Bruno Blondé & Wouter Ryckbosch

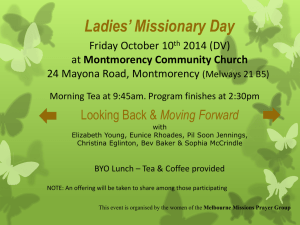

advertisement

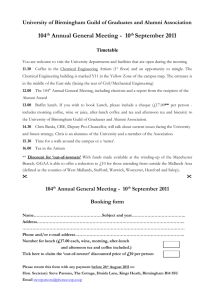

Arriving to a Set Table: The Integration of Hot Drinks in the Urban Consumer Culture of the Eighteenth-Century Southern Low Countries Bruno Blondé & Wouter Ryckbosch Introduction This chapter aims to explore some of the ways in which the rapidly expanding consumption of sugar and hot drinks during the Eighteenth Century impacted upon the material culture of urban households in the Southern Low Countries. The swift and widespread adoption of the domestic consumption of hot drinks, along with a variety of accompanying utensils and consuming practices during this period, has by now become a well-established historical finding. Relative prices and trade patterns have been substantively documented,1 and so are the manners in which tea and sugar altered European ways of life, for instance by influencing patterns of domesticity and sociability during the early modern period.2 In many towns of the Southern Netherlands, the introduction of colonial goods transformed the structure and timing of meals, and profoundly influenced existing patterns of sociability.3 Yet, while a lot is known about the social and cultural practices of coffee and tea use, and even more is often suggested, important questions still need to be answered concerning the impact of this impressive shift in consumer tastes upon material cultural and consumer behaviour at large. Hot drinks and other ‘exotic’ groceries such as sugar and tobacco are usually—either implicitly or explicitly—attributed a key role in the emergence of a new consumer mentality in eighteenth-century Europe. This, at least, seems to be the opinion of Sidney Mintz when (concerning sugar) he claimed that ‘the very nature of material things must have seemed to change, as commodities, in the new capitalist sense, became commonplace’.4 A central argument in Mintz’ 1 narrative is the large social reach of global groceries: sugar and hot drinks quickly gained status as ‘popular’ luxuries. Jan de Vries, among others, has elaborated upon this idea. In a recent synthesis of his demand-side approach to explaining early modern economic growth, colonial groceries were given a prominent place in changing eighteenth-century consumer patterns, and especially in triggering the growth of the retail revolution and the allocation of household time to marketoriented activities.5 In this sense, the growth of hot drinks consumption contributed significantly to the expansion of the retail sector and the need to purchase things on the market, and in so doing perhaps triggered an ‘industrious revolution’. Indeed, as Anne McCants observes, ‘there is a widespread agreement among European historians about the magnitude of the cultural ramifications of hot (sweetened) caffeinated beverage consumption.’6 This chapter nevertheless intends to add a modest contribution to this larger debate by questioning whether colonial groceries played a significant role in the emergence of a more modern ‘consumer mentality’ through changes in material culture. This will be attempted not so much by focusing upon the actual consumption of hot drinks, but rather by approaching the larger material culture surrounding the advent of these colonial beverages. Some authors, including Carole Shammas, have seen in the formation of a genuine ‘hot drinks culture’ both a symbol of, and a causal factor in a profound shift in the eighteenth-century domestic environment. The growing popularity of ceramic tableware, drinking vessels and smoking pipes as well as glass, involved a general transition from sturdy durables to a more decorative but also more disposable domestic material culture.7 In other words, durable consumer goods became less important for the economic capital they embodied, and more important in terms of their symbolic value as markers of status and identity.8 This process, which was been summarised in Jan De Vries’ distinction between ‘old’ and ‘new luxuries’ had important consequences in bringing about a more commercialised and mass-consuming society.9 It would obviously lead us too far to elaborate upon the causes and consequences of this larger transformation, but in the following pages we will 2 at least try to find out to what extent this shift was facilitated or even caused by changing drinking habits. The argument is based on the analysis of probate inventories in two rather distinct urban communities in the eighteenth-century Southern Netherlands: the commercial port city of Antwerp (in Brabant), and a secondary, provincial town of only regional importance: Aalst (in Flanders). The case of Antwerp might not be exemplary for north-western Europe at large. Although after 1585 the city was deprived of an autonomous maritime network, it still managed to become the seat of the headquarters of the ‘Ostend Company’ in the early Eighteenth Century—the only important (albeit short-lived) company for east-Asian trade the Austrian Netherlands ever possessed of.10 Thanks to this privileged relationship with the Ostend Company, Antwerp can be viewed as an excellent— though perhaps slightly atypical—test case for the impact colonial groceries exerted upon consumer culture in the Southern Netherlands. As a counterexample the much smaller provincial town of Aalst (app. 8000 inhabitants), situated in the heavily proto-industrialized countryside of inland Flanders, shall be studied as well. Probate inventory evidence will be used in describing patterns of consumer innovation and changes in material culture. The probate inventories examined for Antwerp stem from notary records of the municipal archives, while those from Aalst were drawn by order of municipal aldermen. In both places not all households complied with the customary rules concerning probate; and since inventories were costly, they