Braddock

advertisement

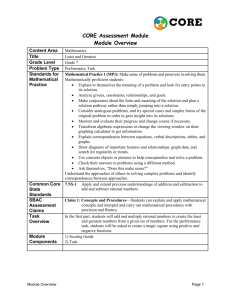

Contagious Animism in the artwork of Felix Gonzales Torres and Dane Mitchell Christopher Braddock This article discusses two installation artists—Felix Gonzales Torres and Dane Mitchell—whose work explores a dispersion, or residue, of materials in ways that engage audiences in forms of unwitting participation. A unique aspect of the article is that these forms of participatory installation practice are explored through theories of so-called ‘primitive’ or ‘savage’ magic ritual. To be more specific, magical concepts of ‘contagion’, ‘animism’ and ‘ritual participation’ are employed to open up a range of hotly debated questions about reciprocity between people and things, and, in turn, where ‘liveness’ lives. The article is based on a provocation—Jacques Derrida’s notion of the ‘trace structure’ is profoundly ‘savage’ in its assertion that the sign has a real connection with its world. That word ‘savage’ is used by late-nineteenth-century British anthropologists Edward Burnett Tylor (1832-1917) and James George Frazer (18541941). They were baffled by the continuation of so-called ‘savage’ beliefs and practices in their own contemporary societies. They managed, in fact, to disavow aspects of their own Christian heritage that involved some of the very animistic operations they saw as ‘savage’ in their concurrent ethnographic work. Their disbelief in the force of magical ritual was partly due to their racialized and evolutionarydriven concept of ‘primitiveness’. In their minds, Culture, in opposition to the darkness of savage Nature, gradually became more and more civilized until its culmination in the white male Victorian intellect. What those anthropologists observed in ‘savage’ magical practices was a breakdown in oppositional structures of life and death, organic and inorganic, subject and object, whiteness and blackness, linked to the possibility of a ‘force’ that precedes those terms related and contagiously infiltrates all materiality beyond reason. This, it turns out, is a staple of Derridean deconstruction and the notion of différance or the ‘trace structure’. Discussing Felix Gonzales Torres’s ‘Untitled’ (Lover Boys) series (from 1991), and New Zealand artist Dane Mitchell’s 2011 Radiant Matter series, this paper argues that the label ‘savage’ is always already in excess of those ethnographic and historical constraints. Put another way, there are no savages, there never were. Or, put another way again, we 1 are all savages.1 Through the consumption of candies (Torres), or the activation of vaporous environments (Mitchell), these artworks provoke ideas of contagious and vital fields of affect that provoke unwitting forms of participation that operate beyond the senses. What follows is a discussion in three parts. I begin with an outline of James George Frazer’s definition of ‘sympathetic magic’ while mindful of Felix Gonzales Torres’s artwork. I then touch on Marcel Mauss’s (1872-1950) notion of ‘effluvia’ which ‘travel about’ (1975: 72) from his A General Theory of Magic written between 1902 and 1903.2 I interpret ‘effluvia’ as a vaporous and contagious field of affect in relation to Derrida’s notion of the ‘trace structure’. Finally, I conclude with a critique of Dane Mitchell’s artwork alongside mention of Mauss’s contemporary Lucien Lévy-Bruhl (1875-1939) and his concept of ‘mystical participation’. Lévy-Bruhl describes a realm where ‘substance’ is an immeasurable essence that amounts to participation because it is participated in. Part 1: James George Frazer’s sympathetic magic In his now infamous publication The Golden Bough (1890–1915), Frazer devises two laws, one of similarity and the other of contact, that function under the general name of ‘sympathetic magic’. The first of these laws involving imitation or mimesis is underscored by the notion that ‘like produces like, or that an effect resembles its cause’ while the second, involving contact, assumes that ‘things which have once been in contact with each other continue to act upon each other at a distance after the physical contact has been severed’ (Frazer 1924: 11). Frazer further clarifies his terminology to describe this law of similarity as homoeopathic while the law of contact he defines as contagious magic.3 In this context, he defines the most common See Christopher Bracken as he writes: ‘There is no such thing as a savage society, nor has there ever been. Savage philosophers are the outgrowths of discourse, and they dare us to think more by daring to enrich signs with a principle of change’ (2007: 21). 2 As Michael Taussig notes that, while this work is attributed to Marcel Mauss, the original Année sociologique essay is credited to joint authorship of Henri Hubert and Mauss (1993: 258n14). 