UNIVERSITY 1000 - Tennessee State University

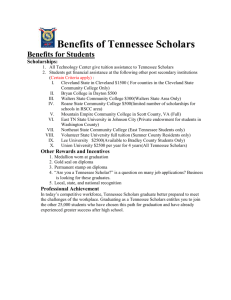

advertisement