2.3.1 Consonants of Atsam

ASPECTS OF PHONOLOGY

OF ATSAM LANGUAGE

AYANDIPO OMOTOLA ISLAMIYAT

07/15CB040

A LONG ESSAY SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF

THE REQUIRMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF A DEGREE OF

BACHELOR OF ARTS IN LINGUISTICS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF

LINGUISTICS AND NIGERIAN LANGUAGES, UNIVERSITY OF

ILORIN, ILORIN, KWARA STATE, NIGERIA.

JUNE, 2011

i

CERTIFICATION

The undersigned certify that this project report prepared by AYANDIPO

OMOTOLA ISLAMIYAT (07/15CB040), titled

“ASPECTS OF PHONOLOGY IN

ATSAM LANGUAGE’’ meets the requirements of the Department of Linguistics And

Nigerian Languages, University of Ilorin, for the award of the Bachelor of Arts degree.

B. A (HONS) in Linguistics.

------------------------------

MR. WALE K. RAFIU

(Supervisor)

------------------------------------

PROF. ABDUSSALAM

Head of Department

-----------------------------------

EXTERNAL EXAMINER

--------------------------

DATE

--------------------------

DATE

---------------------------

DATE ii

DEDICATION

This report is dedicated to Almighty God who gave me the power and strength to complete this report.

Also to my parents, Engr. & Mrs. Ayandipo and my siblings who have been very supportive in my educational pursuit.

iii

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I’m very grateful to Allah for his grace and protection. I am also very grateful for the opportunity given to me to learn in this noble school of ours. My sincere gratitude goes to Engr. & Mrs Ayandipo, Mr. K. Rafiu,

Mrs. J. Oke, Onaolapo Najeeb, Ayo Dada and all others who helped to make this project a success.

iv

TABLE OF CNTENTS

Title page

Certification

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Table of contents

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

1.1 Introduction

i

ii

iii

iv

v

1

1.2

Historical Background: 2

1.2.2 Population Structure and Distribution 3

1.2.3 Urban and Rural Development and Patterns of Human Settlement 4

1.3 Geographical Background of the study area. 5

1.4 Socio-Cultural Profile:

1.8 Theoretical framework

1.5 Genetic Classification of the Atsam Language

1.6 Scope and Organisation of the Study

1.7 Aim of the study

9

10

13

14

14 v

1.9 Methodology 15

1.10 Data collection and Data Analysis

1.10.1 Review Of The Chosen Frame Work

1.10.2 The Structure Of The Generative Phonology

1.10.2.1 Underlying Representation

1.10.2.2 Phonological Rules

1.10.2.3 Surface Representation

15

17

17

19

19

19

CHAPTER TWO: BASIC PHONOLOGICAL CONCEPTS

2.1 Introduction 21

2.2 Phonology defined

2.2.1 Phonemes and Allophones

2.3 The Sound Inventory of Atsam

21

22

23

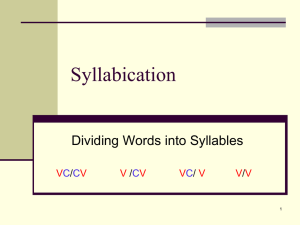

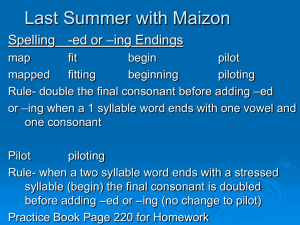

2.3.1 Consonants of Atsam 23

2.3.1.1 The description and distribution of the consonants of Atsam 24

2.3.2 Vowels of Atsam 33

2.3.2.1 The description and distribution of Atsam vowels 33 vi

2.4 Tone inventory of Atsam

2.5 Syllable Inventory of Atsam

2.6 Distinctive features

2.6.1 Justification of the Features Used

37

39

42

44

2.6.2 Justification of the Features Used 45

CHAPTER THREE: PHONOLOGICAL PROCESSES IN ATSAM

3.1 Introduction 47

3.2 Phonological processes defined

3.2.1 Assimilation/assimilatory processes

3.2.1.1 Nasalization

3.2.1.2 Labialization

3.2.1.3 Palatalization

3.2.2 Deletion

3.2.3 Insertion

47

48

49

51

53

54

55 vii

CHAPTER FOUR: ATSAM TONOLOGICAL AND SYLLABLE

PROCESSES

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Defining a tone language

58

58

4.2.1 Atsam tone typology

4.2.2 Co-occurrence of tones in Atsam

4.2.3 Function of tones in Atsam

4.2.4 Tonological Processes

4.2.4.1 Tone Spreading

4.2.4.2 Tone Stability

4.2.4.3 Tone Floating

4.3 The Syllable Structure of Atsam

4.3.1 Syllable Typology in Atsam

4.3.2 Syllable Structure in Atsam

59

59

64

66

66

62

63

64

64

64

CHAPTER FIVE: SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Summary viii

70

70

5.3 Findings/Observations

5.4 Recommendation

5.5 Conclusion

71

71

72

CHAPTER ONE

1.1 General Introduction

INTRODUCTION

Language can be defined in so many ways as there are many scholars in the study of language who have looked into it in different ways. It is a known fact that every human on earth knows at least one language, spoken or signed which has given rise to the need to study and understand these languages.

Linguistics, therefore, has been defined as the science of language, including the sounds, words, and grammar rules. It should be noted that words in languages are finite because they are primarily what make up sentences, but sentences are not finite. It is this creative aspect of human language (i.e. the ability of man to use words to create sentences) that sets it apart from animal language, which is essentially responses to stimuli (Fromkin & Rodman undated).The rules of a language, also called grammar, are learned as one acquires a language. These rules include phonology , the sound system which is our area of emphasis, morphology , the structure of words, syntax , the combination of words into sentences, semantics , the way in which sounds and meanings are related, and the lexicon , or mental dictionary of words. ix

There are no less than 5,000 languages (probably a few more thousands) in the world right now and linguists have discovered that these languages are more alike than different from each other. There are universal concepts and properties that are shared by all languages and these principles are contained in the

Universal Grammar , which forms the basis of all possible human languages.

Nigeria is the most complex country in Africa, linguistically, and one of the most complex in the world. Crozier & Blench (1992) comment on this confusion as being basically about status and nomenclature which remains rife with inaccessibility of many minority languages is an obstacle to research. There are about 521 languages in Nigeria today which have been estimated and catalogued.

This number includes 510 living languages, two (2) second languages without native speakers and nine (9) extinct languages. In some areas of Nigeria, ethnic groups speak more than one language. The major languages spoken in Nigeria represent three major families of African languages – that is the Niger-Congo languages, Afro-Asiatic and the Nilo-Saharan .

There are 57 languages spoken as first languages in Kaduna State. Gbari and

Hausa are major languages; most other languages are small and endangered minority languages, due to the influence of Hausa. The language of study Atsam is a language spoken by the Atsam people of southern Kaduna specifically in

Kauru LGA, Kaduna State.

1.3

Historical Background

Kaduna State forms a portion of the country's cultural diversity because representatives of the six major ethnic groups in the country are found in the x

state. Apart from this fact, there are also present over twenty other ethnic minority groups, each with its language and art or religion different from the other.

The works of art and pottery (e.g. the "Nok Terracotta") found in the southern parts of Kaduna State suggest that it is a major cultural centre. Among the major ethnic groups are Kamuku, Gwari, Kadara in the west, Hausa and

Kurama to the north and Northeast. "Nerzit" is now used to describe the Jaba,

Kaje, Koro, Kamanton, Kataf, Morwa and Chawai (study group) instead of the derogatory term "southern Zaria people". Also, the term "Hausawa" is used to describe the people of Igabi, ikara, Giwa and Makarti LGAs, which include a large proportion of rural dwellers who are strictly "Maguzawas."

In the north, the Hausa and some immigrants from the southern states practise Islam and majority of the people in the southern LGAs profess

Christianity. The major Muslim festivals are the "Salah" celebrations of

"ldeIfitri" and "ldeIkabir", while Christmas, New Year and Easter are observed by the Christians. Two traditional festivals of significance are the "Tukham" and

"Afan" in Jaba and Jama'a LGAs respectively. Prominent among the traditional arts, are leather works, pottery and in-dig-pit dyeing with Zaria as the major centre.

1.2.2 Population Structure and Distribution: The 2006 census provisional result puts the population of Kaduna State at 6 ,066,562. Although majorities live xi

and depend on the rural areas, about a third of the state's population is located in the two major urban centres of Kaduna and Zaria.

However, except in the northwestern quadrant, the rural population concentration is moderate, reaching a hight of over 500 persons per sq. km. in

Kaduna/Zaria and the neighbouring villages 350 in Jaba, Igabi and Giwa and 200 in Ikara LGAs. Despite the provisional nature of the census results, observations of movements of young able bodied male labourers in large numbers, from rural villages to towns during the dry season and back to rural agriculture fields during the wet season, suggest a sizeable seasonal labour force migration in the state.

