Brown Curley Howser IEO Paper

advertisement

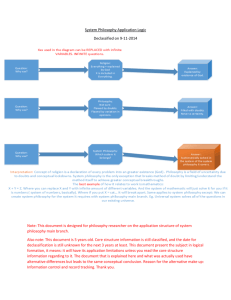

Running head: GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY Graduate Women in Philosophy: An I-E-O Model to Increase Women Faculty Members in Philosophy Elizabeth Brown, Katherine Curley & Dylan Howser The Pennsylvania State University 1 GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 2 Graduate Women in Philosophy: An I-E-O Model to Increase Women Faculty Members in Philosophy Introduction This summer, a star male faculty member, Colin McGinn at the University of Miami resigned in response to sexual harassment allegations and, as The New York Times reported, “a debate over sexism is set off” (Schuessler, 2013). Although the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) fields have gained significant attention surrounding the unequal representation of women in the field, women in philosophy are just recently entering the conversation. The percentage of women full-time philosophy professors in 2000 was only 21.9 percent (Division APAP, 2011). The estimated percentage of women in STEM is 27 percent (Kaminski & Geisler, 2012). Not being a gender-specific field, the unequal representation of women in philosophy appears significant. Even popular culture has taken an interest in the issue. One look at the selection of articles tagged “women in philosophy” in Stone, The New York Times’ philosophy blog, leads the reader to endless articles also tagged “discrimination” and “sexual harassment.” Many of the articles talk about the lack of diversity and respect towards women in the field. Furthermore, in 2010, an entire blog was started to anonymously report instances of sexual harassment in philosophy departments (What is it like to be a women in philosophy?, 2013). Once an entirely male-dominated field, philosophy is still developing and defining the pipeline for women to attain tenured faculty status. Today, philosophy remains as one of the most male-dominated disciplines in the humanities, and highly skilled women exit at all stages of the pipeline (Norlock, 2009). The conversation has recently begun and the inputs and environments fostering persistence in the field are newly being explored and researched. In an effort to explore the GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 3 different factors leading up to getting a full-time faculty position, we will use Astin’s InputsEnvironments-Outputs (I-E-O) model (Astin, 1970a, 1970b, 1991) as a framework to explore the outcome of attaining a full-time faculty position in philosophy as a woman. First, we will explore the different components of what incoming students bring with them that contributes to persistence. Then, in order to analyze the environmental factors that encourage and discourage women to pursue a full-time faculty position, we describe and break down the different components in a graduate philosophy program that influence this decision. Lastly in the model, we will articulate the model’s desired outcomes. The proposed model is developed through a series of interviews with current faculty and graduate students in philosophy and thorough research on women in philosophy, drawing some parallels with the body of research regarding women in STEM and other I-E-O models used in higher education. This model attempts to synthesize the current research regarding the persistence of underrepresented groups in majoritydominated fields and explore how we can support more women to get involved in philosophy and succeed. Finally, we will discuss the research and how the model contributes to the current discussions surrounding women in philosophy. The Model In this paper, we discuss an original I-E-O model designed to help current philosophers, academic and student affairs administrators, and other interested parties better understand the challenges faced by graduate women in philosophy as they progress through their journey to earn PhD’s in philosophy and secure full-time, tenure-track positions in philosophy. Although the terms have very different definitions, in our paper, persistence and attainment of faculty position can be used interchangeably. We see persistence as a prerequisite of faculty attainment and GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 4 faculty attainment as the final accumulation of the persistence in philosophical study. The full model with this outcome that will be discussed in this paper can be seen in Figure 1. Figure 1. I-E-O Model for Graduate Women in Philosophy. This model illustrates the I-E-O model for graduate women in philosophy that we discuss throughout this paper. Inputs The first part of the I-E-O model is inputs. The inputs are divided into four categories: prior education experience, internal characteristics, family background and demographics, and admission and institutional choice. Prior Education Experience The first and most formative input contributing to the decision of getting a PhD with the intention of gaining a full-time faculty position is prior education experience. Research shows that the biggest drop in the pipeline for women persisting in philosophy is from introductory GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 5 philosophy classes to a philosophy major or minor in undergraduate (Calhoun, 2009; Paxton, Figdor, & Tiberius, 2012). Therefore, the quality of the first intro class in one’s undergraduate institution – or even high school – is crucial to further persistence. Not mentioned in the research, but brought up as an important factor in each interview we conducted, is the existence of diverse classes and positive role models (anonymous graduate