Unit - Achievement First

Unit 3 – Features of Nonfiction Text

Subject: Reading

Duration: 6-8 days

Grades: 7 th and 8 th

Connection to Past Learning and Unit Overview

In Unit 3 – Features of Nonfiction Text, scholars will shift gears from a predominate focus on fiction texts to nonfiction texts. Scholars need the necessary skills and the opportunities to access and critically analyze nonfiction texts. Whether reading instructional manuals, informational brochures, the newspaper, a personal essay in a magazine or an advertisement, scholars must know how to determine the big ideas inherent in the features and content of the text, as well as how to evaluate the author’s purpose and their own relationship to that purpose.

Many of the nonfiction materials our scholars confront (which is also the majority of the text they encounter outside of school) is presented as fact or truth. Scholars must be given the opportunity to engage in texts that present both a measured view and an opinionated view of a topic, so they can weigh these varied “truths.” Ultimately, scholars should develop the skills to become critical of everything they read, particularly when confronting nonfiction texts that present opinions as truth.

This short, six to eight day unit builds on nonfiction units taught in earlier grades. It focuses on how to access nonfiction through the THIEVES strategy, how to use the structure and organization of text to derive meaning, and how to evaluate the messages therein. If your scholars are working regularly with nonfiction in their Textual

Analysis class, you may want to skip this unit, while ensuring that you incorporate nonfiction texts into your other units. If you do not teach this unit, you should review the

AIMS to be sure to spiral the skills and strategies from this unit into the other work you do with your scholars. Although scholars will have worked toward these AIMS last year, you should up the rigor by pairing them with higher-level or more nuanced texts.

You can also increase the rigor by conducting a comparative analysis of texts around a central theme and continuing to employ the critical lens that scholars used in the previous two units: Reading is a Conversation Between Reader, Author and Text.

Perhaps even more than in the first two units, Unit 3 offers scholars an opportunity to weigh the relationships between author and text and text and reader. Non-fiction texts require astute awareness of bias on the part of the author and reader, understanding of purpose for the writing, and the ability to assess a text against one’s own thinking and beliefs. As you move forward through this short unit, consider choosing a thematic

2

focus that will incite strong and varied opinions amongst your scholars. Allow them access to multiple texts that take vastly different stances or approaches to the same big idea. Give scholars opportunities to talk to one another, defend their ideas and write about their thinking to become a reciprocal part of the “conversation.” In this way, the work your scholars do will be rich. Because of its length, this unit will be foundational to future units in non-fiction and multi-genre analysis, but its delivery need not be rote.

Of course, it is imperative that your scholars independently read nonfiction texts during this unit, as well as engage with them during your mini-lessons. If selecting a single, whole class text for independent reading, make certain to choose one that embodies the varied text features presented in this unit. Additionally, you will want to vary the non-fiction genres of text you select for your mini-lessons, so that scholars are exposed to a wide variety of non-fiction texts. Alternately, you may choose to bundle various texts (informational articles, persuasive essays, editorials or speeches, advertisements, task or “how-to” articles and excerpts from biographies, memoirs and autobiographies) around a topic or theme of interest for scholars to read independently. In that way, you may more easily match your modeled instruction to independent text selection. This would also be an excellent opportunity to differentiate to your scholars’ independent levels and/or interests.

This unit includes a diagnostic assessment that will help you to tailor your AIMS sequence for the specific needs of your class. You may need to slow down or speed up instruction of the AIMS to meet your scholars’ varied needs. We recommend giving the diagnostic assessment on a Friday or during the previous unit so that you give yourself some time to adjust your AIMS based on the analysis of your class results.

As with prior units, we have indicated Bottom-Line AIMS. While all of the AIMS in this unit are important, the Bottom-Line AIMS should be taught to mastery during this unit. The

Additional AIMS can be introduced during this unit, but scholars will not necessarily need to demonstrate mastery until a later unit. Extension AIMS have also been included for those scholars (or whole classes) who master the Bottom-Line AIMS quickly and need an added challenge.

Essential and Guiding Questions

These essential questions will continue to act as an umbrella over our scholars’ thinking about text throughout the 2010-2011 year and will be returned to in future units:

1.

How do our identities as readers impact the way we read?

3

2.

What aspects of ourselves (culture, family, past, race, class, gender, age, ethnicity, language, etc.) do we bring into the conversations we have with others about text?

3.

How do multiple perspectives (author, narrator, intended audience) impact our interactions with a text?

4.

Given that everyone has unique interactions with texts, how can we best support ourselves in our analysis so that our perspectives are clear?

Although the essential questions are broad, the guiding questions, included below, should help you to narrow your scope for the first unit:

Essential Questions

1.

How do our identities as readers impact the way we read?

2.

What aspects of our identities (culture, family, past, race, class, gender, age, ethnicity, language, etc.) do we bring into the conversations we have with others about text?

Guiding Questions

What do I already expect to encounter in a nonfiction text?

What assumptions do I make based on headlines and/or images?

What key ideas can everyone take away from a text, regardless of personal identity?

What conclusions does the author urge me to draw, and how are these similar or different to ideas I already have?

3.

How do multiple perspectives (author, narrator, intended audience) impact our interactions with a text?

4.

Given that everyone has unique interactions with texts, how can we best support our analysis?

Who is “speaking” in a text and to what audience is the author “speaking?”

What details add up to the main idea?

Enduring Understandings and Learning Outcomes

By the end of this unit, scholars will be able:

To deconstruct the features of a nonfiction passage through use of the

THIEVES strategy within independent nonfiction texts;

To conclude the main idea of a nonfiction text by paraphrasing and “adding up” its topic sentences within independent nonfiction texts;

To defend their evaluation of a nonfiction text through citation of textual evidence that most strongly supports their conclusions within independent nonfiction texts.

4

Notes on UNIT Vocabulary

Instructional Implications

While vocabulary has not been explicitly included in the AIMS or sample lessons, it may be necessary to teach and/or review key academic language that you will use in your instruction of this unit.

Brief opportunities may be built in during the Do Now, the mini-lesson or in homework to teach and/or review these words. However, these opportunities should not become whole vocabulary lessons and should not take the place of your regular vocabulary program.

In addition to the unit-specific academic vocabulary list, the words from the 7 th and

8 th grade vocabulary units are listed on the right. Because the Literature units and vocabulary units are not aligned, you will need to confer with the vocabulary teacher to make sure these word lists match the instruction your scholars are receiving. However, each word list within a unit should take between two to three weeks to teach, so these words will likely be taught in concurrence with this

Literature unit. (Find the vocabulary units here on the shared server:

C u r r i c u l u m >

S h a r e d D o c u m e n t s > M i d d l e S c h o o l >

V o c a b u l a r y > U n i t M a t e r i a l s > S c h e d u l e a n d L i s t

( W o r d o f t h e D a y , M o r p h o l o g y )

Continue to be thoughtful about how you might encourage scholars to use the words from the vocabulary unit within your class. The words that may best integrate into the unit are bolded. However, scholars will be steadily exposed to all of these words through their vocabulary program and any of them might surface within their reading.

For a great article on embedding academic language into your instruction, read this article by Himmele and Himmele.

Vocabulary

Academic

Evaluate

Text Features

Bias

Persuasive

Informational

Objective/Subjective

Analysis

7 th Grade

Retract

Considerable

Variable

Permeate

Seldom

Reciprocate

Continual

Criticism

8 th Grade

Allegory

Analogy

Thesis

Norm

Devoid

Deconstruct

Inundate

Imperceptible

5

Assessments

Below are descriptions and links to the diagnostic, formative and summative assessments for Unit 3. The formative assessments are suggestions that may be used daily, weekly, and in combination to measure scholars’ progress toward unit goals. The diagnostic exam is directly aligned to the summative assessment, which should be delivered uniformly across the grade in order to accurately measure scholars’ achievement.

