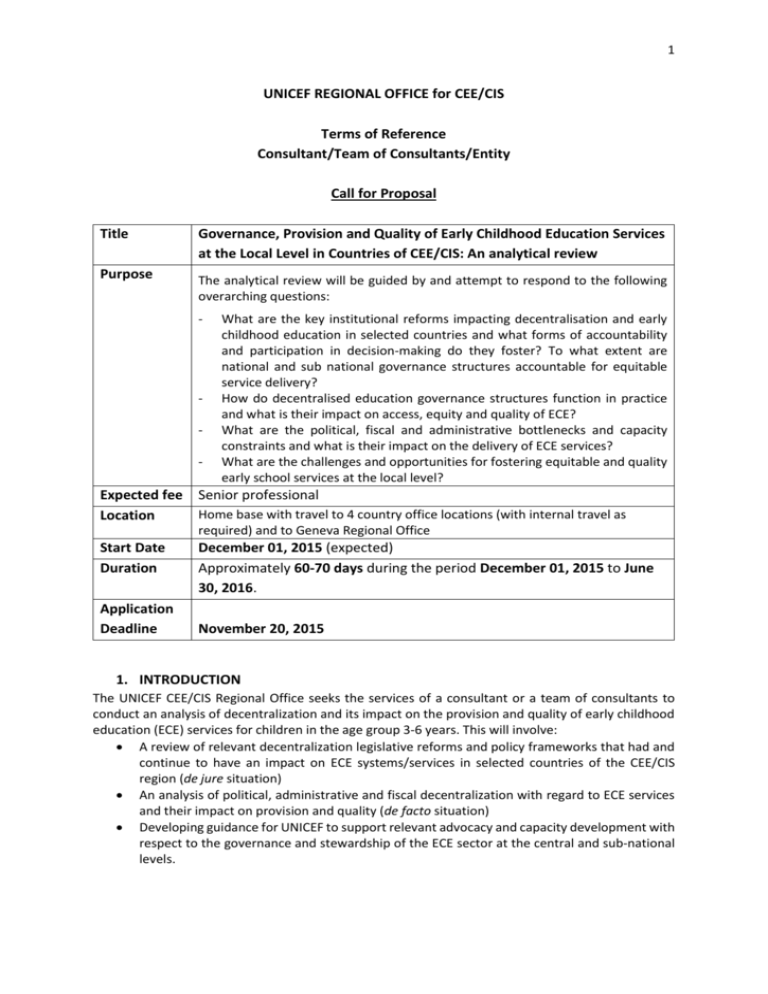

Terms of Reference

advertisement

1 UNICEF REGIONAL OFFICE for CEE/CIS Terms of Reference Consultant/Team of Consultants/Entity Call for Proposal Title Purpose Governance, Provision and Quality of Early Childhood Education Services at the Local Level in Countries of CEE/CIS: An analytical review The analytical review will be guided by and attempt to respond to the following overarching questions: - - What are the key institutional reforms impacting decentralisation and early childhood education in selected countries and what forms of accountability and participation in decision-making do they foster? To what extent are national and sub national governance structures accountable for equitable service delivery? How do decentralised education governance structures function in practice and what is their impact on access, equity and quality of ECE? What are the political, fiscal and administrative bottlenecks and capacity constraints and what is their impact on the delivery of ECE services? What are the challenges and opportunities for fostering equitable and quality early school services at the local level? Expected fee Location Senior professional Start Date Duration December 01, 2015 (expected) Approximately 60-70 days during the period December 01, 2015 to June 30, 2016. Application Deadline Home base with travel to 4 country office locations (with internal travel as required) and to Geneva Regional Office November 20, 2015 1. INTRODUCTION The UNICEF CEE/CIS Regional Office seeks the services of a consultant or a team of consultants to conduct an analysis of decentralization and its impact on the provision and quality of early childhood education (ECE) services for children in the age group 3-6 years. This will involve: A review of relevant decentralization legislative reforms and policy frameworks that had and continue to have an impact on ECE systems/services in selected countries of the CEE/CIS region (de jure situation) An analysis of political, administrative and fiscal decentralization with regard to ECE services and their impact on provision and quality (de facto situation) Developing guidance for UNICEF to support relevant advocacy and capacity development with respect to the governance and stewardship of the ECE sector at the central and sub-national levels. 2 This Request for Proposal emerges from the findings and recommendations of the 2014 Multi-country Evaluation (MCE) on Increasing Access and Equity in Early Childhood Education. The MCE covered all UNICEF activities related to advancing Early Learning and School Readiness (ELSR) efforts for children in the 3-6 year age group and covered the period 2005 to 2012. Five countries and one territory participated in the MCE: Armenia (Ar), Bosnia and Herzegovina (BH), the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FMa), Kosovo (under UNSCR 1244 - Ko*), Kyrgyzstan (Kg) and Moldova (Mo). The MCE concluded that while, “the basis of the ELSR sector has been institutionalised within governments and legislative frameworks not only within the education sector but also in wider national priorities and strategies…issues of decentralised implementation, coherence, equity and alignment with EU requirements will be key challenges for the future.” One of the principal recommendations of the MCE was: … that UNICEF strengthen its ability to navigate decentralisation and to provide sustainable capacity development support to system institutions at national and sub-national levels. In particular, this would involve developing stronger partnerships with line ministries in charge of decentralisation and planning, and with sub-national levels to strengthen understanding and influence on budget allocation, disbursement and practices. The evidence gathered and analysed through this planned analytical review will be used to: inform discussions regarding priority areas for improving access, equity and quality in decentralised ECE systems across the region; support sustainable capacity development at national and sub-national levels; assist UNICEF country offices in reconfiguring and developing relationships with partners to bring technical support and institutional capacity development to sub-national units, and refine programmatic approaches that UNICEF can support to foster ECE in selected countries 2. BACKGROUND Existing evidence on early childhood care and education indicates that children from disadvantaged backgrounds have the most to gain from attendance in early childhood programmes and that inclusive early childhood services can have a strong impact on equitable life chances. Disparities in school readiness mean that some children start primary school already behind. These disparities persist and even widen during the school years with higher risks of low performance, repeating grades and dropping out of education. Early Learning and School Readiness in CEE/CIS Following the collapse of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia and the loss of social subsidies, most of the countries and territories of the CEE/CIS region were unable to sustain early childhood services (many of the cooperative workplaces were closed or changed ownership) and there was a crisis of transition for early childhood education and care because of lack of funds, structure and political will. Many kindergartens were closed, with