were rare among the poor.11 In order to account for the differential social composition of the inventory samples, we examine two distinct social groups: the poor and labouring classes, and the middling groups and above. These have been formed by first ranking the inventories according to socioeconomic position—based on the number of rooms in the case of Antwerp, and based on the fiscal value of the house inhabited in the case of Aalst—and subsequently making a cut point from the point where master craftsmen and retailers become a 3 sizeable share in the distribution. This was the case for inventories comprising four rooms or more in the case of Antwerp, and inventories from the 40th percentile upwards in the case of Aalst. The adoption of hot drinks in the Southern Netherlands After the death of Johannes Ebbers in 1779, the Antwerp notary drawing up his probate inventory had little work to do. Indeed, Johannes was a relatively poor grave-digger. As a bachelor he occupied but one room, which he rented on the Veemarkt (cattle market) in Antwerp. Johannes possessed only few objects made in pewter, let alone precious metals. Yet, he owned a small collection of earthenware and porcelain goods. Moreover, in his lifetime he was—if he ever enjoyed the pleasure of receiving guests at home—capable of serving them a cup of coffee.12 Financially speaking, Tobias van Belle, an impoverished baker in Aalst whose wife died in 1791, was probably not much better off than Johannes Ebbers. Living together with his two daughters in a rented house, his humble bearings clearly did little to impress the town officials of Aalst, since his inventory was recorded free of charge. In terms of net wealth, his household belonged to the poorest 10 per cent of the 1790s inventory sample. However, despite this relatively precarious financial situation, the consumption of hot drinks was not considered an unaffordable luxury. Among the items found in his kitchen were eight teacups and saucers, a teakettle and two coffeepots—one made out of copper and the other of stoneware.13 In many ways, Johannes Ebbers and Tobias van Belle are illustrative for the bigger picture of coffee and tea use in eighteenth-century Antwerp and Aalst as it is revealed in Tables 16.1-16.4. Whereas chocolate never acquired the status of a widely consumed commodity,14 tea and coffee quickly conquered large consumer markets.15 This is confirmed by the rising number of new shop establishments of retailers specializing in the retailing of sugar, coffee and tea in Antwerp (Figure 16.1). Moreover, the geographical dispersion of teashops across urban space—increasingly spreading out from the wealthy central parts of town—mirrors the grocery’s growing popularity 4 among ever larger social strata.16 Hence, when the Brabantine Estates organized a new ‘hearth tax’ in 1747, they included a forfeit levy ‘pour la consumption du thé’, payable by all inhabitants aged seven years or above.17 Clearly, by that time the consumption of tea was already considered sufficiently widespread to be used as a common basis for taxation.18 During the second half of the Eighteenth Century the total level of tea imports stagnated, or even declined slowly, while the import and consumption of coffee rapidly gained in weight and importance.19 Figure 16.1. New mercers: chocolate-, tea- and coffeeshops in Antwerp (N and per cent) 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Total % Table 16.1 Percentage of inventories with references to sugar or sugar-related household goods (sugar boxes, sugar dishes, sugar spoons, and so on) Period Antwerp Aalst L M+ L M+ 1675 (n=64) 0 3 1680 (n=86) 5 8 1710 (n=76) 0 4 1730 (n=93) 24 27 1740 (n=64) 8 3 1780 (n=75) 38 71 1790 (n=68) 20 53 Note: L: probate inventories of ‘lower’ social groups M+: probate inventories of ‘middling’ and ‘upper’ social groups (see text) 5 Table 16. 2 Percentage of inventories with references to hot drinks or hot drinks utensils Period Tea Coffee Chocolate Antwerp Aalst Antwerp Aalst Antwerp Aalst L M+ L M+ L M+ L M+ L M+ L M+ 1675 (n=64) 0 0 0 0 0 0 1680 (n=86) 0 0 0 0 0 8 1710 (n=76) 0 4 0 2 0 4 1730 (n=93) 55 78 3 41 21 55 1740 (n=64) 67 67 8 28 0 17 1780 (n=75) 69 95 38 77 7 59 1790 (n=68) 80 93 60 90 0 10 Note: L: probate inventories of ‘lower’ social groups M+: probate inventories of ‘middling’ and ‘upper’ social groups (see text) The rise of a new domestic culture? With this rapid spread of tea consumption came the introduction of a specific, at times almost ritual, culture of tea drinking. From the 1730s onwards specialised tea tables appeared in Antwerp households, and were sometimes even to be found in several otherwise less luxuriously furnished homes. Presumably, at this time, displaying tea ware was laden with symbolic meanings of social and/or decorative value. Especially designed tea shelves could serve this purpose, but also the mantelpiece of the chimney was a preferred site for ‘conspicuous tea display’—in 1729 Antwerp, for instance, Joannes Steencuyl used the mantelpiece of his chimney for displaying six ‘fine’ tea cups and saucers.20 Such display of tea-related commodities was rarer in the provincial homes of Aalst’s inhabitants, in whose inventories only two references to tea tables were found (both in the 1740s). The occasional reference to tea trays and tea spoons, as well as to sugar scissors and tongs (in seven households), sugar trays (four households) and milk jugs (44 households), nevertheless indicates similar tendencies toward the conspicuous display of a refined tea ritual in Aalst. As was also the case in the Northern Netherlands, ‘tea drinking utensils’ largely outnumbered coffee cups and dishes.21 In 1780, when coffee had already gained considerable popularity, only a minority of households owned coffee cups and saucers, whereas tea cups were still widely dispersed. Moreover, while