Security, DPT and war

Democratic Peace Theory (DPT)

Overview o Mearsheimer (1990), Chan (1984), Russett (1993)

Strand one: institutional constraints o Audience costs/public opinion: Doyle (1986), Fearon (1994), Schultz (1999) o Institutions (checks and balances – executive selection, political competition, and pluralism of the foreign policy decision-making process): Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman

(1992), Bueno de Mesquita, et al. (1999)

Strand two: democratic norms/culture o Schweller (1992)

Critiques o Layne (1994), Mansfield and Snyder (1995), Zakaria (1997), Rosato (2003)

War

Causes of war o Overview: Huntington (1993), Stepan (2000), Levy (1998), Levy (1988), Sagan (1990),

Fearon (1995), Powell (1996, 2006), Kirshner (2000), Hassner (2003) o Security dilemma/offense-defense balance: Schelling (1960, 1963), Schelling and

Lessons from 9/11 o Kaufmann (2004), Hemmer (2007)

Civil War

Halerpin (1961), Jervis (1978), Van Evera (1984), Van Evera (1999) o Critiques: Betts (1999), Levy (1984), Glaser and Kaufman (1998)

Civil war – causes o Collier (2000), Fearon and Laitin (2003), Fearon (2005), Miguel, et al. (2004)

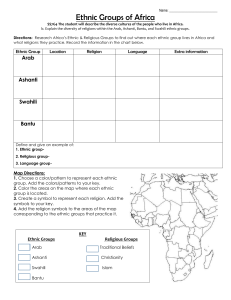

Nationalism/ethnic conflict o Classics: Anderson (1983), Gellner (1983), Hobsbawm (1992) o Nationalism and war: Van Evera (1994)

Rationalist: Fearon (1994), Lake and Rothchild (1996), de Figueiredo and

Weingast (1994), Gagnon (1994/5), Mueller (2000),

Symbolic politics : Horowitz (1985), Kaufmann (2006)

Genocide o Valentino (2000), Fujii (2008)

What to do? o Wittman (1979), Finnemore (1996), Kuperman (2008), Betts (1994), Kaufmann (1996),

Luttwak (1999), Toft (2010)

Democratic Peace Theory (DPT)

Overview o Mearsheimer (1990)

Democratic peace – domestic political factors are the principal determinant of peace; the presence of liberal democracies in the international system will help produce a stable order; democracies do not go to war against other democracies – why?

(1) authoritarian leaders are more likely to go to war because they are not accountable to their publics, which carry the main burdens of war, while democratic leaders are

(2) citizens of liberal democracies respect popular democratic rights, even of those in other states, so they won’t wage war against other democracies (democracy seen as most legitimate) o Chan (1984)

Whether freedom promotes peace depends on how the researcher operationalizes the dependent variable – whether war, violence, conflict, all wars, inter-state wars only, etc.

If the analysis focuses on dyadic relationships and excludes extra-systemic wars

(like colonial or imperialist ones), democratic states appear more pacific than non-democratic ones, though the finding is not statistically significant o Russett (1993)

Democracies rarely fight each other because they have other means of resolving conflicts between them and they perceive that democracies should not fight each other; by this reasoning, the more democracies there are, the fewer potential adversaries we and other democracies will have and the wider the zone of peace

Prior to WWI, feeling of common liberal and democratic values played a part in moderating power conflicts between the US and Britain (over

Venezuela) and Britain and France (Fashoda Crisis); but did not with US and Germany

Up until WWII, empirical fact of little war between democracies could be obscured by the predominance of authoritarian states

After WWII, democracy seen more as a binding principle of Cold War coalition against communism than as a force actively promoting peace among democracies themselves

By 1970s, increasing number of democracies with little war or even serious threats of war

Problems with overreaching claims: democracies are not more peaceful in general and democracies do sometimes fight (depends on definition/threshold of “fight”)

Democratically organized political systems in general operate under restraints that make them more peaceful in their relations with other democracies; democracies less likely to use lethal violence toward other democracies than toward autocratically governed states or than autocratically governed states are toward each other

Looks at interstate war with more than 1000 battle deaths

Cultural/normative model

In relations with other states, decision-makers try to follow the same norms of conflict resolution as have been developed within their domestic political processes; they will expect decision-makers in other states likewise to follow the same norms of conflict resolution as have been developed within their domestic political processes o Violent conflict between democracies are rare because the decision-makers resolve conflicts by compromise, so will follow norms of peaceful conflict resolution; more stable democracies

more democratic norms govern behavior o Violent conflict between non-democracies and between democracies and non-democracies more frequent because in non-democracies decision-makers use violence and threat of violence to resolve conflict as part of domestic political processes (so other states expect this); democratic norms can be more easily exploited to force concessions, so to avoid this, democracies may adopt non-democratic norms in dealing with non-democracies

Structural/institutional model

Violent conflict between democracies rare because democracies constrained by checks and balances, division of power, and need for public debate to enlist widespread support (slows decisions to use violence); leaders of other states perceive democratic leaders as constrained, so they expect slow-action and thus do not fear surprise attacks

Violent conflict between non-democracies and between democracies and non-democracies more frequent because leaders of nondemocracies are not constrained like democratic leaders, which means they can move to use force more quickly; thus, leaders of other states may initiate violence rather than risking surprise attacks o Moreover, non-democracies (knowing democracies constrained) may press for greater concessions, but this may cause democracies to initiate conflict rather than give in to these concessions

Strand one: institutional constraints o Audience costs/public opinion o Doyle (1986)

Schumpeter (1942): liberal pacifism; capitalism and democracy are forces for peace (antithetical to imperialism); capitalism produces an unwarlike disposition because its populace is “democratized, individualized, rationalized”; when free trade prevails, no class gains from forcible expansion (only war profiteers will gain)

Kant (1795): liberal internationalism; once aggressive interests of absolutist monarchies are tamed and the habit of respect for individual rights engrained by republican government, people will hesitate to embark on war because it will bring the miseries of war down upon themselves (this doesn’t hold where people are not citizens – the head of state owns the state, so he can go to war without sacrificing anything himself); liberal states are morally integrated – as culture grows and men gradually move toward greater agreement on principles,

leads to mutual understanding and peace (liberal states assume non-liberal states, which do not rest on free consent, are not just)

Constitutional, international, and cosmopolitan (meaning ties of international commerce and free trade) sources connect the characteristics of liberal polities and economies with sustained liberal peace “a separate peace exists among liberal states” (which doesn’t extend to non-liberal states – here, there is still insecurity caused by anarchy) o Fearon (1994)

Audience costs are an important factor enabling states to learn about an opponent’s willingness to use force in a dispute; at a price, audience costs make escalation in a crisis an informative although noisy signal of a state’s true intentions by creating the possibility that leaders on one or both sides will become locked into their position and so will be unable to back down due to unfavorable domestic political consequences; a crisis always has a unique horizon – a level of escalation after which neither side will back down because both are certainly locked in, making war inevitable; before the horizon is reached, the fear of facing an opponent who may become committed to war puts pressure on states to settle

Regardless of the initial conditions, the state more sensitive to audience costs is always less likely to back down in disputes that become public contests (greater domestic cost for escalating more informative signal of escalation, so less escalation required to convey intentions)

Stronger domestic audiences may make democracies better able to signal intentions and credibly to commit to courses of action in foreign policy than non-democracies, features that might help ameliorate the security dilemma between democratic states

If relative capabilities or interests can be assessed by leaders prior to a crisis and if they also determine the outcome, then we should not observe crises between rational opponents: If rational, the weaker or observably less interested state should simply concede the issues without offering public, costly resistance.

