Archival Thoughts In The Historical Archives Of A Transylvanian Town

advertisement

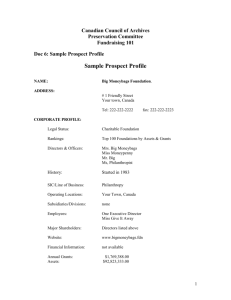

Archival Thoughts In The Historical Archives Of A Transylvanian Town Bogdan-Florin Popovici (Romania) Abstract The present paper presents the history of archives in an Transylvanian town: Brașov. The presentation focuses rather on the thoughts of archivists and administration about archives along centuries, and less on the institution itself. It started in 15th–16th centuries, with random collection of legal papers, continuing in 18th century with the first understandings of historical value. It carries on, with the dilemma of serving both the administration (mainly through registry) and the science (through archives itself). The second half of the 19th century bring history as an increasing relevant part of culture, and the tasks of archivist and registrar became more and more distinct. The formalize of historical archives of the town and the best practices used here proved to be respected no matter the political or national leadership. The paper ends with the moment when the town archives became the core of the regional Division of the State Archives—a tribute to the professionalism of the archivists here. 1. Introductory remarks Brașov (German: Kronstadt, Hungarian Brasso) is a city placed in the South Eastern inner corner of the Carpathians. Part of the historical region of Transylvania, it followed the general historical course of this territory: part of the Hungarian Kingdom (untill 1526), of the Transylvanian Principality (1526–1691), of the Habsburg/Austrian Empire (1691–1876), of Hungary again (1876–1918). After the WWI, it became the geographical center of Romania. The foundation of the town rests of German (Saxon) colonists, brought here by the king of Hungary, for economic and military purposes. Along centuries, the Saxons led the town administration. The first real shift occurred after WW I, when the administration became mainly Romanian. These historical remarks are to emphasize the fact that Brașov archives is the by-product of multicultural and multilateral administrations and communities. This aspect is very important, as long as the whole archival history of the town reflects the background of archivists who worked here or the regulations that affected the work with documents. 2. Beginnings There is no formal beginning for the town administration archives. Considering the fact that the oldest records preserved until today dates back to 1353, and a lot of charters and letters from 14th–15th centuries were preserved, we can reasonably assume that there was an interest to keep the records of the administration, even from the beginning. Where this archive was kept is not possible to find out for sure. We only know that in 1420, the town administration issued a document showing for the first time where the residence of Town Council was: in the middle of the town main square, in a building that, until today, it was known as “the Town Council Hall”. This is why it can be assumed that the town administration records and archives were also preserved in this building. It is also true, on the other hand, that the archive might have been kept at one clerk’s house… The first real news about the town archives dates from 22nd July 1476, when the notary (secretary) of the town wrote that he was not informed about a request of delivering older charters granted to local town administration; otherwise, he could deliver also some old charters, because “we might have different charters too in our chest about these things”1. From this text, several remarks can be made. Firstly, archives of the town existed, meaning that the administration of the town was aware of the importance of records and their preservation. We cannot say anything about the types of records preserved, but at least one type—charters—was included, showing the interest of preservation for juridical reasons. Secondly, the records were preserved in a chest, which has a twofold impact: security and maneuverability. Access to the administration records was not for everybody; as it looks like, it was the duty of the notary to preserve them and to access them when in need. On the other hand, a chest is easy to remove and transport when necessary (considering also the small amount of records existent in the town archives). All these shows again a high interest for preservation the records. On third remark is about the lack of finding aids or any other form of control (physical or intellectual) over those records. In one way, this is the most efficient way to secure the records, as long nobody would know for sure which charter serves for what, except for the case he would read them individually… The fact might reflect also two different views: one—that the amount of records was so small, that it was easy to retrieve when necessary. Even so, the lack of a finding aid deprive the owner of a good tool to secure the existent. On the other hand, it might be a lack of interest of investing effort to compile an inventory. As the last option looked more close to the fact, the general remarks would be an emphasis on preservation and lack of interest on proper and quick access to records. 3. 16th century: Christian Pomarius Over almost a century, the situation of the town archives seemed to change very few. Despite that, it seems that some practical experiences of open-minded people in administration make them to change their view over preservation of records. In this regard, the first known attempt to arrange and describe the records in Brașov archives belonged to Christian Pomarius2. Pomarius was notary in several other Transylvanian Saxon towns, prior to his arrival in Brasov. Invited to Brașov in 29 April1551 by the Town Council, it was immediately appointed as notary. In order to outline the mindset of this character who organized Brașov archives, a few remarks over his ideas on archives should be done. Pomarius noted that always in history there are memorable facts that should be recorded, therefore it is a duty for the administration of towns to record events, codes of laws or administrative decisions. This recordation should not only regard the kings and military leaders, but also significant facts done by ordinary people. Quoting Justinian, he said the records are important because “containing the will of monarchs and it fixes the laws”. Such an important matter needs tools of control, 1 Gernot Nussbächer, Contributii la istoria arhivei Brasovului în secolele XV-XVIII, în „Cumidava”, IV, Brasov, 1970, p. 559. 2 The historical information is based, if not otherwise referenced, on G. Nussbächer’s article Din activitatea arhivistică a lui Christian Pomarius, in “Revista Arhivelor”, 2/1965, p. 171-178. The comments about the historical facts belong to us. accordingly. For Pomarius, the inventories are very important; if they are read from time to time before the councilors, they allow memorizing the rights of the town and allow the decision-takers to act similar in similar situation. More, an inventory might serve as a replacement in case of lost or theft of the original. Both these arguments shows the view over inventories as a quick and reliable tool for intellectual (content) control over records, avoiding the use of the original or even replace them, if the case. Another reason for which the inventory is important for the quick retrieval of records in the repository (the physical control). For these reasons, Pomarius encouraged the multiplication of archival inventories. In Brașov, in 1552, it was built for the archive a cabinet with 27 drawers (literarum repositorium). It was most likely from Pomarius’ initiative, as long as the solution is very much similar with the one in Sibiu, another town where Pomarius was notary before. The records seemed to be arranged in drawers, on mixed criteria, by issuer and by topic3. For each topic of important issuer, Pomarius designed a group of records, with letters as reference codes (amount: 19 groups). This arrangement is explicated in the inventory. The inventory, preserved until today only as a copy, bear the title Litterarum Civitatis Coronensis digestio. Within the inventory, the 309 records are divided in 19 groups, all listed. About descriptive elements, the inventory contained for each document the abstract, designation of carrier, language, seals etc. In all descriptions the issuer and the date of documents are also listed. 4. 17th century: Martin Seewaldt After Pomarius, for more than a century, no other mentions about archival processing were preserved until today. The next attempt seemed to occurr at the end of 17th century, by the secretary Martin Seewaldt. The charters of the archives were again the focus. He arranged 338 records, grouping them in 12 groups, based on their issuer4. Despite the increasing number of records, it is significant that the documents evidencing legal rights are still the main target of archival processing. Also, because there are only 29 charters more that in Pomarius’ inventory, it would not have been necessary a new re-processing, except for the case the initial order was not preserved. This is very likely, mainly because of the damages produces during the Great Fire of the town, in 1689. 5. 