonight.” Something about Finley had me treating him always with equal parts sympathy and condescension, creating a kind of delicate equipoise around which his sexual motives wove pity into expectation and had me dancing always on a razor’s edge. Mostly I just didn’t like him, and felt bad for him, and was mildly repulsed by his old man’s face and inexplicably small hands, fingernails fine as a child’s. I had known Oscar for only about six months, after I started work as an assistant at the public elementary school. The third-grade teacher, Miss Whitlock, hadn’t really known what to do with me. “You’re working here? As what?” “I don’t know, they just told me to come up here.” “What’s this for again? Community service?” “Yes ma’am. They said whatever you needed help with that’s what I’m here for.” “Well, all right.” She fluttered the whites of her eyes at the ceiling briefly. “Okay. I know what you can do.” We walked over to a side-table where a blond boy with round wire-rimmed glasses gazed with fixed intensity at a sheet of paper covered in test-score bubbles. “Oscar,” said Miss Whitlock, “this is Grace.” “Hi,” I said. Oscar looked up but said nothing. His hair was fine and cut straight across his forehead so little pink triangles of skin appeared beneath his bangs. Miss Whitlock lowered her voice. “Oscar’s taking a test to determine if he can stay in the third-grade math class, but he’s having trouble reading the questions because he’s dyslexic.” “Okay,” I said. “So maybe the thing to do is if you could read each question to him and then read each multiple-choice answer just so he has the general idea.” “Sure,” I said. I was relieved. The other kids in the room were running around and overturning their chairs and putting glue up their noses. The room smelled like warm saliva and hand sanitizer. Generous pity for Miss Whitlock filled my heart. By the time Mallory stopped crying and called the paramedics it had been maybe ten minutes since I came into the kitchen and the diners were beginning to crane their necks impatiently towards the kitchen door. Finley came in flushed with his cowlick down over his forehead, saw the blue shape in the freezer, and vomited unobtrusively into the sink. Mallory had pulled herself together and was dialing the emergency line. Tears ran down her face at random and fell onto her arms, the phone, the floor tiles. “That poor little boy,” she kept saying. “Oh Jesus that poor boy.” “I’ll go take care of the diners,” I said. “Will I, Mallory?” “Oh, go,” she said. “Get out of here. God, you’re fucking callous. Go on, get out.” I didn’t take offense. Emotions were running high. “Mrs. White said that she was born in the year one thousand, nine hundred forty two. In what year was she born?” I looked at Oscar. “Again?” “No thank you,” he said. His eyes seemed to go through the test sheet. His mouth worked silently as he looked at the booklet with the multiple-choice answers (A. 1429; B. 1492; C. 1924; D. 1942). After a minute, he darkened a bubble. “Ready?” “Yes.” “Okay. This one’s longer. Alonzo takes 56 steps from his house to Sherry’s house. He takes 22 more steps to walk from Sherry’s house to the store. How many steps does it take Alonzo to walk from his house to Sherry’s house from the store?” Silence. “Should I read it again?” “Yes please thank you.” There was a polite embarrassment evident only in the quickness of his reply. He wore a watch with snails decorating the quarter-hours; the snail on the twelfth hour sported a pair of sunglasses. The skin of his wrist was red and crimped with watchband-indentations. I read the question again. “Do you want to hear it one more time?” “No thank you.” “Are you sure?” “Yes I’m fine.” “Okay, then. Great.” When the big hand on the clock struck twelve-thirty, the kids went outside for recess and Oscar was allowed a ten-minute break. We both relaxed, leaned back in our seats. I took out a pack of crackers and offered him one, but he shook his head. “Do you feel good about the test?” I asked. He shrugged. “It doesn’t matter,” I said. “Either way it doesn’t matter. I don’t mean to say you’ll do badly or anything. But it doesn’t matter if you do. I don’t mean to make it sound like I think you’ll do badly. And if you do well, well that’s great, isn’t it? But just keep in mind, you know, these things, the outcomes don’t matter ultimately.” He took off his glasses and pinched the lens with his thumb and index finger through his shirt, and rubbed it clean. “Not to say you shouldn’t try. That’s important, don’t get me wrong. To be honest I wish I had tried a lot harder when I was in elementary school. You get all kinds of bad habits if you don’t work hard early on, I think. But then again I don’t know. You’re doing fine. Do you want a cracker?” I asked. “No, thank you,” he said. He finished cleaning his glasses and put them back on. He looked at me and his eyes were blue and peaceful. “I don’t think I’m doing very well,” he said. Miss Whitlock came back in. “Recess is almost over,” she said. “You two should probably start back up.” She glanced at me and then at the clock, and then at me again. “Are you all right?” she asked. Eventually it came out that what had happened was somehow he had wandered into the freezer and the door had swung shut and all seventy pounds of him couldn’t manage to shove it open again. The door was brushed steel and three inches thick and had a big swinging bolt that you had to leave hanging out so the door jammed itself open when you went inside for slabs of lamb and ice-crusted ham hocks and steaks the brutal color of a cut lip. No one offered an explanation as to how or why he had gotten back there in the first place. After work I went to the lake with Finley and Trent. I rode up front in Finley’s truck with my head on my elbow dangling out of the passenger-side window and my hair pulling wildly in the slipstream. We pitched the tent as the sun spread bloody and incandescent on the water and Trent searched his pockets for a lighter. “Can’t camp out without a fire,” he said. As he pushed sticks into a careful tent and slid pieces of redwood into the middle he seemed happy in a babyish way, his face huge and trusting and expectant, and when the flame caught and began to burrow into the wood I thought he looked like someone had given him a present he had been told he deserved. We sat around the fire. Trent told us about his day at the clinic. “You just wait outside and the walls are gray and hard to look at for too long. There weren’t so many guys like me, young guys. A couple guys who looked like dads—they looked at me like I was, you know, whatever, some kid. Some women were there too. Then Adda came out and I drove her home.” “Well, huh,” Finley said. “Jesus. Did she tell you what it was like, or what?” “She didn’t talk about it so much. She was pretty zonked. They give you all kindsa drugs—you know.” “Sure,” Finley said. “Sure, sure.” He put his weight on one foot, then the other. He bit the fleshy side of his thumb. “Did you bring anything to drink, or what?” We drank wine Trent had stolen from his father’s liquor cabinet and the fire took on a mystical quality. I thought I was being told things, big things, and grew impatient with Finley and Trent, who understood nothing. For an hour we watched the fire and then Trent fell asleep, his mouth slightly pursed as though he was about to coo or blow a bubble of saliva. I walked past him, barefoot down on the milky pebbles that lined the beach and Finley followed me. We stood and watched the water move. “That was crazy today,” he said. “So sad.” The lake made little noises as it pulled weakly at the shore. Evening shadows broke the light and made everything look sort of sideways. It was getting cold and I crossed my arms, tucked my hands under my armpits. The mystical flush of knowledge had warped soggily into a headache. “You knew him, right? I mean, not just like knew him but talked to him. Right? Didn’t you say something about him way back?” “Yeah, I guess,” I said. “I don’t want to talk about it.” He was quiet. We looked out over the water. Then he turned me towards him and started kissing me. “This is okay, right?” he said. “Is this okay?” “Sure,” I said. Just then I felt so lonely I could hardly stand it.