The seasonal labour migration has no effect on agricultural labour demands in the rural traditional setting. Indeed, some of these seasonal migrants come to town to learn specific trade or acquire special training and eventually go back to establish in the rural areas as skilled workers (e.g. masons, technicians, tractor drivers, carpenters, motor mechanics, etc). Another major feature of the

State's population structure is the near 1:1 male/female ratio, not just for the state as a whole, but even in all the LGAs.

The effects of this may be helpful to the future social and economic development of the rural sector especially in the agro-allied rural industries. The large number of secondary school leavers, polytechnic and university graduates provides a growing skilled labour force for the growing industries in the state.

1.2.3 Urban and Rural Development and Patterns of Human Settlement:

The pattern of human settlement throughout the state is tied to the historical, political and socioeconomic forces the area has been subjected to, from the prexii

colonial to post colonial period. Prior to the advent of the British occupation, the basic unit of human settlement was the extended family compound.

As compounds grew, the needs for security and defence led to a higher hierarchy of settlements called "Garuruka" (towns). These towns were protected by walls with a titled/administrative head appointed by higher political authority, the "Sarki". This pattern of settlement dominated the Hausawa cultural groups to the north (i.e. Giwa, Igabi, Zaria, Sabon Gari, Kudan, Makarfi and parts of lkara

LGAs).

Higher settlement hierarchy than the rural extended family compounds in other parts of the state was delayed, until the development of social amenities and infrastructure such as motor and rail road, Christian Missionary establishments and recently, produce buyers, markets and administrative reorganizations gave impetus (settlements such as Birnin Gwari, Kuda'a, Kachia,

Zango Kataf, KwoiSambam Kagoma and Saminaka are good examples). It is the impact of these historical and cultural developments on settlement pattern and probably because of the nature of the rural economy (agrarian) that created the dominance of the two urban centres (i.e. Zaria and Kaduna) in the state.

1.3 Geographical Background of the study area.

The study area is Kauru Local Government Area of Kaduna State of

Nigeria. The state is the successor to the old Northern Region of Nigeria, which had its capital at Kaduna. In 1967 this was split up into six states, one of which was the North-Central State, whose name was changed to Kaduna State in 1976.

This was further divided in 1987, losing the area now part of Katsina State . xiii

Under the governance of Kaduna State is the ancient city of Zaria . Kaduna State is located between longitude 10 0 31’23’’North and 7 0 26’25’’ east. And the capital is Kaduna city. Figure 1 shows the location of Kaduna State on the map of

Nigeria. xiv

Fig 1

Map of Nigeria showing Kaduna State. (Source: File:Nigeria location map.svg)

There are two marked seasons in the State, the Dry windy season and the

Rainy (wet) Seasons. The wet season is usually from April through October with great variations as you move northwards. On the average, the state enjoys a rainy season of about five (5) months. There is heavy rainfall in the southern parts of the state like Kafanchan and northern parts like in Zaria with an average rainfall of about 1016mm. Kaduna State extends from the tropical grassland known as Guinea Savannah to the Sudan Savannah in the North. The grassland is a vast region covering the southern part of the state to about Latitude 1100’’

North of the equator. The prevailing vegetation of tall grass and big trees are of economic importance during both the wet and dry seasons.

The state is divided into 23 Local Government Areas. Kauru is one of the

23 Local Government Area s of Kaduna State with its headquarters in Kauru.

Kauru Local government has an area of 2,810 km² and a population of 170,008

(2006 census). See Fig 2. (Map xv

of Kaduna state showing senatorial districts)

Fig 2 Map of Kaduna State showing senatorial districts and local Government

Areas (Source: www.kadunastate.org.ng) xvi

Latitude, Longitude, and Elevation

Kauru local government of Kaduna State is located at

9°52'11"N latitude and

7°57'35"E

longitude and an average elevation of 706 meters.

Timezone

The time zone for Kachia is Africa/Lagos.

1.4 Socio-Cultural Profile:

The following could be observed among the Atsams. The language Atsam is seen as a means of communication in the market and also used for worshiping at the church. The atsam language is spoken in towns like Pari, Kizachi, Makama,

Chawai, Rahama Chawai etc. the speakers of this language that is the atsam/chawai are known for the preservation of their culture despite much influence and threat from the western world. For instance, among these people, a child is not allowed to greet an elderly person in the western manner or way.

The Atsam people are known to be hospitable, helpful, industrious and peace loving. When one knocks on the door of and Atsam/Chawai person at any hour of the day, one is assured of a warm welcome. This is why they are usually regarded as the most peace loving people of Kaduna State. Another aspect of their culture is their ability to be able to dance. This has been passed down from generation to generation. They are very good dancers and in fact they are the best in the whole of Kaduna State.

The Atsam people are predominantly farmers i.e. about 80% of the population though there are few who engage in other income generating xvii

ventures. Among the crops of cultural importance is the finger Millet popularly known as ‘tamba’, ‘acha’ or just millet. Just few of them engage in trading, fishing, craft making and bee keeping which also are income generating ventures for the community. Religion is a vital part of life of the people and to this end; there are two major religions in the chiefdom namely Christianity and Islam.

However, some atsam people are adherents of traditional religion popularly called ‘dodo’.

Among the people of Atsam, the marriage institution is contracted in stages such as: step I is when the dowry is paid and then followed by the second step which is the marriage ceremony proper. On the wedding day, the groom presents gift items like palm oil, groundnut oil, ram etc to the bride’s family after which he is permitted to take his bride home. Names are given to children on the very day they are born but celebrations are postponed to the convenience of the parents.

1.5 Genetic Classification of the Atsam Language:

The people of Southern Kaduna are also referred to as Nerzit . While they speak many different languages and see themselves as separate peoples, their unity as a group is also quite apparent to them. Hausa, an Afro-Asiatic, Chadic language, is the lingua franca of Northern Nigeria, and this holds true all over

Kaduna State where over 57 languages are spoken. Benue-Congo languages, particularly those of the Plateau variety, are the mother tongues spoken by the indigenes. Of these, some of the languages are as mentioned below: Fantsuam

(Kafanchan), Gong (Kagoma), Gworok (Kagoro), Hyam (Jaba), Jju (Kaje), Koro,

Tsam (Chawai) the study language and Tyap (Kataf). xviii

There is lack of sufficient data as regards the study language all because the languages of Southern Kaduna are undoubtedly minority languages and as such, understudied. Minority because they are each estimated to have fewer than one million native speakers. They are also considered to be endangered because of pressure from Hausa which for long has been the lingua franca in the north of the country. However locally, these languages remain in use.

According to Blench (1992:94), Atsam belongs to the Platoid group found under the Benue-Congo sub family of the Niger-Congo shown in family/phylum.

This is the tree structure (fig 3) below. xix

Afroasiatic

African Languages

Niger

Kordofanian

Nilo saharan Khoisan

Niger-Congo

Kru Gur Adamawa eastern

Kordofanian

West Atlantic

Fatsuan

Platoid

Gong Atsam

Benue-

Congo

Yoruboid

Koro

Bantoid

Tyap Ijuu

Fig. 3 The Tree diagram showing the genetic classification of

Atsam Language (Blench 1992:94) xx

1.6 Scope and Organisation of the Study

The whole of the Atsam language as in how the words are used in the construction of sentences is in review. However, till date, no linguistic research has been undertaken on Atsam language in general and the influence of Hausa language on the study language in particular. As Atsam might be facing gradual death, linguistic research on Atsam becomes inevitable.

This thesis is divided into four chapters. The first chapter gives the general background to the study. This chapter also provides information on the socio-cultural profile of the Atsam speakers, genetic classification of the language under study and the methodology adopted for the study.

Chapter two discusses the basic phonological concepts of Atsam. We also examine the consonant and vowel inventories of the language. An adept study of the syllable structure of Atsam is presented.

In chapter three, we look at the interaction of sounds both within and across words or phrases. Phonological and syllable structure processes like assimilation, deletion and insertion are discussed with data from Atsam.

The last chapter deals with discussion as it gives an overview of the language. It also takes into consideration the ecological models of Haugen (1972) and Edwards (1992) to understand the status of this minority language. It also gives further findings, summary and conclusion of the study. xxi

1.7

Aim of the study

The aim of this study is to discover the sounds that are attested in Atsam language. It is also our view to examine the status of these sounds with respect to their use in the language. Also, the interaction of these segments and how they are used to arrive at meaningful utterances also. All these will be done so as to make a significant linguistic generalization on the language.

A second aspect we shall be considering is the set of rules which specify exactly how each sound of the words are pronounced and how these sounds affect and are affected by the sounds around them. This aspect is important for learning the language.