18th century: Johann Albrich and… At the beginning of 18th century, town administration faced again new legal challenges and the Mayor of that time asked then documents that grounded the town legal rights to be produced. This would prove to be an impossible task for one person, because of the disarray of records in the archives. Therefore, he appointed his son-in-law, a 27 years old medicine doctor, Johann Albrich, former student in Halle, Leyden and Utrecht, to set a new arrangement of the town archives, in 1714. Albrich focus was, again, on the charters of the town, as the holders of the most relevant legal information. He took the records and started to write the abstract of documents on their backside, assign them numbers and arrange them in divisions in four cabinets, noted with letters, from A to D. The 3 This is the actual state of research. In fact, it might be likely that the only criteria is topical. The historical information is based, if not otherwise referenced, on G. Nussbächer’s article, Contribuții…ș see also Gernot Nussbächer, Sisteme de arhivare înainte de introducerea sistemului de registratură în unele arhive orăşeneşti din Transilvania, în Culegere de referate. Sesiunea 1969, Bucureşti, p. 143148. 4 main criteria was the title of the issuer. As a result, the records were grouped in four sections: the kings of Hungary, the princes of Transylvania, the rulers (“voievod”) of Transylvania and those from the Chapter in Alba Iulia (Klausenburg, Gyula-Fehérvár) and the Convent in Cluj Mănăștur (Kolozs Monostor, Klausenburg), the locca credibilia of the time5. Within these two sections, all the records were arranged based on the specific issuer. He started then, with some help from different studiosi academici, to copy the content of many important charters in to a big register (codex), called Palladium Coronense (“the shield of Brașov”). The volume, a “security copy” avant la lettre, was going to be filled in up to 18656. All along with the reproduction of the content of records, he started to compile a new finding aid, called Index Generalis Literarum Privilegiorum. This finding aid seems to reflect the physical order of the records. The description of records contained consisted of the reference code (issuer and running number of records within the group of records coming from that issuer), then abstract of the record, the carrier and the seal, and in the end—the year of issue7. In the foreword of the two volumes, Albrich noted also his view on archival work. The copy of the content of records in Palladium was very useful, he said, for many reasons. Firstly, it will be easier for the registrars to find the records, to set them back and preserve them. Secondly, it would be superfluous to read the records themselves—it is enough to read the codex. Thirdly, it is useful for those who want to learn about the history of the town, under various aspects. Also, it would be the source of inspiration for politicians, to learn and to understand the past decisions, in order to properly decide for the future. Then, such a codex is useful because it can be used as a replacement of the original, when the latters are lost or damaged. He conclude that Palladium should not be free accessible, but restricted in favour of those who have the authority to read, correct and seal it8. About the finding aid, Albrich noted it was not completed. He asked the followers to index all the other records too, that are in a complete disarray, about the debts and payment of the town. They should be checked seriously, selected those useless, arranged the valued ones based on the issuer or the topic and aggregated them in bundles. A summary of bundles should then be added to the finding aid. The use of all this work would be mostly for the legal matters9. 6. …Georg M.G. von Hermann Despite this work, Albrich’s advices for the future were not followed. An archivist for the town archives was constantly appointed in the next years, but with no, or little effect. Albrich’s finding aid seemed to be lost until the middle of 18th century. Anyway, except for the old charters, the other records were not arranged and, by their number, the latter started to overwhelm the former ones. Under these circumstances, Georg Michael Gottlieb von Hermann was appointed as archivist in 1764. He started to arrange the records and to separate new records from the older ones. He used for arrangement a pigeonhole cabinet, and such, “in less than a year, without having a proper finding aid, I 5 Brașov County Archives, fond Brașov Town council, preface to the Palladium Coronense. Special thanks to Mr. G. Nussbächer for the translation provided of the Latin text into Romanian. 6 Nussbächer, Contribuții… 7 Ibidem. 8 Brașov County Archives, fond Brașov Mayor’s Office, preface to the Palladium Coronense. 