Application of hard carbon synthesized from leaves and cardboard

advertisement

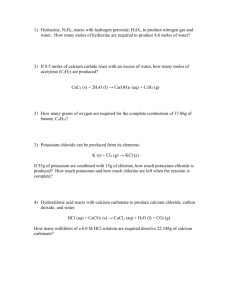

Application of hard carbon synthesized from leaves and cardboard for the cathodes of potassium-air batteries Shuo Liu Upper Arlington High School February, 2015 Application of hard carbon synthesized from leaves and cardboard for the anodes of potassium-air batteries Shuo Liu, 2817 Welsford Road, Upper Arlington, Ohio 43221 Upper Arlington High School, Upper Arlington, Ohio 43221 Mentor: Yiying Wu The reliability and efficiency of energy and energy storage is becoming ever more important as supplies of fossil fuel dwindle. Alternative sources of energy and new battery technologies have become focal points of major research. The purpose of this study was to determine if hard carbon could be successfully synthesized from different carbon sources, specifically leaves and cardboard, and then utilized in the cathode of a potassium air battery. A hard carbon powder was synthesized through pyrolysis and then mixed into a viscous slurry and applied to the anode. The battery coin cell was tested and results showed a high level of function. The voltage was consistent with other potassium air batteries and also exhibited stable long term charging and discharging. This could lead to further improvements in efficiency of the potassium-air battery and opens up the possibility of even using organic or waste materials to do so. This study has important implications for the future of battery technology and energy storage. Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank Mrs. Laura Brennan, the Science Research coordinator at Upper Arlington High School for making this all possible and helping me through my research project. I would also like to thank my mentor, Dr. Yiying Wu, a professor of chemistry at Ohio State University who allowed me to conduct research in his labs and guided me through my project. My thanks also goes out to Ren Xiaodi who supervised me and helped me out with my experiments in the lab. Last but not least, I would like to thank my parents for supporting and encouraging me all the way through my project. Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………....5 Materials and Methods………...……………………………………………....………….6 Results……………………………………………………………………..………………..8 Discussion and Conclusion…………………………………………………………..……9 References………………………………………………………..………………….……..11 Appendices……………………………………………………..……………………..…….12 Introduction The basic theory behind a battery is storing up chemical energy which can then be converted into electrical energy for use. The reaction that occurs is a flow of ions through the cell and out, and thus a flow of electrons, which provides the electrical energy. There are also usually electrolytes within the cell that help facilitate the movement of electrons and ions. Battery efficiency mainly depends on how well ions can flow within the battery and how restorable the anode and cathode materials are, which allows the battery to maintain longevity. As the world’s energy needs constantly ramp up, the need for efficient energy is also made ever more apparent. Currently, lithium ion batteries are an effective way to power important items, such as phones, laptops, or parts of electric vehicles. Hard carbon anodes have been incorporated into cells since they increase the irreversibility of the cell. The lithium ions fit into stacked graphene sheets which preserves the anode material for longer use (Buiel and Dahn, 1998). My approach was to use the hard carbon anode concept and apply it to potassium air batteries that the group I am working with is developing. The concept of the battery is that the cathode is a porous carbon material which is permeable to oxygen, such that the oxygen is able to diffuse through the cell to the potassium at the anode and oxidize it. The electrolyte solution is specifically KPF6, which is also permeable to oxygen (Ren and Wu, 2013). The problem with the current set up is that the oxygen comes into contact with the potassium too much, and forms a layer of potassium oxide above the anode. This reduces conductivity of the cell and causes the cell to lose efficiency. The problem with a direct application of the same graphene sheets is that potassium ions are much larger, meaning that they won’t be able to fit. Thus, we had to synthesize hard carbon, which has a different molecular structure comprised of hopefully vacuous spaces for the larger potassium ions to fit into (Ponrouch, Goni and Palacin, 2013). This paper details the synthesis and application of hard carbon to potassium cells and compares their performances to control cells. Materials and Methods Hard Carbon Synthesis Two dried oak leaves and a sheet of cardboard were collected. They first cut into smaller pieces, about 0.5 cm by 0.5 cm squares and then underwent a retting process. They were cleaned in separate beakers with 400 mL of deionized water. They were boiled off on hot plates at 100 degrees Celsius and with a stir bar at 400 rpm. They were heated until five minutes after