(FGC), commonly called female genital mutilation

advertisement

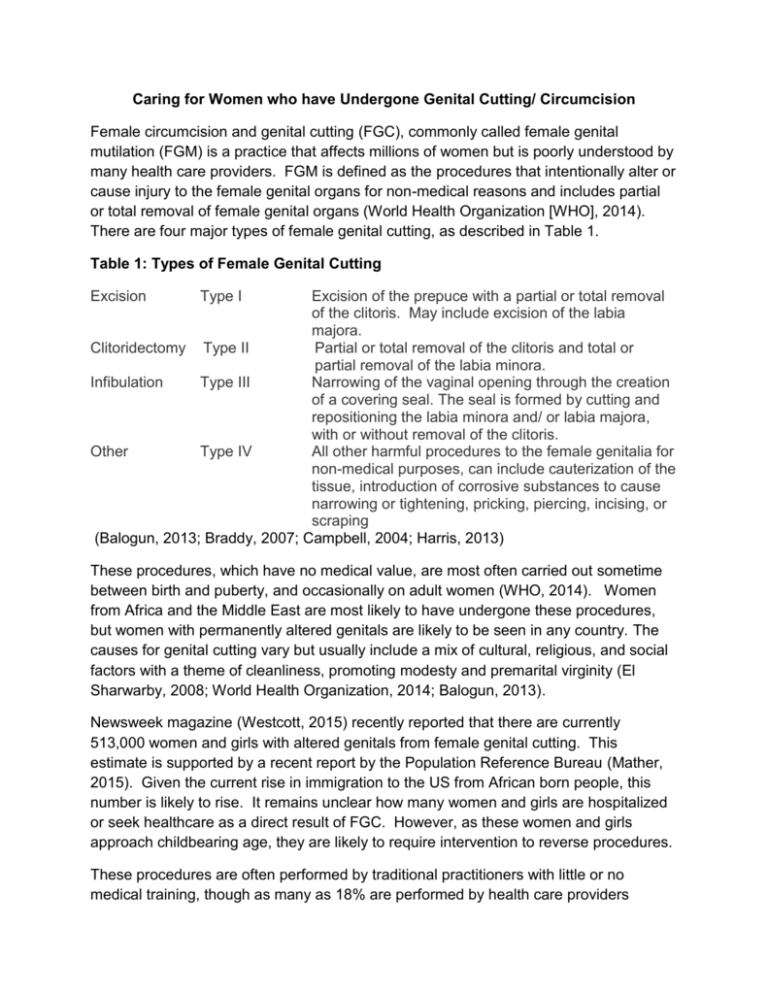

Caring for Women who have Undergone Genital Cutting/ Circumcision Female circumcision and genital cutting (FGC), commonly called female genital mutilation (FGM) is a practice that affects millions of women but is poorly understood by many health care providers. FGM is defined as the procedures that intentionally alter or cause injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons and includes partial or total removal of female genital organs (World Health Organization [WHO], 2014). There are four major types of female genital cutting, as described in Table 1. Table 1: Types of Female Genital Cutting Excision Type I Excision of the prepuce with a partial or total removal of the clitoris. May include excision of the labia majora. Clitoridectomy Type II Partial or total removal of the clitoris and total or partial removal of the labia minora. Infibulation Type III Narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal. The seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the labia minora and/ or labia majora, with or without removal of the clitoris. Other Type IV All other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, can include cauterization of the tissue, introduction of corrosive substances to cause narrowing or tightening, pricking, piercing, incising, or scraping (Balogun, 2013; Braddy, 2007; Campbell, 2004; Harris, 2013) These procedures, which have no medical value, are most often carried out sometime between birth and puberty, and occasionally on adult women (WHO, 2014). Women from Africa and the Middle East are most likely to have undergone these procedures, but women with permanently altered genitals are likely to be seen in any country. The causes for genital cutting vary but usually include a mix of cultural, religious, and social factors with a theme of cleanliness, promoting modesty and premarital virginity (El Sharwarby, 2008; World Health Organization, 2014; Balogun, 2013). Newsweek magazine (Westcott, 2015) recently reported that there are currently 513,000 women and girls with altered genitals from female genital cutting. This estimate is supported by a recent report by the Population Reference Bureau (Mather, 2015). Given the current rise in immigration to the US from African born people, this number is likely to rise. It remains unclear how many women and girls are hospitalized or seek healthcare as a direct result of FGC. However, as these women and girls approach childbearing age, they are likely to require intervention to reverse procedures. These procedures are often performed by traditional practitioners with little or no medical training, though as many as 18% are performed by health care providers (WHO, 2014). When performed by a traditional practitioner, instruments such as razor blades or glass may be used, with or without anesthesia (El Sharwarby, 2008). Women and girls residing in the US are often sent back to their home country to undergo FGC a practice known as vacation cutting (Westcott, 2015). Whether performed by traditional practitioners or health care practitioners, these procedures are associated with significant medical risks. Long and short term consequences are described in Table 2. Table 2: Long and Short Term Consequences of Female Genital Cutting SHORT TERM CONSEQUENCES LONG TERM CONSEQUENCES Death Abscesses Fractures of clavicle, humerus or Cyst formation femur from restraints during the Depression procedure Dysmenorrhea Hemorrhage Dysuria Infection Higher incidence of cesarean delivery Injury to adjacent tissues such Incontinence as urethra or bowel Increased risk for HIV due to Pain increased friction, abrasions, and/ or Sepsis skin tears during sexual intercourse Shock (due to hemorrhage or Infertility as a result of ascending vaso-vagal reaction) infection in the genital tract Urine retention Keloid scarring Loss of sexual desire and ability to achieve orgasm Maternal death Painful intercourse Pelvic inflammatory disease Perineal tears in