Supplementary Appendix 8 (docx 39K)

advertisement

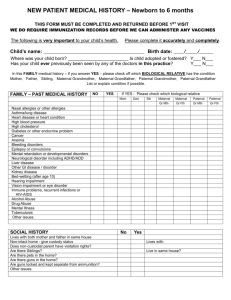

Appendix 8. Shared environment assumptions In this appendix, we discuss if the way we specified the shared environment might have led us to draw the wrong conclusion regarding the general genetic factor. When modeling monozygotic and dizygotic twins, it is reasonable to assume that both individuals within a given pair grow up in the same family. We extended the ordinary twin model to pairs of different types of siblings, and assumed that full siblings and maternal half-siblings shared all of the common environment whereas paternal half-siblings shared none of it. It can be noted that other authors have used other approaches that rest on other assumptions to test for shared environmental effects (38). Results showed that regardless of how we modeled the shared environment, it played a diminishingly small role for the covariation among the disorders and thus our conclusion that the data support a general genetic factor of psychopathology when using national registers remains valid. How should the shared environment be parameterized based on annual tax records? Although we assumed that the common environment was shared completely for full and maternal half-siblings and not at all for paternal half-siblings, there may be other ways to parameterize it. For example, to the extent that one assumes that the shared environment consists of growing up in the same household, it could be quantified based on annual tax records, similar to what have been used by Kendler and colleagues. (38) Specifically, these tax records annually identify the building each person is registered to, such as a house or apartment complex. To the extent that separated parents do not live in the same building, children who live with different parents will have different values in these records. Of course, alike our original shared environment assumption, this index is obviously not a description of reality; even though children might be registered as living in the same or different households, this could be because of tax and/or equality issues and is therefore not a perfect indicator for how much time they have spent together. Nevertheless, it provides some insight into the siblings’ average living situation. Because these records exist from 1968 and on, the respective pairs with complete information on this variable included 267,714 pairs of full siblings, 28,434 pairs of maternal half-siblings, and 29,950 pairs of paternal half-siblings. To estimate time spent in the same household for each sibling pair, we examined how many years both individuals in each pair were registered to the same building according to the tax records. We counted from the birth of the second sibling up till the year the first sibling turned 18. For example, if there was an age difference of four between two siblings, then they could live in the same household for up the 14 years (i.e., 18 - 4). We then counted how many of those years they were registered as living in the same building. For example, if two siblings with an age difference of four were registered to the same building for 12 years, then we estimated that they lived together 86 percent of the time (i.e., 12/14). Thus, this index ranged from zero (never registered as living in the same building) to one (always registered to the same building). As can be seen in the figures below outlining the respective distributions of time registered as living in the same building, full and maternal half-siblings by and large grew up in the same household, supporting our assumption that they shared all of the common environment. The distribution based on paternal half-siblings, on the other hand, was largely bimodal, indicating that about half lived in different buildings, but that the other half were registered as living in the same building throughout childhood and adolescence. To the extent that the shared environment is assumed to reflect time spent in the same household, this violates our assumption that they do not share any of the common environment. 10000 15000 0 0 5000 Frequency 150000 Time living together: Maternal half siblings 50000 Frequency 250000 Time living together: Full siblings 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 Fraction together 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 Fraction together 8000 4000 0 Frequency 12000 Time living together: Paternal half siblings 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 Fraction together Although this parameterization of shared environment is based on a set of assumptions that might not be entirely valid, as noted above, in the next section, we explored what happened to the shared environment when we parameterized it in a number of different ways, including based on the tax records. We provide arguments that the shared environment is of negligible importance, regardless of what assumptions we make about it. Does the original model that omitted the shared environment fit the data well? Before fitting additional models, note that our original solution included two genetic and one non-shared environment factor, as indicated by several dimensionality indices. To the extent that the shared environment influenced the data, this model, which omitted the shared environment, ought to fit poorly. However, by all measures, the original model fit the data very well (RMSEA = .001; CFI = .99). This implies that the shared environment probably did not influence our variables particularly much. Fit statistics, however, pertain to the entire model. Another way to explore whether the shared environment mattered is to examine the residual cross-sibling, cross-trait correlations separately for