3 James George Frazer’s use of the term ‘homeopathic’ is a manifestation of the (metonymic) idea in homeopathy that a diluted element (a part of a whole) carries the healing force of the whole. 1 2 forms of contagious magic as the magical sympathy which is supposed to exist between a man and any severed portion of his person, as his hair or nails; so that whoever gets possession of the human hair or nails may work his will, at any distance, upon the person from whom they were cut. (38) His terms of reference are very generalized and he extends this notion to items of clothing and impressions left by a body, including the possibility of injuring footprints in order to injure the feet that made them. The ‘natives of South-eastern Australia’, Frazer says, ‘think they can lame a man by placing sharp pieces of quartz, glass, bone, or charcoal in his footprints’ (44). And Frazer concludes this section of The Golden Bough dedicated to ‘Sympathetic Magic’ by referring to ‘a maxim with the Pythagoreans that in rising from bed you should smooth away the impression left by your body on the bed-clothes’ (45). Felix Gonzalez-Torres, ‘Untitled’ (Lover Boys), 1991, candies individually wrapped in clear cellophane, endless supply. Overall dimensions vary with installation. Ideal weight: 355 lb. Photo: Axel Schneider, Frankfurt-am-Main © The Felix GonzalezTorres Foundation. Installation view of Specific Objects without Specific Form at the Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, Germany, 2011. This idea that things might ‘act on each other at a distance through a secret sympathy’ is key, for example, to a series of artworks by Felix Gonzalez-Torres titled ‘Untitled’ 3 (Lover Boys). The first of these installations, installed in 1991 at Xavier Hufkens Gallery, Brussels, employed a 355 lb pile of candies equal to the combined body weights of Gonzalez-Torres and his partner Ross who died from AIDS in 1991.4 This pile of candies on the floor of the gallery conjures up the possibility that this ‘like’ weight produces or performs them both and that the effect of this work will resemble its cause—will effect an ongoing unity of artist and lover embodied in the bodies of the participating audiences who are free to consume the candies one by one as they pass by the work. Artist and lover, as ‘donors’ of this ritualized (votive) offering, therefore implicate the bodies of the audience in a profound form of contact (understood as contagious ‘contiguity’) through digestion, implicating the bodily nourishment of those viewer participants. By inversion, these are the objects of the viewers’ performance where those participating perform the work. As those participants leave the gallery they disperse, literally around the globe, continuing the action of their participation at a distance, long after their physical contact has been severed. These are the powerfully so-called ‘savage’ operations of sympathetic magic at work in everyday consumption. Gonzalez-Torres’s candies are animated (in the order of the spell) by the utterance of the title, and related instructions stipulating the deployment of the work at each exhibition venue. Those participants do more than just suck on a candy. They consume (and thereby embody) the gay relationship. They become themselves animated by the magical ‘effluvia’ of the artwork, to coin Marcel Mauss’s term.5 In this sense, while Gonzalez-Torres’s formal aesthetic (and content) would seem not to derive from a history of magic, its operational force is deeply ‘magical’. The nature of the candy pieces is that they can also be installed at alternate weights. For example, the work ‘Untitled’ (Revenge) has an ideal weight of 325 lbs (first installed in Madrid in 1991). Also during Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s lifetime, in 1994, he installed the work at 1000 lbs at the Renaissance Society in Chicago. For further context, when asked by Bob Nickas when interviewed for Flash Art, Nov/Dec 1991, p. 89, ‘Can you talk about how the candy pieces relate to memory and the body?’, Gonzalez-Torres replies, ‘The pieces called Lover Boys are piles of candy based on body weights. I use my own weight or mine and Ross’s together. If I do a portrait of someone, I use their weight.’ Thanks to Allison Hemler, Director of Archives and Communications, The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation, for these details. 5 This concept of ‘participation’ as an uncontrollable and contagious ‘trace structure’ is also exemplified by Jacques Derrida’s notion of the impossibility of the gift. From this perspective, I would not know I am being given the relationship and they would not know they have given it to me. Thus the ‘value’, or ‘force’, of the artwork precedes the participants. 