tea drinking gave birth to a refined material culture and a 6 variety of household goods (such as the aforementioned tea-trays, tea-tables, tea-spoons, etc.) coffee seems to have failed to enact a similar process during this same period. Yet, despite the supposedly marked ‘ritual’ character of tea drinking and the elaborate material and visual culture associated with it, the location of tea and coffee utensils in the houses of the deceased in Antwerp and Aalst suggests that drinking coffee and tea quickly became a matter of ‘daily routine’. Obviously, quite a lot of cups and saucers were inventoried in the kitchen, but all other rooms of the house could easily be considered appropriate venues for teapots or coffee cups as well. It is perhaps surprising that tea and coffee utensils were not particularly concentrated in the ‘front stage’ and representative rooms of the urban dwellings. Anthoine Hellin, for example, an Antwerp merchant occupying a rich urban dwelling on the ‘Meir’, one of the most prestigious streets of the city, owned two tea tables and several other tea-related utensils. However, they were not clustered in the front-stage rooms, but rather dispersed across the corridor, his office, and other rooms big or small, upstairs and downstairs.22 Maria Theresia Willemsens, on her part, kept tea cups and saucers in the backroom where she died on 5 May 1730, and even the tea table was inventoried in a (other) backroom on the first floor.23 Likewise, Jan Kennis’ tea ware in 1730 was dispersed across four front rooms and backrooms of the house.24 Compared to Antwerp, such patterns of dispersion set in decidedly later in the small town of Aalst: only from the 1740s does hot drinks apparel start to show up in upstairs chambers for instance. However, between the 1740s and the 1790s the share of tea- and coffee cups found in ‘front stage’ rooms declined from 49 per cent to 32 per cent, while the proportion of upstairs- or backrooms rooms containing cups rose from 11 per cent to 22 per cent. To a certain extent this spatial pattern has to be attributed to the development of more complex and nuanced patterns of domestic room use than simple front- and backstage dichotomies suggest—such as in the case of the ‘grand bedroom’ which combined both intimate and public functions.25 Nevertheless, the general pattern suggests that already by 1730 in Antwerp, and from mid-century in provincial Aalst, hot drinks culture was not only popularized, but clearly came to 7 belong to the realm of daily routine.26 Hence hot drinks seem to have lost their (intrinsic) novelty and potential for social and cultural distinction relatively quickly.27 Seen from this perspective, the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century advertisements and trade cards that explicitly linked tea and coffee to the exotic and faraway corners of the world from which they stemmed, appear more convincingly aimed at reminding consumers of the novelty, authenticity and exoticism which these goods had formerly commanded, rather than reflecting the meaning they still carried in their quotidian consumption.28 The intrinsic novelty and exoticism of tea and coffee thus seems to have been largely worn out by the middle of the Eighteenth Century, and were replaced by wider and varied repertoires of meaning related to physical comfort, pleasure and sociability. 8 Hot drinks and ‘material modernity’ Several scholars have argued that the expansion of hot drinks consumption stimulated the use and production of a wide variety of crockery throughout eighteenth-century Europe.29 Since glazed types of earthenware such as majolica, tin-glazed ceramics, or porcelain were better suited for coffee and tea than their metallic counterparts, it is not difficult to imagine how hot drinks could have contributed to a (more general) tendency towards a less durable material culture. In its turn, this transformation has been associated with deeper-seated changes in the mentalities of early modern consumers, who increasingly seemed to value aesthetics instead of durability and the intrinsic value of raw materials.30 Unfortunately, this phenomenon cannot be easily documented on the basis of the probate inventory database at our disposal. The inventories only rarely—and never consistently—label the precise material of which ceramic items were made. Therefore it remains hard to tell whether the relatively abundant porcelain mentioned in the Antwerp inventories (Table 16.3) was of a genuine Asian-made variety, or rather one of the cheaper European substitutes. After 1708 the distinction became even more muddied, when in Meissen and other places genuine European porcelain began to be produced. Compared to Antwerp, however, porcelain appears much less prevalent in the Aalst inventories; whereas (tin-)glazed earthenware was already very common there from the end of the Seventeenth Century. Regardless of their precise materiality or place of production, it is nevertheless clear that the hot drinks culture gave a strong impetus to the use of crockery in the eighteenthcentury household. 