Rothschild - CLAS Users

advertisement

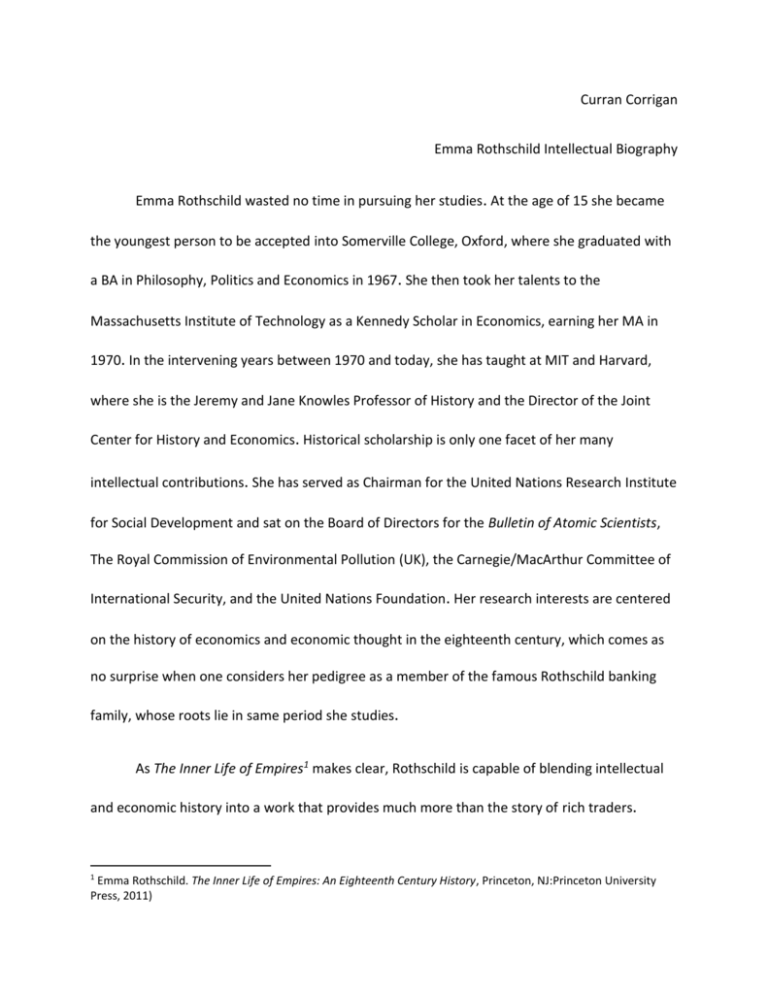

Curran Corrigan Emma Rothschild Intellectual Biography Emma Rothschild wasted no time in pursuing her studies. At the age of 15 she became the youngest person to be accepted into Somerville College, Oxford, where she graduated with a BA in Philosophy, Politics and Economics in 1967. She then took her talents to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as a Kennedy Scholar in Economics, earning her MA in 1970. In the intervening years between 1970 and today, she has taught at MIT and Harvard, where she is the Jeremy and Jane Knowles Professor of History and the Director of the Joint Center for History and Economics. Historical scholarship is only one facet of her many intellectual contributions. She has served as Chairman for the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development and sat on the Board of Directors for the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, The Royal Commission of Environmental Pollution (UK), the Carnegie/MacArthur Committee of International Security, and the United Nations Foundation. Her research interests are centered on the history of economics and economic thought in the eighteenth century, which comes as no surprise when one considers her pedigree as a member of the famous Rothschild banking family, whose roots lie in same period she studies. As The Inner Life of Empires1 makes clear, Rothschild is capable of blending intellectual and economic history into a work that provides much more than the story of rich traders. 1 Emma Rothschild. The Inner Life of Empires: An Eighteenth Century History, Princeton, NJ:Princeton University Press, 2011) Rothschild uses the Johnstones as a guiding example for the engagement of eighteenth century networks that proved crucial to the development of the British Empire. She examines the avenues of power which were available to men like the Johnstones, who could basically choose between achieve military service, overseas commerce, or marriage in pursuit of financial and social ascendancy. Rothschild was fortunate that the Johnstones were also connected to one of the most prominent issues in Atlantic history: the slave trade. By including Bellinda and Joseph Knight, Rothschild is able to transcend a narrow focus on elites. Indeed, the purpose of her book is to show the way that the imperial activities of Britain in the eighteenth century penetrated deep into the lives of even those who lived in the Scottish countryside . In doing so, she joins a growing movement of imperial historians who have discarded an approach based on “center/periphery” relationships in favor of using a much more dynamic and complex web of connections to define the experiences of imperial subjects. Her previous book, Economic Sentiments: Adam Smith, Condorcet and the Enlightenment,2 which used a comparative approach of prominent Enlightenment thinkers to examine the environment in which their early ideas were developed, received wide acclaim and has been published in four languages. Its greatest achievement is in dispensing with twentieth century conceptions of economics in her depiction of Adam Smith, arguing convincingly that Smith’s ideas were oversimplified in order to forward the conservative political agenda of William Pitt. Like Inner Life of Empires, Economic Sentiments demonstrates Rothschild’s ability 2 Emma Rothschild, Economic Sentiments: Adam Smith, Condorcet and the Enlightenment, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001). to draw useful connections as a way weaving a broader historical tapestry in which the sum is greater than the individual parts. While Inner Life of Empires spans the Atlantic World, it also serves as an important reminder of the existence of connections that involved much broader networks . Other contributions have been much more explicitly Atlantic in focus, such as her 2006 article “A Horrible Tragedy in the French Atlantic,”3 which examines the disastrous 1763 expedition to French Guyana led by Etienne-Francois Turgot. Rothschild traces the ramifications of this failed venture from Rochefort to Barbados, relying on primarily on intellectual correspondences. She has also recently contributed the chapter “Late Atlantic History”4 to the Oxford Handbook of Atlantic History edited by Nicolas Canny and Phillip Morgan. One unusual aspect of Rothschild’s studies is that she is explicitly concerned with engaging eighteenth century political economy in order to put us “in a position to understand their importance for the present.”5 This reflects the other side of Rothschild’s published work, which has included such diverse topics as the decline of the American automobile industry, environmental sustainability, and the definition of security. Rothschild’s division of labor between history and current events undoubtedly widens her methodological arsenal, but is lamentable in that she has only published three historical monographs over the course of her long career. However, it would seem that finishing her work with the Johnstones has provided 3 Emma Rothschild, “A Horrible Tragedy on the French Atlantic” Past and Present, Vol. 192 (August 2006), pp. 67-108. 