they started to boil. The beakers were drained and the pieces of cardboard and leaves were collected with filter paper then dried off in a convection oven overnight. Afterwards, the dried leaves and cardboard were then separately pyrolysed in the tube furnace at 700 degrees Celsius for two hours under a nitrogen atmosphere. The calcinated carbon was then massed and ground using mortar and pestle into hard carbon powder. Cell Construction A viscous slurry was created by mixing the hard carbon powder with Super P, a commercial conductive carbon black, PVDF, a commercial thermoplastic fluoropolymer, and NMP, an organic solvent. The slurry was mixed in a 85% ratio hard carbon, 5% Super P, and 10% PVDF. This resulted in a 52.50 mg hard carbon, 3.088 mg Super P, 6.176 mg PVDF, and 500 microliters NMP mix for the cardboard and a 33.20 mg hard carbon, 1.953 mg Super P, 3.906 mg PVDF, and 300 microliters NMP mix for the leaf. The slurries were mixed by alternating two minutes on the Vortex Genie and then 10 minutes in the sonicator for 3 to 4 cycles. At first, a Ni mesh was used as an electrode. 8 0.5 in diameter circles were punched out of a sheet of Ni mesh and were cleaned with deionized water and acetone. 60 microliters of slurry were piped onto the mesh circles, four for each the leaf and cardboard. The slurry was too thin to properly integrate into the mesh, so a different substrate had to be used. 1 cm by 1 cm copper sheets were cut out. They were massed and then 60 microliters of the slurry mixture was dripped on using a micropipette. The coated sheets were heated in a vacuum oven at 60 degrees Celsius overnight. Afterwards the cells were constructed in a glovebox on a Kimwipe. The electrode was placed onto the cell bottom with the copper side facedown. Then a separator and 100 microliters of NaPF6 PC/EC electrolyte solution was added. On top of that a stainless steel current collector and a piece of potassium was placed. The argon atmosphere in the glove box prevented the potassium from reacting with oxygen. Then another separator, a wave collector, and the cell top was put on. The cell was placed and centered on a compression machine. The pressure was increased to about 1000 PSI and then it was all released and the cell was retrieved. The side vent was vacuumed out and then the cell was taken out to ensure no oxygen would enter the glovebox environment. The same procedure was repeated for all the coin cells. Analysis A bit of the hard carbon powder for each sample was saved to use for analysis. A Raman microprobe analysis was run on Super P and both hard carbons to compare the order and vibrations of molecules to determine if it was truly a hard carbon with a more porous morphology. Infrared spectroscopy was also run to determine if hard carbon exhibited a similar structure to the normal carbon. X-ray diffraction was the last analysis run on the samples, which was to ensure the molecular structure of the hard carbon differed from graphite. SEM microscopy was the final analysis run to get a visual representation of the hard carbon. The battery coin cells were taken and attached with clamps to a current measuring device. A computer program would charge and discharge the cell and take measurements based on a set of given parameters. The cell’s efficiency was measured by recording voltage and examining the continuation of charging and discharging cycles. The results were controlled against the standard potassium air battery coin cell. Results The hard carbon synthesis was successful for both the leaf and the cardboard. The samples exhibited significant deviation from graphite in the analyses. Figures 1-3 display the difference in results for the analyses. Figure 4 clearly shows a different morphology of the hard carbon samples compared to graphite under SEM. The hard carbon has a more chaotic morphology with vacuous spaces in between while the graphite is a clearly layered and more rigid structure. The hard carbon from both the leaf and the cardboard was then applied in potassium air battery coin cells for testing. The samples were compared against a standard potassium air battery coin cell to ensure proper function and hopefully efficient application. All the coin cells were tested for voltage and capacity and length of charge/discharge cycles. Figure 5 shows the different voltage-capacity profiles for the cells. Although the standard coin cell was slightly better in terms of efficiency, the different hard carbon coin cells showed promising results. They had slightly less voltage, but seemed to still be able to function perfectly fine, even using waste and organic materials like leaves and cardboard. In Figure 6 the charge and discharge cycles are being compared between the cells. A major issue with all oxide batteries is the degradation of the electrolyte and the formation of an insulating layer on the metal electrode. The constant flow of oxygen and side products through the electrolyte causes degradation, and at the electrode the side products react to form an insulating potassium layer on top of the electrode. The layer prevents continued efficient diffusing of potassium in the cell, thus severely limiting the life cycle of the cell. The hard carbon actually improved the life cycle of the cell and kept up more consistent charge and discharge cycles over the control cell. Discussion/Conclusion Battery technology is becoming ever more important as a field of research. With the dwindling supplies of fossil fuels, new sources of energy need to be utilized and more efficient ways of using and storing that energy need to be developed. Different battery types are being refined and experimented on. This study focuses specifically on the potassium air battery, a potentially useful battery in the future due to its high specific energy and stability from low overpotentials. This study addresses on the longevity problem of the potassium air battery by applying hard carbon synthesized from leaves and cardboard, which are easily obtainable organic and waste products. The hard carbon was effectively synthesized and had a much different morphology from graphite. Through the different analyses, it could be seen that the hard carbon synthesized from both leaves and cardboard was much more chaotic and had more vacuous spaces in its morphology while graphite were clearly layered and orderly. The utilization of the hard carbon still allowed the potassium air battery coin cells to function correctly, although at a slightly lower voltage level. This could have happened because the cell was not able to maximize the first charge cycle since the flow of electrons through the cell might be disrupted slightly by the hard carbon morphology. However, the hard carbon cells actually ended up having more consistent charge and discharge cycles as time progressed, which meant they provided better cell life and longevity. That was one of the fundamental issues of a potassium air battery because of the degradation of the electrolyte from diffusion of oxygen and side products, as well as the formation of an insulating layer on the electrode from the side products reacting with potassium. However, in this study, the hard carbon actually helped the issue, since the flow of potassium ions is much improved. With graphite, potassium ions are unable to integrate smoothly in the cathode region since the layered sheets are not accommodating enough for the size of the potassium ions. However, because the hard carbon has a much more variable morphology, there are many spaces for potassium ions to fit into and reduces the formation of the insulating layer, thus allowing for more long term function and consistent charge and discharge cycles. This study is also subject to some limitations. Most of the results found were due to the application of hard carbon. There were not many significant results drawn between hard carbon synthesized from leaves or hard carbon synthesized from cardboard, so it’s difficult to tell what difference the source of carbon makes. Also, the study was mainly focused on whether hard carbon would be applicable in the battery, and not so much the efficiency of the battery. There could be more analyses conducted about different variables of battery function between the hard carbon cell and the control. This could be even further extended to comparing it against commercial batteries to determine what the next step to improving viability of the potassium air battery is. However, this study did yield promising results for the application of hard carbon and opens up many possibilities for future research. References Buiel, E., & Dahn, J. R. (1998). Reduction of the irreversible capacity in hard-carbon anode materials prepared from sucrose for Li-ion batteries. Journal of the Electrochemical Society, 145(6), 1977-1981. Buiel, E., George, A. E., & Dahn, J. R. (1998). On the reduction of lithium insertion capacity in hard-carbon anode materials with increasing heat-treatment temperature. Journal of the Electrochemical Society, 145(7), 2252-2257. Gautier, S., Leroux, F., Frackowiak, E., Faugere, A. M., Rouzaud, J. N., & Beguin, F. (2001). Influence of the pyrolysis conditions on the nature of lithium inserted in hard carbons. Journal of Physical Chemistry, 105, 5794-5800. Ponrouch, A., Goni, A. R., & Palacin, M. R. (2013). High capacity hard carbon anodes for sodium ion batteries in additive free electrolyte. Electrochemistry Communications, (27), 85-88. Ren, X., & Wu, Y. (2013). A low-overpotential potassium-oxygen battery based on potassium superoxide. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 135, 2923-2926. Stevens, D. A., & Dahn, J. R. (2000). High capacity anode materials for rechargeable sodium-ion batteries. Journal of the Electrochemical Society, 147(4), 1271-1273. Han, Sang-Wook, et al. "Effect of pyrolysis temperature on carbon obtained from green tea biomass for superior lithium ion battery anodes." Chemical Engineering Journal 254 (2014): 597-604. Naskar, Amit K., and Zhonghe Bi. "Tailored recovery of carbons from waste tires for enhanced performance as anodes in lithium-ion batteries." RSC Advances 4 (2014): 38213-21.