those remaining often concentrated in urban areas and reliant on informal payments to compensate for state under-funding and low salaries, throwing up additional barriers to access for poor and marginalised groups. At the same time, the legacy of Soviet and Yugoslav provision established expectations of kindergartens providing full day care and education. As countries and territories in the region attempted to make the transition from the collapse of former systems, this legacy has biased efforts towards the maintenance and restoration of the old 3 infrastructure of kindergartens and the use of much reduced budgets on programme models that are unaffordable for widespread, equitable access and delivery at scale. As a result many children’s rights to preschool education are not being met across the region. Decentralisation in CEE/CIS State socialism was not a uniform experience in the region, and there were differences in historical backgrounds with respect to the extent and nature of centralisation. For example, in the Soviet Union periods of more centralised economic management alternated with less centralised periods such as the sovnarkhoz reforms of the late 1950s and perestroika of the late 1980s. Outside the SU, Albania was highly centralised and Yugoslavia less so. Countries reacted differently to the transition in terms of how and at what speed decentralisation was undertaken, depending on the political orientation, proximity to the EU, and level of institutional development. Decentralisation is at the very core of governance; at its heart are issues of rights (who is entitled to what), responsibilities (who must deliver what), and accountabilities (who is held accountable, by whom, and how). Within these governance relationships, the nature of decentralisation also largely determines the efficiency and effectiveness of spending, defining how much is spent, who has discretion over inputs, outputs, and outcomes, and what incentives are in place for delivery. There are some common features of decentralisation across the region. Firstly, there is a general antipathy towards highly centralised systems, which were historically associated with external control over national sovereignty, the failure of the state to deliver services in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union and Yugoslav Republic, and in many instances the ability of the centre to hold the country together peacefully. As a result, many adopted decentralised local government structures quite rapidly in the early 1990s, as set out by the European Charter of Local Self Government. Decentralisation was also seen as a panacea for social problems but the collapse of government revenue coupled with very high unemployment meant that new schemes developed crisis symptoms requiring reform even before they could fully develop. Furthermore, these rapid moves to decentralise took place even before well-functioning democratic governance had been established at the central level and in environments with no prior experience in decentralised management of public services. Some of the major challenges that are common throughout the region are: The lack of comprehensive and consistent strategies for decentralisation; Inadequate (or entirely absent) policy coordination mechanisms; and Excessive fragmentation of local government structures; and Very high levels of unfunded mandates with respect to critical aspects of child rights realisation (especially pre-school but also primary education, social services, and in some instances social assistance). Local governments are still extremely weak in their capacities and their empowerment vis a vis central government, thereby limiting their ability to negotiate strongly with the centre on responsibilities and the sharing of revenue. Furthermore, and perhaps most importantly, some of the ‘governance basics’ are still missing, in terms of a public administration with a culture and norms supporting democratic and effective delivery. The effective application of power-sharing principles has been slowed down by specific obstacles, among which: (1) strong dependence on the state, (2) mistrust among agencies and levels of government, (3) lack of political commitment, (4) fear of losing control, (5) lack of 4 comprehensive educational strategies, (6) weak management capacities, and (7) resistance to change and to take on greater responsibility.1 The Impact of Decentralization on Early Childhood Education Broadly understood, the decentralisation of early education systems is an example of the principle of power sharing - both horizontally and vertically. It is the allocation of responsibility for policy-making, oversight and delivery across different government departments and levels, and might comprise market decentralisation when educational services are provided by the private sector alongside public authorities. The decentralisation of early childhood education systems can act both as a threat and as an enabler. Under frequent reforms driven by political changes, it can lead to fragmentation, overlapping responsibilities across agencies, inconsistencies in policies and uneven implementation at the local level. As an enabler, it brings decision-making closer to those that are being served, allows for flexibility for local needs, promotes local development of policies and reduces bureaucracy.2 A 2006 OECD study - limited to upper-income countries, the majority of which have consolidated the responsibility for all forms of early childhood education and care under one ministry - lists among the positive consequences of decentralisation the integration of early childhood education and care at the local level and greater sensitivity to local needs. 