File - Jo Keogh Ceramics

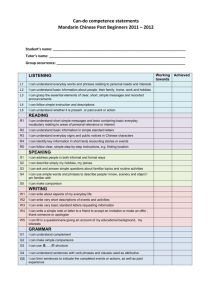

advertisement

Everyday things In the craft objects we use every day there exists a deep-rooted memory born of a necessity to satisfy the absolute physiological requirements of the human race. The need for sustenance, warmth and shelter underlie the most basic functions of craft objects and ‘while this purpose and these needs may be basic their implications are not’ (Risatti, 2007, p. 55). The ceramic vessel retains this fundamental meaning, an enduring convention of our human evolutionary moment, a memory that transcends ethnic, cultural and national, economic and class boundaries (Risatti, 2007, p. 59). As Premo Levi describes (1989, p. 33): 'man is a builder of receptacles; a species that does not build any is not human by definition... to fabricate a receptacle is due to two qualities which for good or evil are exquisitely human. The first is the ability to think about tomorrow... the second... is the capacity to foresee the behaviour of materials: if we keep to the subject of receptacles, we know how to foresee what container and content ‘will do’. The uncomplicated simplicity of pottery as a functional craft is contrasted with the more philosophical ideas of abstraction, symbolism, narrative. Pottery is 'the primal interweaving of matter, human action and symbol 1 that each pot represents' (Houston, 1991, p. 33). Even the earliest vessels can still move us through their expressive form. The advent of the potter’s wheel added rhythm and movement to the concept of the hollow form providing all the essentials of this most abstract art (Houston 1991, pp. 9 and 36). The words ordinary and useful now support a special role for the familiar forms of everyday pottery as the shape of a domesticated presence; the protecting features of the container connect with the concept of home (Houston, 1991, p. 9). Modern society has become estranged from the once holistic conception of daily life which been neglected and trivialised, eroded by the effects of modernisation, the dehumanising effects of technology, repetitiveness of work, and empty consumerism (Blauvelt, 2003, p. 18 and (Greenhalgh, 2005, p. 138). As a result, the social production processes of crafts has largely been lost and along with it many aspects of social consciousness and practice (Aratov, 1997, pp. 120-121). Industrialisation and mass production made it irrelevant for the craft movement to hold on to function as the core of its work (Dormer, 1994, p. 38) and the origins of everyday utilitarian ceramics have become hidden from the consciousness of modern consumer society. In a romantic reaction against industrial capitalism the craft potter came into existence, and in a bid to preserve historic values and traditional 2 skills (Frayling, 2011, pp. 65-66) the crafts have become ‘heavily encumbered with worthy and meaningful traditions’ (Houston, 1991, pp. 20-21). And so to an extent craft pottery remains outside its creative genesis, screened by tradition, taboos and truth to materials. The realm of the everyday is elusive, encompassing those activities, practices, spaces and things that exist beyond the reach of society’s official dictates and actions. By examining our everyday world anew we afford an opportunity to question what we take for granted in our everyday material world, challenge our presumptions about what is possible, reconsider our relationship to familiar things. In his appraisal of the practices of everyday life, the "arts of doing", De Certeau explores the dynamics of personal choice in terms of mass production and consumption through the theoretical framework of strategies and tactics (de Certeau, 1984). He describes the repressive techniques used by organisational power structures in modern society as ‘strategies’. Superficially, strategies exhibit indicators of the qualities of truth, permanence, and ubiquity, deployed against subordinates to elicit control. Despite such repressive aspects of modern society, there remains an element of creative resistance, ‘tactics’ enacted by ordinary subjugated individuals or "consumers". The “tactics” as defined by De Certeau are ways to artfully “use, manipulate, and divert” the cultural products and 3 spaces imposed by an external power. Tactics are simply ways of constructing alternatives as Certeau puts it "victories of the 'weak' over the 'strong'" (Certeau, 1984, p. 20). Certeau demonstrated this using the example of Spanish colonizers forcing their culture upon indigenous Indians; they did not reject or alter them but rather subverted them by using them for ends and references that the Spanish could not relate to or understand (Certeau, 1984, p. xiii). By comparison in consumer based society; the ‘common people’ have a culture imposed upon them by the ‘elites’ but often this culture is subverted by using its products outside of the original intensions of the producer. Thus for de Certeau, consumption is not passive but contains active elements of user resistance nonconformist, adaptive tactics that become creative acts in their own right. Creativity lies with the user and beyond the conventional role assumed by the producer. We must analyse the manipulation of cultural objects by ‘users’ other than its makers. In our haste to acknowledge the novel, the significant, the extraordinary we overlook the everyday, the basic, the familiar. Everyday objects form a paradoxical existence in our lives, they are omnipresent, yet we integrate these objects into our environment so successfully that they recede into the background against which we go about our daily lives. Georges Perec urges us to question the way we look at everydayness 4 (1997, pp. 205-207). 'How should we take account of, question, describe what happens every day and recurs every day: the banal, the quotidian, the obvious, the common, the ordinary, the infra-ordinary, the background noise, the habitual?' What is commonplace has become so familiar that we fail to even see it let alone question it, ‘this is no longer even conditioning, it's anaesthesia’ (Perec, 1997, p. 206). Perec described a re-imagination of everyday life, obliging us to question the customary commonplace stuff of everyday life, objects around us, places we inhabit, habits we form, routines we perform (Perec, 1997, pp. 206-207): 'what's needed perhaps is finally to found our own anthropology, one that will speak about us, will look in ourselves for what for so long we've been pillaging from others. Not the exotic anymore, but the endotic.' “what we need to question is bricks, concrete, glass, our table manners, our utensils, our tools, the way we spend our time, our rhythms. To question that which seems to have ceased forever to astonish us. We live, true, we breathe, true, we walk, we open doors, we go down staircases, we sit at a table in order to eat, we lie down on a bed in order to sleep. How? Where? When? Why?” In the decades following the Second World War the adoption of a systems based approach provided a means of appraisal and documentation of the world. This allowed a fresh level of engagement while offering theorists a 5 mechanism to manage and control organisations (Dezeuze, 2005, p33/34 and Boase, 2005, p67). By definition, a set of relationships between objects was considered a 'system' (Skrebowski, L., 2012). The use of simplified geometric forms, generative or repetitive actions and mathematical sequences were used to explore the role and relationship of systems and processes, their exposure, infiltration and insurrection, and this came to the fore in the evolution of art until the 1970’s (Dezeuze, 2005, p33/34, Perreau and Penwarden, 2005, p. 78, Boase, 2005, p. 67). From this principle came the concept of 'open systems'. Open systems are characteristically self-determining, lacking in order and predictability, enabling matter or energy to shift freely between the system and its environment (Spaid, 2005 pp. 54-55). Works that can be described as open systems are not displayed on the wall of a gallery or placed carefully on a plinth. Instead they are designed to be interactive and receptive to audience participation. The beholder becomes a part of the work and involved in the fabrication of its meaning (Perreau and Penwarden, 2005, p. 78, Boase, 2005, p. 67). Thus there is a conscious relinquishing of control by the maker, they become a ‘proposer’ of the piece instead of the producer of a finished work (Tate open systems exhibition, room 6: http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/opensystems/open-systems-room-6). Unpredictable, chance events influence the work resulting in multiple possible outcomes, including