4 4 This thinking is partly made possible by the work of anthropologists in the 1960s such as Sri Lankan-born Stanley J. Tambiah (b. 1929) who argued that magic acts should be interpreted as performative acts rather than judged on the basis of scientific verification (1973: 199). In other words, to ask if magic works in terms of cause and effect is to have asked the wrong question. Instead he interprets magic ritual as engaging with objectives of ‘persuasion’, ‘conceptualisation’ and ‘expansion of meaning’ (219). Thus he proposes as a new theory of magical language which helps retrieve a philosophy of language from its racist heritage and therefore from preconceptions associated with ‘black’ magic. Accordingly, Tambiah develops an understanding of so-called primitive thinking in ritual as underpinned by a theory of performatives in an understanding of the agency of magic. In other words, it becomes a question of what the ‘performativity’, which is the practice of magic, does. This, therefore, allows an application of the theories of magic to coincide with theories that privilege the artwork as a process. In this sense magic is a ‘harnessing of forces’, an expression used by Simon O’Sullivan (employing the ideas of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari) in suggesting the artwork is a ‘creative deterritorialisation into the realm of affects’. With this in mind, O’Sullivan continues (without subsequent mention of magic): ‘Art might be understood as the name for a function, a magical and aesthetic function of transformation’ (2006: 52). The immense importance of Tambiah’s contribution (and others dealing with the linguistic properties of ritual6) lies in the fact that he re-examines a ‘discredited’ nonmodern worldview (that conceives of things as animated) through a concept of performative agency. He thus gives us back that discredited history in ways that enable us to re-consider what concepts like ‘magic’, ‘animism’ and ‘spiritual essence’ might signify. This, in turn, potentially enables us to reconsider our worldview in the light of those so-called ‘savage’ histories. This creates a remarkable challenge to reStanley J. Tambiah was certainly not alone in his thinking of the performative nature of ritual and the application of, for example, the performative theories of language by J. L. Austin. See, for example, Ruth Finnegan, ‘How to Do Things with Words: Performative Utterances Among the Limba of Sierra Leone,’ Man, n.s. 4, no. 4, 1969, pp. 537–52, especially pp. 548–550. As Catherine Bell notes: ‘Finnegan also pointed out that the notion of performative utterance solves the difficulties posed by a polarization of utilitarian-functionalist versus expressive-symbolic styles of speech and action, which was, of course, the type of distinction that kept differentiating magic, science, and religion, as well as drawing distinctions between primitive versus modern’ (1997: 69n28). 6 5 thinking the boundaries between subjects and objects, nature and culture, the psyche and the material world. Frazer, of course, would be hostile to Gonzalez-Torres’s so-called ‘savage’ thinking. He and his Victorian contemporaries equated the possibility of contagious animism with savage race relations. And in this respect, scholars such as Christopher Bracken argue, the philosophy of language is partly based on differences between races and has enforced a separation between signs and things. He writes: ‘The point is that a difference between races has been projected onto an enduring scholarly debate about the relation between signs and things’ (2007: 6). Part 2: Marcel Mauss’s effluvia The historical ethnography on magic grapples with the concept of ‘animism’ as a belief that things in nature might possess consciousness, and a belief that people have spirits that can exist separately from their bodies, contaminating other objects and people. This is part of the overall concept of ‘contagion’ which sustains a view that ‘liveness’ does not reside in bodies or in things. It resides in what Mauss calls ‘effluvia’ which ‘travel about’ (1975: 72). In discussing the possibility that we have already encountered with Frazer—that things act on each other at a distance—Mauss struggles with such a resistance to conventional notions of time and space. Hence he says that action at a distance involves ‘the idea of effluvia which leave the body’.7 In characterizing ‘magical images which travel about’, Mauss cites an example from the Malleus maleficarum8 of ‘a witch who dips her broom in a pond to bring on rain and then flies away into the air to search for it’ (72-3). Read here, Torres's audiences who take a candy (thus bringing on participation) and then fly away in search of it and so on. Significantly, Mauss develops this idea of ‘effluvia’ as ‘mana’. This is a force and/or As a continuation of this discussion about ‘action-at-a-distance,’ see Chapter 2 of my forthcoming book Performing Contagious Bodies where I propose the ‘sym’ of ‘sympathy’ and the ‘tele’ of ‘telepathy’ as two modalities of affect. 