1.8 Theoretical framework:

Noam Chomsky and Morris Halle propoounded the Generative School of

Phonology in the late 1950's. Its basic premises are that phonological structure reflects the linguistic competence of the individual native speaker to compute a phonetic representation for the potentially infinite number of sentences generated by the syntactic component of grammar and that this competence can be investigated in a serious scientific fashion. The generative point of view has become dominant in the field of linguistics and has had varying degrees of influence on other cognitive sciences (Kenstowicz undated).

In several ways, the development of generative phonology (and generative grammar more generally) was born of a disciplinary rupture, and brought with it rifts in the field. Proponents of generative grammar (ironically, in light of the similar views of the earlier generation of linguists noted above) believed that xxii

generative grammar was the first truly scientific account of language, the first to develop something that could be called a theory (Goldsmith & Laks undated).

1.9 Methodology

This section discusses the methods that will be used for this study. Atsam, does not have a script. So the only source of data was primary data collected by intensive field work. For the descriptive part, a questionnaire based on the 400 word list was used. The speakers were from Lagos and Ibadan so that the representative and comparison sample of the study language could be achieved.

Also recording is by involving the informants (speaker) emotionally so that they stopped being conscious. The data will then be analysed, in view of the theoretical perspectives on minority language and the various socio-linguistic ecological parameters stated in the section above.

The following methods were used to acquire data for the study:

Key-informant Interview

Structured interviews.

Key-informant Interview: the informants are usually people who have a good knowledge of the language in question and wishes to talk. One of the easiest ways to find an informant is to engage in general discussion with the members of the community and or the speakers of the language of study so as to determine if the person(s) has a good enough knowledge. Another way is to use one key informant to locate another one. In the case of this study, adult native speakers of atsam were engaged. xxiii

Structured Interviews:

This entails administration of well formed questions which have the same meaning to the interviewer and respondent. The main aim for this was to acquire as much information on the language and peopleas possible.

1.10 Data collection and Data Analysis:

Since words of the study language were primarily used in this work, then we shall explain the premises under which data were collected.

The first premise is that Linguistics is a descriptive rather than a prescriptive discipline and as such, the objective is to describe the systematic nature of the language as used by the members of the particular speech communities rather than to pass (prescriptive) judgments about how well they speak or how they should or should not be using their language.

A second related premise is that every naturally used language variety is systematic, with regular rules and restrictions at the lexical, phonological and grammatical level (Rickford 2002).

The third premise of linguistics which we think is important is that in trying to understand and describe the system of a language as the case is in the study of the Atsam language, primary attention should be given to speech rather than writing. The main reason for emphasizing this is that the written language omits valuable information about the pronunciation or sound system of a language. xxiv

The fourth and final premise is that although languages are always systematic variation among their speakers is absolutely normal.

1.10.1 Review of the chosen frame work

As stated earlier, the appropriate theoretical framework chosen for this long essay is generative phonology propounded by Noam Chomsky and Morris

Halle in their book, “The sound pattern of English” published in 1968.

Generative phonology constitutes part of the linguistic theory which is called

“Transformational generative grammar (T.G)” formulated by Chomsky (1957) in order to address the inadequacies in the discovery procedure of the classical taxonomic phonemics. Goldsmith (1995:25) states that, the theory of generative phonology proposed by Chomsky and Halle in “The Sound Pattern of English”

(1968, henceforth SPE) made a radical departure from classical phonemics.

Hyman (1975) describes generative phonology as the description of how phonological rules can convert the phonological representation into phonetic representation and to capture the distinctive sounds in contrast in a language. In essence, the main idea behind the theory of generative phonology is in the discovery of phonological rules that will map phonological representation on phonetic or surface representation (Oyebade, 1998). This explains why generative phonology is often considered as a phonological theory that is ruledbased.

1.10.2 The Structure of Generative Phonology

Generative phonology has a structure and this was postulated by the major proponents of the theory (Chomsky and Halle). Hyman (1975:80) submits that Chomsky and Halle propose that highly abstract systematic phonetic xxv

representations be postulated; from which rules derive the various surface realizations. Likewise, Oyebade (2008:12) observes that generative phonology assumes three very crucial components: the underlying representation, the phonetic representation and the rules which link the two together. In his own scholarly submission, Goldsmith (1995:26) says that classical generative phonology is deeply entrenched in the metaphor of grammar in which as a production system that gives rise to a conception of grammar in which modules as well as principle are typically stated as a rule, that is, a procedure that takes a level of representation as well: a module with its set of principles takes a level of representation as the output. Between these two levels of representation defined by the grammar is an intermediate stage in the derivation of output from the input.

Thus, the input level of phonological representation is the abstract phonemic representation, which is the basis for any derivation, the output level of phonological representation is the surface phonetic level. The intermediate level, therefore, is the phonological rule that derives the output level of representation

(i.e the surface phonetic level) from the input level of representation (i.e the phonetic level). This can be illustrated formally below:

Phonetic representation (surface form)

Phonological rule (intermediate level)

Phonemic representation

(underlying form) xxvi

1.10.2.1 Underlying Representation

Underlying representation is an abstract representation existing in the linguistic competence of the native speaker. At this level, items with invariant meaning have identical realization (Oyebade, 2008:12). Also, Schane (1973) opines that underlying representation is a level in which alternants are represented identically. In their own view, Gusssenhoven and Jacobs (1998:48) claim that the underlying form expresses the phonological unity of the morpheme’s variants. Thus, the underlying is a non-predictable form which serves as the base from which the surface level (i.e. variants) is derived with the aid of phonological rules.

1.10.2.2 Phonological Rules

Oyebade (2008:15) claims that, “phonological rules are directives which map underlying forms on surface forms”. He stresses further that these rules show the derivational sequence or path of an item in its journey from the underlying level to the phonetic level. In a similar vein, Botha (1971:60-61) describes phonological rules as rules of the phonological component of a grammar which constitute the formalized representations of the phonological processes of a language. These rules apply to phonological surface structures, deriving from them those aspects of phonetic representations of a language. In essence, phonological rules apply to underlying representations and convert them to other representations (Schane, 1973:93).

1.10.2.3 Surface Representation

Kenstowicz cited in Oyebade (2008:20), says that the phonetic representation, otherwise called surface representation, indicates “how the lexical xxvii

item is to be realized in speech”. Schane (1973) states that, it is the derived representations which directly tell us the different phonetic manifestations of a morpheme. The surface phonetic representation is predictable as a result of the fact that the pronunciation of segments varies with the phonological contexts in which they occur. On this premise, it is obvious that the phonetic representation is similar to what is realized in actual speech; and it is the level of representation derived from the underlying level by the application of phonological rules. xxviii

CHAPTER TWO

BASIC PHONOLOGICAL CONCEPTS

2.1 Introduction

In this chapter, we shall examine some basic phonological concepts in

Atsam language which are sound inventory, tone inventory and syllable inventory. Also, we shall investigate how the speech sounds of Atsam are distributed, and the distinctive features matrix of the sounds shall be presented.

2.2 Phonology defined

According to Hyman (1975:2), “phonology has been defined as the study of sound systems, that is, the study of how speech sounds structure and function in languages”. It is the task of phonology to study which differences in sounds are related to differences in meaning in a given language (Trubetzkoy, 1939:10).

Also, Katamba (1989:1) considers phonology as the branch of linguistics which investigates the ways in which sounds are used systemically in different languages to form words and utterances. In his own contribution, Oyebade

(2008:2) defines phonology as the scientific study of the arbitrary vocal symbols used in human speech and the patterns into which these symbols enter to produce intelligent, meaningful utterances.

From the various submissions on phonology given above, it can be deduced that phonology essentially centres on how sounds of a language can be combined to form meaningful words, and this combination of sounds is checkmated or governed by what is known as the “phonotactics” of a language.

That is, the rules governing the permissible and non-permissible sound sequence. xxix

Phonology branches into segmental and autosegmental. The segmental phonology is restricted to the level of sound segments e.g. vowels and consonants while the auto/supra segmental phonology deals with the level above the segments. That is, the phonetic features of speech such as tone, stress, length, intonation, e.t.c.

2.2.1 Phonemes and Allophones

Phoneme is the fundamental unit of phonology. It can be defined as a family of sounds in a given language which are related in character and are used in such a way that no member ever occurs in a word in the same context as any other member (Jones, 1948). A phoneme is the minimal phonology unit that is capable of contrasting word meaning. Along this view, Yule (1985) asserts that,

“the essential property of a phoneme is that it functions contrastively”. On the other hand, allophones are a set of phones that are derived from a phoneme. They are context-dependent variants. It should be added that allophones vary with respect to contexts in which they occur such that where one occurs, the other is not found; but are usually considered as the different phonetic manifestations of a single phoneme in different phonetic contexts.