F&P scores

Unit 3 Diagnostic

Assessment

Do Nows

Class work artifacts from reading notebooks, graphic organizers, class or small-group discussions, etc.

Scholar-teacher conferences and guided reading groups

Exit tickets

Unit 3 Summative

Assessment

6

Bottom-Line and Additional AIMS + Suggested Sequencing

There are three Bottom-Line AIMS that must be explicitly taught to mastery for all scholars by the end of Unit 3, for which you have a six to eight day window. The

Bottom-Line AIMS are bolded and highlighted, below. Ultimately, every scholar, regardless of his or her starting point, will be held accountable to the same summative assessment, which is designed to test your scholars for mastery of the Bottom-Line AIMS.

Each Bottom-Line AIM should be considered a benchmark along the road of your instruction for this unit. While each of the Bottom-Line AIMS must be reached, the order of your arrival or the length of time you spend devoted to reaching each benchmark may not be the same for each of your classes. Therefore, the AIMS need not be taught in the order in which they’re listed.

The Additional AIMS, bulleted underneath each of the Bottom-Line AIMS, include spiraled review AIMS from last year and the previous unit. You will use your professional judgment to determine which of the Additional AIMS need extra attention, integrating into other lessons, or cutting out in order to lead your scholars to their goals for the unit.

The instructional path you take through the Additional AIMS to reach the Bottom-Line

AIMS may vary widely depending on the diagnostic data you gather from the assessment. In this way, you can tailor your instruction to the differentiated needs of your scholars.

Finally, there several Extension AIMS listed below for a class (or small group of scholars) that quickly masters the Bottom-Line AIMS and needs more rigorous challenges within the unit.

In order to help you tailor your AIMS sequence to the needs of your scholars, this section also includes three Sample AIMS Sequence Calendars. The first two sequence calendars have been filled in to demonstrate how you might plot your AIMS for classes at very different levels. The third calendar is blank. Use it to fill in the AIMS sequence that will work best for your scholars.

7

Bottom-Line and Additional AIMS

Bottom-Line AIM #1.1: SWBAT deconstruct the features of a nonfiction passage through use

of the THIEVES strategy.

1.2) SWBAT critique the structure an author uses to organize a text, including how the major sections contribute to the whole and to the development of the ideas.

Bottom-Line AIM #2.1: SWBAT conclude the main idea of a nonfiction text by “adding up”

its topic sentences into a summary.

2.2) SWBAT retell the key ideas of a nonfiction text by determining the main idea of several paragraphs.

2.3) SWBAT analyze the development of a central idea of a nonfiction text over the course of the text, including its relationship to supporting ideas.

Bottom-Line AIM #3.1: SWBAT assess an author’s conclusions in a nonfiction text through evaluation of text evidence.

3.2) SWBAT produce a response to the author’s point of view or purpose in a text through written reaction to nonfiction text.

Extension AIMS

1.

SWBAT analyze how two or more authors writing about the same topic shape their presentations of key information by emphasizing different evidence or advancing interpretations of facts.

2.

SWBAT evaluate the structure of a specific paragraph in a text, including the role of particular sentences in developing and refining a key concept.

3.

SWBAT compare and contrast two or more texts provide conflicting information on the same topic and identify where the texts disagree on matters of fact or interpretation.

Notes on Behavioral and Procedural AIMS

This unit does not include specific behavioral or procedural AIMS. As you tailor your lessons, continue to keep in mind the ways in which you might incorporate behavioral and procedural expectations into your instruction.

8

Sample AIMS Sequence Calendar #1

This sample AIMS sequence calendar is designed for a class that may have mastered some or several of the AIMS on the diagnostic assessment and may need to spend less time on the Additional AIMS and Bottom-Line AIMS. This sample sequence has been adjusted to include extension AIMS that would extend the learning and increase the rigor of the unit.

Day 1

1.1) SWBAT deconstruct the features of a nonfiction passage through use of the THIEVES strategy.

Day 6

3.1) SWBAT assess an author’s conclusions in a nonfiction text through evaluation of text evidence.

Day 2

EA 1) SWBAT analyze how two or more authors writing about the same topic shape their presentations of key information by emphasizing different evidence or advancing interpretations of facts.

Day 7

3.2) SWBAT produce a response to the author’s point of view or purpose in a text through written reaction to nonfiction text.

2.1) SWBAT summary.

Day 3 conclude the main idea of a nonfiction text by adding up its topic sentences into a

Day 8

EA 3) SWBAT compare and contrast two or more texts that provide conflicting information on the same topic and identify where the texts disagree on matters of fact or interpretation.

Day 4

3.1) SWBAT assess an author’s conclusions in a nonfiction text through evaluation of text evidence.

INTRODUCE NEW

UNIT

EA 2) SWBAT evaluate the

Day 5 structure of a specific paragraph in a text, including the role of particular sentences in developing and refining a key concept.

INTRODUCE NEW

UNIT

9

Sample AIMS Sequence Calendar #2

A class that scored lower, overall, on the diagnostic may need more scaffolding and practice toward mastery of the Bottom-Line AIMS. You may also use lower-level texts within the mini-lessons. If your readers are not yet strategic, you may need to integrate a few lessons from the 5 th grade “Fix-It” unit (see the resources section) to reconfigure your AIMS sequence.

Day 1

1.1) SWBAT deconstruct the features of a nonfiction passage through use of the THIEVES strategy.

Day 6

3.1) SWBAT assess an author’s conclusions in a nonfiction text through evaluation of text evidence.

Day 2

1.1) SWBAT deconstruct the features of a nonfiction passage through use of the THIEVES strategy.

Day 7

3.1) SWBAT assess an author’s conclusions in a nonfiction text through evaluation of text evidence.

Day 3

2.2) SWBAT retell the key ideas of a nonfiction text by determining the main idea of several paragraphs.

Day 8

3.2) SWBAT produce a response to the author’s point of view or purpose in a text through written reaction to nonfiction text.

2.1) SWBAT conclude the

Day 4 main idea of a nonfiction text by adding up its topic sentences into a summary.

Day 9

INTRODUCE NEW

UNIT

Day 5

2.1) SWBAT conclude the main idea of a nonfiction text by adding up its topic sentences into a summary.

Day 10

INTRODUCE NEW

UNIT

10

6

1

Sample AIMS Sequence Calendar #3

Use this blank calendar to plot the AIMS sequence and stamina increments that are most appropriate to your class, based on your diagnostic results. You should also plot behavioral and procedural AIMS that you wish to integrate into your instruction. Each space may also be used to list the scholars who, based on their diagnostic data, may need added attention during small group instruction or

2 conferencing for each of the AIMS.

3 4 5

7 8 9 10

11

Resources

Click here for more ideas on teaching the THIEVES strategy.

Read Chapter 7, “Reading Nonfiction: Learning and Understanding” from Stephanie

Harvey’s book, Nonfiction Matters: Reading, Writing, and Research in Grades 3-8

(Stenhouse Publishers, 1998) for more great insights on the rationale and best methods for teaching nonfiction texts. (Included as a separate document on

Shared Server.)

Read Chapter 2, “Structures and Strategies That Support the Teaching of Short Texts” from Kimberly Hill Campbell’s book, Less Is More: Teaching Literature with Short Texts

– Grades 6-12 (Stenhouse Publishers, 2007) for ideas about using short texts in your mini-lessons. (Included as a separate document on Shared Server.)

Here are some suggestions for texts and great websites for finding nonfiction material for use in your lessons for Unit 3. Some of these text suggestions may be repeated later in the 2010-2011 scope and sequence, because they work well with multiple units.