the risk of 6 damage and deterioration. (Spaid, 2005, pp. 54-55). Thus the works are designed such that the intensions of the maker can be subverted by the user. They acknowledge that the everyday is a participatory realm where design is incomplete; knowing that people will eventually inhabit and adapt what is given challenging the preconceptions of the maker. The Permanent Creation Toolbox of Robert Fillou, 1969 embodies the belief in audience participation, the human body is reintroduced within the realm of Conceptual Art (Dezeuze, 2005, pp. 33/34). Robert Filliou, 1969. Permanent Creation Tool-box. Available at http://www.garagecosmos.be/exhibition.php?id=4&lang=en 7 An example of open system thinking was DO, part the Dutch cooperative Droog Design, described as ‘an ever-changing brand that depends on what you do’. Mass production with an active role reserved for the consumer, an open nature that is out to mess with the everyday, obliging the user to confront the monotony of daily life by demanding interaction and conceptual creativity (Blauvelt, 2003, pp. 64-65). The ‘DO break’, for example, is a glass vase sheathed within transparent rubber. After you have bought it you smash it. The shards held in place by the rubber to give an exclusive vase. The ‘DO sit’ is an aluminium cube that can be beaten with a mallet, transforming it into a personalised seat. By evading fixed form, such works open a dynamic dialogue with the user, wise to the tactical habits of everyday. From a consumer perspective Baudrillard (1996, 92) proposes that the everyday object has two central functions, to be used or to be possessed. For the majority of consumers today, the accepted objects of their everyday will predominantly be mass produced items for use, yet, however purposeful these everyday objects may be, their mass production gives them a particularly unremarkable, generic status. Industry defines the form and function of the object and a long history of manufacturing has caused the everyday including domestic utilitarian ware to be “smoothed into near-featureless uniformity by relentless feeding to a global mass market” (Brown, 2007, p. 54) and these 8 “domesticated aesthetics” have been imprinted on our consciousness and still affects our orientation and judgement regarding what we like and admire (Cecula, 2008, p. 86). Droog. 2000. Do Break vase. Porcelain & rubber, height 34 cm. Image available at http://www.tjep.com/studio/works/products/do-break 9 A closer look at the processes whereby people relate to everyday objects reveals that often no conscious interpretation is needed as visible cues to their operation are usually present (Norman, 1990, p. 2). In general, we know what to do with an object just by looking at it. Affordances provide clues to function (Norman, 1990 pp.9-10), e.g. handles afford holding and lifting. Based on our experiences, conceptual mental models of novel objects are used to form explanations and simulate their operation, a complete knowledge is seldom required (Norman, 1990 p. 55). We understand the physical properties of ceramic objects, their surfaces are typically neat and reflexive, while form provides a handle or edge for gripping, a shape around which our hand fits with comfort (Ionascu and Scott, 2007 , p.86). Objects that are difficult to use provide no clues or false clues. False clues for example are seen in Luke Bishop’s Rongo Rongo series which aims to intentionally disturb the recognised syntax of function by disrupting the affordances of the object and Jaques Carelman's deliberately unworkable Coffeepot for Masochists. Frustration arises when the mental model of operation does not correspond to reality with loss of tacit understanding of the object. Objects that provide no clues may be without a clearly defined function. In the absence of information imagination can run free as long as the 10 mental models account for the facts as they perceive them (Norman, 1990, pp. 38-39) allowing us to reconsider our relationship with them. User participation, choice and potential rejection are vital elements of such objects and the possibility of new functions and rituals of use becomes an implicit quality, allowing purpose to be subject to a particular situation. The way objects are used is developed by and dependent on the operations and manipulations of their possessors, the maker simply provides a 'how and why of creation' deciding the features of their creations (Ionascu and scott, 2007, pp. 86-87. Luke Bishop. 