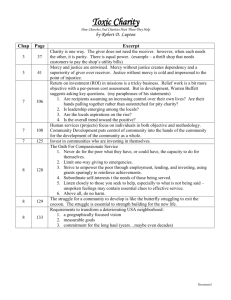

Lecture Notes

advertisement

Brandom 10/28/09 Sellars Week 9 Notes “Being and Being Known” (1960) “The Lever of Archimedes” (1981—First Carus Lecture) 1. TLA is a late, on the whole disappointing piece. (Certainly it was a disappointment as the opening one of the much-anticipated, much-delayed Carus lectures.) It is an intricate discussion of a 1949 essay of Roderick Firth, and of WS’s debate with Roderick Chisholm (the two ‘Roderick’s). It is a very careful, subtle, and sensitive working out of a dialectic, in which he shows great sensitivity to the possibilities of the positions with which he is disagreeing. 2. The 1960 “Being and Being Known” (BBK)—given the same year as “Phenomenalism”, just after the two 1959 GE lectures, and just before NS—tries to say what is right and what is wrong about the Thomistic neo-Aristotelian “doctrine of the mental word.” It is by far the most sophisticated discussion of this topic I have ever seen. I am an amateur with that scheme, needing to be guided by his account. He also has an intertwined discussion of Descartes, as insisting that “direct knowledge” of our sensations must be “non-analogical” knowledge of them. This is largely orthogonal to the main discussion (it sets up a final point functionalist point at [228] passage (37)), and I won’t say much about it. I’ll discuss two issues about this essay: a) A fascination passage on two kinds of logical “words”. b) The main discussion, which is summarized in the passage from [227] in (7) below, also at . I shall argue that a confusion between signifying and picturing is the root of the idea that the intellect as signifying the world is the intellect as informed in a unique (or immaterial) way by the natures of things in the real order. [218-9]. [218-9] at (22) in the Passages. As that passage makes clear, everything turns on the distinction between two kinds of isomorphism between words and world: picturing and signifying. So we must get clear about that. c) Throughout he works in a framework that distinguishes “the real order” from “the logical order”, or, apparently equivalently, “the intentional order.” Words regarded one way are in the real order and stand in picturing relations; regarded another way, they are in the logical-intentional order, and stand in signification relations. 3. Here is the focal passage on logic: [T]he intellect in first act has logical words in its vocabulary. Some of these logical words are, in the contemporary phrase, ‘truth-functional connectives’ (e.g. and and not), the most significant feature of which is that if a sentence or group of sentences is about the real order, the sentence which is formed from them by the use of these connectives is also about the real order. Thus Socrates is not wise is as much about the real order as Socrates is wise. Other logical words, e.g. implies in the 1 Document1 Brandom sense of logical implication, are such that sentences involving them are about the logical order, as is shown by the fact that these sentences require abstract singular terms (e.g. Triangularity implies trilaterality). [BBK-217] a) On the face of it, WS is making an astonishing distinction between bits of logical vocabulary: some produce statements sabout the real orders and some produce statements that are sabout the logical orders (which later on he identifies with—or maybe treats as species of the same genus as—the intentional order). b) Presumably the two-valued conditional, i) as a truth-functional connective and ii) as definable from negation and either conjunction or disjunction, is also “about the real order.” c) But what about non-truth-functional conditionals? Modal conditionals, or just those that are counterfactually robust, are, he tells us in CDCM, covertly metalinguistic, conveying inferential commitments involving expressions related (in a dot-quote way) to the sentences appearing as antecedent and consequent of the subjunctive or counterfactual conditionals. d) ‘Implies’ is often used in an explicitly metalinguistic way, as in: “‘It is raining,’ implies ‘The streets will be wet.’” And WS thinks it is covertly metalinguistic in “That it is raining implies that the streets will be wet.” For he thinks ‘that’-clauses express (and purport to name) propositions, a kind of abstract entity, and that their proper analysis is by using both DSTs and dot-quotes: that-p = the p. He would not approve of unquoted, un-thated sentences flanking ‘implies’: *”It is raining implies the streets will be wet.” e) Read this way, ‘implies’ is not really a logical connective, since it is not a kind of conditional in the object-language. f) What about quantifiers? There are two reasons to think that they also count as forming statements sabout the real orders: i) They do figure in perspicuous (Bradleyan-regressavoiding) Jumblese, alongside names. Notice that in the definitive “Naming and Saying” version of Jumblese, which includes rules for translating PM-ese into Jumblese, nothing is said about how Jumblese handles logical sentential connectives. Presumably, logically compound truth-functions