maternal and paternal half-siblings. Regardless of whether our original parameterization or the one based on tax records is the most optimal, we would expect the shared environment to have a greater influence on maternal compared to paternal half-siblings. Thus, to the extent that the shared environment influenced the observed correlations, omitting to model this component ought to lead to larger residuals for the maternal half-siblings. In the figure below, we plotted the absolute cross-sibling, cross-trait residuals (observed minus modeled correlations) separately for maternal and paternal half-siblings. A visual inspection suggests that there is virtually no difference in model misfit between maternal and paternal half-siblings. One way to quantify differences between distributions is to compute Cohen’s d, which expresses the difference in terms of standard deviations. Cohen’s d for the residuals between maternal and paternal halfsiblings equaled .03. Thus, even though we omitted to model the shared environment, model misfit was about the same for maternal and paternal half-siblings, indicating that the shared environment likely played a very small part. 0.00 0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08 0.10 0.12 0.14 0.16 Absolute residual cross-trait, cross-twin variances and covariances 30 20 10 Maternal half-siblings 0 10 20 30 Paternal half-siblings Alternate parameterizations of the shared environment and its subsequent influence Although our original model that omitted the shared environment appeared to fit the data very well, one may argue that our shared environment assumptions were problematic in light of the observation that a sizable proportion of paternal half-siblings were registered as living in the same building. To remedy this, we ran an additional set of Cholesky decompositions in which we parameterized the shared environment in several different ways. For each parameterization, we examined the magnitude of the first shared environment Eigen value (summarized in Table 1 below). To the extent that this value did not exceed unity, it implies that the shared environment had a diminishingly small influence on the observed overlap among the disorders. Table 1. Alternate parameterizations of the shared environment and the corresponding first Eigen value. Shared environment parameterizations Models Full C = 1 Mat C = 1 Pat C = 1 Pat = .5 Pat = 0 Pat = 1/0 Original model x x x Alternate model 1 x x Alternate model 2 x x x Alternate model 3 x x x Alternate model 4 x x x Note. C = Shared environment. Full = full siblings; Mat = Maternal half-siblings; Pat = Paternal half-siblings. Alternate model 4 is limited to participants who lived together more than 80% (C = 1) or less than 20% (C = 0) of their childhood according to tax records. First C Eigen value 0.17 0.70 0.56 0.61 0.66 First, we ran a model (alternate model 1) based on only full and maternal half-siblings because these groups both evidenced highly similar distributions of time registered as living in the same building (i.e., the vast majority of siblings from both groups were registered as living in the same building throughout childhood and adolescence). The first shared environment Eigen value based on a Cholesky decomposition was .70, that is, it did not exceed the commonly used cutoff of one (meaning that it accounted for less than one variable). This indicates that even when we relied on only full and maternal-half siblings (who by and large appeared to grow up in the same household), there was very little meaningful covariance in the shared environment matrix, supporting our decision to exclude it. Second, we ran two additional models in which we specified that the shared environment was shared at unity (alternate model 2) or at .5 (alternate model 3) among paternal half-siblings. The first shared environment Eigen values were .56 and .61, respectively. This indicates that regardless of how the shared environment was parameterized among paternal half-siblings, it did not appear to influence the observed overlap among the disorders. Third, we ran a Cholesky decomposition in which the shared environment parameterization was based on the living situation according to annual tax records (alternate model 4). We selected the full siblings (257,575 pairs) and maternal half-siblings (22,522 pairs) who were registered as living in the same building at least 80 percent of the time. We split the paternal half-siblings into two groups: those who had lived together more than 80 percent of the time (15,821 pairs), and those who had lived together less than 20 percent of the time (11,258 pairs). For the former group, we fixed the shared environment parameter at unity, and for the latter group, we fixed it at zero. Results demonstrated that the first shared environment Eigen value equaled .66. Thus, when we analyzed the subsample for which there was annual housing information and parameterized the shared environment accordingly, the shared environment still did not have a meaningful influence on the observed overlap among the disorders. Summary In this appendix, we explored a number of different ways to parameterize the shared environment. Regardless of how we analyzed the data, we did not find evidence for an appreciable effect of the shared environment on the correlational structure. Therefore, even though none of the shared environment assumptions used in the models above are probably correct, it does not seem to matter because the shared environment did not appear to influence the covariances among our variables. Thus, we believe that our conclusion that a general genetic factor underlies a large amount of the overlap among disorders in national registers is supported.