9 Table 16.3 Percentage of inventories with references to porcelain or glazed earthenware Period Antwerp Aalst Glazed earthenware & Glazed Porcelain Porcelain delftware earthenware L M+ L M+ L M+ L M+ 1675 (n=64) 0 0 42 35 1680 (n=86) 11 35 53 65 1710 (n=76) 0 10 71 51 1730 (n=93) 17 61 76 84 1740 (n=64) 0 33 42 42 1780 (n=75) 55 81 55 82 1790 (n=68) 0 20 70 85 Note: L: probate inventories of ‘lower’ social groups M+: probate inventories of ‘middling’ and ‘upper’ social groups (see text) At first sight this seems to confirm Shammas’ hypothesis about the impact hot drinks exerted upon the eighteenth-century material culture of the home at large. And indeed, hot drinks and the rituals surrounding the consumption of colonial groceries almost certainly contributed to the rapid spread in the number and variety of ceramics of different kinds, colours and decorative schemes. Nevertheless, a closer scrutiny of the inventory material suggests that the fundamental shift in the mental attitude towards breakable consumer goods had occurred centuries prior to the advent of hot drinks. In Aalst the first evidence of domestic tea and coffee consumption would only emerge from the beginning of the Eighteenth Century, even though the growing prevalence of glazed earthenware was already clearly apparent before that time. In Antwerp the first porcelain objects show up in inventories from the late Sixteenth Century onwards, while majolica was already well known by that time.31 By 1630 almost 50 per cent of all Antwerp’s inventoried households owned porcelain objects of different kinds: pots, dishes, saucers, butter dishes, ale pints, etc. The success of imported porcelain in the early Seventeenth Century occurred at the detriment of the home-made ‘majolica’ production. It is telling that while sixteenth-century majolica bakers often borrowed design motives from a ‘renaissance’ repertoire, by the early Seventeenth Century majolica bakers introduced exotic, Eastern motives in an effort to counter the competition of Asian porcelain 10 imports. Unsurprisingly, in the 1630 Antwerp sample, the newer porcelain was more often used for display in the representative rooms of the house, where it seems to have driven out the earlier home-made majolica luxuries. In comparison to the sixteenth-century tin-glazed earthenware, porcelain was indeed a far superior product category.32 By 1730 porcelain and delftware were rapidly gaining in importance on the Antwerp table. It nevertheless seems clear that not Asian imports but Italian majolica production had played the pivotal role in creating the necessary mental categories for ‘material modernity’ in the area of crockery. Majolica as well, after all, derived its value mainly from aesthetic qualities and design rather than from the intrinsic value of the raw materials used in its production. This is clearly indicated by the fact that majolica producers in Antwerp registered themselves as members of the guild of St.-Luke, and hence identified themselves as artists rather than as artisans. Without denying its importance altogether, these findings qualify the ‘transformative power’ of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Asian exchange in bringing about a new ‘consumer mentality’. On the contrary, late sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Asian porcelain imports did build upon mental categories of ceramics ownership and consumption that were already present in sixteenth-century Europe, even though at that time tableware items were still predominantly made from pewter and silver. The culture of hot drinks consumption will undoubtedly have contributed to the rising popularity of crockery in early modern households—but the mental way towards a breakable and more ‘modern’ consumer pattern had already been paved from at least the Sixteenth Century onwards. Domestic sociability and colonial groceries A similar reassessment can be made for the social, ritual and cultural analysis of the success of ‘hot drinks’ in the history of domestic sociability. Undoubtedly, chocolate, coffee and tea profoundly affected patterns of sociability and respectability.33 Their advent changed daily time-schedules and 11 influenced drinking and eating rituals throughout the Southern Netherlands.34 Yet it would be a mistake not to take the already existing and highly elaborated patterns of domestic sociability and refined table manners into consideration when accounting for the rapid spread of a hot drinks culture among all strata of society.35 The very presence—for example—of specialised dining rooms in some sixteenth- and (again) in late seventeenth-century probate inventories points in the direction of an already pre-existing, elaborate elite sociability.36 Yet, the general adoption towards a more elaborate dining culture was by no means confined to the upper strata of society. To take but one example: the rapid spread of the fork among lower layers of our Antwerp probate inventory group testifies to the development of a more generalized refined and ‘polite’ dining culture among all layers of society. Period 1675 (n=64) 1680 (n=86) 1710 (n=76) 1730 (n=93) 1740 (n=64) 1780 (n=75) 1790 (n=68) Note: Table 16.4 Percentage of inventories containing at least one fork Antwerp Aalst L M+ L M+ 0 5 11 40 0 28 41 89 8 19 45 66 30 63 L: probate inventories of ‘lower’ social groups M+: probate inventories of ‘middling’ and ‘upper’ social groups (see text) This gradual social diffusion of the fork in Antwerp and soon also in Aalst, parallel with those of for instance tablecloths and individual plates, is indicative of a long-term trend towards more refined, respectable or polite practices of domestic sociability. The increasing prevalence of the fork went hand in hand with—and was made possible by—their changing material form: fewer forks were now made of silver, and more frequently were they now in pewter or iron steel, which eventually made them subject to under-registration in the inventories by the end of the period under review. 