Books (and Grade Level Equivalent or

Fountas and Pinnell Level as Available)

Claudette Colvin: Twice toward

Justice by Phillip Hoose (6.8)

Topic: Civil Rights movement; bus boycott

Time For Kids:

Websites www.timeforkids.com

Voices From the Holocaust by Harry

James Cargas

Topic: WWII; Holocaust

Chew On This by Eric Schlosser (8.6)

Topic: The “truth” about fast food

Tolerance.org (Project of the Southern Poverty

Law Center):

www.tolerance.org

PBS for Teachers: http://www.pbs.org/teachers/

New York Times: With Their Eyes: The View From A High

School at Ground Zero edited by

Annie Thomas

Topic: Teens’ reactions to 9/11 www.nytimes.com

CNN www.cnn.com

http://www.cnn.com/studentnews/

The Kid Who Invented the Trampoline and Other Extraordinary Stories about

Inventions by Don L. Wulffson

Topic: Inventions

Los Angeles Times: www.latimes.com

The Freedom Writers Diary with Erin Helpful Kid’s News Site:

12

Gruell (Z)

Topic: Gangs, Education

In These Girls, Hope is a Muscle by

Madeleine Blais (7.5)

Topic: Girls’ sports; Overcoming obstacles

A Night to Remember by Walter Lord

(5.3)

Topic: Titanic

www.kidsnewsroom.org

Sports Illustrated for Kids http://www.sikids.com

National Geographic for Kids: http://kids.nationalgeographic.com/kids

Hole in my Life by Jack Gantos (7.1)

Topic: Drug abuse; Incarceration

Discovery Channel for Kids: http://kids.discovery.com/

Check-out the 7 th and 8 th grade History Scope and Sequence, created by Ali Brown and her fabulous History teachers to create cross-curricular opportunities. In particular, consider each grade’s essential questions for the year, unit specific topics and essential questions for the unit to think about how you can tie them into the reading you do with your scholars

While scholars complete Unit 3 in Literature, 7 th and 8 th graders will complete their first long unit of study in History:

History

Essential

Questions for the

Year

Unit Focus

7 th grade

What does it mean to be

“American?”

What ultimately caused the Civil

War?

New American Colonies and

Native Americans

8 th grade

To what extent is America a land of opportunity?

To what extent have we experienced a rights revolution?

Post-Civil War Legislation and

Reconstruction Efforts

Unit Essential

Questions

How does where you live affect how you live?

Can equality be legislated?

View the full Scope and Sequence here . Use it to help you collaborate with the

History teacher at your school, to make text selections, and to build schema.

For differentiation strategies, check out the tips on the Scholastic website . The article includes a bibliography of books on the subject.

The following chart, shared with us by Maddie Witter and developed by Perkins and

Swarts, helps to think about your scholars’ varied metacognitive abilities as readers.

Use it to adjust your groups of scholars and/or to adjust your mini-lessons. Although ideally all of our 7 th and 8 th grade scholars would be strategic now and working on becoming reflective by the end of the year, some of our scholars are tacit or aware and need differentiated instruction to succeed. In this case, see the 5 th grade Unit 5,

“Fix-It” strategies on the Shared Server for ideas:

C u r r i c u l u m > S h a r e d D o c u m e n t s >

M i d d l e S c h o o l > L i t e r a t u r e > U n i t M a t e r i a l s > 2 0 1 0 - 2 0 1 1 A F G R 0 5 - 0 8 L i t e r a t u r e U n i t s > 5 t h

G r a d e U n i t s > U n i t 5 - - F i x - i t S t r a t e g i e s

13

1.

Tacit

Readers

2.

3.

Aware

Readers

Strategic

Readers

4.

Reflective

Readers

Lack awareness of how they think when they read.

Realize when meaning has broken down or confusion has set in may not have sufficient strategies for fixing the problem.

Use thinking and comprehension strategies to enhance understanding and acquire knowledge. Are able to monitor and repair meaning when it is disrupted.

Are strategic about their thinking and are able to apply strategies flexibly depending on their goals and/or purposes for reading.

Structure of Literature Class

Adapted from Comprehensive Approach to Balanced Literacy 6-9, Section 4, Author

Unknown.

The following chart can be used as a resource to think about how to structure your reading workshop for each of your mini-lessons. The time-frames are conducive to a 45 minute block on the lower end of the time scale and a 60 minute block on the higher end of the time scale.

If your teaching block falls between these two times, and you are unsure how to allocate the extra minutes, it is best to add time to the Independent Practice (“You

Do”) section of the lesson, whenever possible.

In all cases, the mini-lesson should take between five and fifteen minutes, including the time it takes to connect to your lesson from the previous day. The more time you allocate for your scholars to read and engage with their independent texts, the better!

If you frequently find yourself running out of time for a lesson, shorten the DO NOW and share sections of the lesson. You may even shorten the active engagement piece

(“We DO”) and build thoughtful small group or one-on-one conferencing for those scholars who need extra scaffolding and support during independent practice.

The cumulative review section of the lesson includes review of a previous lesson and skills practice.

14

During the connection, teachers tell scholars what they will teach them and how the day’s work will help them to grow as readers. The connection is based on something previously observed or is used to transition to new learning.

What this might sound like:

Yesterday I noticed…

When I was reading your notebooks, I noticed…

During conferences yesterday/this week…

We’ve been working on_____, now it’s time to start working on...

During the teach or mini-lesson component of the lesson, teachers will demonstrate their thinking about a strategy, retell an experience, or model a successful strategy they have observed another reader/writer use.

Think aloud strategies may include: skimming/scanning for main idea and details, using charts, inferential thinking skills, word patterns, locating information, outlining, re-reading, etc.

The mini-lesson may also incorporate word work: vocabulary, comprehension strategies, etc.

What this might sound like:

Today I am going to show you…

Audrey is going to show you…

We have been reading texts by/about _______. Let me show you how I connect (or other strategy) to this text while I read.

During the guided practice, the teacher leads scholars through an opportunity to try what was taught as a whole class. Scholars may work with a partner. This is a “quick try” of what was modeled or during the mini-lesson with declining scaffolding.

What this might sound like:

Look for a place in your story where you can try…

Now it’s your turn, using the paragraph on the overhead (or the handout I distributed), “give-it-a-go…”

Turn to your partner and share…

In the link component of the lesson, scholars are encouraged to transfer the mini-lesson to their independent work for the day.

What this might sound like:

Today when you go off to read, I want you to try and notice…

During your independent reading, I want you to try this strategy…

15

The independent practice and small group work section is an opportunity for scholars to practice the AIM on their own. It is also time for the teacher to meet with small groups of scholars who need scaffolding or extension of instruction and/or conferencing with individual scholars.

What this might sound like:

Chris, can you tell me how your reading practice is going today?

Based on yesterday’s exit ticket, this group is ready for a challenge…

Based on our conferences, I wanted to show all of you another way to tackle…

The share is a follow-up to the mini-lesson. Scholars are gathered (or redirected) to share. The teacher selects scholars to share who have demonstrated a thorough understanding of the AIM. Teachers should administer and collect a quick, formative assessment of class mastery of the lesson’s AIM.

What this might sound like:

Today I noticed that Marissa tried out what I taught today in the mini-lesson. Marissa, can you share how it went?

I conferred with Marcus today, and he tried something that worked for him. Mike will you share with us how you…?

I’d like you to take a moment to complete this exit ticket, so I can see how well each of you has understood today’s AIM…

16

Standards/Performance Indicators Addressed

Common Core State

Standards

7 th grade Reading Standards for

Informational Texts:

Cite several pieces of textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

Analyze the structure an author uses to organize a text, including how the major sections contribute to the whole and to the development of the ideas.

Determine an author’s point of view or purpose in a text and analyze how the author distinguishes his or her position from that of others.

By the end of the year, read and comprehend literary nonfiction in the grades 6-8 text complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.

8 th grade Reading Standards for

Informational Texts:

Cite the textual evidence that most strongly supports an analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the

New York State Standards and

Core Curriculum in ELA

Grade 7

Standard 1: Scholars will read, write, listen and speak for information and understanding.