3 Historically early education has not been a “central” subject in CEE/CIS and with the transition and the closing down of factories and enterprises, ECE suffered a huge shrinkage. It never quite recovered as it has often fallen through the crack between national and sub-national governance structures. Based on traditions of state-funded care, the countries and territories of the CEE/CIS region, share similar instructional visions, but have adopted a plethora of approaches to decentralisation linked to different starting points, differentiated rationales and meanings of reforms. This has generated a varied picture of early childhood education provision, comprising political (devolution), administrative (deconcentration), fiscal and market transfers of responsibilities. A variety of key ECE functions, including goal setting, resource allocation, quality assurance and accountability are currently situated on a continuum from local discretion to central monitoring, with important differences between the formal situation (de jure) and its application in practice (de facto). While the concrete legal provisions can be identified more easily, the specific application of policy frameworks amidst complex governance structures remains more difficult to grasp, but fundamental for addressing structural inefficiencies in a meaningful way. Over the past decade in the CEE/CIS region, governments have been strengthening or rebuilding national and decentralised systems for ECE with some countries, such as Moldova, achieving significant expansion. However, coverage in many cases remains low with significant gaps in access. Equity considerations are yet to be mainstreamed in the day-to-day practices. This will require equitable financial mechanisms, significant strengthening of decentralised capacities, stronger and more nuanced recognition of disaggregated marginalised groups’ needs and integrated modalities to meet these. All the countries covered in the MCE have implemented decentralised preschool education systems to various extents, with compulsory provision in Mo, FMa and Kg and improved legislative provisions and complementary services in Ar and Ko*. While financial and administrative decentralisation have 1 Radó, Péter (2010) Governing Decentralized Education Systems : Systemic change in South-Eastern Europe, Budapest: Local Government and Public Service Reform Initiative, Open Society Foundations 2UNESCO (2007) EFA Global Monitoring Report. Strong Foundations: Early childhood care and education. Paris: UNESCO 3 OECD (2006) Starting Strong II : Early Childhood Education andn Care. Paris : OECD, pp. 51-52. 5 progressed, governance and accountability for ECE have mostly not been transferred to the local level yet. There has been some improved budget and expenditure reporting for the sector but the complex arrangements under decentralisation mean that many obstacles remain. Budgetary responsibility for preschool has been decentralised (to municipalities or local authorities) in most countries of the region. However, the plethora of mechanisms for fund transfers, ranging from block grants are made to municipalities based on number of kindergartens (Ko,* and Mo) to allocation of per capita funding for pre-primary children (Ar, Kg) pose many challenges to the provision, accountability and transparency of ECE systems. Budget allocations for preschool at municipality level depend on the tax raising power of the municipalities and their leadership and implementation capacities, creating very uneven resourcing of the sector across local levels. This has proved problematic for the roll-out of alternative models of preschool provision. The administrative integration of ECE services across sectors, as well as the cross-sectoral policy development and planning remains a challenge, partly due to limited capacity among decentralised authorities. Whilst local governments have had opportunities to apply to a programme that would support expansion (Kg, Ar), there is little evidence of capacities and agency at local level to translate national goals into local interventions (Ko,* Ar, Kg, Mo). There is evidence of municipalities also lacking capacity to experiment with different models of provision, particularly in urban areas where leaders appear more reluctant to provide non- traditional provisions (FMa, Kg, Ar). However, where there has been local political support and individual capacity and interest in ECE, municipalities have been successful in leveraging resources and building strong relationships with communities around preschools with good examples observed in a number of countries. This uneven level of implementation and resourcing has important implications for equity and points to weaknesses at a system level for preschool education that are part of broader government-wide decentralisation system bottlenecks. 