12 The same tendency towards increasing politeness and refinement and a cheaper material culture which brought this within reach of growing social layers of society as has been described for the consumption of hot drinks, can thus be discerned in wider practices of domestic sociability already well before the introduction of these colonial groceries. Again, even though the hot drinks culture had an enormous appeal and impact upon Europeans in the Eighteenth Century, the mental categories for the success of the hot drinks culture were already established long before chocolate, tea and coffee were actually introduced. With regards to the material culture of tea drinking itself, John Styles has convincingly shown how silver teapots helped to make the tea culture ‘recognizable’ among well-to-do Londoners in the late Seventeenth Century.37 Our argument here suggests that this observation holds on a much wider level as well. European urban culture did not need coffee and tea to develop a ‘culture of respectability’.38 Rather, these new hot drinks were easily ‘fitted’ into the existing (and developing) cultural and behavioural codes of urban society, and owed much of their success precisely to their capacity for flexible appropriation within this existing social and cultural context. This brings us back to the consumer motivations underlying the rapid spread of the practices and ‘consumption bundles’ related to the drinking of caffeinated beverages.39 Far from fundamentally transforming European urban culture by introducing new attitudes to consumer behaviour such as a desire for the novel and exotic, a tendency towards elaborate domestic practices of food- and drink-related sociability, an appreciation of physical comfort and pleasure, and a cultivation of health and sobriety, it could be argued that tea and coffee primarily became sought after precisely because they readily lent themselves to appropriation within these already pre-existing cultural frameworks. The Ostend trade in tea and consumer behaviour If the qualitative aspects of the rapid adoption of hot drinks in the Southern Netherlands show more continuity than change, how then can we account for the fact that these—together with tobacco— 13 were rapidly to become truly mass-consumed commodities during the first half of the Eighteenth Century? Perhaps the brief but tumultuous adventures of the Southern Netherlands in the area of overseas trade can offer some clues. Coinciding with the period of the massive adoption of tea consumption during the first half of the Eighteenth Century, the Ostend Company briefly provided the region with its own direct source of Asian imports. From 1715 onwards, a number of rich merchant investors (mainly from Antwerp and Ghent) began sending trade expeditions to Chinese Canton. In 1722 mutual cooperation was ensured by the official establishment of the ‘General Indian Company’ (GIC) by Emperor Charles VI. It was better known as the ‘Ostend Company’ since its maritime activities were all centred on the port of Ostend, which was the region’s only direct North Sea port, and the only haven where trade free from duties remained possible after the closing of the Scheldt in 1585.40 Although it quickly met with resistance from the dominant players in the East-Asian trade, the GIC was nevertheless a remarkable commercial success for the time it lasted.41 Trade expeditions were directed to both India (Bengal and the Coromandel Coast) and China (Canton), but the vast majority of profits were realized in the latter trade. Moreover, the majority of imported value consisted of tea (56 per cent in total, between 1724 and 1732), trailed only at a wide distance by silk (35 per cent) and porcelain (8 per cent).42 Compared to the English and Dutch East India Companies, the GIC soon found its niche market in the import of cheap black Bohea tea. Of its total tea imports no less than 74 per cent consisted of the Bohea variety—compared to perhaps no more than approximately 45 per cent for both the English and the Dutch East India Companies.43 It is not clear whether this was a conscious strategy from those in charge at the GIC to abandon the traditional luxury markets and focus upon cheaper mass consumption, or a consequence of its rogue-like and somewhat marginal position as a newcomer to overseas trade. According to the company’s correspondence, the choice for black tea was mainly motivated by its easier preservation. Moreover, Chris Nierstrasz has suggested that the supply of black tea was more flexible than that of the green 14 teas—thus offering better opportunities for a newcomer. The choice for a cheap tea variety, such as the Bohea, meanwhile, seems at least partially informed by the inexperience of the (often British) supercargoes employed on these expeditions. Fraud in tea quality was common, and a concern for recognizing the correct tea types loomed large in the company’s correspondence. Louis Bernaert, the commissioner of the GIC in Ostend, remarked in 1728 that he was ‘somewhat apprehensive towards the fine teas, … since […] we do not have the appropriate knowledge of these goods.’44 This reliance on the market for cheap teas, which distinguished the Ostend Company from their more venerable competitors, did not inhibit its commercial success. Quickly, but briefly, the GIC conquered a significant share of the European market for tea. During its active years (1719-1728) roughly 42 per cent of total tea imports were brought to Europe by the Ostend Company.45 As soon as international political pressures against the activities of the GIC culminated in its suppression, the Dutch East India Company moved into this newly discovered consumer market for the cheap, black Bohea tea.46 In a way then, it seems that tea’s transition from a luxury to a mass-consumed staple good throughout Europe had some early roots in the Southern Netherlands. It is thus no surprise to learn that the price of tea was significantly lower in this region than in either the Dutch Republic or England during this period.47 In this respect, the widespread success of tea—and later coffee—in times of economic stress, along with the expansion of a material culture which favoured relatively cheap earthenware materials at the expensive of pewter, copper and silver, seems much less of a contradiction than it appears at first. Perhaps then, there is little reason to take resort to explanations involving profound cultural and social transformations, or even material revolutions, in order to explain