Interpret data, facts and ideas from informational texts by applying thinking skills, such as define, classify and infer.

Preview informational texts with guidance to assess content and organization and select texts useful for the task.

Distinguish between relevant and irrelevant information

Formulate questions to be answered by reading informational text, with assistance.

Compare and contrast information from a variety of different sources.

Standard 3: Students will read, write, listen and speak for critical analysis and evaluation.

Recognize the effect of one’s own point of view in evaluating ideas, information, opinions and issues.

Standard 4: Students will read, write, listen and speak for social interaction.

Share reading experiences with peers or adults; for example, read together silently or aloud with a partner or in small groups.

Consider the age, gender, social position, and cultural traditions of the writer.

Grade 8

Standard 1: Students will read, write, listen, and speak for information and understanding.

• Apply thinking skills, such as define, classify, and infer, to

Connecticut ELA Curriculum

Standards

Grades 7 & 8

Standard 1: Students comprehend and respond in literal, critical and evaluative ways to various texts that are read, reviewed and heard.

Use appropriate strategies before, during and after reading in order to construct meaning.

Interpret, analyze and evaluate text in order to extend understanding and appreciation.

Determine the main idea of text.

Select and use relevant information from the text in order to summarize events and/or ideas in the text.

Identify or infer the author’s use of structure/ organizational patterns.

Analyze and evaluate the author’s craft including use of literary devices and textual elements

17

text.

Determine a central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text, including its relationship to supporting ideas; provide an objective summary of the text.

Analyze in detail the structure of a specific paragraph in a text, including the role of particular sentences in developing and refining a key concept.

Determine an author’s point of view or purpose in a text and analyze how the author acknowledges and responds to conflicting evidence or viewpoints.

By the end of the year, read and comprehend literary nonfiction at the high end of the grades 6-8 text complexity band independently and proficiently. interpret data, facts, and ideas from informational texts

• Preview informational texts to assess content and organization and select texts useful for the task

• Use knowledge of structure, content, and vocabulary to understand informational text

• Distinguish between relevant and irrelevant information

• Formulate questions to be answered by reading informational text

• Compare and contrast information from a variety of different sources

Standard 4: Students will read, write, listen, and speak for social interaction.

• Share reading experiences with peers or adults; for example, read together silently or aloud with a partner or in small groups

• Consider the age, gender, social position, and traditions of the writer

18

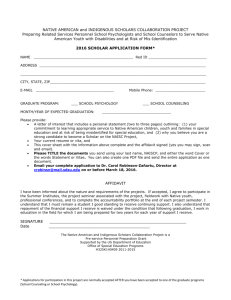

Name:__________________ Class:__________________ Score:_____________

Scale: _______/26

Unit 3 Diagnostic Assessment in Reading

Directions: Read “The Roswell Incident,” by Phillip Brooks. Then, answer all of the questions that follow. Remember, before we start our new unit, this is how you can

Show What You Know so I can teach you better in the days that come! Do your best!

Word Bank: You may need to know the meaning of these words in order to understand the text.

hieroglyphs – picture symbols used for writing

spindly – slender and long

autopsy– the medical examination of a dead body in order to establish the cause and circumstances of death

The Roswell Incident

by Phillip Brooks

Have flying saucers crashed on Earth? Are aliens among us? Strange events that happened in 1947 may make you wonder.

Date: July 3, 1947

Place: Roswell, New Mexico

William “Mac” Brazel rode his horse across the dry desert land of his ranch. He thought about the explosion he had heard last night during a storm. Now he wanted to find out what had caused it.

Something silver glinted in the sunlight, catching Mac’s eye. The ground around him was littered with shiny metal pieces. He stopped to pick one up.

19

The fragment was extremely lightweight but unbendable. And it was covered with

hieroglyphs. Mac felt uneasy. The metal looked like nothing on earth. He telephoned the air force base at nearby Roswell. Staff from the Roswell base arrived at Mac’s ranch. They posted guards around the area where the metal was found.

On July 8, the air force base issued an amazing news statement – they said that the wreckage was from a flying saucer! Later that day, the base released a second statement. It said that the first story was a mistake. The crashed object was in fact a weather balloon. But was it? Were the authorities covering something up?

On the left is the front page of a Roswell newspaper that appeared in 1947. On the right, a member of the Roswell

Army Air Force (RAAF) holds up a piece of the “flying saucer” they later called a “weather balloon.”

Soon there were stories of a second crash site about 100 miles west of Roswell.

An engineer named Grady Barnett said he was working in the desert when he saw a large metal disk on the ground.

Scattered around the crumpled disk were five small, gray bodies. They appeared to be dead. As Grady stood staring, a military vehicle drove up. An officer jumped out. He told Grady to leave at once and, more importantly, never speak about what he had seen. As he was hustled away, Grady glanced over his shoulder. Once of the creatures seemed to open an eye and look back at him.

Grady Barnett said later that the bodies were “like humans, but they were not humans.”

They were small, with spindly arms and legs. Their heads were large, with sunken eyes and no teeth.

20

In the more than fifty years since the actual event, various witnesses have come forward with bizarre stories about the aliens. Some claim the alien bodies were taken to the Roswell Air Force Base.

One story told how doctors at the Roswell Army Hospital had been ordered on duty at short notice. The shocked doctors were told to cut open and examine the bodies of the dead aliens in a procedure called an autopsy. When the bodies were cut open, a terrible smell filled the room. Several doctors became too sick to carry on.

The story took another twist in the 1990s, when a video tape was released. The film was supposed to date from 1947 and show the alien autopsy. But many people believe that the film is a fake and the autopsy never happened.

The Roswell legend has continued to grow. New details have been added, including a rumor that the alien bodies were frozen in ice and kept at a top-secret air force base called Area 51.

It seems certain that something did crash at Roswell in 1947. Does the air force know more than it is telling? Were the stories fake? We may never know.

A photograph of wreckage of the Roswell crash.

21

1.

(1.1) Choose three of the following text features to fill in the blanks, below, and explain how you used each of them to interpret the text as you read: Title, Headings,

Introduction, Each topic sentence, Visuals, or Ending (conclusion).

1.

_________________________________________________

CRITERIA

Scholar can accurately identify and locate the selected text feature.

Scholar understands the purpose of the text feature.

Scholar is able to accurately interpret information from the text feature.

Total:

2.

_________________________________________________

1 POINT EACH

____/3

22

CRITERIA

Scholar can accurately identify and locate the selected text feature.

Scholar understands the purpose of the text feature.

Scholar is able to accurately interpret information from the text feature.

Total:

3.

_______________________________________________

1 POINT EACH

____/3

CRITERIA

Scholar can accurately identify and locate the selected text feature.

Scholar understands the purpose of the text feature.

Scholar is able to accurately interpret information from the text feature.

Total:

1 POINT EACH

____/3

2.

(1.1) What is the difference between the picture of the alien that appears next to the title of the article and the photographs that appear later in the text? Why do you think the author included both in this article?

23

CRITERIA

Scholar can accurately interpret the author’s purpose for including one visual.

Scholar can accurately interpret the author’s purpose for including the other visual.

Scholar is able to derive meaning about the inclusion of both visuals by contrasting the two.

Total:

1 POINT EACH

____/3

3.

(2.1) What is the main idea of this article? Support your answer.

CRITERIA

Scholar identifies main idea of the text.

Scholar summarizes the main idea of the text.

Scholar locates specific, relevant details to support the main idea.

1 POINT EACH

Total: ___/3

4.

(2.1) Which two of the topic sentences in the article best reveal the main idea of the whole article? Explain your choices, below.

24

CRITERIA

Scholar is able to identify one topic sentence that clearly encapsulates the main idea.

Scholar is able to identify two topic sentences that clearly encapsulate the main idea.

Scholar is able to provide clear, logical supporting evidence for choice of topic sentences.