Crises would occur only when the disadvantaged side irrationally forgets its inferiority before challenging or choosing to resist a challenge.

Possessing military strength or a manifestly strong foreign policy interest does deter challenges in the model, but if a challenge occurs nonetheless, neither the balance of forces nor the balance of interests has any direct effect on the probability that one side rather than the other will back down once both have escalated; which side backs down in a crisis should be determined by relative audience costs and by unobservable, privately known elements of states’ capabilities and resolves o Schultz (1999)

Two arguments in the literature:

Institutional constraints (below) – suggests democratic leaders generally face higher political costs for waging war; as a result, when a state is challenged by a democracy, the target has reason to doubt that the challenge will actually be carried out and targeted states should be more likely to resist when threatened by a democracy than when threatened by a state that is not similarly constrained

Informational perspective (above) – suggests democratic governments are better able to reveal their true preferences in a crisis; relative to non-democracies, they are less likely to engage in bluffing behavior, meaning that the threats they do make are more likely to be genuine; as a result, the target of a threat made by a democracy should be less inclined to resist or further escalate the crisis

Crisis bargaining literature: without complete information (asymmetrical distribution), it is difficult to identify/agree on mutually beneficial bargain

Democracy promotes emergence of multiple information sources by permitting opposition parties to compete openly for the support of the electorate, so it faces constraints on its ability to conceal or misrepresent its preferences for war and peace (institutionalized competition constrains a government to be more selective about resorting to threats while at the same time improving the effectiveness of the threats it does make)

Finds that the likelihood of reciprocation is lower when the initiating state is a democracy than when it is not (consistent with informational perspective)

Suggests democratic institutions help reveal information about a state’s preferences in a credible manner (threats more likely to be genuine) o Institutions (checks and balances – executive selection, political competition, and pluralism of the foreign policy decision-making process) o Lake (1992)

Democracies not only fight wars against each other less often, but also tend to win the wars that they do fight

This is because autocratic states typically earn rents at the expense of their societies (“state rent-seeking”) and thus possess an imperialist bias and tend to be more expansionist (hence, more war-prone)

Democracies are constrained by their societies from earning rents, so they devote greater absolute resources to security, enjoy greater societal support for their policies, and tend to form overwhelming counter-coalitions against expansionist autocracies ( propensity for victory in war) o Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman (1992)

Democratic institutions facilitate the mobilization of opposition, making it easier for challengers to unseat a government that undertakes costly or failed policies; war is thus an especially risky prospect for democratic leaders, who may find themselves in early retirement if things go badly; non-democratic leaders, in contrast, are better insulated from such risks o Bueno de Mesquita, et al. (1999)

In addition to common claims, there are additional regularities as part of DPT – as two examples, democracies win a disproportionate share of their wars and their costs are lower

Assume leaders motivated by a desire to keep their job

Model based on political institutions: because the winning coalition size increases in democracies as compared to non-democracies, holding budget constant, each member’s share of private goods decreases; this makes public policy benefits loom larger in utility assessment of members of winning coalition in democracies; democratic leaders thus must be especially concerned about policy failure and will make a larger effort to succeed in disputes (with small

winning coalitions, giving benefits to a few protects leaders from being deposed); this implies democratic leaders pick and choose their conflicts carefully

Democrats are thus more likely to win wars than autocrats because they try hard and spend resources on the war and, because they fear failure, they avoid contests that they do not think they can win

Democrats thus inclined to negotiate with each other rather than fight because they anticipate that war will result in spending a lot of resources in a risky situation where neither side is disproportionately advantaged by greater effort o Democratic leaders generally attack only if they anticipate victory (or at least have a substantial probability of victory)

Autocrats, since they reserve resources for domestic uses to satisfy key constituents, do not try as hard in war (defeat will not greatly affect their prospects of political survival at home)

Because democrats use their resources for the war effort rather than reserve them to reward backers, they are generally able, given their selection criteria for fighting, to overwhelm adversaries, which results in short and relatively less costly wars (against non-democratic opponents)

Strand two: democratic norms/culture o The culture, perceptions, and practices that permit compromise and the peaceful resolution of conflicts without the threat of violence within countries come to apply across national boundaries toward other democratic countries (democratic states develop positive perceptions of other democracies – instead of war, use peaceful competition, persuasion, and compromise) o Schweller (1992)

Preventive war – wars that are motivated by the fear that one’s military power and potential are declining relative to that of a rising adversary; can be for offensive (take advantage of closing window of opportunity) or defensive reasons (prevent opening of window of vulnerability); “wars of anticipation,” so their justification rests only upon the inherently un-provable assumptions of human foresight

Gilpin (1981), Levy (1987): power shifts seen as key, so preventive action is often most attractive response for a declining dominant power

Power shift is neither a necessary nor sufficient condition for war, so why do some power shifts result in preventive war while others do not? When looking at power shifts between states of roughly equal strength:

Only non-democratic regimes wage preventive wars against rising opponents; declining democratic states do not exercise this option

When the challenger is an authoritarian state, declining democratic leaders attempt to form counterbalancing alliances

When the challenger is another democratic state, declining democratic leaders seek accommodation

A model of liberal democratic domestic structures as determinants of decisions about war and peace must include as model-based features the relative power resources of the states involved (Kant: public opinion inhibits democratic state actors from initiating wars expected to be of great risk and cost)

That is, must go beyond the “billiard-ball model of state behavior” – the structural-realist assumption that all states react similarly to external pressures is incorrect

Citizens of governments founded on the enlightenment principles of individual liberty and the pursuit of happiness are naturally repulsed by the unethical and immoral aspects of preventive war, as it implies the unprovoked slaughter of countless soldiers/civilians on the mere assumption that future safety requires it

That is, the strength of public opinion in democratic states generates a complex of factors that lessens the motivation to enter into preventive war; pacific effect of public opinion, though, is somewhat contingent on the expectation that the war will be costly

Critiques o Democracies have gone to war very often against non-democratic regimes, democratic citizens can become very nationalistic o International and domestic norms often induced from observed patterns of behavior in international conflicts; empirically, there are many cases where democratic states followed policies at variance with the norms argument (imperialism – wars were about subjugation, not self-preservation) o Layne (1994)

Where DPT and realism depart: DPT holds that changes within states can transform nature of international politics, while realism takes the view that even if states change internally, the structure of the international political system remains the same (systemic structural constraints means that similarly placed states will act similarly, regardless of domestic political systems)

Why institutional constraints do not explain DPT: (1) if democratic public opinion had this effect, democracies would be peaceful in their relations with all states (lives lost and money spent will be the same), (2) checks and balances are not exclusive to democracies

Do norms explain it? Uses process tracing on case studies of “near-misses” where democratic states had opportunity and reason to fight, but did not

One example that realism is better than DPT in explaining why war avoided: Ruhr Crisis of 1923 (France and Germany) – disconfirms DPT; after WWI, both public and elites in France perceived Germany as dangerous threat to France’s security and great power status, even though Weimar Germany was a democracy; what mattered was

Germany’s latent power, not its domestic political structure; driven by strategic concerns, not mutual respect based on democratic norms/culture, French used military power coercively to defend

