Word 07

advertisement

Rough draft

WOMEN IN THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

INTRODUCTION TO THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

The Enlightenment was the necessary precursor to the French Revolution. At the various salons

hosted by saloniers, major discussions occurred on the need for France to be reformed in almost every area

of society: the economy, the church, education, taxation, voting, serfdom, freedom of speech, etc.

Historians of the French Revolution have debated for decades, which causes were the most important, but

everyone agrees that it was a multi causal event of momentous proportions of war, intrigue, violence, death,

starvation, unemployment, and incredible changes for not only the French people but for the people of

Europe too. One of the most famous 1789 pamphlets by Abbot Sieyes summarized succinctly the

frustrations of the third estate, which consisted of 98% of the population: “What is the third estate?

Everything. What has it been in the political order up to the present? Nothing. What does it ask? To become

something.” Later in another pamplet women will be referred to as the third estate of the third estate.

Financial reasons received the most reports, but bad weather was also a factor. Not only had Louis XIV

fought for over forty years in attempts to add more land to France, but these wars were worthless for only

the city of Strasbourg was gained. France’s financially support of the American Revolution because they

hated the British was another financial burden. With England’s successes against France in the New World

and England, France’s Empire was lost. Then a series of bad harvests late in the 1780’s caused widespread

distress in French cities and rural areas. Soaring bread prices left no money to buy manufactured items, so

unemployment became widespread. For centuries aristocrats had not paid taxes for their privileged

position. Louis XVI called the Nobles together, but they refused to cooperate. He had no other recourse, but

to call the Estates-General, France’s legislative body, that had not met for over 150 years, to work out

solutions. People, including women, drew up their grievances and proposals. Working women saw the

erosion of guilds as threatening their economic security. No police protection was available, and too many

men were trying to take over their time-honored work. Looking at the economic contributions of women at

this time, will be helpful to ascertain the hardships and concerns women endured.

WOMEN’S ROLE IN THE ECONOMY AT THE TIME OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

During the eighteenth century, as with previous centuries, working class women in the towns and

countryside (peasants or serfs) economic contributions were necessary to the survival of the family. Major

employment of women in towns depended on where in France they lived. In the city of Lyons silk

1

Rough draft

production was the mainstay of working women. In the Northern and Central parts of France, lace making

employed the largest numbers of young maidens and women both in the towns and countryside. Lace

making was one of the lowest paid positions for women, and tragically many of them eventually lost their

eyesight. Making thread out of both wool and cotton was also a major employer of women. A substratum

of poorer females in the towns did even more horrific jobs. They carried the night soil, wood, food, and

water, basically anything that was portable. In the larger cities they sorted rags, were refuse collectors, and

were assistants to masons and bricklayers. Besides the usual activities on the farms that women did like

milking the cows or goats, taking care of the garden and orchard, they also smuggled salt. Preservation of

food was necessary when fresh items were not available, and salt was the necessary ingredient for this

storage. French people had to gabelle or salt tax, which was extremely unfairly distributed. In Brittany, for

instance, where salt was plentiful, the tax was nil, where in other counties, it was impossible for peasants to

gather enough money to pay it. Thus, their recourse was to smuggle it. If the men were caught, they were

made galley slaves, but if the women were caught, they could not be placed on the ships, so the punishment

was less. There were caves where the females hid when the authorities were pursuing them. Caves were

and still are omnipresent in France in certain regions. If no work was available, women took to thieving,

drinking, and prostitution. All these labor intensive occupations took an enormous physical toll on the

women. When all else failed women they engaged in bread or food riots to keep their families from

starving. A famous saying ,“a bread riot without a woman is an inherent contradiction,” entered France and

other countries. Husbands deserted their wives and children in great numbers too , before and during the

French Revolution, as they were unable to support them. This was true during the Great Depression in

Europe and America too in the twentieth century. England had a “poor relief “ plan to aid the destitute in

the individual parishes beginning with the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, but France did not.

CONTRIBUTIONS OF WOMEN DURING THE REVOLUTION

Women were involved from the beginning in the various events and activities of the French

Revolution, but in smaller numbers than men. Women’s contributions came from all levels of society,

whereas men’s involvement came mainly from the top tier of the third estate. The destruction of the

Ancient Regime, as French Absolutism was called had several key occurrences. Louis XVI, recognizing

that France was in a severe financial crisis, called the Assembly of Notables. Here the three estates met

with the third estate demanding a change in the voting structure of the Estates General, the representative

body for France. Each estate could cast one vote, but the first two estates voted as one since they were the

wealthy churchmen and nobility. The third estate represented 98% of France from merchants and lawyers

2

Rough draft

at the top to the homeless poor at the bottom. French serfs and peasants made up the majority of the Third

Estate, but only owned one-third of the land, and were required to pay most all of the taxes. Back in the

Middle Ages, the French nobility had voted to allow the French monarchy to have complete political

control with the caveat that these top two estates not have to pay any taxes.

Once the Third Estate recognized the hopelessness of their call for change in the voting mechanism,

they reassembled in the indoor tennis court, and in June 1789 vowed to not leave until they had a

constitutional monarchy. They now called themselves the National Assembly. Within a month a small

crowd decided to take matters into their own hands and attacked the Bastille. French historians generally

have signaled the beginning of the French Revolution with the Fall of the Bastille. The Bastille was a

medieval relic of a castle that housed few prisoners, but the people of Paris felt it was the symbol for

absolutism. This event occurred on July 14, 1789, and is now celebrated as France’s Independence Day

similar to America’s July 4th. Louis XVI then responded to this attack with some of his soldiers to gain

control, but it did not work as rumors spread to the countryside in the rest of France that his army was

going to attack the peasants next. This “Great Fear” resulted in the peasants rioting against their lords,

burning the manorial court records, and threatening the lives of the nobility. This “Great Fear” led to two

important consequences. All medieval feudal dues were abolished and the serfs were now free, but the

second consequence had a tremendous impact on the working class Parisian women. With the nobility

fleeing France in horror, their buying of luxurious goods came to a standstill, and severe unemployment

ensued for the women lace makers, silk, wool, and cotton workers. International trade was suspended and

austere fashions resulted. Elegant and bouffant dresses now were replaced by straight and untrimmed

garments. The numbers of poor and poorer were growing and the National Assembly did not offer any

“poor relief.” Men came to realize the problems were so immense that they could not solve them. Women,

meanwhile, became preoccupied with getting enough food for their family. They rioted for bread and price

controls, seized food and other goods. Women from the Parisian markets even sent a song to the National

Assembly with the following words: “If the clergy, if the nobility, my good friends treat us with such

rudeness and disdain, let them all fancy themselves capable of running the state while waiting, we will

drink to the third estate. By October 5, 1789 women were angry and agitated. It is estimated that 7000

women marched from Paris to Versailles to demand action for their plight. According to one eye-witness

account: “detachments of women [were] coming up from every direction armed with broomsticks, lances,

pitchforks, swords, pistols and muskets.” Their angst was directed towards Marie Antoinette, Queen of

France, and heatedly called “Madame Deficit.” Her husband, Louis XVI, had lavished on her palaces and

jewelry every time she had his child. Marie was the daughter of the Austrian Empress, Marie-Theresa, and

3

Rough draft

France hated Austria. Many historians are now signaling that this March on Versailles was the true

beginning of the revolution.

Meanwhile, the National Assembly accomplished its goal of writing a constitution, and declaring

France a constitutional monarchy. The monarchs were virtually prisoners of the people when this occurred,

and Louis acquiesced to the new form of government. With the demise of the nobility and absolutism,

Prussia and Austria declared war on France. This confrontation expanded and soon France was fighting

with the rest of Europe. This is when women of all classes contributed so much energy and their personal

goods to the revolution. Bandages for the wounded soldiers were made by the women’s household linen

and clothing. Women’s wedding rings were pawned for hard currency to clothe the soldiers. What was so

poignant of all was the psychological and physical gifts of their sons. Banners carried by these women

read: “J’ai donne un {deux, trios, quatre, cinq,) citoyen (s) a la Republique,” I have given a citizen (2-3-45) to the Republic.” Aristocratic women urged each other to contribute their jewelry to the King as a way

out of the financial dilemma. Women were involved politically as well. Pauline Leon established the

Society of Revolutionary Republican Women in May 1793. She was the wife of a prominent chocolate

manufacturer. Even the French actress Claire Lacombe became involved in this organization as well as

several hundred other women including some of the poor working class women. As one of the first

organized interest groups of working class women, they favored egalitarian policies and price controls.

Later when the Committee of Public Safety revolved into the Reign of Terror led by Robespierre, Leon’s

organization became an object of suspicion. When these same women donned the red cap of revolution,

and encouraged all other women to do likewise, the Jacobins who controlled the Committee of Public

Safety, closed it down by October with the following inane remarks: “Since when have people been

allowed to renounce their sex? Since when has it been acceptable to see women abandon the pious duties of

their households, their children’s cradles, to appear in public, to take the floor and to make speeches, to

come before the Senate? By now all women’s clubs and associations became illegal and again illogical

statements were made by the Jacobins: “In general women are ill-suited for elevated thoughts and serious

meditations…we believe woman should not leave her family to meddle in affairs of government.” Later in

the nineteenth century when there was practically a revolution of the month, political clubs were formed by

women. Some women even petitioned the government for them to be allowed to bear arms.

INDIVIDUAL WOMEN’S RESPONSES TO THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

Mary Wollstonecraft, the famous English writer of the Vindication of the Rights of Women, was

covered in the Chapter on First Feminist Movement in England, but deserves a few additional remarks

4

Rough draft

here. When she visited France during the French Revolution period, she read the women’s viewpoints on

the inequality of the genders. This obviously struck a chord in her, making her one of the most famous

women during this time frame.

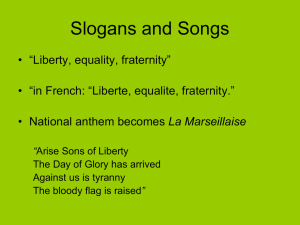

A few women made celebrated defenses of women’s right to “Liberty, Equality and Fraternity”, the

famous slogan of the Revolution. Made Roland (nee Marie-Jeanne Philipon 1754-1793) was one of the true

heroines of the French Revolution. She welcomed and fought for it. Marie, as the daughter of a Paris

watchmaker), married an older man, Jean-Marie Roland, who worked as a factory inspector. Both Marie

and her husband Jean were active Girondist leaders (the moderate group opposing the radical Jacobins).

Marie helped her husband win a seat in the National Assembly by writing his speeches. As she herself

stated: “I loved my country, [and] I was enthusiastic for liberty.” More promotions for her husband did not

make for more protection, and ultimately the terror came to them. Marie languished in jail for over a year

before she was sent to the guillotine, singing the French National Anthem Marseillaise and uttering words

that immortalized both her and her pronouncements: “O Liberty, what crimes are committed in they name.”

When her husband heard news of his wife’s death he committed suicide.

Olympe de Gouges, 1748-1793, a butcher’s daughter, became a playwright and writer. Early on she

supported the French Revolution, but she soon recognized that “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity” espoused

by male revolutionaries was meant for men only. One year into the Revolution, she published Declaration

of the Rights of Women”, which was modeled on the Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen, where all

men were free and equal, freedom of speech, etc., principles outlined in the British Bill of Rights and the

U.S. Constitution and Bill or Rights. In Olympe’s work she called on women “as mothers, daughters, and

sisters, representatives of the nation to constitute themselves a National Assembly.” She then elaborated on

Jean Jacques Rousseau’s idea of the general will and stated “the general will is to include female citizens

too.” Rousseau did not have a high opinion of women. While her writings went largely unread and unheard

of for the next one hundred and fifty years, they became the basis for the Seneca Falls Convention on

Women’s Rights, and closely paralleled Wollstonecraft’s work too. Because of her political activity, she

too was guillotined in 1793, but when on the platform, she yelled out to the women in the watching crowd:

“What are the advantages you have derived from the Revolution?”

Germaine de Stael, 1766-1817, was a French-Swiss woman of letters. She was the daughter of

Jacques and Suzanne Necker, mentioned earlier in “Women in the Enlightenment Age”. She clearly

connected with her mother’s salon, absorbing its intellectual and political atmosphere. In 1786 she married

Baron Stael-Holstein, a Swedish diplomat. Though moderately sympathizing with the French Revolution,

she left France in 1792, but coming back during the Directory. Setting up a salon that soon attracted

5

Rough draft

powerful political and intellectual people, when Napoleon came to power, she spiritedly opposed him. At

one point he said to Madame de Stael: “Women should stick to knitting.” This caused her exile, and she

went to her estate at Coppet on Lake Geneva, where she attracted another brilliant circle of important

persons. Writing novels with great success, soon led to Napoleon’s ordering the destruction of the entire

first edition (1811) of her comparison between German and French culture and mores in her book on

Germany. She was already a successful published author, but this book on Germany greatly influenced

European thought and letters of German romanticism. There are English translations of most of her works.

Probably the most famous woman during the French Revolution era was Josephine (1763-1814),

who became the wife of Napoleon Bonaparte, and later the Empress of the French in 1804 when he

crowned both himself and her. Her first husband was guillotined during the Reign of Terror. When she

married Napoleon he was a little-known artillery officer, but she became an important component in his

rise to fame and fortune. Her political and social connections gave Napoleon the opportunity to put his

career on the fast track to success. Josephine was born in Martinique, in the French West Indies. She went

to France in 1779 after marrying a rich young army officer, Viscount Alexander de Beauharnais. When he

was executed by the guillotine, she was left to raise their two children. As a widow reportedly she was

mistress to several leading political figures, but when Napoleon met her (she was six years older than he

was), her grace and charm attracted Bonaparte , and her political connections were an added bonus. One of

the early letters to her remarked: “I awake full of you. Your image and the memory of last night’s

intoxicating pleasures have left no rest to my senses.” In 1796 they married. Many of Napoleon’s letters to

her are still extant today, while few of hers have been found. We know that Josephine was less in love than

