Bodies of Flesh, Bodies of Knowledge

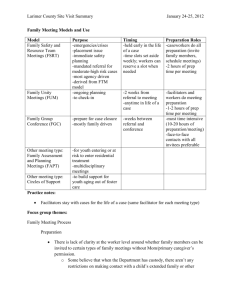

advertisement