Introduction - Amerind Foundation

advertisement

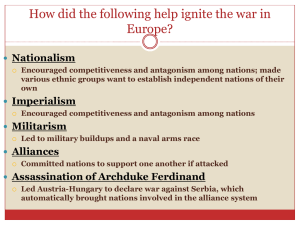

Casas Grandes I. II. III. V. VI. Titles Introduction JCGE a. Overview 1. Project Overview 2. INAH b. Excavation c. Lab Work d. Casas Grades Volumes 1. Scope 2. Importance to current and future scholars Paquime a. Architecture b. Social Structure and Ritual 1. Mounds 2. Ball Courts c. Water System and Agriculture d. Economy & Trade 1. Macaw/Turkey breeding 2. Ceramics i. Mata Ortiz connection e. Adjacent / Related Sites Current Research, Future Endeavors Concluding Thoughts I. Title IV. Opening title, credits, site overview II. Introduction Casas Grandes, also known as Paquimé, has been long recognized as one of the premier prehispanic communities in the northwest Mexico / American Southwest, yet the history of research of the area has varied greatly through time. The first European explorers in the region noted the site. Baltasar de Obregon, the chronicler of the Ibarra Expedition, described Paquimé perhaps a short time after its abandonment: B&W image of Spanish explorers observing Paquimé “…this large city…contains buildings that seemed to have been constructed by the ancient Romans. It is marvelous to look upon… …There are many houses of great size, strength, and height. They are of six and seven stories, with towers and walls like fortresses for protection and defense against the enemies who undoubtedly used to make war on its inhabitants. The houses contain large and magnificent patios paved with enormous and beautiful stones resembling jasper. There were knife-shaped stones which supported the wonderful and big pillars of heavy timbers brought from far away. The walls of the houses were whitewashed and painted in many colors and shades with pictures of the building.” Baltasar de Obregón in 1584 Over time the remains of this impressive community were reduced to tall hills of dirt. Pre Excavation imagery For 400 years after Obregon’s visit, a small number of scholars, adventurers, and others visited northwestern Chihuahua and Paquimé. Paquimé is located in the Northwest corner of Chihuahua, Mexico. It is unfortunately less known than some of the iconic sites north of the border. Minnis Clip 1 “There are certain communities in the ancient world in the borderlands of the U.S. Southwest and Northwest Mexico that were particularly important. We know many of them; Chaco Canyon, Pueblo Grande in Phoenix, Mesa Verde, the Galisteo Basin near Santa Fe. One of the ones that’s most important in late prehistory is Paquime or Casas Grandes, in Northwest Chihuahua, and it’s not as well-known as it should be, but it was exceptionally influential in the area, a great ritual, political center and economic center that lasted for a short period of time and then became a part of the dust of history until the Amerind Foundation’s Charles Di Peso started to excavate it in 1958.” Map Minnis Clip 2 “One of the unfortunate things about the location of Paquime, or Casas Grandes, is it’s sandwiched between two of the most intensively studied areas in the world.” To the north, the U.S. Southwest has long has fascinated a large number of archaeologists. Many archaeologists over more than a century have investigated hundreds of pre-Hispanic archaeological sites. They are visually impressive. The remains that have been found in these cliff dwellings and sites excite the imagination. Images of Pueblo Bonito and Chetro Ketl Perhaps this can best illustrated by Chaco Canyon, a general analogy to Casas Grandes because both were major and influential centers in the prehispanic NW/SW. Imagery of Mesoamerican Sites To the South in Mesoamerica, spectacular ruins have attracted attention for centuries. The great pyramids of the Maya that dot the jungles of Southern Mexico and the ruins of Aztec, Olmec, and Zapotec cities and monuments in Central Mexico have understandably fascinated archaeologists for centuries. Minnis Clip 3 “It’s been very important to Mexicans. The center of Mexican power and population and economic wealth is in that part of Mexico and there’s been a great deal of archaeological work done by Mexican archaeologists as well as others in Central Mexico and Southern Mexico.” Overview images of Paquimé Very few North American archaeologists have ventured south of the border to Chihuahua (or other borderland states). Most of those who have done so did not make these areas their professional focus so research continued in fits and starts. Likewise, Mexican archaeologists largely ignored the northernmost part of their country. Minnis Clip 4 “…it’s been viewed my Mexicans as a hinterland, an area of desolate deserts with no great pyramids or ancient cities. And so Northern Mexico has not gotten the attention from the United State archaeologists nor has it gotten attention for a long period of time from Mexican archaeologists.” This lack of research is unfortunate for two major reasons. First, it delayed an understanding of the unique prehispanic history of the region. As importantly, there were prehispanic relationships between Mexico and the U.S. Southwest. Understanding the prehistory of northwest Mexico, the intervening region between the Southwest and Mesoamerica, including West Mexico, is essential for detailing the nature, scope, and scale of the relationships between the three areas. These deficiencies were recognized and addressed by an archaeological project of unprecedented scale and complexity. III. Joint Casas Grandes Expedition (JCGE) Casas Grandes Volume 1 is