the mass consumption of tea (and coffee) in the Eighteenth Century, when the success of these commodities seems attributable precisely to their affordability in times of economic hardship and status quo. 15 Conclusions There exists generally little disagreement among social, economic and cultural historians about the ‘transformative power’ of (sweetened) hot drinks on European society.48 This case study did nothing to qualify the long-term importance of these commodities. Indeed, very soon the inhabitants of Antwerp and Aalst of very different social groups all participated in this new culture. Though hot drinks were sometimes used for distinctive ‘display’ purposes and tea time and coffee houses contributed to ritualized refinement, for the majority of consumers drinking coffee and tea seems to have gained a routine status during the Eighteenth Century. This perhaps helps to explain why so little reference was made in the probate inventories to the Asian origin of these groceries in the material culture which accompanied their use. Indeed, lacquered tea tables were sold, and some people owned porcelain sets with Chinese or Japanese motives and drawings. Maria Van Alphen, an Antwerp spinster who died in 1778, for instance, owned several ‘Japanese’ porcelain items.49 Among them figured nine tea cups and saucers. Yet all in all, such references are very rare. Perhaps this corresponds to the early initiation of a process of cultural mediation in which European merchants and designers were providing the required decoration, design and product schemes to Asian producers according to European tastes. Indeed, as was the case with sugar, coffee and tea, porcelain was quickly and easily appropriated within European culture, without necessarily remaining attached to the exotic and global provenance of these goods. Contrary to the argument of Troy Bickham, we would therefore suggest that it were not these exotic groceries themselves that constituted the most dynamic factor in drawing European consumers into the wider world of empire.50 The thrusting force seems more reasonably to be found in the specific (urban) culture and society which emerged from the late medieval period onwards and which shaped Europe’s specific repertoires of consumer valuation. Far from constituting an external process which had to be rendered recognizable or familiar to European consumers and producers, the very introduction of exotic groceries (and the merchant empires and plantation 16 systems which these helped bring about) was largely inherent to the already pre-existing social and cultural structures and dynamics of the European alimentary fashion system. The diffusion of tea and coffee among broad layers of urban society in the Southern Netherlands occurred first in Antwerp, but spread with only little delay towards Ghent and secondary towns such as Aalst, but also Lier, Lokeren and, later still to such small towns as Eeklo and Roeselare.51 In terms of the domestic consumption of hot drinks, rural households clearly lagged behind, and would only begin to catch up during the second half of the Eighteenth Century.52 When comparing the spread of material culture related to the consumption of exotic groceries in the Southern Netherlands to similar evidence for the Dutch Republic and England, it is striking how closely the consumption of hot drinks in the Southern Netherlands trailed that of its more economically dynamic and commercial neighbours.53 Hierarchies of consumption appear to have been predominantly shaped by the dividing lines between rural and urban societies, rather than between commercially expanding economies and those suffering from stagnation and deindustrialization. It seems then, that the spectacular popularity of colonial groceries ties in better with certain pre-existing features of early modern urban culture and society rather than with any processes of imperialism or economic growth which might have uniquely characterized either England or the Dutch Republic. Tendencies towards the further elaboration of domestic forms of polite and refined sociability, for instance, were evident in wider areas of material culture unrelated to the consumption of hot drinks. Likewise, even though the shift from a more expensive material culture based on intrinsic value towards a growing preference for cheaper and less durable consumer goods such as crockery was certainly accelerated by the widespread consumption of hot drinks, it was part and parcel of a process which had both deeper and earlier roots in the repertoires of consumer valuation of early modern Europe.54 Embedding the individual consumption of hot drinks in such wider social and cultural patterns does not preclude the existence of many different, often 17 overlapping and individual forms of consumer motivation. Nevertheless, even the aspects of individual consumer motivation most obviously related to the ‘intrinsic’ and ‘natural’ properties of these exotic groceries, such as a desire for physical comfort, health and sobriety, can probably be aligned with social and cultural processes which were already well under way before the first inhabitants of Aalst or Antwerp could experience the taste of tea, coffee, chocolate or tobacco.55 Seen in this perspective, the impact of hot drinks consumption upon transforming European material cultures was more of a quantitative rather than a qualitative nature. Without denying the fundamental importance of the new cluster of consumer behaviour which formed around the consumption of exotic hot drinks, a closer examination of the materiality, location and use of these consumer goods as recorded in the probate inventories, nevertheless leads us to suggest that the mental categories which accompanied them were already deeply rooted in the pre-existing social, cultural and behavioural codes of European urban society. 