Langue/Parole Greig E. Henderson and Christopher Brown (2013

Structuralism:

Langue/Parole

Greig E. Henderson and Christopher Brown (2013)

A theory of literature that focuses on the codes and conventions that undergird all discourse and on the system of language as a functioning totality. This system

Ferdinand de Saussure calls langue, "the whole set of linguistic habits which allow an individual to understand and to be understood." Anticausal and antiphilological, structuralism deliberately ignores the historical origins of the various elements of language, the external context of linguistic acts, the agents who use language, and the individual speech acts themselves (parole).

Structuralism sees language as a system of differences without any positive terms, embraces the arbitrariness and conventionality of the sign, brackets any consideration of the referent, and generates a vocabulary of oppositions, all of which are more or less synonymous: langue and parole, synchrony and diachrony, system and event, signifier and signified, code and message, metaphor and metonymy, paradigm and syntagm, selection and combination, substitution and context, similarity and contiguity. In each case the first term is privileged.

Although Saussurian linguistics is its paradigm, what is of interest is how structuralism analogically extends Saussure's terms into the analysis of literature.

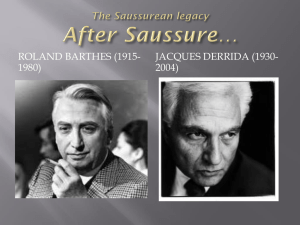

Roland Barthes provides a good example. "Literature" Barthes writes, "is simply a language, a system of signs. Its being [être] is not in its message, but in this

'system.' Similarly, it is not for criticism to reconstitute the message of a work, but only its system, exactly as the linguist does not decipher the meaning of a sentence, but establishes the formal structure which allows the meaning to be conveyed." Rather than interpreting the meaning or value of a work, the critic examines the structures that produce meaning. The intentionality of the author is thereby disregarded; language and structures -- not the consciousness of an author or the willed verbal acts that eminate from it -- generate meaning.

As a consequence, the subject is dissolved into a series of systems, deprived of its role as a source of meaning, and thereby decentered. The self is an intersubjective construct, a place where codes and conventions interact. In addition, the reader is privileged at the expense of the author, for, as Jonathan

Culler points out, "the text is a kind of formless space whose shape is imposed by structured modes of reading." The operative concept is intertextuality. "We now know," Barthes writes, "that the text is not a line of words releasing a single

'theological meaning' (the 'message' of an Author-God) but a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash. The text is a tissue of quotations drawn from innumerable centers of culture."

Nevertheless, he goes on to say, "there is one place where this multiplicity is focused and that place is the reader, not, as was hitherto said, the author. The

Source URL: http://postcolonial.net/backfile/view?id=181

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/ENGL301-Langue-4.2.3.docx

© Greig E. Henderson and Christopher Brown, International Journal of Francophone Studies

(http://www.postcolonial.net/)

Used by permission.

Saylor.org

Page 1 of 3

reader is the space on which all the quotations that make up a writing are inscribed . . . . A text's unity lies not in its origin but in its destination." Codes, according to Barthes, equal the already read [déjà lu]; the reader is the place where the various codes are located. (See also Linguistics and literary theory,

Semiotics.)

Linguistics and literary theory:

The revolution in modern linguistics consists in regarding language synchronically rather than diachronically. Classical philology undertakes to construct a historical evolution of a system of language, focusing on the study of linguistic change over a period of time (diachrony), whereas modern linguistics studies the system as a functioning totality, a signifying structure (synchrony).

According to Ferdinand de Saussure, the pivotal distinction is between langue

("the whole set of linguistic habits which allow an individual to understand and to be understood") -- which Noam Chomsky calls competence ("what the speaker of a language knows implicitly") -- and parole (the individual speech act itself) -- which Chomsky calls performance (what the speaker does). The linguistic sign,

Saussure contends, is composed of the union between a signifier (an acoustic image which differentiates the sign from all others) and a signified (a concept or meaning). Affirming the relation between signifier and signified to be arbitrary and conventional, Saussure deliberately ignores the referent, the extralinguistic object to which the sign may or may not point. For Saussure, language is a system of differences without any positive terms. It has a vertical axis -- the paradigmatic, associative, or metaphoric axis -- and a horizontal axis -- the syntagmatic, contiguous, or metonymic axis. The former concerns the relations between an individual word in a sentence and other, similar words that might be substituted for it; the latter concerns the possibilities of syntactic combinations of words so as to make a well-formed sentence. All of the oppositions that structural linguistics generates -- langue and parole, system and event, signifier and signified, code and message, metaphor and metonymy, paradigm and syntagm, selection and combination, substitution and context, similarity and contiguity -- are variations of the opposition between synchrony and diachrony. In each case, the first term is privileged.

The application of this linguistic model to the study of literature has been fruitful.

Russian Formalism, semiotics, and structuralism analogically extend Saussure's terms into the analysis of literature. As Roland Barthes puts it, "Literature is simply a language, a system of signs. Its being [être] is not in its message, but in this 'system.' Similarly, it is not for criticism to reconstitute the message of a work, but only its system, exactly as the linguist does not decipher the meaning of a sentence, but establishes the formal structure which allows the meaning to be conveyed." Poststructuralism goes one step further, contending that if it is true, as structuralism maintains, that language is a system of differences without any positive terms, then the relational nature of signs produces a potentially infinite

Source URL: http://postcolonial.net/backfile/view?id=181

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/ENGL301-Langue-4.2.3.docx

© Greig E. Henderson and Christopher Brown, International Journal of Francophone Studies

(http://www.postcolonial.net/)

Used by permission.

Saylor.org

Page 2 of 3

process of signification. Deconstruction, therefore, tries to demonstrate how structuralism's focus on the systematic undercuts itself and how its privileging of langue over parole can be upset or reversed, leaving a free play of signifiers and an elastic context that can be infinitely extended. By contrast, speech act theory privileges parole over langue, seeing meaning as a species of the genus intending-to-communicate, as something use-oriented and context-dependent.

Rejecting the assumptions of theories based on the linguistic model. speech act criticism holds that the investigation of structure always presupposes something about meanings, language use, and extralinguistic functions. (See also

Semiotics, Speech act theory, Structuralism.)

Source URL: http://postcolonial.net/backfile/view?id=181

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/ENGL301-Langue-4.2.3.docx

© Greig E. Henderson and Christopher Brown, International Journal of Francophone Studies

(http://www.postcolonial.net/)

Used by permission.

Saylor.org

Page 3 of 3