Total:

1 POINT EACH

___/3

5.

(2.3) One important idea in the article, “The Roswell Incident” is that what happened at Roswell continues to be a big mystery. Which additional fact or detail from the article could you add in the space, below, to support this idea?

William “Mac” Brazel discovers unusual metal fragments covered with hieroglyphs on his ranch. The Roswell Air

Force base first calls his discovery a flying saucer, before stating that it was actually a fallen weather balloon.

Many people are curious about the events that happened at Roswell, and rumors about the aliens and

UFOS thought to be discovered there continue to circulate.

CRITERIA

Scholar locates a specific, relevant detail to the important idea expressed in the question.

Total:

1 POINT EACH

___/1

6.

(3.1) Aliens and UFOs are difficult to write about using solid facts. Which are the two strongest facts presented by the author? Explain why they are the strongest.

25

CRITERIA

Scholar selects one strong fact from the text.

Scholar selects another strong fact from the text.

Scholar defends both choices as the strongest facts in the text by making relevant connections to the big ideas of the text.

Total:

1 POINT EACH

___/3

7.

(3.1)Re-read paragraph 4, beginning “On July 8…” Based on the evidence presented in the article, which of the statements issued by the air force base do you think is true? Defend your answer with evidence from the text.

CRITERIA

Scholar gives a clear opinion in response to the question.

Scholar gives multiple (two or more) examples of supporting information from the paragraph to defend his/her opinion.

Total:

1 POINT EACH

___/2

26

8.

(3.2) Imagine that you visited Roswell and saw this in the sky:

Use the photograph and your imagination to write a paragraph that could be included in the article, “The Roswell Incident.” Then, explain why your paragraph belongs in the article.

CRITERIA

Scholar writes a clear, related response to the article.

Scholar clearly and logically connects his/her writing to the article.

Total:

1 POINT EACH

___/2

27

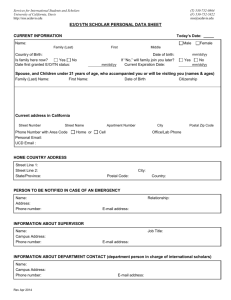

FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT/CONFERENCING SHEET:

Use or modify this conferencing sheet to formatively assess your scholars’ mastery of the unit AIMS. This conference form is meant to be used multiple times over a series of conferences throughout the unit. For instance, assess a scholar’s ability to recall key ideas “Within” the text during one lesson and check “About” the text comprehension during another lesson by asking questions that zone in on author’s craft and text features.

Scholar’s Name:_________________________________________ Unit:_______________________

Text(s):__________________________________________________________________________________

Date Oral Reading Notes (Types of errors, self-corrections, fluency, rate, etc.) : Next Steps:

Comprehension Within the Text (Summary, Recall) :

Questions Asked:

Observations:

Comprehension Beyond the Text (Infer, Connect, Conclude) :

Questions Asked:

Observations:

Comprehension About the Text (Author’s craft/purpose, Text structure) :

Questions Asked:

Observations:

Scholar’s Reading Goal(s):

28

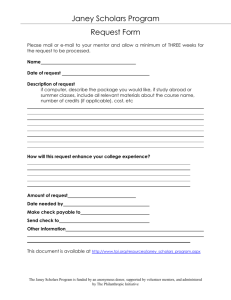

Name:__________________ Class:__________________ Score:_____________

Scale: _______/26

Unit 3 Summative Assessment in Reading

Directions: Read “The School Uniform Question” from Great Essays. As you read, pay careful attention to the features of nonfiction text we’ve learned about in class. Then, answer all of the questions that follow. Be sure to support your answers with text evidence.

Show What You Know!

Word Bank: You may need to know the meaning of these words in order to understand the text.

fundamental – essential; basic

truancy – absence without permission

implementing – putting into effect

flaunt – to show off; to display

The School Uniform Question

from Great Essays

Conformist or responsible? Expressive or distracting?

Individualism is a fundamental value in the United States. All Americans believe in the right to express their own opinion without fear of punishment. This value, however, is coming under fire in an unlikely place – the public school classroom. The issue is school uniforms. Should public school students be allowed to make individual decisions about clothing, or should all students be required to wear a uniform? School uniforms are the better choice for three reasons.

First, wearing school uniforms would help make students’ lives simpler.

They would no longer have to decide what to wear every morning, sometimes trying on outfit after outfit in an effort to choose. Uniforms would not only save time but also would eliminate the stress often associated with this chore.

Second, school uniforms influence students to act responsible in groups and as individuals. Uniforms give students the message that school is a special place

29

for learning. In addition, uniforms create a feeling of unity among students. For example, when students do something as a group, such as attend meetings in the auditorium or eat lunch in the cafeteria, the fact that they all wear the same uniform would create a sense of community. Even more important, statistics show the positive effects that school uniforms have on violence and truancy. According to a recent survey in Hillsborough County, Florida, incidents of school violence dropped by 50 percent, attendance and test scores improved, and student suspensions declined approximately 30 percent after school uniforms were introduced.

Finally, school uniforms would help make all the students feel equal.

People’s standards of living differ greatly, and some people are well-off while others are not. People sometimes forget that school is a place to get an education, not to promote a “fashion show.” Implementing mandatory school uniforms would make all the students look the same regardless of their financial status. School uniforms would promote pride and help to raise the self-esteem of students who cannot afford to wear stylish clothing.

Opponents of mandatory uniforms say that students who wear school uniforms cannot express their individuality. This point has some merit on the surface. However, as previously stated, school is a place to learn, not to flaunt wealth and fashion. Society must decide if individual expression through clothing is more valuable than improved educational performance. It’s important to remember that school uniforms would be worn only during school hours.

Students can express their individuality in the way they dress outside of the classroom.

In conclusion, there are many well-documented benefits to implementing mandatory school uniforms for students. Studies show that students learn better and act more responsibly when they wear uniforms. Public schools should require uniforms in order to benefit both the students and society as a whole.

30

1.

(1.1) Explain how you used the following three text features to interpret the text as you read:

1.

Title

CRITERIA

Scholar can accurately identify and locate the selected text feature.

Scholar understands the purpose of the text feature.

Scholar is able to accurately interpret information from the text feature.

Total:

2.

Visuals

CRITERIA

1 POINT EACH

____/3

1 POINT EACH

31

Scholar can accurately identify and locate the selected text feature.

Scholar understands the purpose of the text feature.

Scholar is able to accurately interpret information from the text feature.

Total:

3.

Introduction

____/3

CRITERIA

Scholar can accurately identify and locate the selected text feature.

Scholar understands the purpose of the text feature.

Scholar is able to accurately interpret information from the text feature.

Total:

2.

1 POINT EACH

____/3

(1.1) What is the difference between the two photographs shown at the beginning of the essay? Why do you think the author included both photographs?

32

CRITERIA

Scholar can accurately interpret the author’s purpose for including one visual.

Scholar can accurately interpret the author’s purpose for including the other visual.

Scholar is able to derive meaning about the inclusion of both visuals by contrasting the two.

Total:

1 POINT EACH

____/3

3.

(2.1) What is the main idea of this essay? Support your answer.

CRITERIA

Scholar identifies main idea of the text.

Scholar summarizes the main idea of the text.

Scholar locates specific, relevant details to support the main idea.

Total:

4.

1 POINT EACH

___/3

(2.1) Which topic sentence in the essay best reveals the main idea of the whole article? Explain your choice.

33

CRITERIA

Scholar is able to identify one topic sentence that clearly encapsulates the main idea.

Scholar is able to provide clear, logical supporting evidence for choice of topic sentence.

Total:

5.

1 POINT EACH

___/2

(2.3) Which additional fact or detail found in the essay could you add in the space, below, to support the argument that school uniforms are the best choice for students?

School uniforms help make students’ lives simpler.

School uniforms influence students to act responsibly.

School uniforms help students feel equal.