student, personal communication, November 1, 2013; C. Griffin, personal communication, November 4, 2013; D. Valentine, personal communication, October 30, 2013). In a related field, the existence of role models in one’s undergraduate has been seen to increase persistence of women in STEM (Mason, 2009). In this research and the interviews, having role models that are at least either similar to the student demographically or teach the field of study the student is interested in during one’s undergraduate demonstrates influence on further persistence and motivation to stay in philosophy. Finally, taken from Weidman’s (1989) study on undergraduate socialization, research suggests a certain level of aptitude and pre-professional preparation needed to succeed in graduate school. All of the students interviewed had extensive exposure with philosophy in undergraduate and self-reported that they were well prepared for the graduate level classes (anonymous graduate student, personal communication, November 1, 2013; C. Griffin, personal communication, November 4, 2013; D. Valentine, personal communication, October 30, 2013). One graduate student, for example, uses her undergraduate experience as the model for which she hopes to emulate in the future (C. Griffin, personal communication, November 4, 2013). By experiencing the seminar style philosophy classes as a student, Griffin felt apt and determined to emulate this quality of discussion where everyone has a voice again. GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 6 Taken together, this characteristic of prior education experience can be described by: quality of first philosophy class, existence of positive role models, and one’s aptitude. Internal Characteristics Outside of these more external experiences, inputs into the graduate experience also include internal and personal characteristics. Recently, the most influential work in the field discusses the inability for many students to develop compatible schemas surrounding both “philosopher” and “woman” so that they coalesce (Haslinger, 2008). While these can be further developed in graduate school, initial schemas need to be at least overlapping enough to envision them attaining a PhD in the first place. Each current graduate student interviewed mentioned that sorting out their identity as it related to philosophy was an important part of the process even prior to graduate school. One student said, “I am not so tied to the field or the institution, but what it can help me do” (D. Valentine, personal communication, October 30, 2013). Being able to dissociate herself from field, Valentine is able to cope with the components of the environment that are hostile or that she does not like. By doing this, she has the internal capability of self-selecting her environment and ignoring any discouraging factors. Similarly, but with a different conclusion, another student said, “Philosophy is the best venue to work on change and be a product of that change…I have defined myself by this.” (Anonymous graduate student, personal communication, November 1, 2013). This graduate student coped in a very different way, but is still able to see herself congruent to the field because it is so ingrained in her self-definition. The last graduate student we interviewed had a similar experience. Due to her very positive undergraduate experience in philosophy, Griffin states, “I try to recreate the environment of St. John’s and have faith that things can be better” (C. Griffin, personal GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 7 communication, November 4, 2013). More than just seeing oneself in the field, Griffin and the anonymous graduate student both are committed and motivated to be change agents within the field. This ability to envision oneself in the field, thus, encapsulates the pre-college inputs of commitment, motivation, and goals taken from Tinto’s (2012) retention model and also aspirations, values, and career goals taken from Weidman’s (1989) model of undergraduate socialization. In order to persist, students must have the internal commitment, motivation, and goals to be a tenured track professor which requires the clear ability to envision this same achievement. Family Background and Demographics Another personal characteristic that appears to affect the graduate experience and future outcomes is family background and demographics. Women of color, for example were totaled at zero due to insufficient data in the latest census of full-time philosophy faculty professors in 2003 (U.S. Department of Education, 2011). People of color have been found to face added barriers in philosophy such as combating stereotypes and implicit race biases (Armodio & Devine, 2006; Pearson, Dovidio, & Gaertner, 2009). While race has been most heavily studied and seen as a compounding factor in retention, other issues such as class and nationality also play a role according to a current anonymous graduate student applying for tenure-track faculty positions (personal communication, November 1, 2013). This is consistent with research on undergraduate socialization by Weidman (1989) which includes socioeconomic status as an important pre-college characteristic. Family background and demographics certainly are important inputs, but more research needs to be done to explore the breakdown of this category, particularly with women in philosophy. In general, though, family background including socio- GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 8 economic status, ethnicity, and race has been proven to have significant impact on admission, retention, and college choice (Tinto, 2012). Admission and Institutional