Napoleon, so maybe they do not exist. After her marriage, she apparently had an affair, and this cooled

Napoleon’s ardor. Unfortunately the marriage was childless and Napoleon wanted a son. In 1810 he

arranged for the nullification of his marriage to Josephine on the grounds that a parish priest had not been

present at the ceremony. Other sources say that it was a mutual separation . Soon thereafter Napoleon

married Archduchess Marie Louise of Austria. The French Senate awarded Josephine a large annuity, and

she retired to the chateau at Malmaison, near Paris. Napoleon was a frequent visitor there. Josephine loved

roses, and she set out to grow every variety in existence. Within a short time there were over 250 varieties

at Malmaison, where only twenty years earlier Linnaeus could only identify twenty rose varieties. Later her

daughter, Hortense, married Louis Bonaparte, Napoleon’s brother, and she became the mother of Napoleon

III, who would later rule France. Her son Eugene was an able and loyal general under Napoleon. Josephine

died at Malmaison in 1814, and Napoleon was greatly saddened. Through Josephine’s own children, she is

6

Rough draft

a direct ancestor of the present heads of the royal houses of Belgium, Denmark, Luxembourg, Norway, and

Sweden. Consequently her connections carried on for centuries.

WOMEN’S INVOLVEMENT WITH THE CATHOLIC CHURCH

Women during the revolutionary era became leaders in scorning the Catholic Church’s wealth and

disinterest in their plight. Their local parish priest was acceptable, but then they were not included in the

First Estates, made up of high clergy who had immeasurable wealth. However, once the Church lost power

at the end of the Revolution, (church land was confiscated), then women were instrumental in bringing

back the Church to France. Historians speak of renewed vigor of the church that trickled up from below.

Women forces Churches to reopen even in cities that were extremely anti-clerical like Paris. Catholicism of

1795 and beyond became visceral. Women queued to have their tongues scraped free of contamination of

masses of Constitutional Priests. Wives of fishmongers scrubbed out the parish church that had been

purchased by their husbands cheaply for use as a fish market. The Catholic Church became for the women

the symbol of traditional values and customs where babies were baptized, and weddings and funerals took

place.

NAPOLEONIC CODE OF 1804 AND ITS EFFECTS ON WOMEN

Once lauded for establishing civil equality among all men, feminist critics at the time of its

inauguration and now have objected to many of its provisions. What was so detrimental to women?

Napoleon directed that the writers of the Code look back in history to the Republic days of Ancient Roman

History, not the Empire Days when women were gaining more rights. In the Republic days of ancient

Rome, the patriarchal structure was in place. Napoleon thought the world would be a better place if the men

ruled over everyone. His philosophy of women was that they should be “confined to bed, family, and

church.” In the Roman Empire time frame, women possessed excessive dowries and inheritances to control

men, including using their sexuality to further ensnarl men. France thus needed to form the law of family

around a strong patriarchal man. Napoleon also thought that the Western beliefs of how a woman was

treated were all wrong. Easterners treated their women the correct way.

Women now acquired the nationality of their husbands upon marriage. Residence after the wedding

was determined by the husband. Women could no longer participate in law suits, serve as witnesses in

court, or as witnesses to civil acts such as births, deaths, and marriages. Men were no longer susceptible to

paternity suits as unwed mothers were prohibited from bringing lawsuits to establish paternity of their

children. Without these lawsuits, child support was automatically denied. Adultery was now only a crime if

7

Rough draft

committed by the wife, not the husband. The female adulterer was punished by imprisonment and fines,

unless her husband relented and took back his wife. No such sanctions were suffered by the husband, unless

they brought their new sexual partner into the home. Women had no control over any property, even if they

married under contract that ensured a separate account for the dowries. Husbands had administrative

control of the funds. Wages that wives made went directly to their husbands. If working class women

wanted to engage in business, they could not do so without permission from their husbands. Once a woman

gained permission, she did acquire legal status and could be sued, but her profits went to her husband.

When the business woman died, her property passed to her husband’s descendants not hers.

The one positive part of the code for women was that equal inheritance was not granted to sisters

and brothers. The Napoleonic Code influenced many legal systems in Europe and the New World. As

Napoleon conquered other countries of Europe, and placed his relatives on the respective thrones, the

Napoleonic Code went there too. Even the Louisiana Territory in the United States used the Napoleon Code

of Laws, and the state of Louisiana still uses it today. Comments from women ensued: “From the way the

Code treats women you can tell it was written by men.” Publications by women protested the sudden

repression of the Napoleon Code. Women publicly burned the Code when its Centennial was celebrated in

1904. Slowly women over the century regained back some of the restrictions of the Code, but it was not

until the twentieth century. France was one of the last European nations to grant women the right to vote –

in 1945.

8