of Jumblese sentences are standard displays of those sentences relative to one another. So if “a is red” is a, and “a is square” is a, one might write “a is red or a is square” as aa. Conjunction might be: aa. ii) If quantification is handled substitutionally, then universal quantification is a special kind of conjunction, and particular quantification is a kind of disjunction. (We know from Belnap’s and Kripke’s work that, contra Quine’s claims, the expressive power of substitutional quantification is not less than that of ‘objectual’ quantification. The problem is quantifying over uncountable collections, e.g. the real numbers, in a language that only has a countable number of singular terms. The solution is, in effect, in the metalanguage to quantify over arbitrary extensions of the countable language. In any case, Quine must think there is 2 Document1 Brandom some way to invoke such collections in the metalanguage in which the domain of his models is specified.) As far as I know, WS never says how he thinks about quantifiers. 4. Here is the next passage: The idea that acts of sense are informed by not as well as by white, by implies as well as triangular is rooted in the fact that whiteness is what it is by virtue of belonging to a family of competing qualities (what is white is ipso facto not red) and that triangularity is what it is by virtue of implying trilaterality. Thus if the mental words white and triangular are in the act of sense so also must be not and implies. The alternative I am recommending is to say that none of these words are present in the act of sense, for it does not belong to the intentional order. To which it can be added that the predicative word white doesn’t make sense apart from statement; white and triangular thing presupposes (this) thing is triangular. Predicates cannot be in sense unless judgment is there also. [BBK—217-8] a) The ‘thus’ seems hard to justify: why couldn’t the material incompatibilities and consequences be ‘in’ sense, but the vocabulary needed to make them explicit not be? Sellars does seem to claim (not only here), with McDowell, that non-logical vocabulary cannot intelligibly be taken to be deployed unless logical vocabulary also is actually deployed. But why could it not be (as I claim in BSD) that this is not so, and that the temptation to think it is stems from a hasty and sloppy way of putting the correct point that in deploying non-logical vocabulary one already knows how to do everything one needs to know how to do in order to deploy logical vocabulary, if it were introduced into the language. “Grasp of a concept is mastery of the use of a word,” and one might not yet have the word. Without it, one is in no position to entertain logically complex thoughts: to wonder whether p(qp), for instance, or whether (p~p)~(p~p). This issue goes back already to Kant and Hegel, who insist that one must actually deploy the pure, categorical concepts, in order to deploy any ground-level concepts. b) Even if none of these words is in sense (and that seems right: they are governed by norms in a way that the properties—even analogical properties—of sense are not), is it not still the case that the properties triangularity and trilaterality are what they are in (partly) virtue of the material consequence relations between them, and triangularity and circularity are what they are (partly) in virtue of the material incompatibility relations between them? WS agrees, but thinks these properties are not items in “the real order”. Statements apparently about them are disguised (covert) metalinguistic statements about words. This is where I (and Hegel according to me) see modal relations of material (nonlogical) consequence (“mediation”) and incompatibility (“determinate negation”) as normatively governing (serving as a standard of correctness for) normative relations among discursive items (which would be described in metalinguistic terms). Sellars, I think, sees the same situation, but his strategy for articulating it is to treat the modal relations as therefore covertly metalinguistic. His notion of picturing then tries to capture 3 Document1 Brandom the relations, in effect, between normatively articulated discursive items and modally (according to me) articulated objective items (“in the real order”). One difference is that he is obliged to see this relation as non-normative, as a matter of matter-of-factual regularities. One question here is then: Must he avoid, and if so can he avoid, and how does he avoid the gerrymandering-disjunctivitis objections that plague regularism (about norms)? c) Better: the relation I see between objective modal material relations of consequenceand-incompatibility and subjective normative material relations of consequence-andincompatibility is just what Sellars is describing (in a two-barreled way) in terms of the two isomorphisms: of picturing and of signification. Those two isomorphisms describe two sides of the one coin that is the relation between objective modal material relations of consequence-and-incompatibility and subjective normative material relations of consequence-and-incompatibility. Picturing represents the relation as an objective modal one—a matter of the dispositions of the systems (he says ‘habitus’ at [222]), while signification represents it in normative, discursive terms. These correspond to causal and normative functionalism, respectively. Sellars’s overall claim is that the picturing isomorphism is a presupposition of the signification isomorphism. [Here one might compare Wittgenstein’s remarks about how agreement in matter-of-factual dispositions to respond to novel cases is a necessary condition of various practices.] 