CRITERIA

Scholar locates a specific, relevant detail from the text to support the arugument.

Total:

6.

1 POINT EACH

___/1

(3.1) Which are the two strongest arguments made by the author in this essay to support school uniforms in schools. Explain why they are the strongest arguments.

CRITERIA 1 POINT EACH

34

Scholar selects one strong fact from the text.

Scholar selects another strong fact from the text.

Scholar defends both choices as the strongest facts in the text by making relevant connections to the big ideas of the text.

Total:

7.

___/3

(3.1)In paragraph 4, what supporting information does the writer give to show that uniforms make students equal? Is this strong supporting information? Why or why not?

CRITERIA

Scholar gives multiple (two or more) examples of supporting information from the paragraph.

Scholar gives an opinion about the strength of the supporting information and provides a relevant defense of his/her opinon.

Total:

1 POINT EACH

___/2

8.

(3.2) Children are too materialistic these days. They are too interested in wearing

designer clothes and shoes.

What opinion might the author have about this statement? How do you know?

What is your opinion? Support your answer.

35

CRITERIA

Scholar clearly and logically connects the author and essay to the statement.

Scholar expresses an opinion related to the statement and essay.

Scholar clearly and logically supports his/her thinking.

Total:

1 POINT EACH

___/3

36

AIMS Mastery Tracker (Diagnostic to Summative)

Use this spreadsheet to log and track your scholars’ progress from the diagnostic (D) to the summative (S) assessment. The assessments are closely aligned to each other, as well as to the AIMS for the unit. It should give you a clear indication of which

AIMS your scholars have mastered and which need re-teaching or review in subsequent units. Also listed under each AIM are the question numbers on the assessment that correspond to each of the AIMS.

The spreadsheet is formatted as an Excel spreadsheet that you can manipulate directly inside of the document or cut and paste into your Excel program. That way you can tailor it to your needs and have it reflect your scholars’ names and individual scores.

AIM (Bottom-Line

AIMS are shaded.)

Test Type

Scholars

D

1.1

Q: 1,2

S D

2.1

Q: 3,4

S D

2.3

Q: 5

S D

3.1

Q: 6,7

S D

3.2

Q: 8

S

37

Sample Lessons:

A sample lesson has been included for each of the three Bottom-Line AIMS. The lessons draw heavily from ideas and concepts in the book, Nonfiction Reading Power by Adrienne

Gear (Stenhouse Publishers, 2008). These lessons are meant to be used as springboards into your own thinking about lesson planning for this unit and should be used only after they have been tailored to your scholars’ needs. Texts may need to be differentiated for your scholars. Like the content, the process of your lessons will change according to your scholars’ needs and your own preferences. These lessons are not in a fixed order. For extra help organizing the AIMS, see the suggested AIMS sequences on p 8-10.

Note on texts for mini-lessons: These lessons model the way in which you might link short texts around a central idea or topic for your mini-lessons. For these sample lessons, all of the texts center on the topic of food, food production, and health and nutrition. They could be paired the following books (to be read as independent books or in excerpted form): Chew

On This by Eric Schlosser, Fast Food Nation by Eric Schlosser, Peak Performance: Sports

Nutrition by Donna Shrye, Body Fuel: A Guide to Good Nutrition by Donna Shrye, and/or

Weighing In: Nutrition and Weight Management by Lesli J. Favor

There are endless high-interest topics to use to connect your lessons to each other. Obvious considerations are your scholars’ interests, as well as the availability of non-fiction texts and resources at your school. You may also compliment your scholars’ learning in History or

Science by choosing topics related to their current unit of study in one of those classes.

(See the Resources section for links to the History scope and sequence for 7 th and 8 th grade.) Additionally, you may select a whole class non-fiction text that you’re passionate about, then select articles, essays and other nonfiction resources to connect to that text

(i.e. The Freedom Writers by Erin Gruell might pair well with texts on gangs, community, the power of self-expression, and excerpts from Zlata’s Diary by Zlata Filipovic or The Diary of

Anne Frank by Anne Frank).

As always, you should use texts that suit your adaptation of the unit. See additional suggestions in the Resources section, beginning on page 11.

Finally, each of the lessons includes work for scholars in their I-Think Journals. At this point in the year, scholars should be continuously developing an I-Think Journal or other notebook dedicated to their thinking about their reading. Continue to reinforce expectations for use of the I-Think Journal within your lessons.

38

Sample Lesson: Text Features and THIEVES

Teaching Point: Good readers know the common text features of nonfiction texts. They can analyze the features to draw conclusions about the content of the text and the author’s purpose.

AIM: #1.1: SWBAT deconstruct the features of a nonfiction passage through use of the

THIEVES strategy.

Criteria for success (You may choose to explicitly share these during your mini-lesson

OR imply them during your think aloud):

Examine text features: (Title, Headings, Introduction, Every first sentence, Visuals,

Ending, So what?)

Ask: What observations can I make about the text features? What conclusions can I make, based on my observations?

Read the full article to see if my conclusions are correct

So What? Summarize the main idea and my reaction to the article.

Materials:

Visuals and Title from “Too Many Junk Food Ads!” to post or project for

Connection/Hook

Copies and/or means of projecting “Too Many Junk Food Ads!”

Copies of “Warning! Check Your Eggs!” and a means of projecting it for the class.

Visual Anchor: THIEVES

Optional Visual Anchor: Criteria for Success

I-Think Journals

Independent text (or scholars’ independent books)

Homework

Agenda:

1.

Do Now – Parts of the Whole

2.

Mini lesson –THIEVES!

3.

Guided – What can We “Take Away?”

4.

Independent – What can YOU “Take Away?”

5.

Share – Share your Loot!

6.

Homework

Connection/Hook:

Reveal each of the following three nonfiction text features, one at a time.

39

Say: I want you to imagine that each of the following text features I am about to show you is part of the same article. One at a time, you’ll look at the text feature, and write a sentence or short phrase to describe what you think the article is about, based on what you see or read. Your ideas may change or they might stay the same. Write down what comes to mind.

1.

Sample Responses:

This article is probably about

McDonald’s or fast food.

2.

This article might be about how

McDonald’s or other fast food makes people overweight.

3.

Too Many Junk Food Ads!

***

This article might be about how fast food or other junk food companies are contributing to health and weight issues through their advertisements.

Ask: What were your impressions based on the first visual? Why? The second? Third?

How did your conclusions about the topic of the article change as you looked at each of the three text features? (Allow 3-4 scholars to respond. You may want to monitor the room as scholars respond to the prompts to pre-select scholars whose assumptions are correct.)

Say: You’ve drawn some interesting conclusions about this article based on the text features we saw. In a moment, we’ll read the whole article to find out if our conclusions are accurate.

40

Mini Lesson:

Say: When we deconstruct or take apart and examine nonfiction text features, it’s amazing how much information we can gather. Nonfiction texts, whether they’re science textbooks, articles in a magazine, editorials in a newspaper, or advertisements usually include a combination of several text features that give a lot of important information about the main ideas expressed in the text.

Today, we’re going to look a little more closely at the common features of nonfiction texts and practice deconstructing them, or taking them apart, so we can draw accurate conclusions about what the author is trying to tell us. By deconstructing the features, I mean that we’ll look at the information contained in each feature, like we did at the beginning of class, and try to interpret that information. What does each feature reveal about the main idea of the text and the author’s purpose? What conclusions can I make?

First, we have to “take away” information from the text features by identifying and interpreting them. Thieves know where to go in a house, museum or bank to find the

“goods.” We can find the “goods” in a nonfiction text, if we think like “thieves.” To help us, think about the acronym THIEVES (which you might have seen last year). (Reveal visual anchor and ask scholars to take notes.)

T - Title

H - Headings

I – Introduction

(first paragraph)

E – Every first sentence

(of each paragraph)

V – Visuals

(pictures, photos, graphs and captions)

E – Ending

(conclusion/last paragraph)

S – So What?