As it is known that the primary task of phonology is to discover the status of a phoneme, the principles or procedures commonly used in testing for phoneme are: Minimal pair, Complementary distribution, Analogous environment and Free variation. xxx

2.3 The Sound Inventory of Atsam

Every natural human language has its own sound inventory. By sound inventory, we mean the sounds that are attested in a given language. These sounds are grouped into two, Consonants and vowels. Atsam language is not an exception to the rule, in that it attests both consonants and vowels in its sound inventory. Atsam attests forty sounds, twenty seven consonants and thirteen vowels.

2.3.1 Consonants of Atsam

Schane (1973:9) views consonants, with their various degrees of constriction, as constituting more closed phases, where the outgoing air is impeded. Along this perspective, a consonant is a sound that is produced with a partial or total obstruction of the airstream in the vocal tract. Three articulatory parameters are often used in describing consonants, these are: place of articulation, manner of articulation and state of the glottis. In Atsam language, twenty seven consonant sounds are attested. These consonants are presented in a chart form below: xxxi

Atsam Phonemic Consonant Chart

Stop p b t d k g kp gb

Fricative

Affricate

Nasal

Lateral

Flap

Approximant

m f v s z ∫ ts t∫ n l r j w

2.3.1.1 The description and distribution of the consonants of Atsam. k w g w h

[p] Voiceless bilabial stop occurs at

Word initial: [p s] “vomit”

[pãzìm] ‘new’

[pì](belly)]

Word medial :[g w apjәn] ‘spear’

[timp n] ‘wall’ xxxii

[ápặkor] ‘wing’

Word final: [vә / p] ‘lizard’

[ùrәp] ‘guinea fowl’

[kúp] ‘bone’

[b] Voiced bilabial stop occurs at

Word initial: [bét∫í]

‘hair’

[búb]

‘oil’

[barad]

‘skin’

Word medial: [tabâa]

‘tobacco’

[bubsãt]

‘oil palm’

[ìb b ]

‘dawn’

Word final: [sәnab]

‘air’

[bub]

‘oil’

[t] Voiceless Alveolar stop occurs at

Word Initial: [tám]

[takilími]

'chin'

'shoe'

[timp k]

Word medial: [t ítak]

[pátãjã]

'wall'

'thigh'

'hoe' xxxiii

[mutárag] 'door' word final: [jelt] "wine/beer"

[rùwũt]

[jút]

"dry season"

"darkness"

[d] Voiced Alveolar stop occurs at

Word initial: [dũ] "mortar"

[dòdó] "fetish"

[dàmi] “hold”

[ dòdó] “fetish”

[ kúruní ád m ] “nineteen (19)”

[ g w ãdi ] “friend”

Word final: [jébéd] “toad”

[ ád ] “build”

[ àd ] “play”

[k] Voiceless velar stop occurs at

Word initial: [ kùd ]

“return”

[ kũkũ ]

“kneel”

[ k kĩ ]

“dry”

Word medial: [wɔkrì]

“right”

[ ĩká ]

“mother”

[ sùrùkí ]

“in- law”

Word final: [ kúrunata:k ] “thirteen”

[ jũk ]

“mosquito”

[ ĩgùlúk ]

“vulture”

[g] Voiced velar stop occurs at

Word initial: [ gõzĩ ]

“he goat” xxxiv

[gàdà] “groundnut”

[góró]

“kolanut”

Word medial: [k w áràgata] “louse”

[nágítʃe] “buffalo”

[námgítʃe] “animal”

Word final: [waŋg] “crocodile”

[ʃisãg] “sand”

[bĩg] “word”

[k^p] Voiceless labial- velar stop occurs at

Word initial: [kpàrí] “fry”

[kpàgì] “grind”

[kpárkí] “soak”

Word medial: [gíkpar] “strong”

[ykpakpas] “heavy”

[gb] Voiced labial -velar stop occurs at

Word initial: [gbãjĩ] “roast”

[gbãì] “burn”

[gbag] “jaw”

Word medial: [íngbãsai] “old person”

[digbar] “hard”

[pãgbargì] “grinding stone”

[k w

] Voiceless labialized velar stop occurs at

Word initial: [k w ak] “hawk”

[k w áràgata] “louse”

[k w ùk]

“go” xxxv

Word medial [kuk w ar] “snail”

[g w ]Voiced labialized velar stop occurs at

Word initial: [g w apjan] “spear”

[g w ap]

[g w ãzì]

“bow (weapon)”

“crab”

Word medial: [ag w ag w a] “duck”

[f] Voiceless labio-dental fricative occurs at

Word initial: [fàtàràg] “reply”

[fítírí]

[fòĩ]

“turn”

“sweet”

Word medial: [rife:t]

[pũfu]

[náfìd]

“tail” “rubbish heap”

“buttocks”

[v] Voiced labio-dental fricative occurs at

Word initial: [vú:m] “fight”

[vɔrì] “plait”

[víyĩ]

Word medial: [rívɔrì]

“beat”

“rainy season”

[ìvã] “big”

[s] voiceless Alveolar fricative occurs at

Word initial: [sōmu] “beans”

[sas]

[sã:g]

“that”

“basket”

Word medial: [bubsãt] “oil palm”

[kàsuwá] “market”

[ʃisãg] “sand” xxxvi

Word final: [abáss]

[rias]

“urine”

“man”

[hu:sus] “wife”

[z] Voiced Alveolar fricative occurs at

Word initial: [zã]

[zí]

[zԑ]

Word medial: [àzĩmát]

[wùzì]

[gãzì]

Word final: [ráiź]

“put”

“guest”

“give birth”

“fall”

“divide”

“chief”

[ʃ] Voiceless palato -Alveolar fricative occurs at

Word initial: [ʃárì]

[ʃisãg]

[ʃuni]

Word medial: [kúrʃadɔm]

[a ʃai]

[ʃú ʃɔ]

“choose”

“sand”

“thing”

“nineteen”

“full”

“sit”

[h] Voiceless glottal fricative occurs at

Word initial: [húsúz]

“wife”

[hwur]

[hu:sus]

Word medial: [rháh]

[jéhí]

Word final: [táh]

“navel”

“wife”

“house”

“weep (cry)”

“shoot” xxxvii

[ts] Voiceless Alveolar affricate occurs at

Word initial: [tsatsa]

[titsí]

[tsírí]

“charcoal”

“push”

“needle”

Word medial: [tsãamítsãsus ]

“sister younger”

[gùtsímã]

“pass(by)”

[tĩtsibaràk]

“skin”

[t ʃ] Voiceless Palato Alveolar Affricate

Word initial: [tʃítʃì]

“saliva”

[tʃì]

[tʃià]

Word medial: [zútʃia]

[jetʃaa]

[nágitʃe]

“fish”

“work”

“heart”

“bush”

“buffalo”

[ʤ] Voiced Palato -Alveolar occurs at

Word initial: [ʤá:]

[ʤàrkí]

Word medial: [kaikuʤὲ]

[ríʤìá]

“elephant”

“donkey”

“old”

“well”

[m] Voiced Bilabial Nasal occurs at

Word initial: [mutarag]

[muzì]

[máràk]

Word medial: [timpɔk]

[jémbú]

[námgitʃe]

“door”

“seed”

“thing”

“wall”

“mud”

“animal” xxxviii

Word final: [ʃàm]

[tsãzizàm]

[atʃirim]

“song”

“male”

“six”

[n] Voiced Alveolar Nasal occurs at

Word initial: [nízìgĩ]

[nám]

[núkjãk]

Word medial: [anasi]

[g w andi]

[ìjang]

Word final: [tsan]

[aman]

[pan]

“surpass”

“meat”

“water pot”

“four”

“friend”

“lick”

“son”

“money”

“moon”

[ ] Voiced Palatal Nasal occurs at

Word initial: [ túk]

“right”

Word medial: [ja k]

[rùwu t]

[jɔ k]

“fire”

“dry season”

“horn”

[ŋ] Voiced Velar Nasal occurs at

Word medial: [tɔŋg] “ear”

[rehaŋg]

“remember”

[l] Voiced Alveolar Lateral occurs at

Word initial: [lám]

“tongue”

Word medial: [kolԑkolԑ]

[ĩgùlúk]

“boat”

“vulture” xxxix

Word final: [áwúrúl]

“eight”

[r] Voiced Alveolar Flap occurs at

Word initial: [rík]

[rívɔrì]

[rírɛk]

Word medial: [dara]

[jãrĩ]

[barad]

Word final: [mar]

[wɔr]

[jãír]

“rope”

“rainy season”

“story”

“guinea corn”

“food”

“skin”

“back”

“hand”

“star”

[j] Voiced Palatal Approximant occurs at

Word initial: [jémbú]