Choice Once a student decides to attend further schooling, another added barrier is getting in. Studies show that reviewers favor men over women in assessing randomly assigned gender resumes (see for example Cole, Field, & Giles, 2004; Schmader, Whitehead, & Wysocki, 2007; Steinpreis, Anders, & Ritzke, 1999) and professors who write recommendation letters are more likely to write more positive letters to males than females (see for example Moss-Racusin, Dovidio, Brescoll, Graham, & Handelsman, 2012). Many admissions processes are not doubleblind meaning which has been seen to have a negative impact on female admissions (see for example Budden et al., 2008). Simply getting into a philosophy program even after expressing the desire to become a full-time faculty member is challenging. In choosing which school to attend and apply, both the curriculum and commitment to gender equity varies. The percentages of women in tenured faculty positions range from fifty percent to zero percent in Philosophy PhD departments around the country (Van Camp, 2011). Furthermore, what each institution’s conception of what is an acceptable field of study in philosophy varies. According to a current philosophy PhD student, there are two general categories of study in philosophy: the traditional Western canon and everything that critiques this (D. Valentine, personal communication, October 30, 2013). Certain programs sell and value one category over the other and tend to sell particular areas of study in their department for incoming students. These foster certain expectations going into one’s chosen institution and the weight you place on each shapes these same expectations—for example, Valentine said she asked herself when applying: “is gender of the faculty important or not?” (D. Valentine, personal GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 9 communication, October 30, 2013). The particular weight and expectations students have of the institutions, therefore, are additional components of the inputs students bring into their future philosophy studies. More research needs to be done on if and how faculty demographics and the existence of role models influence institutional choice for studying philosophy in particular. For our model, admissions barriers and expectations surrounding institutional choice are included in the inputs for women’s persistence in philosophy. Environment The second part of the I-E-O model is environment. Our analysis examines four aspects of the environment for graduate women in philosophy: classroom experiences, sexual harassment, implicit bias and stereotype threat, and perceived support. No matter the field of study, graduate education experiences typically boast a wide variety of factors that influence a student’s interest in persisting in a particular program and in pursuing a specific type of career. As we continue in our analysis of graduate women students as they move toward or away from a full-time faculty career, we will analyze elements of the environment that women students are experiencing during graduate school. Research indicates that women in philosophy programs are experiencing many factors differently than their male peers. This section will explore some of the major environmental factors influencing graduate women and young professionals as they consider a future career as a faculty member. Throughout our inquiry, we found that there is a serious lack of research on the graduate school experiences of women in philosophy (and even women in general). However, we found many ideas circulating online throughout the blogosphere and promises of forthcoming research on the topic. Through our research we also discovered many similarities in the environmental factors women experience in STEM fields. Much of this section will focus on the negative influences graduate women in philosophy face as they contemplate a career in academia. As we GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 10 will note throughout this section, current philosophers (women and men alike) and prominent professional organizations in the field are taking note of these issues and are proactively acting to reduce these harms and negative experiences for future members of the philosophy community. Classroom Experiences The classroom experiences of graduate women in philosophy can be daunting. As discussed above, the classroom experiences of undergraduate women interested in pursuing philosophy influence their decision whether or not to pursue a philosophy major. Similarly – in graduate school – women in philosophy are influenced by the predominately male learning environment. Graduate classroom experiences play a powerful role in attracting or deterring women in careers as faculty members, as teaching is a significant component of the faculty experience. As is the case with other types of minority students in majority-dominated environments, these women can experience feelings of academic and personal isolation as well as stereotype threat, as articulated by numerous women on the popular philosophy blog for graduate and young professionals, What is it like to be a woman in philosophy? (2013). In her research, Anne Wilson Shaef (as cited in Rypisi, Malcom, & Kim, 2009) argues that women live and operate in a “White Male System” that permeates educational environments for women. Shaef concludes that women in underrepresented fields, like STEM or philosophy, are not valued as worthy professionals because of the “logical” and “all-knowing” dominant system (Rypisi et al., 2009). Similar phenomena regarding gender equity in the classroom were recently studied at Harvard Business School. The year-long