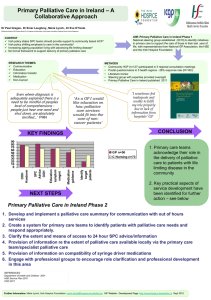

Briefing document fr... - Irish Hospice Foundation

advertisement