[jébéd]

[jú:]

Word medial: [rìjĩ]

[tsãjã]

[bajɔrɛk]

“mud”

“toad”

“thief”

“ground”

“bird”

“bad”

[w] Voiced Labial Velar Approximant occur at

Word initial: [wɔkrì]

“right”

[wãg]

[wùẽ]

Word medial: [ĩwút]

[àwúrú]

[tɔwá]

“swallow”

“dance”

“forget”

“loose”

“throw” xl

2.3.2 Vowels of Atsam

Schane (1973:9) views vowels as constituting open stages where the outgoing air flows freely. That is, vowels are sounds that are made with little or no obstruction of the airstream in the vocal tract. In Atsam language, thirteen vowels are attested, there are eight oral vowels (one long and seven short) and five nasal vowels. These vowels are represented in the following charts:

2.3.2.1 The description and distribution of Atsam vowels.

Front Central Back high i u close

o half close

ɔ half open mid high e mid low ɛ low a:

Table1 The Oral vowel chart of Atsam xli

Front Central Back high ĩ ũ close mid low low

ε

ã

ɔ half open

open

Table 2 The Nasal Vowel Chart of Atsam

Vowel sounds

[i] Front high unrounded vowel

Word initial: [ĩgbăsai] ‘old person’

[ĩbă] ‘father’

[ĩdong] ‘one’

Word medial:[jĩgĩtor] ‘delecate.

[jis] ‘eye’

[t∫i] ‘head’

Word final: [pi] ‘belly’

[bétʃí] ‘hair’

[tʃì] ‘fish’

[u] back High rounded vowels

Word medial: [tsãsusɔ]

‘dauther’ xlii

[kúrãásí]

‘forty’

[kúdε]

‘return’

Word final; [jú:]

‘thief’

[awuru]

‘eight’

[ʃú]

‘drink’

[e] Front mid high unrounded vowel

Word medial; [jéhí]

‘cry’

[wuẽ]

‘dance’

[pèrák]

‘gather’

Word final: [jè:]

[ré:]

‘come’

‘rain’

[námgítʃe] ‘animal’

[ε] Front mid low unrounded vowel

Word medial: [wεi]

[bεrà]

‘day’

‘bocklor’

[g w εrì] ‘fly’

Word medial: [kudε] ‘return’

[k∫ówjε] ‘village’

[t∫iε] ‘farm’

[o] back mid High rounded vowel

Word medial: [gõzi]

[dòdó]

[góró]

‘he goat’

‘fetish’

‘kolanut’

[ ɔ] short mid low back rounded vowel occurs at

Word medial : [zɔm]

‘fat’ xliii

[pɔk]

[kɔ]

‘ room’

‘war’

Word final: [t∫ĩjεwɔ] ‘arm’

[wɔrɔ] ‘calabash’

[a] Back low unrounded vowel

Word initial: [ag w ag w a]

‘duck’

[ata:k]

‘three’

[atuw ]

Word medial: [∫àm]

[máràk]

‘five’

‘song’

‘ thing’

[jәsi]

Word final: [kúrá]

‘fear’

‘dust’

[kàsuwá]

‘market’

[nwá]

‘mountain’

[ĩ] Front unrounded nasalized vowel

Word initial: [ĩká]

[ĩbá]

‘mother’

‘father’

[ĩdong] ‘one’

Word medial: [at∫ĩrim] ‘six’

[∫ĩtí]

‘cold’

[k k ĩ] ‘dry’

[ ũ] Back rounded nasalized vowel

Word medial: [kũt∫ú]

‘neck’

[b ũmí]

‘palm wine’

[pũfu]

Word final: [jũ]

‘rubbish heap’

‘mouth’ xliv

[wũ]

[rũ]

‘nose’

‘knee’

[ ε] mid low front unrounded nasalized vowel

Word final:[ pε] ‘soon’

[ɔ] Back mid low rounded nasalized vowel

Word final: [ adɔ ]

‘nine’

[atuwɔ ]

[wɔrɔ]

‘five’

‘calabash’

2.4 Tone inventory of Atsam

Tone is one of the prosodic features of speech and it is undertaken in auto segmental phonology. Tone languages are languages that have “lexically significant, contrastive but relative pitch on each syllable”. In his own perspective, Welmers (1959:2) proposes that “a tone language is a language in which both pitch phonemes and segmental phonemes enter into the composition of at least some morphemes”.

Pike (1948:5) draws a distinction between register tone languages and contour tone languages. In a pure register tone language, tone contrasts consist of different levels of steady pitch heights in which the tones neither rise nor fall in their production. A pure contour tone language consists of some tones which are not level in their production but rather rise, fall or rise and fall in pitch (Hyman,

1975:214). xlv

Atsam language attests only register tone consisting of High tone represented as [/] ), mid tone (unmarked) and low tone (represented as [ \ ]). The distribution of these tones are given below:

High tone

[ járd ] ‘beard’

[ tám ] ‘chin’

[ wũ ] ‘nose

[ tõ ]

‘ear’

[ rík ] ‘rope’

Mid tone

[ paak ] ‘knife’

[ rias ] ‘man’

[ ʃuɔ ] ‘rat’

[ bĩg ] ‘word’

[ rᴐ ]

‘taste’

Low tone

[ dámi ] ‘hold (in hand)’

[ pì ]

‘belly (external)’

[ ìʤɛ ] ‘penis’

[ tʃì ]

‘fish’

[dárá] ‘guinea corn’ xlvi

2.5 Syllable Inventory of Atsam

The syllable, as a phonological unit, can be considered as the minimal part or component of a word which can be pronounced alone at a single breath.

Hyman (1975:188) claims that the syllable consists of three phonetic parts: (1) the onset, (2) the peak or nucleus, and (3) the coda. Egbokhare (1994) says that the onset of a syllable consists of a consonant occupying the initial position of the syllable; the peak or nucleus consists of a vowel or syllabic consonant occupying the medial part of the syllable; and the coda consists of a consonant occupying the final part of the syllable. The internal structure of the syllable can be formally represented as follows:

Onset

Rhyme

Nucleus Coda

C V C

In human languages, different syllable structures are attested, some of which are: CV, V, N, CCV, VCC, CVC, e.t.c. Among the above, CV structure is the most common. This fact was buttressed succinctly by Malmberg, quoted in

Hyman (1975:188), that, “a syllable consisting of a consonant plus a vowel xlvii

represents the most primitive, and without doubt historically the oldest, of all syllable types, the only one which is general in all languages”.

In addition, a syllable can be open or closed. An open syllable ends in a vowel, while a closed syllable is “checked” or “arrested” by a consonant

(Hyman, 1975:188). In Atsam language, both open and closed syllable types are attested and the predominant syllable structures found in the language are: CVC,

CV, V. Examples of these are provided as follows:

1. CVC

[ t á m ]

‘chin’

CVC

[ j i s ]

‘eye’

C V C

[ l á m] ‘tongue’

C V C

2. CV

[ p ì ]

‘belly (external)’

C V

[ r á ]

‘house’ xlviii

3. V

[ í k a m ì ] ‘know’

V

[ a n a s i ] ‘four’

V

[ a w u r u ] ‘eight’

V

Examples of open syllable structure in Atsam language are:

[ b ὲ r à ]

‘doctor (native)’

[ i bá ] ‘father’

[ gȭzì ]

‘he goat’

[ pɔmù ] ‘hunger’

[ jasi ] ‘fear’

Examples of closed syllable structure in Atsam language are:

[ atʃirim ]‘six’

[ ìjāg ] ‘lick’

[ wãg ] ‘swallow’

[ pɔs ] ‘vomit’

[ fízàk ]

‘spin (thread)’ xlix

2.6 Distinctive features

Oyebade (2008:24), citing Halle and Clements (1983:6), sees distinctive features as a “... set of (articulatory and acoustic) features sufficient to define and distinguish, one from the other, the great majority of the speech sounds used in the languages of the world”. Katamba (1989) claims that the theory of distinctive feature assumes that there is a universal inventory of phonological elements from which different languages draw in building up their phonological systems.

Therefore, we can regard distinctive features as the smallest constituents of phonological structure that are used to describe the phonetic properties inherent in the sound inventory of a language. According to Guessenhoven and Jacobs

(1988:59), the three requirements we must impose in a distinctive feature system are:

(1) They should be capable of characterizing natural segment classes.

(2) They should be capable of describing all segmental contrasts in the world’s languages.

(3) They should be definable in phonetic terms.