8 The Malleus Maleficarum (Latin for ‘Hammer of the Witches’, or ‘Der Hexenhammer’) is a treatise on witches written in 1486 by Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger, Inquisitors of the Catholic Church, and was first published in Germany in 1487. 7 6 power or ‘magic potence’ which Mauss understands as ‘the presence of a kind of magical potential’ (107, 113, 121).9 To get to this conclusion, Mauss has asserted an ‘idea’ of magic as ‘a field where ritual occurs … a place where spirits come alive and where magical effluvia are wafted’ (118). This ‘idea’ (as distinct from the ‘outer form’ of magic) becomes crucial for Mauss, and it is this ‘idea which animates all the forms assumed by magic’ (118). This ‘idea’ develops into an understanding of magic as a ‘social phenomenon’, as a ‘functioning of collective life’ and ‘collective thinking’ (119, 121). It is only ‘a non-intellectualist psychology of man as a community’, says Mauss, that will tolerate this ‘idea’ of magic (108). From this perspective, Mauss’s contemporary Lucien Lévy-Bruhl (1875-1939) can say in his Notebooks on Primitive Mentality written between 1938 and 1939 that ‘participation’ exists as a felt experience of a community of essence which has an equivalence to the act of participating. He writes: ‘participation between the individual and his appurtenances (hair, nails, excretions, clothing, footprints, shadows, etc.) …. equals a community of essence [as an] identity felt between what participates and what is “participated in” ’ (1975: 108). Thus Lévy-Bruhl’s notion of ‘mystical participation’ describes a field of participants already affected (or contaminated) and not a verifiable or rational play between elements, living or dead or inorganic. It is there because it is participated in. As Rodney Needham notes, the overwhelming breakthrough that Lévy-Bruhl offers at this time was a realization that ‘the strangeness of primitive mentality were not mere errors, as detected by a finally superior rationality of which we were the fortunate possessors, but that other civilizations presented us with alternative categories and modes of thought’ (1972: 183). Lévy-Bruhl’s concept of of ‘mystical participation’ (discussed further in Part 3 of this article) describes a realm where ‘substance’ is an infinite essence that equals participation because it is participated in. From this key idea I argue for an ontology of participation that emphasizes a ‘value’ or meaning that precedes the terms related of subject/object, organic/inorganic. Moreover, things (and their substances) cannot be determined by a ‘series of antecedents which result in some event’ Lévy-Bruhl Mauss is referencing the contemporaneous ethnographer of the North American Huron (Iroquois), J. N. B. Hewitt, as he develops this idea of ‘effluvia’ as ‘mana’. 9 7 writes (1975: 133). Instead, they telepathically operate across space and time because they precede the terms related (animate and inanimate). Thus this mode of thought suggests an existent or a there in a field of affect that is already infiltrated, already contaminated, and exceeding participants. But here the term ‘participants’ is expanded to acknowledge all the secondary terms in an arbitrary dichotomy of animate/inanimate, subject/object, presence/absence and so forth. This, as said at the beginning of this article, is a significant aspect of Derridean deconstruction and the notion of différance or the ‘trace structure’. In his address to the French Society of Philosophy on the 27th of January 1968 titled Différance, Derrida calls this inseparability and unlocatability of these binary terms a double gesture that shares the characteristics of temporization and spacing. As an abbreviated overview, Derrida explains that the verb ‘différer’ carries two meanings: one associated with ‘a detour, a delay, a relay, a reserve’ which acts as a ‘temporization’ in time that ‘suspends the accomplishment or fulfillment of “desire” or “will” ’ (8). The second meaning is associated with a space between polemical terms such as speech/writing, subject/object, organic/inorganic that is not identical to another as ‘an interval, a distance, spacing’ that is produced in repetition (8). Accordingly, the word différance (with an ‘a’) compensates for the word ‘différence’ in that it simultaneously refers to this ‘temporization’ and the polemical while also denoting an undecided sense of movement as neither active or passive (8-9). This suggests that there can be no sense of an ‘action of a subject on an object’ (9). This will mean a radical deconstruction of a notion of presence (or ‘liveness’) and how it might be understood to operate, even telepathically, in relation to time and space. I argue that the operations of sympathetic magic incite these qualities of the ‘trace structure’ in différance. The audacity of magic ritual is that it presumes that the sign is the thing. The footprint, the