Versailles system, but Germany didn’t have military capabilities so pulled back from the brink by passively resisting (rather than entrust security to hope that Germany’s democratic institutions would mitigate geopolitical consequences flowing from underlying disparity between

German and French power)

Other problems with DPT:

N is actually smaller than purported (few democracies earlier in history, possibility of any particular dyad being in war is small, not all dyads are

created equal – war relatively infrequent outcome and dyads are significant only if they represent a case with a real possibility of war)

WWI is a glaring problem for the theory – in terms of foreign policy,

Wilhelmine Germany was actually a democracy o Mansfield and Snyder (1995)

Democratic peace may hold in the long run, but not in the short

Countries do not become mature democracies overnight – more typically, they go through a rocky transitional period in which they become more aggressive and war-prone and do fight wars with democratic states

Democratizing states (or states going through reversals) more likely to fight wars than mature democracies or stable autocracies

See this for almost every great power – combination of incipient democratization and material resources of a great power produced nationalism, defiance abroad, and major war

How democratization/autocratization causes war

Huntington (1968): institutional weaknesses exist in these regimes; typical problem of political development is the gap between high levels of political participation and weak integrative institutions to reconcile the multiplicity of contending claims (if newly democratizing state doesn’t have strong parties, independent courts, a free press, etc., there is no reason to expect mass politics to produce the same impact on foreign policy as it does in mature democracies) o Elites often only haphazardly accountable to electorate o Difficult to form stable coalitions with coherent platforms and sufficient support to stay in power short-run thinking and reckless policy-making, which can lead to war

After breakup of autocratic regime, elite groups are left over and many have interest in war/empire (because the gains from war accrue to small or specific groups), but must compete with rising democratic forces – both sides try to mobilize mass allies (often through nationalist appeals), but once mobilized, these allies are difficult to control, and war may result o Elites typically react by using logrolling, squaring the circle

(integrating opposites), and prestige strategies (shore up prestige at home by seeking victories abroad), which breed recklessness

Note: Oneal, et al. (2003) find no evidence that democratization increases the danger of military conflict (instead add to the theories by finding, among other things, that there are benefits of economic interdependence as well as joint membership in intergovernmental organizations) o Zakaria (1997)

Rise of illiberal democracy – while democracy is flourishing, constitutional liberalism is not (democratically elected regimes routinely ignoring constitutional limits on their power and depriving citizens of basic rights and freedoms)

Forces of democracy are not necessarily the forces of ethnic harmony or peace

– without a background in constitutional liberalism, the introduction of democracy in divided societies has fomented nationalism, ethnic conflict, and even war

Example: the spate of elections immediately after the collapse of communism were won in the USSR and Yugoslavia by nationalist separatists and resulted in the breakup of those countries; the rapid secessions, without guarantees, institutions, or political power for many minorities living within the new countries caused spirals of rebellion, repression, and in places like Bosnia and Georgia, war

The democratic peace is actually the liberal peace; it has little to do with democracy o Rosato (2003)

Normative logic: norm externalization and mutual trust and respect explain why democracies rarely fight one another

Flaws: (1) democracies do not reliably externalize their domestic norms of conflict resolution nor do they (2) generally treat each other with trust and respect when their interests clash o Imperialism of Europe’s great powers between 1815-1975 shows democracies waging wars for reasons other than selfdefense and the inculcation of liberal values – these were wars in which, by definition, the colonial powers sought to perpetuate or re-impose autocratic rule; it is not simply that liberal norms only mattered a little, it is that they have often made no difference at all o Democracies tend to act like any other pair of states – bargaining hard, issuing threats, and if they believe it is warranted, using military force; we see this in American interventions to destabilize fellow democracies in the developing world during the Cold War (commitment to contain communism overwhelmed respect for fellow democracies); examples: Chile in 1973 (coup to overthrow Allende), Nicaragua in 1984 (supported Somoza dynasty rather than Sandinistas)

So, we see that democratic trust and respect often subordinated to security and economic interests

Attempted revision: perception is important

Problem: we are unlikely to be able to predict how states will perceive one another’s regime type (only know after the fact); within a regime, often divided opinions

Institutional logic: democratic institutions and processes make leaders accountable to a wide range of social groups that may, in a variety of circumstances, oppose war (possible mechanisms: public constraint, group constraint, slow mobilization, surprise attack, information)

Flaws: accountability does not affect democratic leaders any more than it affects their autocratic counterparts, pacific publics or antiwar groups rarely constrain policy-makers’ decisions for war (this should make democracies more peaceful in their relations with all types of states, but

it doesn’t; leaders can cultivate nationalism to counter this), democracies are not actually slow to mobilize nor incapable of launching surprise attacks, and open political competition provides no guarantee that a state will be able to reveal its level of resolve in a crisis

(rally around the flag effect during crises occurs on both sides; democratic leaders can also lead, rather than follow, public opinion during crises by controlling what information reaches the public)

War

Causes of war: overview o Huntington (1993): “The Clash of Civilizations?”

Dominant source of conflict will be cultural

Civilizations, not states/nation-states, are the key units

A civilization is a cultural entity, the highest cultural grouping of people and the broadest level of cultural identity people have short of what distinguishes humans from other species

Differences among civilizations are basic – history, language, culture, tradition, and most importantly, religion; these differences are more fundamental and less easily compromised than among political ideologies or economic ones

“The Velvet Curtain of culture has replaced the Iron Curtain of ideology as the most significant dividing line in Europe.”

Gives primacy of place to Christianity as the distinctive positive influence in the making of Western civilization

Western culture’s key contribution has been the separation of church and state, something that he sees as foreign to the world’s other major religious systems

Due to the growing importance of “kin cultures” and “civilizational fault-line conflicts,” the world’s religious civilizations are increasingly unitary and changeresistant

Democracy (1) emerged first within Western civilization and (2) other great religious civilizations of the world lack the unique bundle of cultural characteristics necessary to support Western-style democracy o Critiques: Stepan (2000)

Islam: implication is the “free elections trap” – elections in predominantly

Islamic countries will lead to fundamentalist majorities who will use their electoral freedom to end democracy, but this is empirically incorrect (in the world’s three largest Islamic countries – Indonesia, Bangladesh, Pakistan – there is no support for this)

Example: Indonesia – Suharto’s 32-year rule from 1965-98 was a military authoritarian regime with sultanistic dimensions, but in 1999 election campaign, Wahid (became president) created the PKB and argued for religious pluralism, no fundamentalist party had a significant following after Suharto and the two most fundamental parties, the PBB and PK, polled only 2 percent and 1 percent of the popular vote

Eastern Orthodoxy: church is national organization, so the state often plays a major role in its finances and appointments; but, look at Greece: since the fall of the junta, the democratic task (after 1974) required not the disestablishment of the church, but the elimination of any nondemocratic domains of church power that restricted democratic politics (as the two military juntas, one in 1967 and

one in 1973, had arranged the appointment of a new archbishop to head the church) o Levy (1998)

Theories of the causes of war: systemic-level (typical positions – relative v. absolute gains, etc.)