1 See for a recent overview Jan De Vries, The industrious revolution: consumer behavior and the household economy, 1650 to the present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), pp. 154-58; R. Van Uytven, Geschiedenis van de dorst. Twintig eeuwen drinken in de Lage Landen (Leuven: Davidsfonds Uitgeverij, 2007), pp. 127-47; C. Vandenbroeke, Agriculture et alimentation (Gent: Belgisch centrum voor landelijke geschiedenis, 1975), pp. 566-78, J.J. Voskuil, 'Die Verbreitung Von Kaffee Und Tee in Den Niederlanden', in N.-A. Bringéus (ed.), Wandel Der Volkskultur in Europa (Münster: Coppenrath, 1988). 2 Woodruff D. Smith, 'From coffeehouse to parlour. The consumption of coffee, tea and sugar in North-Western Europe in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries', in J. Goodman, P.E Lovejoy and A. Sherratt (eds), Consuming habits. Global and historical perspectives on how cultures define drugs (London: Routledge, 1995), p. 187. 3 B. Blondé, 'Toe-eigening en de taal der dingen. Vraag- en uitroeptekens bij een stimulerend cultuurhistorisch concept in het onderzoek naar de materiële cultuur', Volkskunde, 104 (2003); W. Ryckbosch, 'A consumer revolution under strain? Consumption, wealth and status in eighteenth-century Aalst (Southern Netherlands)' (PhD dissertation, University of Antwerp & Ghent University, 2012), pp. 252-57. 4 S. Mintz, Sweetness and power: the place of sugar in modern history (New York: Penguin Books, 1986), p. 267. 5 Jan De Vries, 'Between purchasing power and the world of goods: understanding the household economy in early modern Europe', in J. Brewer and R. Porter (eds), Consumption and the world of goods (London: Routledge, 1993); Jan De Vries, 'The industrious revolution and economic growth, 1650-1830', in P.A. Davis and M. Thomas (eds), The economic future in historical perspective (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003); De Vries, The industrious revolution. See also Anton Schuurman, 'Aards geluk. Consumptie en de moderne samenleving', in Anton Schuurman (ed.), Aards geluk. De Nederlanders en hun spullen van 1550 tot 1850 (Amsterdam: Balans, 1997), pp. 22-25. 18 6 Anne McCants, 'Exotic goods, popular consumption, and the standard of living: thinking about globalization in the Early Modern world', Journal of World History, 18 (2008), p. 173. 7 Carole Shammas, The preindustrial consumer in England and America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990). 8 Jon Stobart, Sugar and spice. Grocers and groceries in Provincial England, 1650-1830 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012). 9 De Vries, The industrious revolution, pp. 44-45. 10 J. Parmentier, Oostende & Co: het verhaal van de Zuid-Nederlandse Oost-Indiëvaart, 1715-1735 (Gent: Ludion, 2002); J. Parmentier, Tea time in Flanders. The maritime trade between the Southern Netherlands and China in the 18th Century (Gent, 1996). 11 Anton Schuurman and Paul Servais (eds), Inventaires après décès et ventes de meubles. Apports à une histoire de la vie économique et quotidienne (XIVe-XIXe siècle). Actes du séminaire tenu dans le cadre du 9ième Congrès International d'Histoire économique de Berne (1986) (Louvain-la-Neuve: Academia, 1988), pp. 131-51. 12 MA Antwerp, Notarial Protocols (P.J. Van Dijck, 1779), nr. 4005. 13 MA Aalst, Oud Archief, Staten van Goed, n° 1910 (Josina Hoebacke, †1791). 14 M. Libert, 'De chocoladeconsumptie in de Oostenrijkse Nederlanden', in Bruno Bernard, Jean-Claude Bologne, and William G. Clarence-Smith (eds), Chocolade: van drank voor edelman tot reep voor alleman, 16de - 20ste eeuw (Brussel: ASLK, 1996), pp. 77-80. 15 Lorna Weatherill, Consumer behaviour and material culture in Britain 1660-1760 (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1988), p. 177; Thera Wijsenbeek-Olthuis, Achter de gevels van Delft. Bezit en bestaan van rijk en arm in een periode van achteruitgang (1700-1800) (Hilversum: Verloren, 1987), p. 229. 16 Laura Van Aert and Ilja Van Damme, 'Retail dynamics of a city in crisis: the mercer guild in pre-industrial Antwerp (c.1648-c.1748)', in Bruno Blondé and Natacha Coquery (eds), Retailers and consumer changes in Early Modern Europe. England, France, Italy and the Low Countries (Tours: Presses Universitaires François-Rabelais, 2005), p. 161. 17 Only the supported poor were officially exempted from the ‘tea tax’. See the August 28, 1747 ordnance in Louis Prosper Gachard, ed., Recueil des ordonnances des Pays-Bas autrichiens. Troisième série (1700-1795). Vol. 6 (Brussels: Goemaere, 1860-1885). 18 Anne McCants, 'Poor Consumers as Global Consumers: the Diffusion of Tea and Coffee Drinking in the Eighteenth Century', The Economic History Review, 61 (2008), pp. 196-98. 19 Vandenbroeke, Agriculture et alimentation, p. 570. 20 MAA, Not., Prot. 1717. 21 Compare Hester Dibbits, Vertrouwd bezit. Materiële cultuur in Doesburg en Maassluis, 1650-1800 (Nijmegen: SUN, 2001), p. 159. 22 MAA, Not., Prot. 1556. 23 MAA, Not., Prot. 3265. 24 MAA, Not., Prot. 2306. 25 Amanda Vickery, 'An Englishman's home is his castle? Thresholds, boundaries and privacies in the eighteenthcentury London house', Past and Present, 199 (2008). 26 McCants, 'Poor consumers as global consumers', p. 191. 27 Voskuil, Die Verbreitung, p. 419. 28 Stobart, Sugar and spice. 29 Bruno Blondé, 'Cities in decline and the dawn of a consumer society. Antwerp in the 17th-18th centuries', in Bruno Blondé, et al. (eds), Retailer and consumer changes in Early Modern Europe. England, France, Italy and the Low Countries. Marchands et consommateurs: les mutations de l’Europe moderne. Angleterre, France, Italie, Pays-Bas. Actes de la session “Retailers and consumer changes”. 7ième conference inetrantionale d’histoire urbaine “European City in Comparative Perspective”. Athènes - le Pirée, 27-30 octobre 2004.