9 The Evangelic Church Archives, collection Trausch, T.F.22, preface to the Index generalis. Special thanks to Mr. G. Nussbächer for the translation provided of the Latin text into Romanian. could loan upon request the new records, that were the most used”10. He used the arrangement based on alphabetical (topic or persons name involved) or chronological order. For some specific type of records, some alphabetical indexes were produced11. His diligent work of reading and summarizing records content was obvious in his exceptional historical work12, based mostly on the documents in the town archives. Then, Hermann re-arranged the charters for a proper retrieval. Firstly, he arranged them on issuer base and compiled the Index Privilegiorum…, as a finding aid. After few years, he re-arranged some charters, based on date of issue. This chronological arrangement was mirrored in a new finding aid, Consignatio privilegiorum… For the latter finding aid, P. Plecker edited an alphabetical index in 178413. As a curiosity, we should mention a bundle of juridical documents from Hermann, that were appraised as ”no valued”, but preserved “for curiosity or genealogy”. It would be the first known attempt of appraising in Brașov town archive14. In the following decades, the archival work within the administration tends to change. From 1 September 1772, the registry system was introduced in Brașov town administration15. Some classification were attempted (for instance, in 1786, besides “regular” records, there were two series, P and J (for political and legal affairs)), but did not last. Therefore, until later in 19th century, the new arrived records will be arranged based on their registration number. This new system will introduce a break, first subtle, then clearer, in archival tradition, and a shift between “old archive” and “new archive” (the one after 1772) was obvious. While older records needed criteria, arrangement and description, the new ones came naturally, by registration, indexation and arrangement based on their number16. Despite the fact that archivist was still involved in registration activities, this shift will became more and more obvious in the following years, and the difference of management between older and newer records make the administration aware of the specificities. The next decades will show an orientation of the archivist towards new records and only in the first half of the 19th century, with the advent of historical interest, turn the archivist back to the older archive of the town17. In 1785, Instructions for the town archivist were issued. This document outline the main ideas in the age about the archives of the town. The role of the town archive was to preserve public records of the town administration, but also some private person’s ones, stored in here for a safer preservation. The archivist had to keep a proper arrangement of records, then to create finding aids (indexes and other 10 Nussbächer, Contributii…, p. 569. G. Nussbächer, Arhiva orasului Brasov la sfârsitul secolului al XVIII-lea, in “Revista Arhivelor”, nr. 1/1993, p. 43-51. 12 G. Herrmann, Das Alte und Neue Kronstadt (vol. 1: 2010, vol. 2: 1883, vol.3: 1886). 13 Tiberiu Coliban, Colecțiile de documente întocmite în trecut în arhivele brașovene, in „Cumidava”, IV, Brasov, 1970,p. 547. 14 G. Nussbächer, Preocupări de evidență contemporană şi de prelucrare arhivistică la Braşov în secolele XVI–XIX. Contribuţii noi la istoria arhivei. Braşovului, in Ştefan Meteş la 85 de ani, Cluj Napoca, 1977, p. 161–165. 15 Franz Zimmermann, Ueber Archiv in Ungarn, Hermannstadt, 1891, p. 82-84. 16 This is only a theoretical view. In fact, an inquery from 1794 showed a lot of missing records in the archives. Also, it was obvious a need for proper indexes and some archivists started to compile their own (like Johann Joseph Trausch and his son, Joseph Franz Trausch). 17 See also, G. Nussbächer, Arhiva Brasovului la începutul secolului al XIX-lea, în “Arhiva Româneasca”, Tom I, Fasc. 1/1995, p.47-53. 11 tools) and to number the records. It is relevant that the first obligations for an archivist were to keep the existent arrangement and to include in this previous order the new entered records. Further on, the most protected records must have been those protecting legal rights of the town. Documents in archive should be protected against unauthorized access and deliverance; the latter could be possible only with permission from the Mayor, and a dummy should replace the document while loaned. A special remark was about the place of archive that should have been the house of Council and not the house of archivist. Some special sections in the archives must be created for economic or legal records, or for “deposits” from individuals, with a separate finding aid. An interesting interdiction refers to selection of records—the archivist might not appraise any record, no matter how insignificant, but to classify them properly18. 7. 19th century. Registrary vs. archives A few decades later, after many efforts to organize the archive of the town19, in 1812 it seems the archives received a new classification framework. The main sections were 1. Protocols (and subseries for each creating office); 2. Indexes (also with subsections on originating offices); 3. Contracts for rental, evaluations (on economic brances: mills, mountains etc.); 4. Charters and older records; 5. Mortificatoria — records concerning debts extinction; 6. (missing); 7. Papers about Dieta; 8. Miscellaneous. As it can be seen, there are no consistent criteria. The records were arranged based on format and, when this is not useful anymore, the topical criteria is used. But the large variety of records made it difficult to find the proper classification. The increasing number of records (20 documents in 1700, 3660 in 1800, 9230 in 1850) raised the question of the aggregation of records, for a proper management. Eventually, the system based on registration number continued to be used until the end of century, despite some attempts to create “files” (cumulus) after 185020. From many attempts to arrange the archive, the most relevant on the archival ideas level are those made by some archivists of the town who tried to deal with old records, other than the charters, and to group them together based on various criteria. In this regard, it should be quoted the actions of Eduard von Fronius, who acted as archivist between 1818–1819. He collected some older records, less important than charters, and bound them together in two volumes. Inside each volume, Fronius intended to arrange the records chronologically21. The same approach belonged to Friederich Schnell, who compiled three volumes of records, chronologically arranged. These two archivists showed their interest for history and answered to the increasing awareness of researchers in this field22. At the end of 1844, the same Fr. Schnell asked for the permission of disposal of “useless” records. The main reason was the lack of space for new records. From Schnell point of view, useless records were those “those which nor in farthest future will not serve as evidence or legal records”23, and they were 18 Nussbächer, Arhiva orasului Brasov la sfârsitul secolului al XVIII-lea, loc. cit. Nussbächer, Arhiva orasului Brasov la sfârsitul secolului al XVIII-lea; G. Nussbächer, Arhiva Brasovului la începutul secolului al XIX-lea, loc. cit. 20 G. Nussbächer, Arhiva Brasovului la începutul secolului al XIX-lea, loc. cit. 21 Ibidem. 22 Fr. Zimmermann, Das Archiv der Stadt Kronstadt in Siebenbürgen, “Archivalische Zeitschrift”, 5 (1880) p. 106-117. 23 G. Nussbächer, Arhiva Magistratului oraşului Braşov, în al doilea sfert al secolului al XIX-lea, in “Revista Arhivelor”, 2/1997, pp. 37-46 19 supposed to be appraised by a commission. The request was denied, after a large controversy, when even the idea of elimination of parts of records older than 25 years and sell them as waste paper. About the use of records, it must be noted a change of behavior from the administration. If, until 1845, the records had been loaned to the users, since then, the Council of the town was the only authority to advise the loan outside the archive and strictly forbade the loan to private persons. Also, it must be noted that during the events in 1848, the most important part of the town archive was evacuated in Sinaia (Walachia) in order to be protected by insurgences troupes that occupied Brașov24. 10. The end of 19th century: Friederich Stenner After the introduction of modern institution of state and local authorities, after 1872, some new developments took place also in what concern management of records and archives in Brasov. In a fortunate coincidence, all along this time (1878–1903) archivist of the town was a young scholar, Friederich Stenner (b. 1851). He studied Law at Graz and Budapest universities and, after being appointed as archivist, he attended a three-month training course in Sibiu (Hermanstadt), taught by Franz Zimmermann25. Zimmermann, at his turn, graduated Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung in Wien and studied the archival system in Munich and Graz26. The new statute of the town27 determined the local administration to issue a new Regulation for the town administration as well. In the section concerning the archive, some new provisions were inserted, changing the way archives worked until then. Firstly, following a trend visible from the end of 18th century, the registry and the archives are now two separated entities. Copying the obvious German model of Registratur and Archiv, this new system was an absolute necessity. The increasing number of records (9230 in 1850, 11 666 in 1878), the continuous increasing demand of historical documents for research made obvious the need for separate (offices active and passive archive), bearing separate mandates. About the activity of registry, the Regulations makes explicit the change from chronological to topical system of filing records28. With the contribution of Fr. Stenner29, the system became a smooth and effective one. A document was registered and, based on its content, it was assigned to a certain file. The file was classified using a filing plan of 4 (afterwards, 6) classes. The file reference code was from 1 to n within corresponding class. The document subjects and topic were recorded in indexes of (person) names and topics. On the front cover of each file, all the records within were listed, with their registration number, abstract and number of annexes. The running number on the cover determined the document number of order within that file. Finally, another tool made the connection between the file 24 Ibidem. See also idem, Arhiva magistratului oraşului Braşov între 1851-1861 in “Revista Arhivelor – Cluj”, ClujNapoca, 1-2/1995, 1, p.15-23. 