Realism: key division in realist literature on war is between balance of power theory and power transition, or hegemonic, theory (which downplays importance of anarchy – at a dyadic level, this is the power preponderance hypothesis)

Liberalism – economic interdependence: trade generates economic advantages for both parties and the anticipation that war will disrupt trade and result in a loss/reduction of welfare gains deters leaders from war against trading partners o But, there are numerous historical cases of trade between enemies during wartime need to consider domestic variables

Theories of the causes of war: societal level

DPT variations (and see below)

Theories of the causes of war: individual level

Assumptions: external and internal structures and social forces are not translated directly into foreign policy choices; key decision-makers vary in their definitions of state interests, assessments of threats to those interests, and/or beliefs as to the optimum strategies to achieve those interests; differences in the content of actors’ belief systems, in the psychological processes through which they acquire information and make judgments and decisions, and in their personalities and emotional states are important intervening variables in explaining observed variation in state behaviors with respect to issues of war and peace o Example: role of elites’ misperceptions o Central theme is that decision-making is characterized by

“bounded rationality” o Levy (1988)

Domestic politics and war

DPT [see earlier in outline]

Economic structure

Marxist-Leninist theory – focuses on economic structure as key independent variable; inequitable distribution of wealth in capitalist societies generates overproduction, inadequate domestic investment opportunities, and generally stagnant economies expansionist and imperialist policies abroad, competition for access to markets, investment opportunities, and raw materials, and ultimately to wars between capitalist states; also generate war economies and high levels of military spending as replacement markets to absorb excess capital, which can lead to war through arms races, international tensions, and a conflict spiral; capitalist states may also initiate wars against socialist states in a desperate attempt to prevent the further deterioration of their own positions o Note: not much evidence in support of this

Liberal theory – free trade promotes economic efficiency and prosperity, which in turn promotes peace

Nationalism and public opinion

Rally around the flag effect

Public opinion can constrain political elites, but at the same time, political elites can actively manipulate it for their own purposes

“Diversionary” or “scapegoat” hypothesis o Tendency of peoples in a wide range of circumstances to support assertive national policies which appear to enhance the power and prestige of the state, which may lead decisionmakers, under certain conditions, to embark on aggressive foreign policies and sometimes even war as a means of increasing or maintaining their domestic support (use foreign war to divert attention away from internal problems – ingroup/out-group conflict) o Sagan (1990)

Origins of the Pacific War – Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was rational;

Japanese government found itself in a desperate position in which starting a war that all agreed was unlikely to end in victory was the best alternative

(probability of victory low, costs of defeat extremely high, yet launched attack anyway)

Origins are best understood as a mutual failure of deterrence: Japanese wanted to expand into Southeast Asia, but sought to do so while deterring American intervention in support of the European colonial powers; US attempted to prevent Japanese expansion, but sought to do so without precipitating war in the Pacific

Severe miscalculations

Example: Japan decided to move into southern Indochina because they believed it would not result in an American oil embargo because

Washington “knew well enough” that such an embargo would force

Japan to attack the Dutch East Indies (to obtain oil from somewhere else); US officials knew about the impending Japanese occupation of southern Indochina and debate revolved around whether an oil embargo would provoke a Japanese attack on the European colonies – and yet, despite warnings, US stopped all shipments of oil to Japan in

1941 (provocation because it gave the Japanese immense time pressures because any hope of a naval victory for Japan would soon be gone – why did the US do this?) o Once provocative move taken, it may appear more dangerous to change course than to stick to the unintended policy (so as not to appear like appeasement/giving in to Japanese aggression) – this may explain why Roosevelt opposed moving the fleet from Pearl Harbor to the West Coast in 1940

Negotiations stalled, so Japan made a plan to “destroy the will of the US” to fight a prolonged war – knew complete victory impossible, but sought quick victories in the Pacific to set up a defensive barrier and persuade the US that a painful war of attrition was simply not worth fighting

Deterrence theory emphasizes twin requirements of capability and credibility for successful deterrence – military capabilities must be sufficient to threaten to inflict unacceptable costs on an enemy and the threats must have sufficient credibility (execution of that threat must appear probable enough to make the risks of attacking unacceptable)

This case shows how policy of deterrence can fail even if the force capabilities are robust and threats are credible

Deterrence failed because the costs of not going to war were considered even higher than the anticipated “unacceptable” costs of war to Japan o Fearon (1995)

Wanted wars are Pareto-efficient – they occur when no negotiated settlements exist that both sides would prefer to the gamble of military conflict; unwanted wars are a bigger puzzle, but solvable

Problem: war is inefficient ex-post (as long as both sides suffer some costs for fighting, war is always inefficient – both sides would have been better off if they could have achieved the same final resolution without suffering the costs)

Rationalist explanations for war try to explain this inefficiency by explaining why states don’t reach an ex-ante agreement that avoids the costs states know they will pay ex-post if they go to war

None of the principal rationalist arguments advanced in the literature holds up as an explanation because none addresses or adequately resolves the central puzzle, namely, that war is costly and risky, so rational states should have incentives to locate negotiated settlements that all would prefer to the gamble of war – the common flaw is that rationalist explanations fail either to address or adequately explain what prevents leaders from reaching pre-war bargains that would avoid the costs and risks of fighting

Existing rationalist causes for war:

Anarchy: Waltz (1959) o War occurs because there is nothing to prevent it – no supranational authority to make and enforce law

Rational preventive war o If a declining power expects it might be attacked by a rising power in the future, preventive war in the present may be rational

Expected benefits > expected costs: Bueno de Mesquita (1981) o Problem for these three explanations: given some relatively weak assumptions, there always exists a set of negotiated settlements that both sides prefer to fighting – ex-post inefficiency of war opens up an ex-ante bargaining range – what explains this?

Rational miscalculation about relative power: Blainey (1988) o Explains disagreements about relative power as a consequence of human irrationality (emotional commitments/nationalism)

Rational miscalculation due to lack of information (example: Japanese miscalculated US willingness to fight a long war)

o Problem for these two explanations: what prevents states from sharing private information about factors that might affect the course of battle?

So what explains why states fail to agree on outcome in bargaining range?

Rational leaders may be unable to locate a mutually preferable negotiated settlement due to private information about relative capabilities or resolve and incentives to misrepresent such information o While states always have incentives to locate a peaceful bargain cheaper than war, they also always have incentives to do well in bargaining

Rationally led states may be unable to arrange a settlement that both would prefer to war due to commitment problems, situations in which mutually preferable bargains are unattainable because one or more states would have an incentive to renege on the terms o Note: first-strike and offensive advantages exacerbate other causes of war by narrowing the bargaining range

States may be unable to locate a peaceful settlement both prefer due to

issue indivisibilities o Powell (1996)

Stability and distribution of power – probability of war is a function of the disparity between the status quo distribution of territory and the distribution of power

If disparity small, division of benefits expected from use of force is approximately the same as the existing status quo distribution, so gains to using force are too small to outweigh costs of fighting (probability of war is zero)

If disparity large, then at least one state is willing to use force to overturn the status quo (as disparity grows, probability of war increases) o These results contradict the expectations of both the balance of power (probability of war smallest when power evenly distributed) and preponderance of power schools (probability of war smallest when distribution of power highly skewed – preponderance of power most stable)

Must control for status quo in assessing the relationship between the probability of war and the distribution of power o Powell (2006)

Most informational explanations of war begin with a bargaining model in which there would be no fighting under complete information

But, asymmetric information does not provide a convincing account of prolonged conflict, like in civil wars (Fearon)

It also ignores the possibility that there might be fighting even when states have complete information

The bargaining range is not empty even if the dispute concerns an indivisible issue, the state is risk-acceptant, or there are first-strike or offensive advantages

– the problem is that states cannot commit themselves to abiding by agreements

Commitment problems most important – states can have full information and still fight due to large shifts in the distribution of power; this can lead to bargaining breakdowns and war o Kirshner (2000)

Fearon’s (1995) central claim is that the existence of private information is the most important cause of rational war

Problems with Fearon’s assumptions (too constraining): in many cases war will occur even if the problem of private information resolved

Fearon assumes issue indivisibilities can be resolved through issue linkages and side payments – his framework cannot address

“meaningful territory” like Jerusalem; wars are fought over political goals, so the costs and benefits of fighting are largely political, so the range of mutually acceptable deals may be smaller than a purely materialist calculation would imply (example: even if states want to avoid the costs of war, it might be politically risky to accept side payments how much money could Milosevic have offered Clinton to avoid the bombing?)