(summarize your findings from all of the above)

(Talk through each letter of the acronym. Project the article “Too Many Junk Food

Ads!” on the overhead and model labeling each feature. The “So What?” section is a place to summarize the big ideas revealed by the features of the article and include a personal reaction to the text. Scholars will have a chance to practice finding the big idea and interpreting it a lot during this unit. Today, although you’ll determine whether or not your conclusions about the main idea of the article were accurate, you won’t

41

work too long or hard today on perfecting the “So What?” portion of the THIEVES strategy.)

Say: In this article, every one of the text features is included in the article, but it’s important to note that not every text will include every feature.

Say: Now that I’ve found each of the text features, I’ll write down my observations about each one and use my observations to draw conclusions about the main idea.

Say: When I read a nonfiction text, the first features I usually notice are the title, visuals and headings. At the beginning of the lesson, we all did some thinking about what we could “take away” from the visuals and title.

(Model thinking through these two features and jotting down your thinking in a projected I-Think journal. In this case, you may draw on scholars’ observations and conclusions from the beginning of class. You may wish to provide an additional example.

After modeling two to three examples, record a one to two sentence summary in the “So What?” section of THIEVES and a one sentence personal reaction.

You’ll want your scholars to complete the short summary and add their own personal reaction during guided practice.)

T

Feature itle:

Observation

The title “Too Many Junk Food Ads!” already feels like a strong statement against junk food and against advertisements for junk food. I think this, because of the words “too many.”

Usually when someone says there is “too much” of something, it’s because there is an excess of something. In this case, the excess of junk food ads has a negative

Conclusion

Based on the title, I think this article is mostly about how junk food companies and restaurants are negatively impacting people by releasing too many tempting ads. I say junk food companies and fast food restaurants, because those are usually the companies issuing advertisements.

Also, the words “junk food” are used in the

title, but the visuals point to fast food.

H eading(s): impact.

I ntroduction:

E very first sentence:

V isuals: There are two pictures of advertisements in this article. The first one is a regular

McDonald’s ad that says, “I’m lovin’ it.”

That’s their famous slogan. The next visual uses the same slogan but shows

Ronald McDonald looking overweight and unhappy.

I think the article uses these contrasting images to show that the reality behind advertisements is not as attractive as the image companies like McDonald’s want to portray. For instance, a lot of people say that fast food makes people overweight, so maybe this article will focus on how fast food advertising is contributing to weight problems.

E nding:

S o What? Based on the features of the text, “Too Many Junk Food Ads,” I can conclude that this

42

article will express strong opinions against the amount of junk food ads, like

McDonald’s ads, that companies use to promote unhealthy food. Personally, I think it is

only fair for companies to be able to freely advertise, and it is up to the consumer to

make wise and healthy choices, regardless of the number or type of ads they see.

Say: After I look at the title, headings and visuals, I read the article, paying special attention to the introduction, the ending (or conclusion) and the topic sentences (or every first sentence of each paragraph). There is a lot of information about the big idea of the article to be found in each of those places.

Read aloud the whole article (below) to the class.

Guided:

(For guided practice, give scholars two examples – one for which you provide the observation, while partners discuss a possible conclusion, and one for which scholars must provide both the observation AND the conclusion. Scholars should work collaboratively on the first example. For the second example, ask scholars to work alone to make an observation and draw a conclusion, then collaborate with a partner to compare and revise answers. Examples of observations and conclusions are given, below. Finally, ask scholars to work in pairs to add to or revise the “So What?” section of their notes and to add a one to two sentence personal observation.)

Feature

T itle:

H eading(s):

I ntroduction:

Observation

In the introduction, the author includes the startling fact that 12 million kids struggle with their weight. Then, the author asks why advertisers “bombard” or attack kids with their enticing ads for junk food.

E very first sentence:

V

E isuals: nding:

S o What?

When I read through each of the first sentences of the paragraphs, I see that studies have been conducted to determine the type and impact of advertising on children. For example, children between the ages of 8-12 see the most advertising for junk food.

Conclusion

The author wants me to see a link between the problem with childhood obesity and junk food advertisement. I say this because by asking the question about advertisers’ behavior, he implies that they are somehow responsible for the problem he describes in the ”hook” or surprising statistic in the introduction.

I think the author might want me to see the link between the age of the kids who are seeing the advertisements and the bigger moral issue he presents. If young kids are the ones seeing a ton of junk food advertisements, they may not have the know-how to challenge what they see.

43

Monitor scholars’ work during guided practice. Assist those scholars who struggle to move from observation to conclusion. Identify two or three pairs who have arrived at strong answers to highlight during the review. Develop a sense of which scholars will need your attention during independent practice.

Independent:

During independent practice, ask scholars to complete THIEVES for a second article (or section/chapter in a nonfiction book that includes numerous text features) on their own. Circulate to help scholars as they work. Below is an article called “Warning!

Check Your Eggs!” that you might use during independent work or could use for homework (and ask that scholars repeat the same exercise). Make sure to reinforce a

7:2 ratio of minutes spent reading to minutes spent writing. This will help ensure that scholars spend ample time in text. Clearly communicate to them when and for how long during independent practice (2 minutes at a time) they should be writing.

Share/Closing: During the share, while you assess for scholars’ mastery of THIEVES (and diagnose their ability to summarize the text), allow scholars some time to offer their personal reactions to the “So What?” section. We want to develop scholars’ reader response lenses and critical thinking skills. Perhaps after reading a particular article, some scholars will be “awakened” while others think the main idea is hogwash! Allow scholars an opportunity to share their opinions with the whole class.

Homework: Assign scholars another article or section from their independent nonfiction text to read and deconstruct using THIEVES.

44

March 30, 2007

Time For Kids

Too Many Junk Food Ads!

Results of a new study are in!

BY VICKIE AN

More than 12 million kids in the United States struggle with weight problems. So why are advertisers still bombarding kids with commercials for sugary snacks and greasy fast foods?

Health officials have been saying for years that kids see way too many junk food ads on television.

On Wednesday, a study released by a health research group called the Kaiser Family Foundation showed the numbers behind those warnings.

What's the Beef?

The study was the largest ever to be conducted on food ads aimed at kids. Researchers observed 13 television networks over a period of five months. Nearly 9,000 commercials were reviewed.

Of the food ads studied, researchers found that 34 percent were for candy and snacks. Another 28 percent were for cereal, and 10 percent were for fast food. Only a small percentage of commercials were for dairy products and fruit juices. And how many were for fresh fruits and veggies? Says the foundation, none.

The findings are troubling to health officials. Especially since it is believed that these ads lead to poor eating habits. The more junk food kids eat, the higher their risk for obesity. Obesity can lead to serious health problems, including heart disease, stroke, Type 2 diabetes, cancer and high blood pressure.

"The vast majority of foods that kids see advertised on television today are for products that nutritionists would tell us they need to be eating less of, not more of," said Vicky Rideout of the Kaiser

Family Foundation.

Children ages 8-12 were found to see the most TV food ads. They watch about 7,600 of them a year.

Teens see about 6,000 food ads a year, and children ages 2-7 see about 4,400 a year.

Finding the Right Balance

45

In December 2005, the Institute of Medicine suggested that companies focus more of their advertising on foods that are lower in fats, salt and sugars. Several kid favorites, like

McDonald's, the Coca-Cola Co. and PepsiCo Inc., have accepted the challenge. The companies have agreed to promote healthier diets and exercise in at least half of all ads directed at kids.

Officials hope the report will be helpful to other studies examining the effect of the media on childhood obesity rates.

"We now have data that shows kids are seeing an overwhelming number of ads for unhealthy food,"

Senator Tom Harkin said. "The 'childhood obesity epidemic' isn't just a catch phrase. It's a real public health crisis."