opened; frame in book reveals video of excavation in progress Vintage Film of workers digging, sifting, and examining aspects of the site The watershed for Chihuahuan archaeology was the Joint Casas Grandes Expedition (JCGE), which conducted field work from 1958 to 1961. Conceived by Charles C. Di Peso and William Shirley Fulton, founder and patron of the Amerind Foundation, and in collaboration with the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, the expedition still remains after many decades the largest internationally collaborative archaeological project in the US-Mexican borderlands. Pan over images of Di Peso, WS Fulton, and Contreras Di Peso was responsible for the excavations, analyses, and publication of the results. INAH’s representative, Eduardo Contreras, mapped the site and oversaw the herculean task of stabilization and reconstruction of the excavated structures. Along with the Snaketown project in Arizona the Joint Casas Grandes Expedition was one of the two largest and best-organized archeological projects of its day in the northwest Mexico / American Southwest region. Vintage Film clip of field workers Di Peso and Contreras were supported by a large and diverse staff and colleagues, including in the field, in the laboratory, and during preparation of the publication which would be titled Casas Grandes: A Fallen Trading Center of Gran Chichimeca and published in 1974 by the Amerind. Animated image and pan of 1st 3 volumes (hands opening book), then the last 5 The eight volumes published on the site are arranged for different audiences. The first three volumes are well–illustrated overviews that both professionals and the public could read. The last five volumes are dense data presentation for professionals. In addition, the illustrator for the project report, Alice Wesche, produced a delightful children’s book about ancient Paquimé. A Series of pans over illustrations from the volumes The Amerind Foundation also prepared a film strip useable in schools. Pan over a still of the Gran Chichimeca filmstrip Perhaps most important of all, the JCGE increased the interest and pride in Paquimé among the people of Chihuahua that also set the foundation for archaeological tourism in the region. During the excavation students from nearby Casas Grandes and Colonia Juarez were led on tours of the site. Vintage Film clips of students at site All archaeologists would still do well by emulating the Joint Casas Grandes Expedition’s public outreach example. Video Pan over the site as it is now, exterior of Museum INAH continued its commitment to Paquimé and the archaeology of northwestern Chihuahua. More archaeologists are employed in Chihuahua, new archaeological sites are being stabilized and opening to the public, and a world-class museum has been opened at the now designated World Heritage site of Paquimé. Shots of crew toasting a successful project. IV. Paquimé The Joint Casas Grandes Expedition shed new light on prehispanic Northwest Mexico. Minnis Clip 5 “Casas Grandes was a very spectacular place with massive architecture and incredible artifacts; a ton and a half of shell, hundreds of skeletons of macaws, turkeys, hundreds of turkeys which oddly enough weren’t eaten but were used as sacrifices for rituals, ritual mounds, a water distribution system that is unrivaled in the New World. It just an amazing place and that was all shown by Di Peso’s work, and Contreras’ work at Casas Grandes.” a. Architecture Aerial photo pan, fading to several elevation pans of the walls The tall dirt hills are the remains of massive adobe room blocks, some several stories tall. The 1000 to 2000 rooms at the site housed between 2,000 and 5,000 people during the Medio period, A.D. 1200 to the late 1400s. The thick, almost concrete-like walls were made of rammed earth with massive beams spanning rooms on average far larger than those in the contemporary NW/SW villages. Vintage Film of timbers, beams and posts Unlike their neighbors to the north who usually built rectangular living and storage spaces, the normal domestic rooms at Paquimé were L-shaped with a large living area matched to a smaller alcove for sleeping and storage. Other rooms at Paquimé often were eccentrically shaped with many walls; one room had 17 walls. This “architecture of power” with its large room size, massive construction, and multiple-story room block was an obvious visual signature of a thriving community of great importance as evident to ancient visitors as today’s tourist. Pans of still photos of T-shaped / Key hole doorways Much of the architecture of Paquime likely served ritual or religious purposed. One such feature common at Paquime is the T-shaped doorway. Minnis clip 6 “We really don’t know what T-shaped doorways meant to the prehistoric peoples, and nor is Casas Grandes or Paquime the only place where there were T-shaped doorways. They’ve been found at Chaco Canyon and they’ve been found at Mesa Verde.” There are two general explanations for the T-shaped doorway. One is that they are functional. For example the shape of the door could aide in navigating the opening if one was carrying a burden basket. Another is that the shape had some sort of a deeper religious or philosophical meaning to the people. Minnis clip 7 “…and that’s probably the case. We can see that by the altar stones. Those really spectacular, incredibly wellmade ground stones that were found at Paquime, one of which was found in a special tomb inside one of the platform mounds.” The bottom of the