Fearon ignores risk acceptant leaders (sees leaders as risk averse or risk neutral, with Hitler as possible exception) – but, in some instances, the existence of risk acceptant behavior can be a cause of war

Fearon ignores indirect utility (glory, prestige, reputation, domestic political benefits)

Problem with private information (that one side has, but not the other): often, information may be “unknowable” until it happens, so experts may fundamentally disagree over the probable costs and benefits of war o Hassner (2003)

Importance of indivisibilities – sacred places seen as inherently indivisible and this perception impedes efforts to resolve disputes over them

Indivisible because they are cohesive, have unambiguous boundaries, and cannot be exchanged or substituted for another good or issue (nonfungibility)

Sacred space has two parameters that indicate the attachment of a group to a sacred site and the price it attaches to maintenance or change in its status quo: centrality (Basilica of St. Peter in Rome for Catholics) and exclusivity (example:

Mount Athos in Greece or Meteora for Greek Orthodox followers)

The more central the site to the identity of the religious community, the more likely they will take action in response to challengers to the integrity of the site

The more exclusive the site, the greater the risk that foreign presence or conduct will be interpreted as an offensive act

Because of indivisibility problems, conflict over sacred space cannot be resolved by negotiation or compromise

Realism: offense-defense balance theory/security dilemma (consequence of anarchy) o Schelling (1960, 1963), Schelling and Halperin (1961)

Arms control theory

Essential feature of arms control is the recognition of the common interest, of the possibility of reciprocation and cooperation even between potential enemies with respect to their military establishments

Arms control rests on the theory that wars can occur because states have failed to realize the cooperation which their interests actually entail o Hostile states almost always have important interests of military policy in common (although one side can win a war, both could lose in the sense of there having been at least one if not several outcomes that would have been mutually preferred to fighting) o Arms control and security policy are not opposed to each other

Thus, there is a danger of inadvertent war and so reassurances are necessary to show the adversary that the state will refrain from attacking if the adversary will too

“Reciprocal fear of surprise attack”

Even if both sides prefer peace to war, war could result due to this reciprocal fear

Thus, there is an enormous advantage in the event that war occurs to the side that starts it (first-strike advantage) o See this as the most troublesome aspect of “today’s strategic weapons” o Rational for a state to attack even if it was peaceful because the alternative to attacking would be seen, not as peace, but as being attacked o Thus, a state’s efforts to deter the adversary or protect itself in case of war would make war more likely ( security dilemma) o Also, if a state appears weak, war may occur, so a state must show that it will not back down in the face of threats o Jervis (1978)

Even if states satisfied with status quo and have a common goal, difficult to reach it (example: Stag Hunt – incentives to defect)

One state may become dissatisfied with status quo at future date

Due to self-help, for protection, states seek to control resources outside their territory or in “buffer zones,” but this can alarm others

Security dilemma – many of the means by which a state tries to increase its security decrease the security of others o The fear of being exploited drives the security dilemma o This implies that, all else equal, a world of small states feels the effects of anarchy more than a world of large states. However, if one state is invulnerable, it can exploit others, so the security dilemma remains. o The best situation is “passive invulnerability,” where defending is easier than attacking or there is mutual deterrence

Notes that vulnerability is subjective and depends on decision-makers, but that if offensive and defensive

weapons differ, it is possible for a state to make itself more secure without making others less secure

Measure = does state have to spend more or less than one dollar on defensive forces to offset each dollar spent by other side on forces used to attack

High costs of war and gains from cooperation will lessen security dilemma competitive bargaining

Typology: (1) off/def distinguishable?, (2) off/def advantage? o Doubly dangerous = no, off advantage; security dilemma = no, def advantage; no security dilemma, but maybe aggression = yes, off advantage; doubly stable = yes, def advantage o Van Evera (1984)

Example supporting Jervis (1978) is WWI

The cult of the offensive was one principal cause of WWI – without the assumption that the offense was strong, the problems leading to WWI would have been less acute/risky

Before WWI, belief that “attack is the best defense”; Schlieffen Plan = rapid attacks (thought conquest was easy); believed in “windows” of opportunity and vulnerability – future vulnerability need to act decisively in the present

When offense is strong: states adopt more aggressive foreign policies, first strike advantage increases, “windows” of opportunity and vulnerability widen, states adopt more competitive diplomacy, and increase political and military secrecy o Thus, the plans in WWI made sense for an offense-dominated world – the problem was the assumption was just wrong o Van Evera (1999)

Realist argument – sees international anarchy as the permissive cause of war o But, focus is more on preferences and perceptions – not objective measures – of power o Biased perceptions of power depend on four factors: manipulation by elites, self-serving bureaucracies, militarism, and nationalism (if factors present, war more likely)

The preferences and relative power of social groups are the underlying independent variables, while perceptions and ideas often serve as an intervening process that widens and deepens the domestic influence of those groups

These ideas about misperceptions (depending on preferences/power of domestic groups who mislead/coerce) are more liberal than realist

Important footnote: “Most of the important contributing causes of war are neither necessary nor sufficient.”

War is more likely when conquest is easy or, more often than not, is

mistakenly perceived to be easy

Hypotheses for when war is more likely: o When states fall prey to false optimism about its outcome

o When the advantage lies with the first side to mobilize or attack because this leads countries to conceal their grievances, capabilities, and plans (illusion of this advantage is more common than actually having a decisive advantage) o When the relative power of states fluctuates sharply – that is, when windows of opportunity and vulnerability are large (giving incentives for preventive or preemptive action)

Critique (Betts (1999)): a cause of strategy is not the same as a cause of war (Hitler, for example, is widely seen to have wanted war from the beginning, so his strategic decisions were about when, not whether, there would be a war) o When resources are cumulative – that is, when the control of resources enables a state to protect or acquire other resources

Offers a “master theory”: offense-defense theory o This is the “most powerful and useful realist theory on the causes of war”

Critiques of offense-defense balance o Betts (1999)

Offense-defense theory has been overwhelmingly influenced by the frame of reference that developed around nuclear weapons and the application of deterrence theorems to WWI

Authors often confuse the question by shifting the defense of O-D balance to the level of political outcomes – the effects of operational advantages on national decisions about whether to initiate war o Example: nuclear O-D balance often cited as defense dominant, but no effective defenses against nuclear attack exist – this claim is based on mutual vulnerability preventing leaders from starting engagement; this makes calling both the WWI and Cold

War balance defensive confusing – for the first, it’s defensive in combat interactions, but for the second, in political effects

Van Evera’s (1999) offense-defense balance variable lumps together a large number of variables, including things like geography and popularity of regimes – how to aggregate and measure?

