Difficulty Swallowing

advertisement

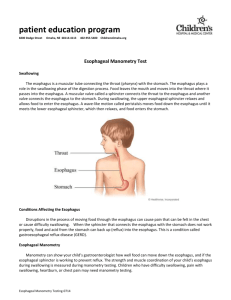

Difficulty Swallowing By gi health Swallowing is just another example of how we don't appreciate our bodies until something goes wrong. Normally, swallowing is a rapid and efficient action that requires less than two seconds to complete and one that all of us take for granted. After all, we have been doing it since birth and never had reason to give it a thought. We just expect our food to naturally find its way to our stomach without falling into our lungs and cutting off our breathing. Actually the process is quite complicated requiring coordination of a large number of muscles in the mouth, throat, and esophagus, but usually all goes well and it can be taken for granted. It's Stuck What a surprise it is then when an individual is sitting in a nice restaurant, perhaps in the middle of a romantic meal or an important business luncheon, and suddenly a piece of meat becomes lodged in their esophagus. It went down okay - but not all the way. It just hangs there, right in the middle. It won't go down, nor can it be brought back up. Anxiety develops as a sensation of pressure occurs in the chest and foamy saliva begins to back up. Breathing is not impaired since there are two "pipes" - the foodpipe (esophagus) and the windpipe (trachea) - and the latter is not affected. But, what a miserable, embarrassing, and helpless feeling. Sometimes the blockage will resolve on its own with a great sense of relief. But, usually after more than several hours of procrastination, these individuals seek medical attention. You can find them several nights a week sitting in the ER with a paper cup in hand to catch their saliva. This common problem is usually not resolved until an emergency procedure is performed to remove the offending object. Relief is instant. The next step is to find out why this has happened and how to prevent it from happening again. What Tests are Needed? Diagnosis is an important first step in treatment. Before the doctor can develop a treatment plan, tests must be performed to determine what caused the problem. Testing will usually begin with a medical history and physical exam. The doctor will want to know how often and under what circumstances the problem occurs. Most cases will require a "scope" test of the upper digestive system. Also known as a gastroscopy or EGD exam, this simple test is quickly and painlessly performed using a mild sedative. A thin, flexible, sterilized tube is passed through the mouth and down into the esophagus and stomach. A tiny color video camera within this instrument allows the doctor to directly examine the esophagus, stomach, and upper small intestine. When necessary, photographs and biopsies can be obtained for later review. Occasionally, barium x-rays may be requested to view the esophagus while swallowing. Less commonly, the doctor may request an esophageal manometry study which measures the strength and coordination of the esophageal contractions as well as the pressure of the special "trapdoor valve" between the stomach and esophagus. By performing these tests the doctor can most accurately determine exactly what is causing difficulty swallowing and what treatment will be necessary. Strictures and Rings Most patients have trouble swallowing because their lower esophagus has become damaged from the corrosive effects of chronic acid heartburn. This eventually leads to the build-up of scar tissue and then a narrowing, or stricture, of the esophagus. Some patients have similar symptoms due to the formation of a peculiar ring of scar tissue in the lower esophagus. The cause of this so-called Schatzki's ring is not known. Both strictures and rings act like roadblocks preventing the passage of food down into the stomach. These strictures and rings are often associated with a hiatal hernia - a minor displacement of part of the stomach through the diaphram and up into the chest. A hiatal hernia is a common condition and does not cause difficulty swallowing by itself. But when associated with a stricture or ring, symptoms may occur. To prevent further swallowing problems, this roadblock must be opened using a technique called esophageal dilatation which stretches the narrowed spot. A variety of devices are available to help your doctor open up the passageway. These include simple dilators, or bougies, that are flexible tapered rubber tubes that come in various diameters. Several bougies of increasing size may be passed down the esophagus in one session to dilate the stricture. This can be done with or without sedation. Most often, dilatation of a benign stricture or ring can be accomplished at the same time as the gastroscopy scope exam. Once the stricture is identified, a thin deflated balloon dilator can be passed through the scope and positioned across the narrowed segment. This cigar-shaped balloon is then inflated with water and held in place for several minutes. This repairs the stricture in much the same way as an angioplasty corrects a blocked artery in the heart. The balloon dilator is then removed and the scope withdrawn. However, if at the time of the scope examination, the esophagus is very inflamed or ulcerated, the dilatation may have to be delayed until the ulcers are healed. What Are The Risks? In most cases, dilatation of an esophageal stricture or ring is performed without problems. However, in rare cases complications can occur. The most common complication is bleeding. There is usually some minor bleeding with successful dilatation, but not enough to cause problems or symptoms. Rarely, the bleeding may be persistent and require treatment. The most serious complication is perforation of the esophagus. The wall of the esophagus is thin and, despite your doctor's best efforts, a tear may occur during the dilatation. An operation is usually required to correct this problem. Fortunately, this is quite uncommon. What Else Could be Done? Another choice is to do nothing and to just live with the stricture, limit your diet to soft foods forever, and take your chances on having future choking spells. This is seldom advised. On the other end of the spectrum, you could have open chest surgery to remove the narrowed spot in your esophagus. This major surgery is usually reserved for only the most severe cases. For most patients, dilatation seems to be a more reasonable "middle ground." Will the Problem Return? It's hard to predict, but a large percentage of esophageal strictures eventually return as the scar tissue gradually shrinks tighter and tighter. Many patients undergo periodic esophageal dilatation to prevent further symptoms. The risk of recurrence can be reduced by preventing acid reflux and aggressively treating any symptoms of heartburn. Most people do best if they take prescription strength acid-reducing medications on a daily basis and pay attention to chewing properly. Cancer is Less Common A small number of patients have difficulty swallowing because of a tumor, sometimes cancerous, blocking the opening of their esophagus. This condition is obviously very important and requires prompt evaluation and treatment. A combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy is usually prescribed. Most cancers of the esophagus arise in abnormal cells that develop in response to chronic poorly controlled heartburn. Better control of the heartburn may prevent the cancer. If you have chronic heartburn, see your doctor before cancer has a chance to develop. Spastic Esophagus Sometimes there is no blockage that can be treated with dilatation. The problem may simply be a " disorganized," spastic, or weakened esophagus. This condition often affects the elderly. In this instance, instructions may be given to modify the consistency of the food, eat smaller and more frequent meals, use proper posture at the dinner table, take smaller bites, chew more carefully, and to consume plenty of fluids at mealtime. Better fitting dentures sometimes solves the problem. Neurological Problems Sometimes the problem is not digestive, but rather a neurological one, like a stroke or ministroke. About 30% of stroke patients will have dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing due to damage to the part of the brain that controls swallowing. Here there is no narrowed segment to dilate. Treatment is geared to support nutrition and other body functions until swallowing ability returns. A special feeding tube called a PEG is often inserted.