altar stone recovered from the platform mound was worn. There was some kind of behavior or ritual that smoothed and wore down the stone. We do not know what the T-shape meant but it clearly was something important to the people of Paquime, just like it likely meant something to the earlier peoples at Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde. Pan of T-shaped altar stones Vintage film of Altar Stones b. Social Structure and Ritual Paquimé was more than a domestic community; it was an important cultural center with the greatest concentration of diverse ritual architecture in the region. These attest to its primary role in the social and religious glue that held the society together. Pan over still shot of ballcourts Two I-shaped ball courts at Paquimé, much like ball courts to the south in Mesoamerica, were the largest in the Paquimé world. Di Peso also excavated what he suggested was a small ball court in a plaza. Still and Vintage Film shots of mounds Up to 15 platform mounds are at Paquimé. Most are less than 3 meter tall and geometric shaped; two are shaped like animals, a feather serpent and a decapitated bird. While common at Paquimé, we know of only one platform outside of Paquimé in the region. Vintage film of hornos (ovens), pan stills of hornos Five enormous earth ovens, one which could have cooked up to 3000 kilos of food such as the century plant (agave), likely were used to prepare feasts to feed the large crowds drawn to events and rituals centered on the ball courts and platform mounds. Stills of agave and sotol plants, cultivation and roasting Other ritually important spaces include rooms and interior shrines. Who were these leaders and how did they lead? Di Peso suggested that the rulers were long distance traders from Mesoamerica, much like the Aztec pochteca, who established Paquimé as a central trading center. There is much disagreement about how important leadership was and how much power they wielded. Were they strong rulers who had a hegemony over the community? Or was leadership more ephemeral and limited? Minnis Clip 8 “One of the bits of information that helps perhaps get clues about this is fact that there are no palaces. There are no precincts, no particular room blocks at Paquime that are so much fancier than the others, suggesting that’s where the elites lived. It may be that the elites were at Paquime and didn’t have special palaces or special houses. They weren’t as powerful as great rulers of Europe or Asia or the Middle East that had great ziggurats and great palaces at Babylon, et cetera. There’s nothing like that at Paquime. That tends to suggest that leadership was not quite as outstanding, as quite as strong, as quite as powerful, and all-encompassing as we tend to think of when we think of chiefs or leaders.” Pan on several trader illustrations from the Casas Grandes Volumes Current views tend to argue that the leaders were local inhabitants, but disagree how they ruled. Some scholars emphasize how leaders used special ritual/religious knowledge. Other archaeologists stress economic control. Whatever the source of their power or influence, there are unusual burials best interpreted as the final resting places of very special people. Still of Mound of the Offering One is a group of three individuals in a tomb embedded in the small Mound of the Offering near the central plaza. Another burial pit in a room block had elaborate artifacts. Stills of daily life illustrations from the Casas Grandes Volumes So Paquimé was a community with a large number of people going about their daily lives, much as with people in surrounding communities, and it was also an impressive center of one of the most important centers in the SW/NW, not unlike Chaco Canyon in northwest New Mexico and the Hohokam centers on southern and central Arizona. c. Water System and Agriculture Vintage film clip of excavations of canals Water was especially important to the people of Paquimé, not surprising for farmers in a dry environment. Paquimé is located along a portion the Casas Grandes River with abundant fields and access to reliable water that undoubtedly favored the farmers of Paquimé who could more easily produce surplus crops. Still images of crops + video from Tucson Botanical Gardens prehistoric garden Study of plant remains from sites along the Rio Casas Grandes river within two kilometers of Paquimé indicates that maize was the primary crop. Also grown were squash, gourds, beans, cotton, and chile. Contemporary Video shot of the Casas Grandes River and nearby current cultivated fields Contemporary video clips and/or stills of the spring About five kilometers to the north of Paquimé, a spring, Ojo Varaleño, seeped massive and dependable quantities of water as it does today. Stills of canals and reservoir from JCGE The ancient people of Paquimé built a canal that brought the water to the center of the community where it spilled into a reservoir and then flowed through small canals that snaked through the room blocks. The canal was so well engineered that is still supplies water to the modern town of Casas Grandes. The abundance of water from the river and spring and its visual display in the centrally located reservoir no doubt impressed visitors as well as providing a dependable water source. Stills of House of the Well and Casas Grandes Volumes illustration of the well In one room block there is a narrow staircase that winds its way down to the water table. This structure was dubbed “House of the Well”. Early interpretations