5. Picturing: a) One question here is: What are the termini of the picturing relation? Are they complex objects? Or are they facts? The Tractarian answer (which WS seems to want to endorse in NS) is the latter. Map-facts picture terrain-facts because we can infer terrain-facts from the map-facts. But given that WS thinks facts are not “in the real order”, that apparent reference to them is covertly metalinguistic, he cannot think of picturing like this. For that would require reference not just to the world and the discourse, but to a metalanguage. And he is going to want to say that the metalanguage also pictures the relations between the object language and the world—which requires reference to a metametalanguage. This regress might, I suppose, be construed so as not to be a vicious regress, but it is hard to see how. b) Here is a passage that speaks to the issue: [E]ven though these two isomorphisms are quite distinct and belong to two universes of discourse, there is nevertheless an intimate connection between them which can be put by saying that our willingness to treat the pattern ‘::’ as a symbol which translates into our word ‘lightning’ rests on the fact that we recognize that there is an isomorphism in the real order between the place of the pattern ‘::’ in the functioning of the robot and the place of lightning in its environment. In this sense we can say that isomorphism in the real order between the robot’s electronic system and its environment is a 4 Document1 Brandom presupposition of isomorphism in the order of signification between robotese and the language we speak. [226] Here the language is of the “place of [a sign design] in the functioning of the robot” and the “place of lightning in its environment.” That latter phrase seems ambiguous between thinking of the environment as a complex object of which events of lightning are parts, and thinking of the “place” as a matter of the fact that lightning precedes thunder. c) In ftnt 9 to [222] Sellars says “the ‘language’ of picturing is truth-functional.” d) [A]s the robot moves around the world the record on the tape contains an ever more complete and perfect map of its environment. In other words, the robot comes to contain an increasingly adequate and detailed picture of its environment in a sense of ‘picture’ which is to be explicated in terms of the logic of relations. [222] So one way to ask the question is: How does the “logic of relations” understand isomorphism? I think the answer intended is: a structure-preserving mapping between complex objects, thought of as relational structures. It will always be possible to think of such mappings as supporting inferences from facts about one structure to facts about the other. But that is an optional characterization, and does not seem to be the one WS is after. 6. What, then, of the “isomorphism of signification”? That isomorphism is one of functional discursive role in norm-governed practices. Here what matters is that we can understand ‘::’ as a lightning. 7. Sellars’s conclusion of his “large scale contrast between two theories of the mental word” [228] is: [I]f one confuses picturing with signifying and if one takes signifying to be a relation between a word and a real—to use a simple illustration, if one confuses between tokens of the word ‘man’ picture men (more accurately, are constituents of statements which picture men) and tokens of the word ‘man’ signify men and take the latter to involve a relation between the word ‘man’ and the absolute nature man, then, since both signifying and picturing are isomorphisms, one will think of the actualities which token the word as isomorphic in the Aristotelian sense with the physical actualities which embody the absolute nature man, i.e. individual men. And one will put this by saying that the actualities which token the word embody the absolute nature man— though in a unique way (‘immaterially’). [227] 8. In TLA, the key distinction is that between two concepts of self-presentingness. These are variously characterized as: a) SP1: direct apprehension interpretation [256]; ontological sense [256]; “that for an expanse of blue (a sensing bluely) to be self-presenting is for it to be available for a logically distinct act of direct apprehension (i.e., an apprehension of it as a case of blue)” [256] 5 Document1 Brandom b) SP2: belief interpretation [256]; epistemic sense [256]; “that for it to be self-presenting is for it to be available for a logically distinct act of believing it to be a case of blue.” [256] 6 Document1