46

August 23, 2010

Time For Kids

Warning! Check Your Eggs!

More than half a billion eggs are recalled after being tied to a nationwide salmonella outbreak.

BY ANDREA DELBANCO

Egg eaters, beware. More than half a billion eggs have been pulled off of grocery store shelves across the country after a recall began on August 13. The tainted eggs are linked to an outbreak of salmonella poisoning. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates the number of related illnesses at 1,300, and believes that number could continue to grow.

The cause of the outbreak is not yet known, but many of the infected eggs have been linked to two farms in Iowa,

Wright County Egg and Hillandale Farms. The farms share suppliers of chicken and feed. Tainted eggs were distributed in several states, including California, Illinois, Missouri,

Colorado, Nebraska, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Iowa.

What is Salmonella?

Salmonella, a harmful bacteria, is often carried by birds and reptiles. The bacteria can also be found in water, soil, raw meats and eggs. It can be on both the outside and inside of eggs that appear to be normal. If the eggs are eaten raw or undercooked, it can cause illness.

NIRMALNEDU MAJUMDAR —AP

Wright County Egg, near Galt, Iowa, is one of the distributors linked to the outbreak.

Eating food infected with salmonella can make people sick.

It can even be deadly. The most common symptoms of salmonella infection are diarrhea, abdominal cramps and fever. Babies and the elderly are most affected.

How To Stay Safe

The FDA oversees safety inspections of shell eggs. After the tainted egg outbreak, Margaret Hamburg, chief of the Food and Drug Administration, said the agency must do more to prevent such outbreaks, rather than contain them after they start. "We need better abilities and authorities to put in place these preventive controls and hold companies accountable," says Hamburg.

While the FDA works to ensure safety nationally, there are important steps you can take to ensure your own safety. Check your cartons to be sure the eggs in your refrigerator aren't affected by the recall. And always cook your eggs thoroughly before eating them, since high temperatures can kill harmful bacteria. Reject runny yolks at home and at restaurants. Go to here for a list of recalled egg brands, and to learn more.

47

T

Feature itle:

H eading(s):

I ntroduction:

Observation

E very first sentence:

V

E isuals: nding:

S o What?

Conclusion

48

Sample Lesson: Main Idea (Adding Up the Big Ideas Into One)

Teaching Point: Good readers know where to look to find the big ideas of a nonfiction text and can synthesize and summarize them (in their own words) into one main idea.

AIM: SWBAT conclude the main idea of a nonfiction text by “adding up” its topic

sentences into a summary.

Criteria for success (You may choose to explicitly share these during your mini-lesson

OR imply them during your think aloud):

After applying THIEVES and reading the article, write down initial ideas in the “So

What?” category about the main idea.

“Add up” each of the topic sentences

Decide whether each of the topic sentences is relevant. (Is it just a “hook” or part of the main idea?)

Paraphrase the topic sentences and synthesize them with initial “So What?” ideas to create a summary of the text.

Materials:

Copies and/or a means of projecting “Warning! Check Your Eggs!”

Visual Anchor: Topic Sentence Addition

I-Think Journals

Scholars’ nonfiction independent books or whole-class article/excerpt

Homework

Agenda:

1.

Do Now – Quick Summary

2.

Mini lesson – Main Idea Math?

3.

Guided – Add it Up

4.

Independent – Times Two

5.

Share – The Solution Is

6.

Homework

Connection/Hook:

Say: Yesterday, we spent time practicing the THIEVES strategy to locate important information in nonfiction texts using their text features. Look at the article you read yesterday (during independent practice or for homework) and your THIEVES notes.

(For this lesson, the sample is: “Warning! Check Your Eggs!”)

49

Say: Yesterday, I told you that we would focus more on the “So What?” section of your

THIEVES notes.

Quick share: Allow 3-4 scholars to share their “So What?” section from their THIEVES notes aloud.

Say: It’s good to hear your initial ideas about the main idea of the article and your personal reactions. A little later in class, we’ll use some of your thoughts about the main idea of the article in our lesson.

Mini Lesson:

Say: The “So What?” section of the THIEVES strategy is the most important section, because it’s where we present all of the information we’ve “taken away” from our observations of the text features and our reading in a few short sentences. When you take a lot of information and condense it into something smaller, it’s called summarizing. The smaller condensed version is called a summary. A good summary includes only the important information from a text and leaves out a lot of the details.

Even though you’ve practiced summarizing before, we’re going to spend a bit more time on it, because it’s actually one of the toughest skills to master.

In future lessons, we’ll talk about how to develop your personal reactions for the “So

What?” section of THIEVES, but that is not our focus today.

Today, I’m going to show you a fun way to write a summary using a strategy called Sum

It Up. The “Sum” stands for summary, but it also stands for adding. To do this, we’re going to take a closer look at topic sentences or the first “E” (every first sentence) in

THIEVES and “add it all up” to make a great summary. (Language for the mini-lesson,

above, adapted directly from Nonfiction Reading Power by Adrienne Gear, p. 99)

One key place to look for big ideas in a nonfiction text is in the topic sentences. As writers, you know that the topic sentence should always connect to the thesis – or big idea – statement of your paper. In that same way, we can look at an author’s topic sentences to get a sense of which information is important enough to include in a summary. Of course, not every topic sentence is important to include in a summary.

That’s because sometimes author use topic sentences simply to “hook in” a reader.

They might ask an interesting question or make a shocking or catchy statement to draw in readers. Also, there may be more details that need to be included beyond what is included in topic sentences. However, topic sentences are a very helpful place to start.

I took all of the topic sentences from “Warning! Check Your Eggs!” and listed them here. My next step is to “add” them all up, until I have the “Sum” or beginning of a strong summary (project or post the following list as a visual anchor):

50

1.

Egg eaters, beware.

2.

The cause of the outbreak is not yet known, but many of the infected eggs have been linked to two farms in Iowa, Wright County Egg and Hillandale Farms.

3.

Salmonella, a harmful bacteria, is often carried by birds and reptiles.

4.

Eating food infected with salmonella can make people sick.

5.

The FDA oversees safety inspections of shell eggs.

6.

While the FDA works to ensure safety nationally, there are important steps you can take to ensure your own safety.

If I read through the topic sentences listed like this, I see I have the beginning of a summary, because some key information is included. However, it’s incomplete. I need to spend some time deciding how relevant each of the topic sentences is, what other information needs to be added, and how I can put the topic sentences into my own words. (Model for scholars how you think through the first three topic sentences, assess their relevance, and paraphrase them. When you paraphrase, show scholars how to add in information and how to simplify when necessary, while not changing the tone of the sentence/passage. Record or reveal pre-written thoughts in an I-Think journal. See example, below.)

Topic Sentence Addition

Topic Sentence

1.

Egg eaters, beware.

2.

The cause of the outbreak is not yet known, but many of the infected eggs have been linked to two farms in

Iowa, Wright County Egg and Hillandale Farms.

3.

Salmonella, a harmful bacteria, is often carried by birds and reptiles.

Relevant?

This seems more like a hook, or something to scare the reader.

But it also shows me that there is a danger that people who eat eggs need to be aware of.

Based on this sentence, I don’t know which outbreak is being referred to. However, since I have read the passage, I know it’s about salmonella, so I’ll add that in. I’m not sure that the names of the farms are truly important to the brief summary, so I’ll remove them.

This topic sentence could practically be added in to the summary as it is, except that the reference to reptiles doesn’t connect to why eating eggs is dangerous for consumers.

Reptiles lay eggs, of course, but most people don’t buy them in stores and eat them. This article is about the dangers of the eggs we eat. So, I’ll make the connection more clear and leave out the reference to reptiles.

Paraphrase

People who regularly eat eggs need to be cautious.

An outbreak of salmonella has been linked to infected eggs from two farms in Iowa.

Salmonella is a harmful bacteria that is often carried by birds and, thus, their eggs.

51