In addition, in designating the sound inventory of any language with distinctive or phonological features, there is the use of concept ‘binary’. By definition, a binary feature either has the value ‘+’ or the value ‘-’ which indicates the presence or absence respectively of a feature in a segment. In other words, the feature is present, while the feature value ‘-’ shows the absence of a feature. The features matrix of Atsam consonant sounds are provided below: l

p B t d k g k p g b k w g w f v s z

∫ h t s t

∫ d

З m n ŋ l r j w

Cons + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + +

Syll - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Son - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - + + + + + + + +

Cor - - + + - - - - - - - - + + + + + + + - + + - + + + -

Ant + + + + - - - - - - + + + + - - + - - + + - - + + - -

Lab + + - - - - + + + + + + - - - - - - - - + - - - - - +

Cout - - - - - - - - - - + + + + + + + - - - - - - - - -

Nas - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - + + + + - - - -

Strid - - - - - - - - - - - + + + - - + + + - - - - - - - -

Voic ed

- + - + - + - + - + - + - + - - - - + + + + + + + + +

Lat - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - + - - - delre l

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - + - - - - - - - - - - li

2.6.1 Justification of the Features Used

The distinctive features used above in designating all the consonants of

Atsam are described as follows:

1. [+ cons]: consonantal sounds are produced with a sustained vocal tract constriction at least equal to that required in the production of fricatives.

2. [+ syll]: syllabic sounds are those that constitute syllable peaks, nonsyllabic sounds are those that do not

3. [+ son]: sonorant sounds are produced with a vocal tract configuration sufficiently open that the air pressure inside and outside the mouth is approximately equal

4. [+ cor]: coronal sounds are produced by raising the tongue blade towards the teeth or the hard palate.

5. [+ ant]: Anterior sounds are produced with a primary constriction at or in front of the alveolar ridge.

6. [+ lab]: labial sounds are formed with a constriction at the lips.

7. [+ cont]: continuants are formed with a vocal tract configuration allowing the air stream to flow through the midsaggital region of the oral tract.

8. [+ nas]: In the production of a nasal sound, the velum is lowered to allow air to escape through the nasal cavity.

9. [+ strid]: strident sounds are produced with a complex constriction forcing the airstream to strike two surfaces, producing high intensity fricative noise. lii

10. [+ voiced]: voiced sounds are produced with a laryngeal configuration permitting periodic vibration of the vocal cords.

11. [+ lat]: lateral sounds are produced with the tongue placed in such a way as to prevent the air stream from flowing outward through the centre of the mouth, while allowing it to pass over one or both sides of the tongue

12. [+ Delrel]: This feature is only applicable to sounds produced in the mouth cavity and distinguishes stops from affricates. In stop, the closure is released abruptly while in affricates it is released gradually.

The distinctive feature matrix of Atsan vowels are provided below:

I e ɛ a a: o ɔ

U

Syll + + + + + + + +

High +

Low -

Back -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

+

+

-

+

+

-

-

+

-

-

+

+

-

+

Round -

ATR +

-

+

-

-

-

-

-

-

+

+

+

-

2.6.2 Justification of the Features Used

The features used for designating vowels of Atsam are described below:

+

+

1. [+ syll]: syllabic sounds are sounds which function as syllabic nuclei

2. [+ high]: High sounds are made with the tongue raised from neutal position. liii

3. [+ low]: low sounds are produced with the tongue depressed and lying at a level below that which it occupies when at rest in neutral position.

4. [+ back]: sounds produced with the body of the tongue retracted from neutral position are back.

5. [+ round]: Rounded sounds are produced with a pursing or narrowing of lip orifice.

6. [+ ATR]: sounds with [+ATR] involves drawing the root of the tongue forward, enlarging the pharyngeal cavity and often raising the body of the tongue as well. liv

CHAPTER THREE

PHONOLOGICAL PROCESSES IN ATSAM

3.1 Introduction

Having examined in chapter two, the sounds of atsam language, we discuss , in this section i.e chapter three the phonological processes attested in

Atsam language, Among theses are: assimilatory processes such as nasalization, labialization and palatalization; insertion and deletion.

3.2 Phonological processes defined

When morphemes are combined to form words, the segments of neighbouring morphemes become juxtaposed and sometimes undergo changes.

Changes also occur in environments other than those in which two morphemes come together – for example, word initial and word final positions, or the relation of a segment vis-à-vis a stressed vowel. All such changes will be called phonological processes (Schane, 1973:49). From another perspective, Oyebade

(2008:61) maintains that phonological processes are sound modifications motivated by the need to maintain euphony in a language or to rectify violations of well-formedness constraints in the production of an utterance. He observes further that phonological processes come about so as to maintain the musical quality of the utterance or to make its production smooth and easy to release the articulatory contact in the production of one sound and to initiate a different articulatory contact for a contiguous sound.

In essence, phonological processes are the processes that characterize the changes which occur in the sound system of a language most especially when lv

morphemes are combined to form words as Schane (1973) has rightly observed.

Additionally, it is worthy of mention that the phonological processes of a language are explicitly characterized by the phonological rules converting underlying representations to derived ones (Schane, 1973). He clearly opines that, “if we can state the exact conditions under which a phonological process takes place, we have in effect given a rule”. Summarily, it is the phonological rules that explain and formalize the processes (changes) occurring in a given language.

3.2.1 Assimilation/assimilatory processes

Oyebade (2008:62) observes that, when two contiguous sounds which have different modes of production become identical in some or all of the features of their production, assimilation has taken place. Likewise, Schane

(1973:49) claims that, in assimilatory processes, a segment takes on features from a neighbouring segment. This he means by saying that a consonant may pick up features from a vowel, a vowel may take on features of a consonant, one consonant may influence another, or one vowel may have an effect on another. In his own opinion, Katamba (1989) considers assimilation as the modification of a sound to become more like the sound in its neighbourhood.

Again, Oyebade (2008:62-63) states that the assimilation may be total, converting the changing segment to become identical to the other segment or it may be partial such that only some feature of the changing consonant (or vowel) becomes identical with that of the initiating segment. lvi

Furthermore, the direction of assimilation occurring in a given language may be progressive, regressive or bi-directional. An assimilation is progressive when the first segment changes to become like the second one; it is regressive when the second segment changes to become like the first segment; it is bidirectional when the first and second segments influence each other simultaneously or reciprocally.

Finally, it should be noted that assimilation can occur both within and across morpheme(s). If the assimilation takes place within a morpheme, it is said to be intra-morphemic while it is inter-phonemic if it occurs between two morphemes i.e. when two morphemes are combined.

3.2.1.1 Nasalization

Nasalization is a consonant feature that is assimilated by a vowel whereby an oral vowel becomes phonetically nasalized when adjacent to a nasal consonant (Schane, 1973:50). Examples of this assimilatory process in Atsam language are provided below: rũn [ r ũ ]

‘knee’ ruwunt [ r ù w ũ t ] ‘dry season’ yonk [ j ɔ k ]

‘horn’ yunk [ j ũ k ] ĩnká [ ĩ k á ]

‘mosquito’

‘mother’ lvii

ĩnbá [ ĩ b á] tʃãn [ t ʃ ã ] anãn [ a n ã ]

‘father’

‘child’

‘children’ atunwon [ a t u n w ɔ ]‘five’ sũnzí [ s ũ z í ] ‘sew’

From the above given data,it is observed that vowels [ u, i , a, ɔ] become phonetically nasalized as a result of their occurrence in the environment of a nasal consonant. On this premise two phonological rules can be proposed to account for the above phonological phenomenon: lviii

Rule 1: A vowel is nasalized if it occurs before an alveolar nasal consonant.

+ syll

- cons

+ nas

+ cons

+ cor

+ ant

+ nas

Rule 2: A word final alveolar nasal consonant becomes deleted after a nasal vowel.

+ cons + syll

+ cor - cons

+ ant + nas

+ nas

3.2.1.2 Labialization

Following the positions of Oyebade (2008) and Schane (1973), labialization is a feature of vowels that is superimposed on adjacent consonants.

Oyebade (2008) considers labialization as the superimposition of lip rounding on a consonant. In labialization, the lip position of a rounded vowel induces a secondary articulation onto the consonant (Schane, 1973:50). In their account of labialization, Gussenhoven and Jacobs (1998:9) observe that, during the articulation of the consonant, the lips are rounded. This assimilatory process is lix

demonstrated by some Atsam consonants when they occur before contiguous rounded vowels. Examples of this phonological process are given below:

[ gʷùmù ] ‘short (of stick)’

[ g w orò ] ‘kolanut’

[ k w úù ] ‘okra’

[ z

[ k w w om]

úp ]

[ ʃ w uɔ]

[ s w ɔk]

‘body’

‘bone’

‘rat’

‘bee’

[ s w ús w ɔ] ‘female’

[ d w òd w ó ] ‘fetish (juju)’

[ wɔg w ùr ] ‘left’

In the above data, it can be observed that consonants [ g, k, z, s, ʃ, d] are superimposed with the labiality feature by their adjacent vowels. A phonological rule accounting for this is postulated thus: A consonant becomes labialized before a rounded vowel.

