Enlarge image

advertisement

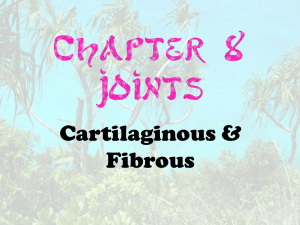

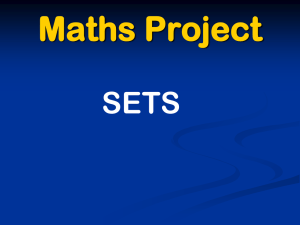

Name:______________________ Ancient Civilizations Date:___________________ Move Over, Lucy; Ardi May Be Oldest Human Ancestor by CHRISTOPHER JOYCE October 01, 200912:07 PM Listen to the Story All Things Considered 4 min 32 sec Enlarge image An artist's rendering of what Ardipithecus ramidus, aka "Ardi," may have looked like. This female stood about 1.2 meters, or about 4 feet, tall. J.H. Matternes Scientists on Thursday unveiled a fossil human ancestor dating back 4.4 million years — a creature more ancient than the famous fossil "Lucy." And, the scientists say, even more important than Lucy. The team that discovered the fossil, called Ardipithicus ramidus, say it's the closest thing yet found to the common ancestor of both chimps and humans. That common ancestor is thought to have lived about 6 million years ago. From that animal, chimps and other apes evolved in one direction, while our own ancestors, the hominids, evolved through several forms into what we are now. The anthropologists found the bones in Ethiopia, in a desert region called Aramis. Scientists have previously discovered a few teeth and bones of Ardipithicus, dating from 5 to 6 million years ago. But in this case, they have more than 100 bones from 36 individuals, including a partial skeleton of a female whom they've dubbed "Ardi." The area excavated "was a time capsule with contents that nobody had ever seen before," says anthropologist Tim White, of the University of California, Berkeley, and the team co-leader. Enlarge image (Below) The area in Ethiopia where "Ardi" was found. The region is rich in hominid fossil sites. Science/AAAS Enlarge image (Right) Dr. C. Owen Lovejoy, Kent State University professor of anthropology, stands next to the reconstructed skeleton of "Lucy." A team of researchers including Lovejoy have discovered a skeleton older than "Lucy," nicknamed "Ardi." Kent State University Name:______________________ Ancient Civilizations Date:___________________ The skull had been crushed into scores of pieces, says White. But after years of reconstruction work, White says, "what we have is a very small-brained cranium of an early female hominid that is very different from a chimpanzee." That's critical, White says. "People have sort of assumed ... that the last common ancestor was more or less like a chimpanzee." Ardi suggests otherwise — that in fact the earliest known hominid was a "mosaic," with some features like chimps but others like monkeys, such as the feet. Other features are more like the more recent hominid, Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis), such as the teeth. For example, the canine teeth near the front of the mouth in both male and female Ardipithicus are much smaller than a chimp's canines. "It's just a treasure trove of surprises," says C. Owen Lovejoy, one of the leaders of the team and an anthropologist at Kent State University. Take the small canines (teeth), he says. A chimp's big, protruding canines — especially the males' — are for fighting or intimidating other males to get access to females, Lovejoy says. Small canines on Ardipithicus suggest a different social strategy. "So females are picking males that are using some other technique to obtain reproductive success, and that technique is probably exchanging food [to have children]," Lovejoy says. The cover of Science showing the partial skeleton of Ardipithecus ramidus, a hominid species living about 4.4 million years ago in Ethiopia. T. White White and Lovejoy say that the hand and arm bones, as well as bones from the feet and pelvis, suggest that Ardi was able to walk on two legs. But it was probably more comfortable in the trees, though it maneuvered on its palms in a way different from chimps. The team spent almost two decades collecting everything from animal bones to pollen in the region. They conclude that Ardi lived in a lush, wooded environment, not the grassy savanna usually thought to be the habitat of the earliest human ancestors. "This is more important than Lucy," says anthropologist Alan Walker of Penn State University. The number of bones and its greater antiquity (age) give scientists a wealth of new information on this earliest part of human evolution. At the same time, he says, the team's conclusions will draw a lot of skepticism from other scientists. Among the skeptics is Bernard Wood, professor of anatomy at George Washington University. Wood says it could well be that these bones belonged to a creature that evolved outside the line that led to humans — that it was in fact a separate branch of primate evolution that disappeared into a dead end, like so many other forms of ancient life. The scientific community will now get a chance to test the team's conclusions, which are outlined in 11 papers — with 47 authors — in the journal Science.