Review Session Handouts with Sample Exam Writing

advertisement

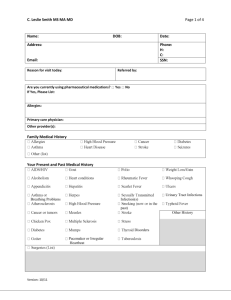

Practice with rhetorical terms. You should be able to point to the following in this piece: * Rhetorical question * narration * exemplification * description * paraphrasing The mistakes doctors make Errors in thinking too often lead to wrong diagnoses By Dr. Jerome Groopman | March 19, 2007 Dr. Jerome Groopman is chief of experimental medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and a staff writer for The New Yorker. A more extensive look at these ideas appears in his new book "How Doctors Think." Five years ago, a woman named Leslie developed indigestion, abdominal discomfort, and, occasionally, diarrhea. She has just given birth to her third child, and life was understandably hectic at home. Her primary-care physician gave her antacids, but this afforded only slight relief. "I feel really different. Something has changed in my body," Leslie told her doctor. But nothing abnormal was found on her physical examination or on routine tests. Leslie was sent to several specialists, and before each visit her primary-care doctor informed the consultants that Leslie was under "a lot of stress and seems anxious, and depressed." "Nothing is physically wrong," the doctors reassured Leslie. An antidepressant was prescribed, but it did not ameliorate her condition. Some four years later, Leslie felt dizzy and nearly fainted in the street. Her husband drove her to the local hospital, where she was found to be severely anemic. X-rays and scans showed a large mass where the small intestine meets the colon. Clearly, the tumor had caused her previous problems. Leslie is in her early 40s, an intelligent and thoughtful woman who told me her story in a clear and organized way. "I felt like I must be losing my mind," she said when recalling how her symptoms had been attributed to "stress and anxiety," and treated with an antidepressant. Upon reviewing Leslie's medical records, I found a blood test ordered by one of the specialists several years earlier that had been clearly abnormal and indicative of an intestinal tumor called a carcinoid. Her symptoms were consistent with this type of endocrine tumor, and, indeed, this proved to be the diagnosis at surgery. Misdiagnosis occurs in 15 to 20 percent of all cases, according to some research, and it is estimated that in half of these, serious harm occurs. Why do we as physicians miss the correct diagnosis? It turns out that the mistakes are rarely due to technical factors, like the laboratory mixing up the blood specimen of one patient and reporting another's result. Nor is misdiagnosis usually due to a doctor's lack of knowledge about what later is found to be the underlying disease. Rather, most errors in diagnosis arise because of mistakes in thinking. Physicians diagnose diseases based on what is called "pattern recognition." We draw bits of information from our patients' symptoms, our findings on physical examination, the laboratory tests, and X-ray studies the way a magnet pulls from all directions. To form patterns in our minds, we use shortcuts in thinking, so called "heuristics." Usually, a doctor generates one or two hypotheses about what is wrong within the first minutes of seeing the patient and listening to his or her story. Often, we are correct in these rapid judgments, but too often we can be wrong. Physicians are rarely taught about pitfalls in cognition. During their training, they work as apprentices to senior doctors. They learn largely by doing. In today's medical system, where there is intense pressure to see as many patients as possible, the quick judgment is often rewarded. Unfortunately, working in haste is a setup for errors in thinking. Only very recently have medical educators begun to focus squarely on the problem of misdiagnosis, why it occurs, and what might be done to prevent it. It turns out that errors in thinking do not occur in isolation, but usually arise from a cascade of sequential cognitive mistakes. I only learned this recently when I realized I did not know how I think; in fact, when I asked other clinicians how they succeeded or failed in making a diagnosis, very few could explain how their mind works to decipher a patient's problems. Let's deconstruct Leslie's case. Yes, the arrival of a third child can cause stress in a family. This truth strongly colored the physicians' impressions, so they made what is called "an attribution error." This involves stereotyping -- in Leslie's case , casting her as an anxious and somewhat depressed and distraught postpartum woman. The diagnosis of indigestion and abdominal discomfort with occasional diarrhea was too quickly fit into the pattern of a stress-related condition. The doctors fixed on this diagnosis, so called "anchoring" where the mind attaches firmly to one possibility. Anchoring so tightly to one diagnosis and not broadly considering others is called "premature closure." Even when, later in Leslie's evaluation, a blood test result was obtained that was very abnormal, it was not sufficiently considered; no one involved in her case could lift their mental anchor and comprehensively explore other possibilities. Discounting such discrepant or contradictory data is called "confirmation bias" -the mind cherry-picks the available information to confirm the anchored assumption rather than revising the working diagnosis. When I called one of Leslie's doctors, he was crestfallen that he had missed what was wrong. I knew all too well his feeling. Throughout my career I have made cognitive mistakes, some of them originating from an attribution error. All