+cons +syll

- syll

+ round -cons

+round lx

3.2.1.3 Palatalization

This assimilatory process is also a vowel feature that is assimilated by consonant. In palatalization, the tongue position of a front vowel is superimposed on an adjacent consonant (Schane, 1973:50). Gussenhoven and Jacobs (1998:9) describe palatalization as the raising of the front of the tongue as for [i] or [j], during the pronunciation of a consonant. Similarly, Oyebade (2008:65) observes that, a consonant manifests a secondary articulation of palatality if the segment following it is a front vowel. Examples of this phenomenon in Atsam language are cited as follows:

[g j ìjá ] ‘arrive’

[ jìg j ítòr] ‘defecate’

[ k j ì ]

[ k j ìtsì]

‘grass’

‘cover (in hand)’

[ ʃùsɔg j íra ] ‘dwell’

[ tárk

[ pérk j j

í]

í]

‘tear (tree)’

‘hot (as fire)’

[ sùrùk j í ] ‘in law’

[ námg j ítʃe ] ‘animal’

[ nág j ítʃe ] ‘buffalo (bush cow)’

The above cited examples from Atsam illustrate that the velar consonants

[k and g] are secondarily modified with the palatality feature of the high front vowel [i] such that they become palatalized. This makes these consonants to be partly made at the palatal region since the high front vowel is contiguous to lxi

them. A rule accounting for the above therefore says that: A velar consonant becomes palatalized before an adjacent high front vowel.

+ cons +syll

- cor

- ant

+ high - cons

- back

+ high

3.2.2 Deletion

According to Oyebade (2008:69), deletion “involves the loss of a segment under some language – specifically imposed conditions”. He submits further that deletion could involve vowels or consonants. In Atsam language, vowel deletion is more prominent than consonant deletion based on the present research. Therefore, instances where vowel is deleted in Atsam are considered below:

/ kúrú +

ábáá / → [ kúrabáá

] ‘twenty’

ten two

/ kúrú +

átáák / → [ kúratáák

] ‘thirty’

ten three

/ kúrú + anasi

/ → [ kúranasi

] ‘forty’

ten four lxii

/ kúrú + atuwon

/→ [ kúratuwɔn

] ‘fifty’

ten five

/ kúrú + atʃirim

/ → [ kúratʃirim

]

‘sixty’

ten six

In the above numeral formation in Atsam, it can be discovered that the final vowel of the first word disappears when it is joined to another word beginning with a vowel. On this premise, a phonological rule which will account for this is postulated as follows:

+ syll + syll

+ back + back

+ high + low

3.2.3 Insertion

Following Oyebade (2008:74), “insertion is a phonological process whereby an extraneous element not present originally is introduced into the utterance usually to break up unwanted sequences”. In Atsam language, it is discovered that in some numeral formation, when two morphemes are combined to form words such that the last vowel of the first word is deleted before the second word beginning with a vowel as shown in deletion process above, there will then be an insertion of a consonant after the deletion process. This lxiii

observation can be buttressed empirically using the following data as a medium of exemplification.

/kúrú + ábáa / →[kúrnábáá] ‘twelve’

ten two

/kúrú +

átáak / → [kúrnátáak] ‘thirteen’

ten three

/kúrú +

ánásí / → [kúrnánásí] ‘fourteen’

ten four

/kúrú +

átúwón /→ [kúrnátúwón]‘fifteen’

ten five

/kúrú + atʃirim /→ [kúrnatʃirim]‘sixteen’

ten six

/kúrú + áta:ríbá /→ [kúrnáta:ríbá]‘seventeen’

ten seven

/kúrú +

áwúrú /→ [kúrnáwúrú]‘eighteen’

ten eight

From the ample data given above, it can be observed that there is an insertion of an extraneous consonant after the deletion process in the final derivation of the numerals. Therefore, we can postulate a phonological rule which will account for such phonological process in the following way: Insert an alveolar nasal consonant before a low back unrounded vowel at morpheme boundary. lxiv

+ cons

+ cor

+ ant

+ nas

+ syll

+ back

+ low

- round lxv

CHAPTER FOUR

ATSAM TONOLOGICAL AND SYLLABLE PROCESSES

4.1 Introduction

In this chapter, we discussed the processes involved in the tone configuration and syllable pattern in Atsam language. It focused on how tones co-occur in the language, including their function as well as the various syllable structures in the language.

4.2

Defining a tone language

Pike (1948:3) defines a tone language as a language “having significant, contrastive, but relative pitch on each syllable”. Welmers (1959:2) proposes that

“a tone language is a language in which both pitch phonemes and segmental phonemes enter into the composition of at least some morphemes”. A tone language is qualified as one if it makes use of at least two level tones.

In human languages, two distinctions of tones are often made. For instance, Pike (1948:5) draws a distinction between register tone languages and contour tone languages. According to him, “in a pure register tone language, tone contrasts consist of different levels of steady pitch heights, that is, perceptually, such tones neither rise nor fall in their production”. Pike claims that, “a pure contour tone language consists of some tones which are not level in their production but rather rise, fall, or rise and fall in pitch”. In general, African tone languages are of the first type while oriental languages are of the second

(Hyman, 1975:214). lxvi

In tone languages, the tone bearing units are usually the vowels and syllabic consonants. Almost all African languages are tone languages except few, and Atsam language is not an exception.

4.2.1 Atsam tone typology

Atsam language makes use of register tones. Register tones are level tones which maintain a steady pitch. Also, there is regularity of the state of pitch, unlike in contour tones. The three commonly cited examples of level or register tones are:

(i) High tone: Which is marked with an acute sign [ / ].

(ii) Mid tone: Which is marked by a macron [−] or sometimes unmarked orthographically in certain languages.

(iii) Low tone: Which is marked by a grave sign [ \ ].

In Atsam language, all the above three level tones are attested, only that the mid tone is not marked by any sign in the orthographic system of the language. Thus, any toneless syllable in the language has an underlying mid tone configuration.

4.2.2 Co-occurrence of tones in Atsam

By this, we mean the phonological distribution of different level tones in a single word. What this implies is that certain level tones select one another and lxvii

co-occur without any restriction or constraint in any phonological word. therefore, in Atsam language, we have the following tone distributions:

High tone co-occurring with high tone

[bétʃí] ‘hair (head)’

[kũtʃú] ‘neck’

[járá]

‘Compound’

[wúríjɔk] ‘Snow’

[góró] ‘Kola nut’

Low tone co-occurring with low tone

[jùàd]

‘Vagina’

[kìtʃì]

[kpèrì]

[vɔrì]

[kpàgì]

‘Close’

‘Open (door)’

‘Plait (hair)’

‘Grind’

High tone and mid tone

[zútʃia] ‘heart’

[kówjε]

[páat]

‘Village’

‘matchet’ lxviii

[jεra]

[kénim]

‘husband’

‘white’

[ʃérì]

[kúù]

[máràk]

[mùari]

[dàmi]

[ìjãg]

High tone and low tone

[wɔkrì]

‘right (side)’

‘Cooking’

‘Okra’

‘extinguish’

‘Kill’

‘hold (in hand)’

‘lick’

Low tone and high tone

[kàrí]

[ìnvã]

‘bite’

‘big’

[tsãmĩ]

[kpàrí]

[ʃìtí]

‘small’

‘fry’

‘cool’

Instances whereby tones are combined in various ways in the language are:

H H H as in [kúráwú]

‘eighty’ lxix

L H H

H L H

L L L

H H L

L M H as in [àtʃítʃí] as in [nízìgĩ] as in [fìtìrì]

‘spit’

‘surpass’

‘turn around’

L H L

H L M as in [jìgítòr] as in [gãzìgã]

‘defecate’

‘split’

L L H H as in [ʃùsɔgírá]

‘dwell’

M M M L as in [rɔmigũkì]

‘carve (wood)’ as in [rívɔrì]

‘rainy season’ as in [kàsuwá]

‘market’

4.2.3 Function of tones in Atsam

In Atsam language, tones perform phonemic or contrastive function whereby they are used to differentiate the meanings of words that have the same orthographic representation.

Examples are given below:

1 (a) [pì]

‘belly (external)’

(b) [pi]

‘stomach (internal)’

2 (a) [kárí] ‘monkey’ lxx

(b) [kàrí] ‘bite’

3 (a) [tʃ i] ‘fish’

(b) [tʃ ì] ‘fat’

4 (a) [zɔm] ‘fat’

(b) [zɔm] ‘body’

From the above given examples, it is observed that even the words are written the same, they have different meaning as a result of the differences in their tonal configuration. On this premise, we say that tones perform phonemic function in

Atsam language.