saliva, the breath, is the person. The operations of Derrida’s trace structure as a temporization in time and spacing as action at a distance, like magic, questions a classical understanding of the ‘sign’ as meaning a ‘representation’ of presence. When Frazer says of the operations of sympathy and contact (to repeat an earlier reference) that ‘like produces like’ or that ‘things which have once been in contact with each other continue to act upon each other at a 8 distance after the physical contact has been severed’ (1924: 11), he grapples with an idea that he cannot tolerate: that the ‘trace’ of these magical operations might constitute a questioning of presence (the implications of which are profound in questioning the value of a unified, cognitive subject). The ‘trace structure’ helps us understand that Frazer’s ‘Law of Contagion’ (in its combination of similitude and contact) reveals an already contaminated field; an ‘effluvia’ as a contaminated relationality that precedes and exceeds the terms related (subject/object, presence/absence). As I will continue to argue, this already contaminated field is important to an understanding of Torres’s and Mitchell’s artworks. Part 3: Dane Mitchell’s Radiant Matter For Various Solid States (2010/2011) as part of Radiant Matter I at the GovettBrewster Art Gallery, Mitchell’s instructions to the staff are specific but openended—pour one cast per day but more if humid conditions create enough fluid. Perform this task before the gallery opens but a little after is fine (or during the day if necessary), and try to pour shapes that are ambiguous, that is, not too figurative (thus avoiding Mickey Mouse ears and so forth). Following these instructions, each morning gallery staff retrieve water, accumulated overnight in a dehumidifier, to mix plaster from the 20 kilo bags stacked adjacent in the same exhibition space. After removing the previous (now set) plaster pour and propping it against the walls of the gallery— along with all the other plaster casts from previous days—the fresh plaster mix is poured out onto a roll of bubble-wrap, itself a membrane of stored air pockets. Mitchell describes this process as a ‘transformation of matter from one state to another’ in the simplest possible terms. Accordingly, the techniques employed are domestic, or studio based, while the atmosphere captured is, Mitchell comments, ‘infused with our own liquids, our own exhalations’10 Conversation with the author, 5 July 2012. I thank Dane Mitchell for his generosity in the preparations for this article. 10 9 10 Dane Mitchell, Various Solid States, 2010/2011, de-humidifier, water, plaster, aluminum, bubble wrap, sieve. 1000mm x 5000m x 5000m. From the exhibition Radiant Matter I at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, New Zealand, 5 March 2011 — 29 May 2011. Photo: Bryan James. Courtesy the artist, supported by the artist residency programme, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand. As another activation of vaporous environments, Epitaph (2011)—as part of Radiant Matter II, at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery—employs an empty late-Victorian vitrine from the holdings of the Dunedin Public Art Gallery. Each morning gallery staff are instructed to open the rear glass door of the cabinet and spray a quantity of scent onto its mirrored base. Through a 20 CM hole cut in the frontal glass face of the vitrine, the viewer is able to lean forward, slightly into the hole, and sniff the scent.11 Mitchell explains that the fragrance (made in collaboration with the perfumer Michel Roudnitska) includes a synthesized reproduction of musk produced by the civet cat: an intensely bodily odor. Using such an aroma, Mitchell is attempting to activate smell as a medium, or ‘effluvia’, that resists definition and one that reaches back into our animalistic and sexualized primordial responses.12 As Aaron Kreisler notes: ‘Working with the perfumer Michel Roudnitska, Mitchell produces a scent whose base notes allude to a bodily (ghostly) presence, with a lingering hint of dust. The potency of this synthesised perfume is both amplified and clarified by its placement in a seemingly empty late Victorian vitrine’ (2011: 38). 12 Conversation with the author, 5 July 2012. 11 11 12 Dane Mitchell, Epitaph, 2011, perfume, mirror, cabinet. 