There is a need to focus on political stakes, especially because internal, civil wars have recently been much more common than international wars

International wars are about which countries control which territories while intra-national wars are about which groups get to constitute the state

Internal wars differ from the conventional terms of reference by which

O-D theory developed – when contending groups are divided by ideology, religion, or ethnicity, they are often intermingled and combat is not carried out on one front with conventional lines of operation (the front is everywhere, especially if see irregular or guerrilla warfare)

Van Evera (1999) believes that modern guerrilla war has defended many countries and conquered none and is thus a defensive form of warfare, this is not true in reality – look at communist guerillas in

Greece or the Contras in Nicaragua – they were attacking native governments (offensive)

o Levy (1984)

Problematic assumption: The hypothesis is that the likelihood of war increases when military technology favors the offense, but this depends on a crucial, and questionable, assumption that decision-makers correctly perceive the balance.

Problematic typical definitions:

Example: military tends to prepare for previous war, not next one

Ease of territorial conquest – tactics offensive sometimes, defensive others (ex: Schlieffen Plan – hold against Russia to move against France)

Characteristics of armaments – only hold for land warfare, no aggregation, nothing about doctrine

Resources needed by offense to overcome defense – imprecise definitions make this hard to define

Incentive to strike first – compounding variables, like geography

Problematic empirical validity: judged retrospectively (we don’t know leaders’ perceptions at the time) and still much divergence of opinion

Example: after siege of Constantinople in 1453 where offense was prominent, better fortifications were created but also increased mobility from adopting Turkish Janissary tactics throughout Europe o Glaser and Kaufman (1998)

How to fix O-D balance definitional problem

Define as ratio of the cost of the forces that the attacker requires to take territory to the cost of the defender’s forces (gives a link between a state’s power and its ability to perform military missions)

Assume states act optimally, study dyads, and have broad conception, including: technology, geography, force size, nationalism, and cumulative resources

(Nationalism? This definition has the same problems.)

Lessons from 9/11 o Kaufmann (2004)

Bush administration’s arguments to the public to generate support for preventive war shows successful “threat inflation” (examples: Saddam as undeterrable, Saddam as terrorist, existence of WMDs, chemical and biological threats); the “marketplace of ideas” failed – why?

Democratic political systems may be inherently vulnerable to issue manipulation by elites

Control over government’s intelligence apparatus selective publicizing

White House seen as having credibility

Countervailing institutions – like the press – failed to check the ability of those in power to control foreign policy debate

Shock of 9/11 atrocities created crisis atmosphere that may have reduced public skepticism o Hemmer (2007)

Joffe: 9/11 as a lightning bolt rather than an earthquake – the attacks did not radically reshape the contours of international politics, but shined a bright but fleeting light on the already-existing landscape; it ushered in an ideational change in American foreign policy rather than a structural change (not a change in global balance of power)

Lessons learned:

Increased threat of devastating surprise attacks ( universal war on terror)

Need to counter threats actively, to go on the offense and not rely on defense and deterrence o These two lessons led to war in Iraq (alternative explanations: unipolarity or domestic politics)

Civil War

Civil war – causes o Collier (2000)

Economic perspective on causes of civil war (uses statistical analysis of civil wars from 1965-1999) – risk related to dependence upon primary commodity exports, low national income, slow growth, rapid population growth, ethnic dominance, and diasporas; things like inequality, lack of democracy, and ethnic and religious divisions have had little systematic effect on risk (maybe because they make organization more difficult)

Primary commodity exports are the most lootable of all economic activities, which leads to opportunities for predatory rebellion

Low incomes advantage the rebels because governments take in less tax revenue, which reduces the capacity of the government to spend on defense

Slow growth and rapid population growth assist rebel recruitment

While a discourse of grievance appeals to many as an explanation of civil wars,

Collier advances the following: civil wars occur where rebel organizations are financially viable (able to raise revenue, like the FARC in Colombia which earns a huge amount of money from drugs and kidnapping)

Rebellions are not the ultimate protest movements, but the ultimate manifestation of organized crime (use grievance discourse simply because they need to motivate their recruits)

What to do?

If accept grievance account, try to promote democracy or equality or redraw boundaries – this is counter-productive

Instead, need to make it harder for rebel organizations to get established (conflict prevention)

Post-conflict, though, the organizations have been established, so will need to figure out a way to address the subjective grievances of the parties to the conflict o Fearon and Laitin (2003)

Common assumptions are wrong:

The prevalence of civil war in the 1990s was not due to the end of the

Cold War and the associated changes in the international system

A greater degree of ethnic or religious diversity does not make a country more prone to civil war on its own

One cannot predict where a civil war will break out by looking for where ethnic or other broad political grievances are strongest

Instead, the main factors determining the variation in civil violence are conditions that favor insurgency – a technology of military conflict characterized by small, lightly armed bands practicing guerrilla warfare from rural base areas

Financially, organizationally, and politically weak central governments render insurgency more feasible and attractive due to weak local policing or inept and corrupt counterinsurgency practices

Like Collier and Hoeffler (2000), argue that economic variables matter, but mainly because they proxy for state administrative, military, and police capabilities o Fearon (2005)

Collier and Hoeffler (2000): the extent of primary commodity exports is the strongest single influence on the risk of conflict – this creates better opportunities to finance rebel groups and so enables rebellion

This result is quite fragile (example: they use five year intervals rather than annual measurements and have much missing data – author uses country-years and multiply imputes)

Agrees that better rebel funding opportunities probably do imply a greater risk of civil war, other things equal, but that there is little reason to expect primary commodity exports as a percentage of GDP to be a good measure of financing rebel potential

Instead, cash crops or oil production are critical – oil exporters are more prone to civil war because they tend to have weaker state institutions than other countries with the same per capita income o Miguel, et al. (2004)

See economic variables as key determinants of civil war

But, many economic variables are endogenous to civil war; omitted variable bias exists in these studies as well

Instrumental variable approach – IV = exogenous variation in vegetation (highly correlated with rainfall) for GDP growth; weather shocks are plausible instrument for GDP growth in economies that largely rely on rain-fed agriculture

sub-Saharan Africa – economic growth is strongly negatively related to the incidence of civil conflict (1983-1999)

Other variables like per capita GDP, political instability, mountainous terrain, oil exporter status, ethnic diversity, and democracy do not display a robust relationship with the incidence of civil wars in Africa

What is the explanation for economic growth?

A major negative income shock is likely to make the life of a guerilla relatively more attractive (example: with threshold of 25 battle deaths per year, a five percentage negative growth shock raises the likelihood of a civil war by over one-third)

Nationalism and ethnic conflict o Haas (1986)

Nationalism as rationalization – that is, nationalism may well be a rational response to certain social upheavals and frustrations, not a throwback to barbarism o Anderson (1983)

“Imagined communities” – a nation is an imagined political community; it is imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign

It is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, yet in the minds of each lives the image of communion

The nation is imagined as limited because even the largest of them has finite boundaries, beyond which lie other nations o That is, size, communication by way of shared symbols, and exclusiveness mark the nation as different from other political constructs

What makes the shrunken, national imaginings of recent history generate such huge sacrifices?

The answer lies in the cultural roots of nationalism.