25 G. Nussbächer, Prețuitori ai arhivelor: Friederich Stenner, arhivarul orașului Brasov, in “Revista Arhivelor”, 2/1978, p. 204-206. 26 Fritz Sonntag, Franz Zimmmermann, în Figuri de arhiviști, București, 1971, p. 242, 244 27 Gemeindestatut des Stadt Kronstadt, Braşov, 1878, # 104–125; See also E. Marin, Instituţionalizarea arhivei istorice a oraşului Braşov (1879) in "Acta Bacoviensis”, I, 2006, pp. 26-28; Peter Moldovan, Privire retrospectivă asupra Arhivelor orăşeneşti Sibiu, Bistriţa şi Braşov in “Revista arhivelor”, 1/2009, pp. 86–89. 28 See Marin, Ibidem 29 Archives of Evangelic Community Brașov, Fr Stenner—Familien chronik (mss)., vol. 1, p. 26-27 code and the document number. In this way, access points could be document number, name of person, name of topic, and all the documentation pertaining to a topic was aggregated together. The Archive started after 60 years of current and semi-current use30; it was a change thinking that, at the beginning of registry system, the transfer to passive archives occurred when the cabinets of the new archive as filled up31. The Archive had many functions. The first one was to preserve and maintain the arrangement for all the written goods it holds and to classify the current records in the proper files. Several tasks consisted in checking if the person who require a certain document has the right to use it and, if so, and if the document is loaned, the archive staff should follow its restitution. The archive had also the mandate of issuing certified copies from the records held. By the rules for Archives in 1881, the historical archive of the town was organized on the following sections: 1. Old documents; 2. Recent documents; 3. Accounts; 4. Protocols; 5. Indexes; 6. Private papers; 7. Library of the Archives. In 1903, 4 more sections were added: 8. Plans and maps; 9. Deposits; 10. Surveys and 11. Museum objects. These sections were almost similar with those used in Sibiu by Franz Zimmermann32. Stenner continued the work of this two predecessors, Fronius and Schnell, and made a collection of old records found in the archives, based on the criteria of language. From 1903, in the last year Stenner worked as archivist (before being elected local councelor), dates a set of rules for the reading room of the Brașov town archives33. The Archive could be used for “scientific purposes” by any researcher who had a research card, issued yearly by the Mayor of the town. The purpose of research should be indicated. The access to “confidential” records could only be granted by an “archival commission”. All the research should have been carried out inside the reading room, the loan of records at home being forbidden. An interesting provision is that, if anyone would damage the record, he/she would have been publicly exposed in the official publication of the Mayor’s Office…. 11. Beginning of the 20th century. Tradition and continuity In 1903, Stenner left the Archives, but the coordinates of his work for Registry and Archives remained the same. Moreover, from his position, as town councillor, he remained close to his first job. In this respect, it must be noted his endeavours for an appraisal and disposition of records from the Archives34. In 1918, he proposed an appraisal for the records, to be undertake by the offices of origin. Despite the rejection of his proposal, he insisted the next year, but only in 1920 his proposition was accepted. He was the person who effectively was supposed to select the useless records, but he will present the results in front of an administrative commission, that will decide in the end. The legal ground would have been the Hungarian Law 20 from 1901. We do not know now if the selection took place or not. The integration of the province of Transylvania and, also, of the town Brașov into Romania, after WWI, brought some changes in the way administration works. For instance, in 1925, a ministerial order 30 Brașov County Archives, fond Brașov Mayor’s Office, Series Magistrat Records, no. 4697/41903 Nussbächer, Arhiva orasului Brasov la sfârsitul secolului al XVIII-lea, loc. cit 32 Fr. Zimermann, Das Archiv der Stadt Hermannstadt und der Sachsischen Nation, Sibiu, 1887. 33 Brașov County Archives, fond Brașov Mayor’s Office, Series Magistrat Records, no. 4697/1903. 34 E. Marin, Arhiva Brașovului în anii 1916-1920; 1936. Arhivarul Fritz Schuster (1916-1927), in "Cumidava", 27 (2004), p. 238. 