(Tours, 2005); Bruno Blondé, 'Tableware and changing consumer patterns. Dynamics of material culture in Antwerp, 17th-18th centuries', in Johan Veeckman (ed.), Majolica and Glass from Italy to Antwerp and beyond. The Transfer of Technology in the 16th-early 17th century (Antwerp, 2002); Harm Nijboer, De fatsoenering van het bestaan. Consumptie in Leeuwarden tijdens de Gouden Eeuw. (Groningen, 2007); Harm Nijboer, 'Fashion and the early modern consumer evolution. A theoretical exploration and some evidence from seventeenth-century Leeuwaarden.', in Bruno Blondé, et al. (eds), Retailers and consumer changes in Early Modern Europe. England, France, Italy and the LowCountries (Tours: Presses universitaires François-Rabelais, 2005); Carole Shammas, The Pre-Industrial Consumer in 19 England and America. (Oxford: Clarendon, 1990); Lorna Weatherill, The growth of the pottery industry in England 1660-1815 (New York: Garland, 1986), p. 102. 30 Bert De Munck, 'Products as gifts and skills as hybrids: opening a black box in the history of material culture', Past and Present (forthcoming). 31 Carolien De Staelen, 'Spulletjes en hun betekenis in een commerciële metropool. Antwerpenaren en hun materiële cultuur in de zestiende eeuw' (PhD Thesis, University of Antwerp, 2007). 32 C. Dumortier, Céramique de la Renaissance à Anvers. De Venise à Delft (Brussels: Racine, 2002); C. Dumortier, 'Italian influence on Antwerp majolica in the 16th and 17th century', in The Ceramics cultural heritage (Florence, 1995). 33 Brian Cowan, The social life of coffee. The emergence of the British coffeehouse (London: Yale University Press, 2005); Woodruff D. Smith, Consumption and the making of respectability (London: Routledge, 2002). 34 Blondé, Toe-eigening. 35 Dibbits, Vertrouwd bezit, p. 160; R. Jansen-Sieben, 'Europa aan tafel in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden (15de eeuwca.1650): een inleidend overzicht' and C. Terryn, 'Eenvoud en delicatesse: norm en realiteit van de tafelmanieren in het 18de-eeuwse Gent', both in F. De Nave and C. Depauw (eds), Europa aan tafel. Een verkenning van onze eet- en tafelcultuur (Deurne: MIM, 1993). 36 Compare with the eighteenth-century ‘age of the dining table’ in Stana Nenadic, 'Middle-rank consumers and domestic culture in Edinburgh and Glasgow 1720-1840', Past and Present, 145 (1994), p. 146. 37 J. Styles, 'Product Innovation in Early Modern London', Past and Present, 168 (2000). 38 Compare with Smith, Consumption and the making of respectability. 39 De Vries, The industrious revolution, pp. 31-37. 40 Parmentier, Oostende & Co, p. 15. 41 Karel Degryse has estimated the net returns of the GIC at 149,3 percent furing the 1722-1735 period: Karel Degryse, De Antwerpse fortuinen: kapitaalsaccumulatie, -inverstering en -rendement te Antwerpen in de 18de eeuw (Antwerpen Universiteit Antwerpen, 2005), pp. 537-8. 42 K. Degryse, 'De Oostendse Chinahandel (1718-1735)', Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Filologie en Geschiedenis, 52 (1974), p. 315. 43 See the contribution by Chris Nierstrasz to the current volume. 44 Letter from Bernaert to de Pret, 24 april 1728, cited in Degryse, De Oostendse Chinahandel (1718-1735), pp. 31619. 45 Degryse, De Oostendse Chinahandel (1718-1735), p. 329. 46 See Chris Nierstrasz in this volume. 47 Degryse, De Oostendse Chinahandel (1718-1735), pp. 330-31. 48 McCants, Poor consumers as global consumers, p. 173. 49 MAA, Not., Prot. 716. 50 T. Bickham, 'Eating the empire: intersections of food, cookery and imperialism in eighteenth-century Britain', Past and Present, 198 (2008); Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Tastes of paradise: a social history of spices, stimulants, and intoxicants (London: Vintage, 1993). 51 B. Depla, 'De consumptierevolutie in de nieuwe tijd. Casus: de stad Roeselare en de omringende plattelandsdorpen in de 18de eeuw' (Ma Thesis, Ghent University, 2005); S. Kuypers, 'Materiële cultuur in Lokeren, Eksaarde en Daknam in de 17de en 18de eeuw' (Ma Thesis, Ghent University, 2006); Johan Poukens and Nele Provoost, 'Respectability, middle-class material culture, and economic crisis: the case of Lier in Brabant, 16901770', Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 42 (2011); Ryckbosch, A consumer revolution. 52 I. Crombé, 'Studie van 18de-eeuwse plattelandsinterieurs te Evergem' (Ma Thesis, Ghent University, 1988); I. Jonckheere, 'Boer zkt comfort. Studie van het consumptiegedrag in relatie tot de levenscyclus in het Land van Wijnendale in de 18de eeuw' (Ma Thesis, Ghent University, 2005); C. Schelstraete, H. Kintaert, and D. De Ruyck, Het einde van de onveranderlijkheid. Arbeid, bezit en woonomstandigheden in het Land van Nevele tijdens de 17e en de 18e eeuw (Nevele, 1986); L. Van Nevel, 'Materiële cultuur op het platteland tijdens de 18de eeuw' (Ma Thesis, Ghent University, 2005). 53 Johan A. Kamermans, Materiële cultuur in de Krimpenerwaard in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw, A.A.G. Bijdragen (Wageningen: Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen, 1999); Ken Sneath, 'Consumption, wealth, indebtedness and social structure in early modern England' (Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cambridge, 2009); Hans Van Koolbergen, 'De materiële cultuur van Weesp en Weesperkarspel in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw', in 20 A.J. Schuurman, J. De Vries, and A. Van Der Woude (eds), Aards Geluk. De Nederlanders en hun Spullen van 1550 tot 1850 (Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Balans, 1997). 54 Bert De Munck, 'The agency of branding and the location of value. Hallmarks and monograms in early modern tableware industries', Business History, 54 (2012). 55 John E. Crowley, The Invention of Comfort (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001); Patrick Wallis, 'Exotic drugs and English medicine: England's drug trade, c. 1550-c. 1800', Social History of Medicine, 25 (2012). 21