Religion has the ability to turn fatality into continuity – this was affected by developments in 18 th century Western Europe

Secularization (religion declined due to explorations of the non-

European world and due to print capitalism – this demoted the sacred language; idea of “divine right of kings” faded)

Disenchantment with the world o Thus, needed to recreate the ideas of community by means of a secular transformation of fatality into continuity – the idea of a nation is very well suited for this purpose because the nation looms out of the immemorial past and stretches into the limitless future

The concept of time changed: from simultaneity along time homogenous empty time

The novel and newspaper (confidence that everyone was reading the same paper, even if couldn’t actually know all of them) provided the technical means for representing the nation – they created a remarkable confidence of community in anonymity

Effect of print capitalism – consolidated and standardized the different vernaculars spoken by the masses in order to gain profits (developed unified communication systems)

So, the interaction between capitalism, print, and the fatality of linguistic diversity were crucial factors in creating the nation o “imagined communities” were linguistically unified fraternities of equals

Critiques: unclear terms like “imagined” and “sovereign”; exaggerates the importance of cultural nationalism while underestimating the political dimension o Gellner (1983)

Nationalism is a distinctly industrial principle of social evolution and organization; the nation-state is the sole legitimate form of political organization within the global trend toward industrial societies

It is primarily a political principle that holds that the political and national unit should be congruent

It is a theory of political legitimacy (ethnic boundaries should not cut across political ones)

Type of national identification that prevails in a given society depends on three things: (1) distribution of political power: upward-mobility v. hereditary or quasi-hereditary, (2) easy access to “high culture” of literate and sophisticated communication via a system of public education v. vertically segmented groups each attached to a local “low culture,” and (3) ethnic homogeneity v. ethnic heterogeneity, as defined by language

Nationalism expresses the societal thrust toward homogeneous perception and homogenous social organization and behavior

Nationalism is not the resurgence of submerged primordial longings for ethnic community; it is a consequence of the “objective need” for industrial rationality o Hobsbawm (1992)

Nationalism is a principle which holds that the political and national unit should be congruent (but nations are not older than the 18 th century and there is no satisfactory subjective or objective criteria by which to define them)

Nations do not make states and nationalisms, but the other way around

The function of nationalism in state-formation must be viewed from both above and below: the modernizing state needs greater uniformity and literacy but inhabitants also begin to demand that their rulers should be co-cultural and not alien o But, national consciousness develops unevenly between social groupings and regions

Phases of national movement in 19 th century: cultural, literary, and folklore national idea/political campaigning mass support of nationalist programs

Nation = state = people

“Proto-nationalism” – the consciousness of belonging to a lasting political entity (this made the eventual task of nationalism easier)

The national question arises at a particular historical conjuncture of political, technological, and social change

Transformation of nationalism, 1870-1914: abandoned the threshold principle, ethnicity and language, and sharp shift to the political right of nation and flag; nationalism did not overcome socialism (seen in 1914 by the working classes going off to war instead of refusing to vote war bonds, sabotaging war reparations, or resorting to armed insurrection) – the same individuals could be loyal socialists and patriotic at the same time o Van Evera (1994)

Nationalism is a political movement in which individual members give their primary loyalty to their own ethnic or national community and these ethnic or national communities desire their own independent state

What is the relationship between nationalism and war?

Four primary attributes of a nationalist movement determine whether it has a large or small potential to produce violence:

Movement’s political status – is statehood attained or unattained?

Movement’s stance toward national diaspora (if it has one) – does it accept continued separation or seek to incorporate into national state?

Movement’s stance toward other nations – respect or deny other nationalities’ right to national independence?

Movement’s treatment of own minorities – respected or abused? o These can be used to create a nationalism “danger-scale,” expressing the level of danger posed by a given nationalism, or by the spread of nationalism in a given region; if all four attributes are benign, the nationalism poses little danger of war, and may even bolster peace

How do we know if these attributes are benign or malignant?

Structural factors – geography, demography (domestic balance of power, density of intermingling), military setting (internal borders?)

Political-environmental factors – how have neighbors behaved? past crimes? how did they act after the crimes?

Perceptual factors – nationalist self-images and images of others

(myths? scapegoats? legitimacy of regime? scope of demands?)

Sees Western Europe as having “satisfied” nationalisms because they have already gained states; Eastern European nationalisms, however, are risky because of stateless nationalisms (predicts a substantial amount of violence over the next several decades) o Lake and Rothchild (1996)

Ethnic conflict is not caused directly by inter-group differences, "ancient hatreds" and centuries-old feuds, or the stresses of modern life within a global economy; moreover, ethnic passions, long bottled up by repressive communist regimes, were not simply uncorked by the end of the Cold War

Ethnic conflict is caused by the “fear of the future, lived through the past”

Intense ethnic conflict is most often caused by collective fears of the future; as groups begin to fear for their safety, dangerous and difficultto-resolve strategic dilemmas arise that contain within them the potential for tremendous violence; as information failures, problems of credible commitment (arise whenever the balance of ethnic power shifts), and the security dilemma take hold, groups become apprehensive, the state weakens (which further exacerbates information problems), and conflict becomes more likely o Strategic interactions between groups create the unstable social foundations from which ethnic conflict arises

State weakness allows ethnic activists and political entrepreneurs, operating within groups, to build upon these fears of insecurity and polarize society

“Non-rational” factors like political memories and emotions also magnify these anxieties, driving groups further apart

What to do?

Ethnic conflict can be contained, but it cannot be entirely resolved.

Effective management seeks to reassure minority groups of both their physical security and, because it is often a harbinger of future threats, their cultural security; demonstrations of respect, power-sharing, elections engineered to produce the interdependence of groups, and the establishment of regional autonomy and federalism are important

confidence-building measures that, by promoting the rights and positions of minority groups, mitigate the strategic dilemmas that produce violence

International intervention may also be necessary and appropriate to protect minorities against their worst fears, but its effectiveness is limited; non-coercive interventions can raise the costs of purely ethnic appeals and induce groups to abide by international norms; coercive interventions can help bring warring parties to the bargaining table and enforce the resulting terms; mediation can facilitate agreement and implementation

Key issue in all interventions, especially in instances of external coercion, is the credibility of the international commitment – external interventions that the warring parties fear will soon fade may be worse than no intervention at all o Kaufmann (2006)

Existing theories:

Rational choice – claim that extreme ethnic violence (war and genocide) can be explained either as the result of information failures and commitment problems or as the utility-maximizing strategy of predatory elites (Fearon (1994), Lake and Rothchild (1996)); alternative is that predatory elites are the key cause of ethnic war and genocide because they provoke violence as a way of maintain power and misleading their supporters into thinking the other side is to blame for the violence (de

Figueiredo and Weingast (1994))

Symbolic politics (Kaufmann) – asserts that such violence is driven by hostile ethnic myths and an emotionally driven symbolic politics based on those myths that popularizes predatory policies (media important here); hostile myths produce emotion-laden symbols that make mass hostility easy for chauvinist elites to provoke and make extremist policies popular ethnic security dilemma in which growing extremism of leadership on at least one side results in radicalization of leadership on the other(s) spiral of escalation o Horowitz (1985): the sources of ethnic conflict reside, above all, in the struggle for relative group worth (Croat is said to have asked a Serb: “Why should I be a minority in your state if you can be a minority in mine?”) o The appeal of myths, of course, depends on whether there are certain preconditions, like if the group fears that its existence is threatened and whether there is political opportunity, meaning space to mobilize without repression and territorial concentration