31 changes the way registry worked35. The ground for a file was not the first record pertaining to a topic (as before), but the last one. The 6 classes for filing records became 29, with other criteria for division. We have no contemporary remarks about this system, but today, when trying to retrieve records from that time, it is a huge discrepancy between the effective and precise system introduced by Stenner, and the strange system introduced in 1925. Despite such unfortunate measures, the lines of the tradition were preserved. In this regard, in 1930, the local administration issued some new Regulations, both for the Registry and for Historical Archive of the town36. The registry of the town was unique for all branches of local administration. Its role was to register, to track and to handle records, for the effectiveness of local administration. The main goal of the town Archives, on the other hand, was to serve for Mayor’s office business, but also the scientific research. The Archive could acquire: historical records; records from the local administration older than 15 years, that "are no longer needed for current business and that will be preserved and arranged based on the principle of provenance"; seals, heraldry of the town, official publications. The Archives could make collection of any records pertaining to the history of the town. Researches could be carried out only in the building of the Archives. Before starting the research, a person should sign a statement about obeying the rules for the reading room, and a dummy for each record loaned. The researchers should pay a fee (daily or monthly) for their access to the reading room. Despite the interdiction to loan records outside of the Archives, in special circumstances, for trustable institutions, this could be possible for maximum of 6 months. The access to records was free, except for the records later than 1918, where the Mayor approval was necessary. The Archives was allowed to dispose records only by observation of Archival law and Accountability law. The chief of the Archives had the obligation to periodically publish finding aids, to make contacts with similar institutions abroad, to organise a permanent exhibition with reproduction of the archival and library material. The proper care and interest of local administration for the records, both active and inactive, was appreciated in the age. In this regard, the Mayor’s office had the moral authority to decline the legal obligation for concentrating historical archive of the town to the Regional Archives in Cluj37. Also, in 1935, valuable collection of old records taken in 1916 from town Archives by the retreating Romanian Army, and then evacuated to Moskow, were returned in 1935, somehow contrary to the centralisation trend of time38. Finally, in 1939, the town archives became the core of Brașov Regional Division of the State Archives39, a tribute paid to the professionalism of the institution and its workers. 12. Conclusions The archives of Brasov lasts for more than six centuries. The great advantage of learning its history is that it gives as valuable lessons about the nature of archives, about the evolution of its management and human interests towards it. 35 Brașov County Archives, fond Brașov Mayor’s Office, Series Magistrat Records, no. 5989/1925. Published in “Monitorul municipiului Brasov”, 1930. 37 E. Marin, Fritz Schuster—arhivarul orasului Brasov, 1916-1927 in "Revista Arhivelor", 1-2/2004, p. 244-245. 38 E. Marin, Arhiva Brașovului în anii 1916-1920; 1936…, p. 238-239. 39 “Monitorul oficial”, I, nr. 89/18.04.1939, p. 2379. 36 One lesson learnt is that people did not care, in first place, about recording their past, except for those recordings that might help in future, from legal point of view. Furthermore, they did not care to properly arranged records; keeping them seems enough, as long as when needed, they are available. Another lesson is that open-minded people understood from centuries the need for finding aids. One may have the records, but, as long as one does not know you have it, it is like one has not them. Those “visionaries” did their job, but one arrangement is not good enough, because the harder part is to maintain the proper order. Which is always harder than just to keep the records. The “passion” to keep the records stops instantly when that preservation starts to cost too much. And then a great and instinctive temptation to throw away the “garbage” is very hard to stop. The problem shuld be solved, but other centuries lasted until the rational appraisal and elimination become a fact. On the other hand, it took a very long time for people to understand that records can be arranged in many ways; a fight for the perfect order can be un histoire sans fin. What about respecting the provenance?... A good care for records seems to reflect the level of civilization of a community. Unfortunately, this is only a by-product of civilization and not a milestone in itself. It just happens, naturally, to take care about the Past. Because you have it.