2013. Rongorongo; Forgotten Function series; porcelain with latex additions; http://www.lukebishop.com/wordpress/?page_id=377 11 Jaques Carelman. 1969. Coffeepot for Masochists, originally in Catalogue d’Objets Introuvables (the Catalogue of Impossible Objects). Available from http://impossibleobjects.com/coffeepot-for-masochists.html In economies of the past the worth of goods was understood in terms utility value. In modern society, products are props in the staging of memorable moments of consumption, such an ‘Experience economy’ is what Jean Baudrillard refers to as sign value in which nothing represents itself literally. Things are barometers of wellness, competitiveness, wealth, prestige (Blauvelt, 2003, p. 16). The use of inexpensive everyday materials and things in the making of an object raises questions about the commercial value of the object whilst substance is added to the object, a more active connection with forms by creating a relationship between ourselves and our environment, a re-signification of ordinary everyday things that compels us practically and psychologically to reckon with them. 12 References Books Blauvelt, A., 2003. Strangely Familiar: design and everyday life. Walker Art Center. Baudrillard, J. 1996. The system of objects. Translated by J. Benedict, London: Verso. De Certeau, M., 1984. The practice of everyday life. Translated by S. Rendall, University of California Press. Dormer, P., 1994.The art of the maker. Thames & Hudson. Houston, J., 1991. The abstract vessel: forms of expression & decoration by nine artist-potters: Gordon Baldwin, Alison Britton, Ken Eastman, Philip Eglin, Elizabeth Fritsch, Carol McNicoll, Jacqui Poncelet, Angus Suttie, Betty Woodman: ceramics in studio. Bellew (with) Oriel/Welsh Arts Council. Houston, J., 1990. Richard Slee: ceramics in studio. Bellow. Risatti, H. A., 2007 1943.A theory of craft : function and aesthetic expression. University of North Carolina Press. Greenhalgh, P., 2005. The modern ideal: the rise and collapse of idealism in the visual arts from the enlightenment to postmodernism. V&A Publications. Frayling, C., 2011.On craftsmanship, Oberon. 13 Norman, D. A., 1990, The design of everyday things. Doubleday. Perec, G., (1997) Species of spaces and other pieces, translated by John Sturrock, Harmondsworth: Penguin. Journal Articles Aratov, B and Kiaer, C.,1997, Everyday life and the culture of thing (toward the formulation of the question), October, 81, pp. 119-28. Brown, L., 2012. Industry meets art. Ceramic Review, 255, p50-55. Cecula, M., 2008. Mass Production and Originality. Studio Potter 36 (2), pp 85-87. Ionascu A. and Scott D. Common Objects Common Gestures. Ceramics: Art and Perception, 2007, Vol. 68, pp 86-90. Spaid, S 2005, '“Open Systems”: Tate Modern, London UK', Artus, 11, pp. 54-55. Dezeuze, A 2005, 'Open Systems: Rethinking Art c1970: Tate Modern, London', Art Monthly, 288, pp. 33-34. Boase, G 2005, 'Open Systems: Rethinking Art c.1970: Tate Modern, London', Flash Art International, 38, p. 67 Perreau, Y, & Penwarden, C 2005, 'Open Systems: Rethinking Art c.1970', Art-Press, 317, p. 78 14 Web Skrebowski, L., 2012. All systems go: recovering Jack Burnham's 'Systems Aesthetics' [online] Tate papers, acessed 31.03.2014. available from: http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/allsystems-go-recovering-jack-burnhams-systems-aesthetics Open systems, room 6. Accessed 03.03.2014. available from: http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/opensystems/open-systems-room-6 Images Luke Bishop. 2013. Rongorongo; Forgotten Function series; porcelain with latex additions. Accessed: 29.06.2014. Available from: http://www.lukebishop.com/wordpress/?page_id=377 Jaques Carleman. Coffeepot for masochists. Accessed: 29.06.2014. Available from: http://impossibleobjects.com/coffeepot-formasochists.html Robert Filliou, 1969. Permanent Creation Tool-box. Accessed: 09.06.2014. Available from: http://www.garagecosmos.be/exhibition.php?id=4&lang=en Droog. 2000. Do Break Vase. Accessed: 09.06.2014. Available from: http://www.tjep.com/studio/works/products/do-break Word count: 2585 including references, 2206 excluding references 15