1030mm x 1830mm x 860mm (cabinet). From the exhibition Radiant Matter II at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, Dunedin, New Zealand, 28 May 2011 — 28 August 2011. Photo: Bill Nichol. Courtesy the artist, supported by the Dunedin Public Art Gallery visiting artist 13 programme. This assertion is further emphasized in Mitchell’s more overt references to magic ritual. For example, Gateway to the Etheric Realm (2011) as part of Radiant Matter II displays the remnants of magical spells and cantations. Mitchell hired the services of a local witch to enter the exhibition space for six private rituals, leaving behind the debris of crystallized dragons blood, herbs, owl feathers, infused blessed water, incense, charcoal and salt. Adjacent to this artwork, Etheric Realm Spell Materials (2011) stacks glass vials with these material residues, in turn, encasing these vials in a glazed picture frame. These direct references to magical practices alert us to a realm that cannot be justified by scientific intellectualization. Dane Mitchell, Gateway to the Etheric Realm, 2011, powder-coated steel, spell, spell materials. 6000mm x 6000mm x 3250mm (approximately). From the exhibition Radiant Matter II at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, Dunedin, New Zealand, 28 May 2011 — 28 August 2011. Photo: Bill Nichol. Courtesy the artist, supported by the Dunedin Public Art Gallery visiting artist programme. 14 Dane Mitchell, Etheric Realm Spell Materials, 2011, frame, glass, rubber, salt, dragons blood, smoke, rosemary, water, dirt, feathers. 1450mm x 1275mm x 100mm. From the exhibition Radiant Matter II at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, Dunedin, New Zealand, 28 May 2011 — 28 August 2011. Photo: Bill Nichol. Courtesy the artist, supported by the Dunedin Public Art Gallery visiting artist programme. The artworks of Torres and Mitchell complicate distinctions between art as commodity or aesthetic form. In turn, they amplify our experiences of participation as uncontrollable encounter. Our saliva, our exhalations, or those vaporous scents, infiltrate all matter. Or put another way, those plaster shapes and that perfume are inseparable from us and our breathing vapour. Likewise, magical rituals—in their ‘purported’ ability to confound boundaries between a natural world of objects, material substances and human bodies—present, in the words of Frazer, ‘a spurious system of natural law as well as a fallacious guide of conduct’. It is ‘false science as well as an abortive art’, continues Frazer (1924: 11). In this sense, the possibility of ritual contagious animism threatens the foundations of Platonic mimesis. Plato banishes the artist from the city, not so much because of a threat to truth, but because of a threat to order. ‘Through his doublings and multiplications’, Christopher Prendergast writes, ‘the mimetic artist introduces “improprieties” (a “poison”) into a social system ordered according to the rule that everything and everyone be in its/his/her proper place’ (1986: 10). Let’s not forget that Plato’s Socrates says that imitation is about ‘looks’ and not the ‘truth’ and ‘it is due to this that it produces 15 everything—because it lays hold of a certain small part of each thing, and that part is itself only a phantom’ (BookX/598b). As such, Plato’s Socrates speaks of the artist as wizard and imitator. Thus, Plato’s Socrates continues, ‘he has encountered some wizard and imitator and been deceived’ (BookX/598d). In this way, Plato provocatively positions the artist as the source of magical utterance.13 Moreover, magic’s combination of body substances (breath, saliva, aroma, spittle, nails, hair, etc.) with other materials (plant residue, ashes, etc.), like Torres’s candies dissolved in the mouths of participants and Mitchell’s transformation of our vaporous exhalations, provokes an idea of consubstantiation between persons and things; it conjures forth the already contaminated field of the animate and inanimate, living or dead. In this respect, Mitchell deploys smell or aroma as a performative encounter. When Mitchell says of his project Radiant Matter that he deploys ‘perfume as a concentrated form of loss’ he is engaging with a ‘trace structure’ where, Derrida says, ‘erasure’ forms its constitution ‘from the outset as a trace’ (1982: 24). Perfume will always evaporate and in this sense it lacks clear description or defies definition. This is radical because the sign (the aroma) does not represent. Again in the words of Derrida, this operation ‘makes it disappear in its appearance’ (24). In this realm—like Mauss’s effluvia—‘substance’ is an infinite essence that exists as a felt community because it is participated in. Lucien Lévy-Bruhl’s concept of ‘mystical participation’ The remaining discussion is dedicated to the extraordinary insights of Lévy-Bruhl and his emphasis on collective representations that led him to argue that participation was not a comprehensible relation between individuals or things. For example, in discussing the participation between a corpse and its ghost, LévyBruhl asserts that: ‘It is equally true to say that the corpse is the deceased, and that it is not.’ ‘This proves’ he continues, ‘that neither expression is correct’ (1975: 1). He qualifies this statement by affirming that this notion of ‘participation’ cannot presuppose a connection or representation, it occurs simultaneously with them: See The Republic of Plato, (Allan Bloom, Trans.), New York: Basic Books (Plato 1991: 281). 13 16 participation is not established between the more or less clearly represented deceased and corpse (in which case it would be of the nature of a relationship or connection, and it should be possible to make it easily comprehensible); it does not come after these representations, it does not presuppose them: it is before them, or at least simultaneous with them. What is given in the first place is participation. (2) When Lévy-Bruhl says ‘what is given in the first place’, he questions a notion of ‘presence’ as a ‘concept’ that appears a priori before participation’s affect. Thus, he calls attention to the labels ‘presence’ and ‘absence’, or ‘subject’ and ‘object’, that problematically presuppose the presence of those concepts before their relation. If a notion of ‘participation’ is thought of as a ‘concept’, he argues, it becomes ‘necessary to involve the presence of those concepts of the things between which the participation is established’ (3). Lévy-Bruhl does not want to put the concept of the sign—that which Derrida says, ‘always has meant the representation of a presence’ (1982: 10)—in place of the thing itself. Magic, in this way, undermines the presumed secondary and provisional nature of the sign and dares to question the authority of presence, or of its simple symmetrical opposite, the inanimate and dead.14 We recall Derrida’s discussion of the ‘trace structure’ as différance where this ‘term’ is neither a word nor a concept. It is this ‘interval’ of meaning, Derrida notes, that ‘maintains our relationship with that which we necessarily misconstrue, and which exceeds the alternative of presence and absence’ (20). In this sense, Lévy-Bruhl’s notion of ‘participation’ has nowhere to begin. Magical participation therefore calls into question what Derrida refers to as ‘a rightful beginning, an absolute point of departure, a principal responsibility’ and therefore opens up a question of value as a controlling principle and system (6). This kind of ‘savage’ thinking about a concept of ‘participation’ urges Lévy-Bruhl to abandon an intellectualization of what he calls ‘mystical participation’, where, he says in a very Derridean fashion, ‘even simply expressing it in our vocabulary with our concepts, falsifies it’ (1975: 1). Moreover, in introducing an inability for western ethnographers to comprehend what he termed ‘primitive mentalities’, he puts in place a vastly significant milestone for future developments in cultural anthropology. Not only is an intellectualization of ‘mystical participation’ a problem for the ethnographic ‘framing’ of other peoples (in that it I am following Derrida’s phrasing here when he says that différance ‘puts into question the authority of presence, or of its simple symmetrical opposite, absence or lack’ (10). 14 17 presents us with alternative categories of thinking outside our own experience), it raises the potential impossibility of comprehending a field of affective participation. Hence, Lévy-Bruhl sees magical or mystical participation as ‘the affective category of the supernatural’ that is ‘not represented but felt’ (4-5, 106, 158).15 In short, participation cannot be determined through antecedents but in the course of participation (Lévy-Bruhl 1975: 133). In this context, Lévy-Bruhl makes a striking example of Melanesian languages and their names for a person’s finger (natugu or natuku) that combine, he deduces, possessive and personal pronouns that attribute the finger as ‘finger of me’ (107). This, he deduces, means that ‘this finger is me through participation (in the sense where to be is equivalent to to participate)’ (107, emphasis added). This means that participation precedes the identity of the finger. Furthermore, he makes this observation while categorizing the finger as an ‘appurtenance’—that is, an accessory or adjunct to the human body suggestive of a reassessment of the finger’s subjecthood and positing the idea of the finger as neither part subject or object. Rather, identity occurs simultaneously in participation. In these ways Lévy-Bruhl re-configures a concept of ‘animism’. Rather than a spiritual supplement that intervenes from an exterior source (as a life/matter binary), he understands ‘mystical participation’ in the operations of magical ritual as emerging from collective and incomprehensible dynamics. This relational dynamic is nonrational because it precedes an organic/inorganic divide. To say again that extraordinary claim by Lévy-Bruhl cited above: ‘What is given in the first place is participation’ (2). Conclusion See Benson Saler who borrows from Jean Cazeneuve’s analysis of Lévy-Bruhl where this ‘affective’ category becomes ‘that of the role of affectivity of thought’ (2003: 48). Saler is quoting Jean Cazeneuve, Lucien Lévi-Bruhl, Peter Riviere (trans.), New York, Harper and Row, 1963, p. 22. With respect to Lévy-Bruhl’s notion of ‘participation’, Saler argues for an ‘attempt to explore the affective as well as cognitive significance of beliefs for those who affirm them’ (55). To my mind his discussion that ‘the border between these analytical domains is unstable and fuzzy’ (55) does not fully account for LévyBruhl’s attempt to abandon categorization of ‘participation’ as incomprehensible. 