3. RATIONALE UNICEF recognises access to quality ECE services as a critical contribution to overcoming disadvantage and inequity, and has committed to increasing its focus on this area in its most recent Global Strategic Plan for 2014-2017. Across the CEE/CIS region new impetus and emphasis has been brought to ECE through the Call for Action: Education Equity Now! launched in 2013 by Education Ministers from 17 countries in the region. As part of a broader education agenda, this Call for Action urges governments and their partners to accelerate progress towards ensuring that every child is learning early and enrolling on time. UNICEF has been working in partnership with governments, donors, nongovernmental organisations and civil society organisations to support transition to sustainable, quality ECE services, able to reach all children aged 3-6. Across the region UNICEF has focussed its programming at a national systems level, recognising that contributions to upstream system change and some downstream practice are the most effective routes to the progressive realisation of children’s rights. In spite of the critical role in social policy, decentralisation has not historically been recognised as a core area of UNICEF focus. This has been changing, however, as Country Offices are increasingly encountering decentralisation in areas such as: school optimisation and pre-primary education A new strategic guidance document (under preparation/finalization) notes that: In many countries across the region, responsibilities for ELSR service delivery have been decentralised to sub-national administrations with the aim of bringing services closer to communities and making them more responsive to local needs. With uneven and inadequate capacities and resources, however, many 6 decentralised authorities have struggled to deliver on their responsibilities for ELSR, increasing the risk of inequitable growth and weak quality assurance. This is a significant bottleneck to translating national system changes (such as new ELSR policies) to positive impacts on the lives and rights of children. Strengthening broad processes of decentralisation, public administration and institutional reform is essential to develop the capacities of the decentralised system. Within this it is important to ensure that these processes are informed by considerations of quality and equity for ELSR service delivery. Building on the lessons and experiences from the past decade, and the recommendations of the MCE, UNICEF is plans to bring a renewed strategic focus to its ECE programming, alert to the fact that due cognisance must be given to the barriers and enablers with which decentralized social services are associated. 4. OBJECTIVES The analytical review will be guided by and attempt to respond to the following overarching questions: a) What are the key institutional reforms impacting decentralisation and early childhood education in selected countries and what forms of accountability and participation in decisionmaking do they foster? To what extent are national and sub national governance structures accountable for equitable service delivery? b) How do decentralised education governance structures function in practice and what is their impact on access, equity and quality of ECE? c) What are the political, fiscal and administrative bottlenecks and capacity constraints and what is their impact on the delivery of ECE services? d) What are the challenges and opportunities for fostering equitable and quality early school services at the local level? and with particular regard to functions, funds and functionaries e) Division of responsibilities: How is responsibility for policy direction, legislation, regulation, planning, management, revenue raising and resource allocation, coordination, quality assurance, and monitoring and evaluation divided and shared between the national and subnational levels? f) Financing: From which sources are the responsibilities funded (locally-collected taxes, user fees, taxes collected by the centre but shared with local level, central grants)? How much discretion does the decentralised agency have over spending decisions? What criteria are used in allocating resources at the national and sub national levels, and to what extent are these criteria responsive to equity considerations? g) Administration: Who has control over decisions to hire, fire, and promote staff, set salary levels and working conditions? How is responsibility for infrastructure, maintenance, and procurement assigned? The review will provide recommendations for UNICEF’s continued involvement in issues of access, quality and equity in ECE at sub-national level in the target countries. It will be used to reinforce the CEE/CIS RKLA 3/4, revise the Theory of Change to incorporate decentralized system issues, and address the challenges of decentralisation and privatisation of early school education services. 7 5. MAIN TASKS The consultancy will be expected to perform the following tasks: Mapping the institutional reforms impacting the decentralised decision-making and delivery of early childhood education services in the last decade in each of the countries studied and their effects on different groups of vulnerable children (children with disabilities, ethnic minorities, poor, rural residents, etc.) Analysing the distribution between the centre and local levels of roles and responsibilities, accountability, decision-making and quality assurance mechanisms – with regard to governance, financing and implementation of preschool education services (provided by both the public and private sectors). Identify the political, fiscal, and administrative bottlenecks and capacity constraints for equitable decentralised pre-school education systems in the selected countries Identifying potential strategies for engagement including policy priorities for decentralised levels based on needs assessment (with the help of country offices) Identifying good practices for the delivery of ECE services at sub-national level both from the region as well as from advanced economies. 6. COVERAGE Four countries – one each from Central Asia; the Balkans; the Caucasus; and, western CIS. The countries will be selected based on several criteria including their sub-regional representativeness and different models of decentralization. Fieldwork/interviews will be conducted both in the centre and in selected localities. Localities will be selected on the basis of criteria including: distance from centre; wealth status; population; and so on. Stakeholders that will be covered will include: officials from relevant ministries (Education; Regional Administration; etc.); local authorities; preschool directors and educators; community leaders; parents. 7. ISSUING OFFICE Early Childhood Development Section, in collaboration with the Social Protection Section, UNICEF Regional Office for CEE/CIS, Geneva 8. SUPERVISOR The consultant(s) will report directly to the Regional Advisor, ECD, Dr. Deepa Grover. 9. QUALITY ASSURANCE Social Protection Section and the Regional Knowledge and Leadership Area – No. 3/4, Regional Reference Group. 10. DELIVERABLES The Table below describes the timeframe and deliverables. The exact dates of the consultancy assignment will be decided upon based on the availability of the consultant/s and convenience of selected country offices. Below is an indicative time line. 8 Deliverable Annotated Outline/Inception Report – including analytical framework (10 pages) Country Visits x 1 (Brief Trip Report) Country Visits x 3 (Brief Trip Reports) First draft (40-60 pages with examples with proposed amended Theory of Change) Final draft (60 pages) Power Point Presentation 11. TIME LINE 60-70 days during the period 01 December, 2015 to 30 June, 2016. 12. COMBINATION OF TECHNICAL COMPETENCIES AND QUALIFICATIONS REQUIRED FOR THIS CONSULTANCY Advanced university degree in child development and/or social sciences 8-10 years of extensive experience of public policy and public finance. Knowledge of governance and decentralization in relation to education systems Knowledge and experience of research in socio-economic issues in CEE/CIS region. Field experience in CEE/CIS countries is an asset. Record of academic research experience and/or written publications. Excellent written English language skills, demonstrable with samples of publications. Knowledge of Russian or any other language in the CEE/CIS region is an asset. Excellent drafting skills and ability to synthetize complex information and issues. Strong analytical and conceptual thinking. Ability to organize and plan own work following the established timeframes. Previous experience working for UNICEF an asset 13. TRAVEL The consultant/s will be required to travel to each of the 4 (four) selected countries for a period of 710 working days to conduct fieldwork and interviews at central and local levels. Consultant/s will be expected to make own travel arrangements including purchase of air tickets. UNICEF will be invoiced for travel costs at the end of each mission. The consultant/s will also be required to travel to the Regional Office in Geneva at least once to make a presentation of the Draft Report. Travel and daily subsistence allowances will be as per UNICEF travel rules and regulations UNICEF at country and regional levels will support travel and local facilitation (e.g. support for obtaining visas, identification of translators, identification of local facilitators, key stakeholders to be interviewed, etc.) 9 Any additional specific information regarding the time schedule, procedures, benefits, travel arrangements and other logistical issues will be discussed with successful candidate/s. 14. EXPRESSION OF INTEREST & ESTIMATED COST OF CONSULTANCY Together with an Expression of Interest, Curricula Vitae, UN P114, a Concept Note and Draft Plan, the consultant/s will be required to submit a detailed estimated budget including estimated travel budget and daily professional fee. All documents should be submitted by email to PETRONILLA MURITHI pmurithi@unicef.org by Friday, 20 November 2015. In the subject line of the email please state: Consultancy: ECE Decentralization 15. PAYMENT SCHEDULE 1. 30% prepayment of the total contract fee for inception report, Country Visit 1 and submission of the report of the pilot; 50% on submission of draft report and 20% on submission of final report. 2. UNICEF reserves the right to withhold all or a portion of payment if performance is unsatisfactory, if work/outputs is incomplete, not delivered or for failure to meet deadlines. Professional fees will be paid on the successful completion of specific tasks and the satisfactory submission of deliverables. 3. All materials developed will remain the copyright of UNICEF and that UNICEF will be free to adapt and modify them in the future. 4 P 11 form can be downloaded from http://www.unicef.org/about/employ/files/Personal_History_P11.doc