childbirth Post-partum hemorrhage Post-traumatic stress disorder Prolonged and obstructed labor Rectovaginal fistula Recurrent bladder and urinary tract infections (Braddy, 2007; Frega, 2013; Harris, 2013; Lundberg, 2008; Paterson, 2012; Reyners, 2004; Vloeberghs, 2012; World Health Organization, 2014) The vast majority of articles about female genital cutting focus on stopping these practices. Most use negative terms such as mutilating or mutilation to describe the procedures, as does the World Health Organization. An estimated 125 million women have undergone these procedures (World Health Organization, 2014), often as children. As adolescents and adults, these women require medical care from health care professionals who can provide safe and culturally sensitive care. Healthcare interventions for women and girls who have undergone genital cutting are most likely to include deinfibulation, episiotomy, removal of cysts, treatment of infections, and counseling. During antenatal care, healthcare providers may dissuade women and their partners from undergoing reinfibulation after childbirth (Balogun, 2013). When they have relocated to a country where these surgeries are less common, locating culturally sensitive care can be difficult. While the term, genital mutilation is accurate for policy makers and human rights activists (Braddy, 2007), it is judgmental and potentially harmful for women whose genitals are permanently altered, particularly when used by someone outside of their own culture (Braddy, 2007; Odemerho, 2012). The idea of FGC may elicit feelings of shock and horror, making these women reluctant to seek medical care or to disclose their condition to their provider. One third of women with FGC reported symptoms of depression and anxiety in a study conducted in the Netherlands (Vloeberghs, 2012). These feelings of depression and anxiety were intensified during childbirth or when suffering from physical problems. These women felt ashamed to be examined by a physician and avoided visiting providers who failed to conceal their shock about the woman’s appearance (Vloeberghs, 2012). Women who fear embarrassment, humiliation, or judgment from their healthcare provider may delay essential medical care (Braddy, 2007; Odemerho, 2012). Thus, it is important that the health care provider is culturally competent in their provision of care. Suggestions for culturally competent care of the woman with FGC are outlined in Table 3. Table 3: Culturally Competent Care Use nonjudgmental words (female circumcision, female genital surgery) and approach to the interview and exam. When in doubt, use the term used by the woman or ask her about the preferred term. Don’t act surprised, disgusted, sad or shocked upon seeing the perineum. Focus on the care needed rather than the circumcision. Provide an interpreter as needed Refrain from making assumptions about sexuality of the woman. Provide privacy and confidentiality; don’t call in colleagues to look at the perineum. Use a standardized tool to assess the type of procedure the woman had and any complications she has experienced as a result. The woman may not attribute complications to the procedure – ask about specific conditions, not what she has experienced as a result of the procedure. This worksheet can be located in: “Care of Women with Female Circumcision,” by C. Campbell, 2004, Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 49, p.365. Use a pediatric speculum for exams. If the introitus is too small to accommodate the speculum, a bimanual exam with the use of 1 to 2 fingers, including a rectovaginal examination is recommended. (Braddy, 2007; Campbell, 2004; Odemerho, 2012; Vloeberghs, 2012) A comprehensive look at FGC is beyond the scope of this article. However, there are a number of helpful resources for clinicians who wish to understand more about providing optimal care for women who have undergone these procedures. Table 4 provides a partial listing of resources for health care providers. Table 4: Resources for health care providers caring for FGC patients