4 Emma Rothschild, “Late Atlantic History” in Oxford Handbook to Atlantic History ed. Nicolas Canny and Phillip Morgan (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011). 5 Rothschild, Economic Sentiments, 47. scholarly invigoration. Her next work, Commerce and Anxiety in Eighteenth-Century France is estimated to begin publication sometime this year. The title suggests that it will follow the same thematic trends as her earlier studies, engaging economics and the intellectual currents which surrounded trade and material gain in order to provide compelling insights into eighteenth century society. Articles and chapters in books History “Late-Atlantic History,” The Oxford Handbook of Atlantic History, ed. Nicholas Canny and Philip Morgan, forthcoming 2011 “The Inner Life of Empires,” Tanner Lectures delivered at Princeton University, April 2006, forthcoming Tanner Lectures on Human Values, 2011 “Political Economy,” The Cambridge History of Nineteenth-Century Political Thought, forthcoming 2011 “Adam Smith in the British Empire,” Empire and Modern Political Thought, ed. Sankar Muthu, Cambridge, forthcoming 2011 “The Theory of Moral Sentiments and the Inner Life,” The Adam Smith Review, forthcoming 2010 “Choiseul and the History of France,” Waddesdon Miscellanea, vol. 1 (2009), pp. 6-13 “The Atlantic Worlds of David Hume”, Soundings in Atlantic History: Latent Structures and Intellectual Currents, 1500–1830, ed. Bernard Bailyn and Patricia Denault, Cambridge, MA, 2009, pp. 405-449 “The Archives of Universal History,” Journal of World History, Vol. 19, No. 3 (September 2008), pp. 375-401 “David Hume and the Seagods of the Atlantic,” The Atlantic Enlightenment, ed. Susan Manning and Francis D. Cogliano, Aldershot, 2008, pp. 81-96 “Adam Smith’s Laws,” Y a-t-il des lois en économie?, ed. Bernard Delmas, Villeneuve d’Ascq, 2007, pp. 37-40 “A Horrible Tragedy in the French Atlantic,” Past and Present, Vol. 192 (August 2006), pp. 67-108 “Adam Smith's Economics” (with Amartya Sen), The Cambridge Companion to Adam Smith, ed. Knud Haakonsen, Cambridge, 2006, pp. 319-365 “Arcs of Ideas: International History and Intellectual History,” in Transnationale Geschichte: Themen, Tendenzen und Theorien, ed Gunilla Budde, Sebastian Conrad and Oliver Janz, Göttingen, 2006, pp. 217-226 “'Axiom, theorem, corollary &c. ': Condorcet and mathematical economics,” Social Choice and Welfare, Vol. 25 (2005), pp. 287-302 “Language and Empire, c. 1800,” Historical Research, Vol. 78, No. 200 (May 2005), pp. 208-229 “Dibattito su Sentimenti economici,” Rivista di Storia Economica, Vol. 20, No. 2 (August 2004), pp. 243-252; symposium on Economic Sentiments “Dignity or Meanness,” The Adam Smith Review, Vol. 1 (2004), pp. 150-164; symposium on Economic Sentiments “Global Commerce and the Question of Sovereignty in the 18th Century Provinces,” Modern Intellectual History, Vol. 1, No. 1 (April 2004), pp. 325 “The English Kopf,” The Political Economy of British Historical Experience, 1688-1914, ed. D. Winch and P. O’Brien, Oxford, 2002, pp. 31-60 “La mondialisation en perspective historique,” Qu’est-ce que la culture?, ed. Y. Michaud, Paris, 2001, pp. 57-68 “An Alarming Commercial Crisis in 18th Century Angoulême: Sentiments in Economic History,” Economic History Review, 1998, Vol. 51, pp. 268-293 “Condorcet and Adam Smith on Education and Instruction,” Philosophers on Education, ed. A.O. Rorty, London, 1998, pp. 209-226 “Bruno Hildebrands Kritik an Adam Smith,” Bruno Hildebrands 'Die NationalÖkonomie der Gegenwart und Zukunft', ed. Bertram Schefold, Frankfurt, 1998, pp. 133-172 “Condorcet and the Conflict of Values,” Historical Journal, 1996, Vol 39, pp. 677- “Social Security and Laissez Faire in 18th Century Political Economy,” Population 701 and Development Review, December 1995, Vol. 21, pp. 711-744 “Adam Smith and the Invisible Hand,” American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, May 1994, pp. 319-322 “Psychological Modernity in Historical Perspective,” Essays in Honor of Albert Hirschman, Washington, DC, 1994, pp. 99-117 “Commerce and the State: Turgot, Condorcet and Smith,” Economic Journal, 1992, Vol. 102, pp. 1197-1210 “Adam Smith and Conservative Economics,” Economic History Review, 1992, Vol. 45, pp. 74-96