Also, tones perform grammatical function in human languages but this is not attested in Atsam language with respect to the present research.

4.2.4 Tonological Processes

Tonological processes are the different modifications that tones had undergone before reaching their phonetic manifestation. This underlying process or build-in mechanism responsible in tone languages is referred to as tone processes (Hyman, 1975). In addition, it has to do with the influence of tone on each other or the modification of tone brought about by their interaction and relationship with segments (Schane, 1973). These processes are: lxxi

4.2.4.1 Tonal Spreading

When we have more segments than tone, the tone will then spread to the tone-less segment as it is a must that the segments must bear tone (Hyman,

1975). This does not occur in Atsam language.

4.2.4.2 Tone Stability

Oyebade, citing Goldsmith (1976:30) refers to tone stability as a situation in tone language whereby when a vowel desyllabifies or is deleted by some phonological rule, the tone it was bearing does not disappear, rather, it shifts its location and shows up on some other vowel. With respect to the present research,

Atsam language does not exhibit such stability.

4.2.4.3 Tone Floating

Goldsmith (1976:45) defines a floating tone as “... a segment specified only for tone which, at some points during the derivation, merges with some vowel, thus passing on its tonal specifications to that vowel”. He stresses further that it is a device that has proven useful in working with tone languages but whose theoretical status has always been suspect. For now, this situation is yet to be discovered in Atsam language.

4.3 The Syllable Structure of Atsam

Hyman (1975) observes that a syllable consists of the peak of prominence in a word which is associated with the occurrence of one vowel or a syllabic consonant that represents the most primitive in all languages.

A syllable consists of three phonetic parts namely: lxxii

(i) The Onset

(ii) The Peak or Nucleus

(iii) The Coda

The onset is usually at the beginning of a syllable and always a consonant segment; the peak constitutes the nucleus or the central unit of the syllable and always a vowel or syllabic consonant; while the coda is found at the end of the syllable and always a consonant sound.

In autosegmental phonology of Goldsmith (1976), a syllable is divided into two broad parts:

(i) Onset: Syllable initial segment (consonant)

(ii) Rhyme: Broken down into a compulsory nucleus (vowel or syllabic consonant) and an optional coda (consonant). This can be diagrammatically represented as follows:

Onset

Syllable

Rhyme

C

Peak

V

Coda

C lxxiii

4.3.1 Syllable Typology in Atsam

Studies have shown that in human languages, a syllable can either be open or closed. In his own account of this dichotomy, Hyman (1975: 188) says that, an open syllable ends in a vowel, while a closed syllable is “checked” or “arrested” by a consonant. He remarks further by claiming that, a CV syllable has a core with a zero coda, while a CVC syllable has a core with a V peak and a C coda.

Some languages exhibits only closed syllable type. However, some languages make use of both syllable structures, and this is infact the case with Atsam language. That is Atsam language attests both open and closed syllable types which means that it allows its words to terminate both in a vowel and consonant respectively.

4.3.2 Syllable Structure in Atsam

By this, we mean the rule that states the possible sequence of sounds or segments in a syllable. In Astam language, three major syllable structure are attested they are: CVC, CV, and V.

CVC: This is a sequence of a consonant. Examples are:

[zɔm] ‘body’

[lám] ‘tongue’

[rík] ‘rope’

[wũd] ‘goat’

[vɔb] ‘lie(s)’

CV: This is a sequence of a Consonant and a Vowel. Examples are:

[tʃi]

‘head’

[pì] ‘belly (external)’

[rí] ‘eat’ lxxiv

[ʃú]

‘drink’

[ná] ‘cow’

V: This is a vowel constituting the syllable peak or nucleus. Examples are:

[a bás] ‘urine’

[kúù] ‘okra’

[zεrεε] ‘thread’

[ʤáa] ‘elephant’

[jwáì] ‘snake’

From the evidence given above Atsam exhibits CVC and CV syllable structure, it supports the claim that the language attests both open and closed syllable types. Also, in Atsam language, there are different types of syllable sequence such as monosyllabic words, di-syllabic words, tri-syllabic words e.t.c.

Monosyllabic words

These are words that have a single syllable.

Examples are:

[jis]

‘eye’

[tám] ‘chin’

[ʃú]

‘drink’

[rà] ‘house’

[kì] ‘grass’

[sàk] ‘name’

[sɔk] ‘bee’ lxxv

[ná] ‘cow’

[váp] ‘lizard’

[k w ãk] ‘bat’

Di- syllabic words

These are words that are made up of two syllables. Examples are:

[súsɔ] ‘female’

[jεra] ‘husband’

[káràk] ‘hawk’

[jébéd] ‘toad (frog)’

[kénim] ‘white’

[pérkì] ‘hot (as fire)’

[ʃìtí]

‘cold’

[vòrì] ‘plait (hair)’

[kpàrí] ‘fry’

[ʃámé] ‘buy’

Tri-syllabic words

These are words which have three syllables. Examples are:

[àwúrú] ‘lose (something)’

[nesmígε] ‘look for’

[gùtʃímã] ‘pass (by)’

[fítírí] ‘turn around’ lxxvi

[ìnkára] ‘Here’

[jũgúʃú] ‘Stand (up)’

[atʃirim] ‘six’

[sùrùkí] ‘in-law’

[tsãsusɔ] ‘daughter’

[ĩgùlúk] ‘vulture’ lxxvii

CHAPTER FIVE

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

5.1 Introduction

This chapter presented a brief summary of some of the phonological phenomena raised and discussed in this research work. In addition to some further findings/observations, the chapter concluded the whole work while also suggesting possible recommendations.

5.2 Summary

This long essay has carried out a phonological analysis of Atsam language spoken in Kaduna State, Nigeria.

The first chapter focused on the historical background and the sociocultural profile of the speakers of Atsam language. Likewise, the genetic classification of the language was provided whereby it was established that

Atsam belongs to the platoid group found under the Benue-Congo sub-family of the Niger-Congo phylum. The chosen theoretical framework was also reviewed in the same chapter.

Chapter two addressed certain phonological concepts in Atsam language which included: sound, tonal and syllable inventories as well as the distinctive feature matrix of both the consonants and vowels attested in the language, together with the justification of the features used.

The phonological processes operating on underlying structures to map them into surface structures were examined in the third chapter. These processes were: assimilatory processes such as nasalization; deletion; and insertion.

The fourth chapter discussed the tonal and syllable processes in Atsam language. We established that Atsam operates register tone with three distinct level tones: High, mid and low. Also, it was shown how tones perform phonemic lxxviii

function. In addition to this, the predominant syllable structures in the language were established to be CVC, CV and V.

In chapter five, we gave a brief summary, findings/observations, conclusion and the recommendation suitable for this long essay.

5.3 Findings/Observations

It Atsam language, even though both consonants and vowels are attested, it was observed consonants are more favoured to begin a word in the language than vowels. It was only in few instances vowels begin a word in the language and these vowels are usually [ a ] and [ i ].

Also, it was found out that Atsam words terminate both in vowels and consonants, that is, it makes use of both open and closed syllable typologies.

Another observation in the language was that, even though it allows consonant cluster within a word, it disallows consonant cluster within a syllable.

That is, the two consonants are usually separated such that the consonant on the left becomes the coda of the first syllable while the consonant to the right forms the onset of the second syllable.

Furthermore, it was observed in the language that its vowels can co-occur freely with one another without any co-occurrence restriction or constraint on them. Hence, a strong evidence for the absence of vowel harmony in the language. With respect to tones, we found out that all the three level tones can occur with one another in a single word without any phonological constraint.

Finally, it was observed that it is very rare for a word to begin with a mid tone in Atsam language. Most words begin with either high or low tone, only in few exceptions can words start with a mid tone in the language.

5.4 Recommendation

Owing to the fact that this long essay has only investigated aspects of the phonology of Atsam, it suffices to recommend that further researches into other lxxix

aspects of the language, namely: morphology and syntax should also be encouraged. In addition to this, since this research work qualifies as a reliable reference source, it is pertinent for other linguists and teachers alike to probe more into the phonology of Atsam language most especially the suprasegmental aspect with respect to tonal processes.

5.5 Conclusion

Within the framework of generative phonology, this long essay has addressed some issues relating to the phonology of Atsam language. The essence of this lies in the attempt to develop the language like other Nigerian languages.

Therefore, we can conclude by saying that the findings in this research would serve as reliable point of reference for further linguistic researches into the language as a means of linguistic development of the language. lxxx

References

Aronoff, M and J Rees-Miller (editors). 2001. The handbook of linguistics.

Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics.oxford: Blackwell. Xvi-823

Beegeale O.(2010). Paradigm Shift in the Politics of Kaduna State.

Blench R.M. (1987). A revision of the Index of Nigerian Languages. The

Nigerian Field, 52:77-84