of us as physicians are fallible, and while it is unrealistic to imagine a perfect clinical world, it is imperative to reduce the frequency of misdiagnosis. I believe all health professionals should learn in-depth about why and how and when we make errors in thinking, and I also believe that if our patients and their families and friends know about the common cognitive pitfalls, they can ask specific questions to help us think better. We can interrupt the cascade of cognitive mistakes and return to an open-minded and deliberate consideration of symptoms, physical exams , and laboratory tests -and in this way close an important gap in care. Leslie was lucky, by the way. Her cancer turned out to be treatable, and she is doing fine. Sample Option 1: Two SQUAAT paragraphs joined together At the end of Peter Shaffer’s Equus, the psychiatrist Dysart tells Alan that he is going to “cure” him of his love and fear of horses. Dysart says to the audience, “I’ll take away his field of ‘Ha Ha,’ and give him Normal places for his ecstasy – multilane highways driven through the guts of cities.” (109). Put another way, Dysart will remove from Alan’s life his special ritual, with all its strange religious and sexual connotations, and will replace that ritual with the ordinary world, filled with boring old things like highways and convenience stores. Dysart’s metaphor about the roads being driven through the “guts” of cities seems interesting because it suggests a level of violence and connects to earlier parts of the play in which Dysart imagines cutting open children and removing their organs. The violence of this image suggests that Dysart is worried that he is doing real harm to his patients as he tries to “cure” him. It also seems important to note that Dysart is saying this to the audience. In many ways, they are the representatives of the Normal in this play and it is like Dysart is pleading with them to recognize all the terrible things about the normal world. With this ending, Shaffer seems interested in questioning whether it is worth it to exchange our deepest passions to conform to the normal world. While Peter Shaffer’s play is all about “curing” the abnormal world, Adrienne Rich’s poem “Aunt Jennifer’s Tigers” seems to celebrate the exotic, interior world of Aunt Jennifer. In lines 5 through 8, the speaker of the poem describes how her Aunt Jennifer’s hands are weighed down by “Uncle’s wedding band” but that when she sews the tiger tapestry her fingers “flutter.” The verb “flutter” implies that when Aunt Jennifer is making her special tigers, she is almost free of the oppressiveness of her marriage. Even though Rich’s poem, which is titled after Aunt Jennifer’s tigers rather than just Aunt Jennifer, seems to celebrate Aunt Jennifer’s freeing imagination, it seems worth noting that more of the images in these lines suggest that Aunt Jennifer is trapped. The needle is “hard to pull” and the ring sits “heavily upon her hand.” Through these descriptions Rich is showing how marriage can oppress women’s most vital imaginations. Sample Option #2: SQUAAT and then SOURCE paragraph or vice versa Jerome Groopman, chief of experimental medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, argues doctors need to slow down and be aware of common cognitive errors they can make. In “Errors in thinking too often lead to wrong diagnoses,” Groopman illustrates how simple errors in thinking lead to the 15 – 20% of misdiagnosis errors that occur, some of which have very serious consequences. One particular kind of error involves focusing too much on common patterns. Groopman tells the story of a woman named Leslie, who has just had her third child and who comes into the ER with abdominal problems. Groopman writes, “Yes, the arrival of a third child can cause stress in a family. This truth strongly colored the physicians' impressions, so they made what is called "an attribution error." This involves stereotyping -- in Leslie's case , casting her as an anxious and somewhat depressed and distraught postpartum woman.” Put another way, doctors focused strongly on the fact that the woman had jus had a third child and they used that fact to determine how they thought about the rest of their problem. Attribution errors occur when doctors “attribute” too much to one particular detail. This is sort of like when you meet a new person focusing on their nike sneakers and assuming they are athletic and then asking them questions only related to sports. Groopman shows just how dangerous this kind of error can be. In a similar way, the speaker in Yusef Komunyakaa’s poem “We Never Know” seems to fixate on a few key details about the person he has killed in battle. In lines 5 – 7, Komunyakaa describes a man that either he or his platoon has just shot. As he approaches the man’s body, he notices that the man is surrounded by a “blue halo / of flies” (5 – 6). This image suggests that he sees the dead man as somewhat heavenly, describing him as having an object associate with angels and heaven. Perhaps, this heavenly halo means that the speaker has realized that he has killed someone who was not, in fact, bad. Or maybe the description just speaks to a certain sense of guilt the speaker feels. It is also interesting how the peaceful image of the halo is almost immediately replaced by an image of destruction, as the flies scavenge for flesh. This image mirrors war itself, where moments of peace can quickly become deadly. Komunyakaa’s strong focus on details like the halo turning into flies suggests that in war, morality and right and wrong are become very complicated for soldiers and can change in an instant.