of this site described it as a walk-in well where people could collect water for utilitarian purposes. Stills of excavated House of the Well Minnin clip 9 “That doesn’t make a lot of sense to most people nowadays. There’s is plenty of opportunity to get water. You have the reservoir that brought water to the community, the river isn’t that far away. Is a community of several thousand people going to use this highly restricted, little pool at the bottom of a dark tunnel? It was probably a water shrine of kind. That’s what most people think and that’s probably the case. And when they found it they found a lot special, exotic and rare items strewn over the stairs at the top, which were probably offerings when the water shrine was closed.” d. Economy and Trade Of course, a large community produced many articles used in their daily tasks. Their remains, such as grinding stones, utilitarian pottery, and stone tools were found in the hundreds and thousands by the JCGE. Many of these were trade goods that were imported into the Paquime community. Stills of metates, ceramics, axe heads Most attention, understandably, is drawn to the special and exotic artifacts. One and half tons of shell artifacts were found, mostly in a few rooms. Stills of Shells It is unclear if shell objects were important for economic or ideological reasons. The scale of shell at Paquimé certainly bespeaks of an economically important commodity. The fact that a majority of the objects found in burials were shell ornaments likewise indicates an economic function or role. Vintage film of shell screening, jewelry reconstruction, etc. Hundreds of copper artifacts of various types were also common. Stills of copper recovered The shell and copper came from the west coast of Mexico. Special goods of more local origin, such as minerals, were also recovered by Di Peso and his crew. For example, most unworked mineral fragments were found in special store rooms that also housed the majority of shell artifacts. Stills of raw minerals Interpretation of the role of these very special artifacts has changed through time. Di Peso interpreted them as evidence that Paquimé was a major trade center linking the SW/NW with Mesoamerica. More recent interpretation emphasize these goods as parts of an elaborate and every changing ritual, political, and social landscape where special goods were used as symbols by leaders and other goods were offerings. Ceramics Stills of Ramos Polychrome vessels from Amerind collections and in galleries Ceramics are valuable in that they can tell us much about the peoples that made them. In many communities and cultures we find signature ceramics that tell us that these people knew each other and were a part of a cultural tradition. No material object associated with Paquimé attracts as much attention from both the public and scholars as the delightful polychrome pottery vessels. The exquisitely made Ramos Polychrome vessels were the signature pottery type of the Casas Grandes complex. Stills and vintage film of ceramics recovered at Paquime These vessels are often adorned with various images, designs, and symbolism that relates to the beliefs of the people. While little direct evidence of pottery production exists from Paquimé, what there is of it does not suggest a level of production technology above that of other prehispanic communities in the region. Nothing at Paquimé suggests a level of production above the household specialist, a pattern that is common throughout the Southwest. However, if contemporary ceramists in the nearby village of Mata Ortiz are any indication of skill level Stills of Mata Ortiz and potters in action – the Mata Ortiz pottery and finely crafted Ramos Polychromes show a similar level of production ability – then certainly some of the ancient ceramists were able to produce pottery of the same quality as modern day full-time specialists. Spencer MacCallum clip 1 Importance of Paquime and associated sites to the emergence of the ceramic revolution in Mata Ortiz. Diego Valles clip 1 What Paquime means to potters in Mata Ortiz. Many techniques used by contemporary potters likely match that of the prehistoric artists at Paquime. Macaws and Turkeys Minnis clip 10 “If there is one thing that really excites people when they learn about Paquime it’s the scarlet macaws. These multicolored birds from far down in central Mexico. They weren’t naturally found any closer than 700 miles away. And yet people at Paquime were able to raise these birds, and remains of hundreds of them as well as their cages were found at Paquime. Contrast that to other areas that had macaws in the Southwest. Mimbres; a few dozen, Chaco Canyon; a few dozen; Wupatki; a few dozen, yet there were hundreds of them at Paquime. It was a great source of wealth and power.” Macaw production at Paquimé was so unique and extraordinary to Di Peso that he referred to unit 12 as the House of the Macaws. Di Peso interpreted the various evidence for macaw husbandry at Paquimé as indicative of full-time, specialize aviculturists. Specialists may have attended to daily chores of feeding and watering the birds and tending to their nesting boxes. An astonishing 322 scarlet macaws were recovered at Paquimé, considerably more than have been found at other sites throughout the northwest Mexico / American Southwest region. An additionalal 81 military macaws and 100 macaws of undesignated species were also discovered at Paquimé. There is little doubt that Paquimé represents a prehistoric concentration of these valuable birds. 