Milosevic: symbolism of battle of Kosovo Field in 1389 used to conflated Serbs’ modern Albanian rivals with their historical Ottoman enemies to promote feelings of hostility and fear and to justify on mytho-historical grounds his policy of domination over the Kosovo

Albanians

Tests these models in the cases of Sudan's civil war and Rwanda's genocide and show that the rationalist models are incorrect: neither case can be understood

as resulting from information failures, commitment problems, or rational power-conserving elite strategies

In both cases ethnic mythologies and fears made predatory policies so popular that leaders had little choice but to embrace them by playing up associated ethnic symbols, even though these policies led to the leaders' downfalls o Example is Sudan: northern myths insist on Islamic identity that requires application of sharia law to the entire country, whereas southern myths cast northerners as would-be enslavers and prescribes resistance to northern domination o Gagnon (1994/5)

Follows from de Figueiredo and Weingast (1994): predatory elites provoke violence as a way to maintain power and mislead their supporters into thinking the other side is to blame for the violence

Ethnic nationalism and international conflict – case of Serbia

Violent conflict is not caused by ethnic sentiments, nor external security concerns, but by the dynamics of within-group conflict

Realism is wrong here – sees conflictual behavior in the name of ethnic nationalism as a response to external threats to the state (or ethnic group)

Idea of ancient ethnic hatreds is wrong – Yugoslavia never saw the kind of religious wars seen in Western and Central Europe and Croats and Serbs never fought before this century

Domestic situation key: internal dynamics – violent conflict in former Yugoslavia was purposeful and rational strategy planned by those most threatened by changes to structure of economic and political power, advocated by reformists within ruling Serbian community party

Domestic bases of power crucial to elites; persuasion is most effective and least costly means of influence in domestic politics; if elites threatened, can shift focus of political debate away from issues like the economy toward other issues structured in cultural or ethnic terms in order to appeal to the interest of the majority in non-economic terms; creating an image of threat places the interest of the group above the interest of individuals; because looking at domestic setting, information

and control over information play a vital role; elites will tend to define the relevant collective in ethnic terms when past political participation has been so defined; larger the threat to ruling elite, more willing it is to take measures which preserve its position in the short term but bring high costs in the longer term – it discounts future costs; external costs also key – strategy most likely if external costs that affect the status quo elites’ domestic power position are minimal

Violent conflict along ethnic cleavages provoked by elites in order to create a domestic political context where ethnicity is the only politically relevant identity; constructs the individual interest of the broader population in terms of the threat of the community defined in ethnic terms; this strategy is a response by ruling elites to shifts in the structure of domestic political and economic power – by constructing individual interest in terms of threat to the group, endangered elites can fend off domestic challengers who seek to mobilize the population

against the status quo, and can better position themselves to deal with future challenges o Mueller (2000)

Here, again, political authorities are key, but in a different way – they let it happen, though it might not be for their own political gain (question: then why

let it happen?)

Ethnic war essentially does not exist – it is not motivated by ancient hatreds nor by frenzies whipped up by demagogic politicians and the media

Ethnic war more closely resembles non-ethnic warfare because it is waged by small groups of combatants, groups that purport to fight and kill in the name of some larger entity; violent conflicts in Croatia and Bosnia were spawned by small bands of opportunistic marauders (un-policed thugs – examples: (1)

Serbian prison inmates were released for the war effort and (2) Arkan’s Tigers, which were essentially mercenaries; some essentially became warlords over their territories) recruited by political leaders and operating under their general guidance

Comparison case is Rwanda: Interahamwe were militia bands that had been created and trained by Hutu extremists, but they had their genesis in soccer fan clubs where they recruited jobless young men; as the genocide began, more poor people including street boys and homeless joined – they essentially had the blessings of a form of authority to take revenge on socially powerful people as long as they were on the wrong side of the political fence; here, criminals also released from jail and looting prospects remained large

The mechanisms of violence in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda is remarkably banal – rather than reflecting deep historic passions or hatreds, the violence was a result of a situation in which common, opportunistic, sadistic, and often distinctly non-ideological marauders were recruited and permitted free rein by political authorities

Genocide o Valentino (2000)

Existing explanations for mass killing:

Social cleavages – presence of deep divisions between groups within society, which polarize society, lead to intergroup conflict, and dehumanization of other

National crises – provide critical spark; scapegoat theory; political opportunity theory

Regime type – democratic forms of government associated with lower levels of mass killing

“Strategic” perspective – the search for the causes of mass killings should begin with the specific goals and strategies of high political and military leadership, not with broad social or political structures – the active support of a large portion of the public is usually not required to carry out mass killing (passivity or indifference typically is); regardless of whether the general public supports or opposes mass killing, civilians almost never play a major role in the killing itself

Types of mass killings:

o Dispossessive – ideological-political (leaders with radical agendas, like communists, or ethnic/nationalist/religious, like

Nazis); territorial, like colonial enlargement o Coercive – counter-guerrilla, terroristic, imperial

What to do? This perspective suggests the most effective way to prevent mass killing is to deal with the specific motivations and conditions which prompt leaders to consider it (example: intervention to bring about change in leadership) o Fujii (2008)

How do ordinary people come to commit genocide against their neighbors?

(uses narrative data from Rwanda)

Ethnicity-based approaches cannot explain the different pathways that lead to mass violence or the different forms that participation takes over time and place.

In Rwanda, different processes and mechanisms led some to join in the carnage while others resisted.

Granovetter's (1985) concept of “social embeddedness” – social ties and immediate social context better explain the processes through which ordinary people came to commit mass murder in Rwanda; leaders used family ties to target male relatives for recruitment into the killing groups, which were responsible for carrying out the genocide; ties among members of the killing groups helped to initiate reluctant or hesitant members into committing violence with the group; ties of friendship attenuated murderous actions, leading killers to help save Tutsi in specific contexts

Which ties became salient (to their group, Tutsi victims, or local leaders) depended on the context – in the presence of the killing group or authority(ies), low-level participants (“joiners”) tended to go along with the violence, but alone, joiners often made different choices, sometimes acting to save Tutsis instead of killing them

What to do? o Wittman (1979)

Agreement to end a war must make both sides better off – the expected utility of continuing the war must be less than the expected utility of the settlement

During the course of a war, each country is constantly reassessing its probability of winning in response to new information regarding the progress of the war

The better one side does, the more it will demand in negotiations (an increase in the probability of country Y losing means an increase in the probability of country X winning and thus country X’s expected utility from continuing the war increases X’s minimal demand increases) o Argues differently than balance of power and preponderance of power schools – there is no relationship between the probability of winning and the probability of war; war and peace are simply substitute methods of achieving an end (if one side is more likely to win at war, its peaceful demands increase)

A reduction in hostilities (unilaterally or bilaterally) in year t may prolong the war and make a settlement in year (t + 1) less likely – a nation may be heavily committed to fighting a war but realize that a reduction in its efforts will result in only a slight decrease in the probability of winning, so the expected utility

increases even though the probability of winning decreases opposition’s probability of winning increases increases expected utility from continuation o Finnemore (1996)

Constructing norms of humanitarian intervention – there is really no advantage to the intervener in most post-1989 cases like Somalia (as neo-realists would argue) and often justification is on humanitarian and not democratization grounds (as neo-liberals would argue)

Justification is key because states are drawing on and articulating shared values/expectations held by other decision-makers and publics in other states