The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Female Genital Cutting: Clinical Management of Circumcised Women (2nd Ed.) This is a multimedia kit designed for health care providers and includes slides, speakers notes, objectives, and resource listing. Available at: http://sales.acog.org/Female-Genital-Cutting-Clinical-Managementof-Circumcised-Women-Second-Edition-P349.aspx Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Green-top Guideline No. 53 – Female Genital Mutilation and its Management. Available at: https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/greentop53femalegenitalmu tilation.pdf The World Health Organization Female Genital Mutilation Teachers Guide to Integrating Prevention and Management of the Health Complications into the Curricula of Nursing and Midwifery. Available at: http://www.who.int/gender/other_health/teachersguide.pdf The FGM Report – Canadian Women’s Health Network. Available at: http://www.cwhn.ca/sites/default/files/resources/fgm/fgm-en.pdf FGC is an important and culturally sensitive issue for an increasing number of women seeking obstetric and gynecologic care in the United States. It is important that health care providers seek to understand the cultural beliefs and values of women who have undergone these procedures and provide informed and sensitive care. REFERENCES Balogun, O. H. (2013). Interventions for improving outcomes for pregnant women who have experienced genital cutting (Review) . The Cochrane Collaboration . Wiley. Braddy, C. (2007). Female genital mutilation: Cultural awareness and clinical considerations. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health , 52(2), 158-183. doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.11.001 Campbell, C. (2004). Care of women with female circumcision. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health , 49, 364-65. El Sharwarby, S. R. (2008). Female genital cutting . Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Reproductive Medicine, 18(9), 253-55. Fahs, B. (2014). Genital panics: Constructing the vagina in women's qualitative narratives about pubic hair, menstrual sex, and vaginal self-image. . Body Image, 11, 210-218. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.03.002 Frega, A. P. (2013). Obstetric and neonatal outcomes of women with FGM I and II in San Camillo Hospital, Burkina Faso. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 288, 513-519. doi:10.1007/s00404-013-2779-y Harris, T. (2013). Female genital mutilation: A literature review. Nursing Standard, 28(1), 41-47. Lundberg, P. G. (2008). Experiences from pregnancy and childbirth related to female genital mutiliation among Eritrean immigrant women in Sweden. Midwifery, 24, 214-225. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2006.10.003 Mather, M. &.Feldman-Jacobs, C. (2015, February). Women and girls at risk of female genital mutilation/ cutting in the United States. Retrieved from Population Reference Bureau: http://www.prb.org/Publications/Articles/2015/us-fgmc.aspx Odemerho, B. B. (2012). Female genital cutting and the need for culturally competent communication . The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 8(6), 452-57. doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2011.10.003 Paterson, L. D. (2012). Female genital mutilation/ cutting and orgasm before and after surgical repair. Sexologies, 21, 3-8. doi:10.1016/j.sexol.2011.09.005 Reyners, M. (2004). Health consequences of female genital mutilation. Reviews in Gynaecological Practice, 4, 242-251. doi:10.1016/j.rigp.2004.06.001 Vloeberghs, E. V. (2012). Coping and chronic psychosocial consequences of female genital mutilation in the Netherlands. Ethnicity & Health , 17(6), 677-695. doi:10.1080/13557858.2013.771148 Westcott, L. (2015, February 6). Female genital mutilation on the rise inthe US. Newsweek. Retrieved from http://www.newsweek.com/fgm-rates-have-doubledus-2004-304773 World Health Organization. (2014, February). Female Genital Mutiliation. Retrieved from WHO Media Centre: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/