56 pens were discovered with macaw remains and feces. However – and luckily for archaeologists and unluckily for macaw breeders - macaws are notoriously destructive of cages and thus the Paquiméans built cages with stone ring doorways and stone plugs that the birds could not destroy with their powerful beaks. Thus it seems that the ancient Paquiméans had not only imported these tropical birds from further west and south in Mexico, but had established and maintained a breeding population. Di Peso saw a fairly large-scale turkey domestication and production system at Paquimé. He concluded that hundreds of turkeys were raised, “herded” during the day and allowed to roost in pens at night. He further argued that the Paquiméans kept three different breeds, one of which was a hybrid of their own. Since limited cut marks were found on the few turkey remains found it trash deposits, he concluded that the turkeys were raised for feathers and as sacrificial animals, not for food. 220 of the turkeys found were intentionally buried, articulated, and headless suggesting that they were used as sacrifices. Di Peso’s reconstruction of production at Paquimé as involving a series of craft guilds was clearly inspired by the pochteca explanatory framework he developed for the rise of the community. However, a more critical review of the evidence suggests that in many ways commodity production at the site was not much different than that seen in other areas of the American southwest and northern Mexico. In terms of the locally produced objects (ceramics, metates, turkeys, and agave) household production probably accounts for much of the materials recovered. There is limited evidence for a restricted distribution of these objects. Certainly most Paquiméan were able to acquire polychrome ceramics, metates, and turkeys for sacrifice and probably participated in large feasting events represented by the roasting pits. In terms of the non-local commodities, it appears that Paquimé was principally an end consumer of items like shell and turquoise and copper objects. Turquoise was probably acquired in finished form from areas to the north and east while shell and copper almost assuredly came from the west Mexican coast. Macaws were also probably originally acquired from west Mexico, though subsequently the Paquiméans may have managed a breeding population to supply their needs. Each of these non-local objects were probably ritually or ceremonially important. Cerro Moctezuma There are numerous nearby sites that are part of the Casas Grandes complex. One is a hilltop site called Cerro Moctezuma. Di Peso argued that this was a fire communications system, and it may well have been. Recent studies of the site support the idea that this was also likely a shrine and certain rituals would have been performed atop the hill. Associated with Cerro Moctezuma is a small site called El Pueblito. This was likely not a standard domestic community, but perhaps a staging area for rituals at Cerro Moctezuma. V. Current Research and Future Endeavors The Joint Casas Grandes Expedition ended in 1961. They packed up and moved on. Eduardo Contreras went back to Mexico City. Charles Di Peso returned to the Amerind with his colleagues and spent over a decade putting together the wonderful 8 volumes of data from the excavations. One would have thought that the work done by Di Peso and Contreras would have whet the appetite of archaeologists and research in the region would explode. Unfortunately that did not happen. Mexican archaeologists continued to be mostly interested in Central and Southern Mexico. North American archaeologists rarely ventured south of the border. For 25 years following the Joint Casas Grandes expedition very little work was done in the region. In the 1980s researchers from Canada, the United States, and Mexico began a series of projects that has been a new renaissance of archaeology in Northwest Mexico. These projects have been an extension of the Joint Casas Grandes Expedition, expanding ideas and sometimes correcting when current researchers come up with new interpretations. We can only hope that this new work in sustained and expanded as time goes by and that there isn’t another period of neglect in the region. The big unanswered questions at Paquime are: How and why did Paquime begin? And How and why did it end? VI. Concluding Thoughts What we know about Paquimé is almost entirely due to JCGE. It also excavated sites before and after the Medio Period, and it conducted some regional reconnaissance in northwestern Chihuahua. Today, we are witnessing another renaissance in Chihuahua archaeology with numerous projects directed by scholars from three countries. These projects are working toward understanding the Medio Period but others are also studying earlier and later time periods to gain as better appreciation of the prehistory of this long neglected part of the SW/NW. In addition, INAH has built a world-class museum at the site and has increased investment in research. In light of Paquimé’s cultural value, UNESCO designated it a World Heritage Site in 1998. This research renaissance and long overdue recognition is built on the rock-solid legacy of the JCGE, a contribution this book is meant to celebrate. Have David Di Peso read several excerpts from the daily log Voiceover from Di Peso’s daily log about the song some of the crew put together Still shots of band playing in the ruins Audio of Jesus Garcia’s rendition of the Corrido de Paquime.