effort and accompanying study found that by making small changes in how they run their classes, faculty members can actually make the classroom environment more welcoming to women students (Kantor, 2013). Those parties interested in GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 11 increasing the academic learning environment for graduate women in philosophy should seriously examine the body of research regarding women in STEM as well as the recent case study at Harvard Business School for effective strategies. Sexual Harassment As indicated by the example we mention in the introduction of this paper, sexual harassment in philosophy is a problem that is receiving more press, attention, and credit for the challenge of recruiting and retaining women in the field. Sexual harassment is an important piece of the environment to consider when examining why more women are not equally represented in the field of philosophy, as research has shown that incidents of sexual harassment and a culture perceived to be conducive to sexual harassment can lead to decreased educational persistence on college and university campuses (Hill and Silvia, 2006). The recent resignation of high-profile philosopher Colin McGinn at the University of Miami in response to sexual harassment allegations is one of many stories that are drawing attention from the philosophy community as well as the greater community within academia and beyond (Schuessler, 2013). While it is difficult to get data that accurately represents the prevalence of sexual harassment in the realm of philosophy academe, there are cues that seem to indicate that it is a significant issue. First, the online blogosphere for women in philosophy is ripe with anonymous, personal stories of sexual harassment (Saul, 2012; Saul, 2013). The popular blog What is it like to be a woman in philosophy? (2013) features a collection of numerous vignettes of women graduate students and faculty members who have experienced some form(s) of sexual harassment. The ability to post anonymously without fear for one’s academic career or professional reputation is certainly appealing, and women are taking advantage of the ability to build an online, supportive community with others who share similar experiences in the field. GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 12 The recent case involving McGinn sparked a fury of online debate, raising important questions about the actions being taken to support victims of sexual harassment. In the time since the McGinn story broke, several women graduate students in philosophy have considered filing complaints and have contacted sympathetic faculty members – even those at other institutions – as well as the American Philosophical Association’s Committee on the Status of Women (Schuessler, 2013). Recently, the APA appointed a new ad hoc committee to further investigate sexual harassment in the discipline (American Philosophical Association, 2013). In a March 2013 interview published online, the committee’s chairwoman stated that she felt it was important for the philosophy community to address issues of sexual harassment as a discipline because she believes that “the effects of harassment piggyback on the effects of a lot of other marginalizations that are evident in philosophy” (Kukla, 2013). The chairwoman’s quotation indicates that there is a connection between sexual harassment and the more broadly based issues of marginalization in the field (Hill & Silva, 2006). As the ad hoc committee begins the necessary work investigating strategies to eliminate sexual harassment in the field, it will be interesting to observe how these issues and strategies are connected (if at all) to other issues related to marginalization, like implicit bias and stereotype threat, for graduate and professional women in philosophy. Implicit Bias & Stereotype Threat Members of the philosophy community who are concerned with the representation of women in the field are also discussing ways in which the classroom and out of the classroom experiences are harmful to graduate women in philosophy, specifically the issues of implicit bias and stereotype threat. Implicit bias is the idea that people unconsciously hold negative ideas and associations about particular groups of others in a way that influences their behavior toward a GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 13 person or group of people (Roberts, 2011). In philosophy, this implicit bias could root from a perceived lack of women philosophers in history and a lack of women currently doing work (and thus “proving” that they are capable) in the field. In her blog, Saul (2012) discusses the very real possibility that implicit bias is a contributing factor to the chilly climate that women experience throughout graduate school and as faculty members in the field. Moreover, as discussed above, implicit bias could even be playing a role in harming women’s chances of securing faculty positions after graduation. Researchers, including Hall and Sandler (as cited in Rypisi et al., 2009) have confirmed that implicit bias contributes to a chilly climate which “discourages female students from participating in class, dampens career aspirations, [and] undermines their self-confidence,” all of which can deter women from pursuing particular academic or professional paths with sexist overtones (Rypisi et al., 2009, p. 122). While the lack of philosophy-specific data in this area of study makes it difficult to confirm, the wealth of anecdotal stories learned from our interviews and online research seem to indicate that this phenomenon is regularly occurring in philosophy graduate programs. