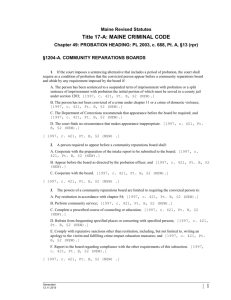

Justice requires reparations to Black Americans.

advertisement