15 18 The artworks of Felix Gonzales Torres and Dane Mitchell engage in fields of contagious affect that infiltrate all bodies (animate or inanimate) in forms of ritual participation. This means, not just we ‘subjects’, but us ‘objects’ too. Our habitually polemical categorizations of people and things are made problematic in a radical questioning of where ‘liveness’ lives. This highlights modes of unwitting participation in which ‘value’ or meaning precedes the terms related of subject/object, organic/inorganic. From this perspective, ‘liveness’ does not reside in bodies or in things. It resides in what Mauss calls ‘effluvia’ which ‘travel about’ (1975: 72). Here, the sign—like Mitchell’s effusive aromas—appears beyond reasonable representation as a collective dynamic inseparable from bodily encounter. This way of thinking about a dispersion, or residue, of materials in performative installation art (and the objects of performance as such) allows for intense alternations of time (temporization as deferment) and space (interval and distancing as differentiation). We recall here Tambiah’s main objective in all his approaches to anthropology, which is to overturn an ethnographic view of (black) magic as a ‘primitive’ and failed science and to lend it instead the agency of performativity. Here, the force of the trace refers us beyond any intellectualization of participation and beyond language to the point that we ask what other language this is (Derrida 1982: 25). References Bell, Catherine (1997) Ritual: Perspectives and Dimensions, New York: Oxford University Press. Bracken, Christopher (2007) Magical Criticism: the Recourse of Savage Philosophy, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Derrida, Jacques (1982) 'Différance', (Alan Bass, Trans.) Margins of Philosophy (pp. 1-27), Brighton, Sussex: The Harvester Press. Kreisler, Aaron (2011) 'Radiant Matter II', in Dane Mitchell (ed.) Radiant Matter I/II/III, Berlin: Berliner Künstlerprogramm/DAAD & ARTSPACE Auckland, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. Lévy-Bruhl, Lucien (1975) The Notebooks on Primitive Mentality, (Peter Rivière, Trans.), Oxford: Blackwell. Mauss, Marcel (1975) A General Theory of Magic, (Robert Brain, Trans.), London: The Norton Library. Plato (1991) The Republic of Plato, (Allan Bloom, Trans.), New York: Basic Books. 19 Saler, Benson (2003) 'Lévy-Bruhl, Participation, and Rationality', in Jeppe Sinding Jensen & Luther H. Martin (eds.) Rationality and the Study of Religion (pp. 44-64), London: Routledge. Tambiah, Stanley J. (1973) 'Form and Meaning of Magical Acts: A Point of View', in Robin Horton & Ruth Finnegan (eds.) Modes of Thought (pp. 199-229), London: Faber and Faber. Taussig, Michael (1993) Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of the Senses, New York: Routledge. Bio Chris Braddock is an artist and academic. He is Associate Professor of visual arts in the School of Art & Design, AUT University, New Zealand, and Chair of the AUT St Paul St Gallery. His art practice involves performance, video, sound and sculpture. See www.imageandtext.org.nz. His theoretical research employs key terms such as: animism, material trace, performance and photography/video, part-object/partsculpture, art and spirituality, blasphemy. This article is reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan. It reproduces sections of writing from: Braddock, Christopher (2013) Performing Contagious Bodies: Ritual Participation in Contemporary Art, London: Palgrave Macmillan. Braddock’s book explores live/performance art and installation practices through theories of magic ritual. It maps out a study of live art – together with its documentation and object/material traces – and uses the concepts of contagion, animism and ritual participation to open up a range of hotly debated questions about the temporal aspects of live art and their relation to ‘event’ and where ‘liveness’ lives. As such the book explores the intersections of performance studies, art history, anthropology and contemporary visual art practices. Performing Contagious Bodies dedicates full-length chapters to New Zealand artists Alicia Frankovich and Richard Maloy, and to Australian artists Laresa Kosloff and Alex Martinis Roe, together with discussion of a number of widely acknowledged Euro-American artists (Marcel Duchamp, Ann Hamilton, Bruce Nauman, Gabriel Orozco, Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Hannah Wilke). 20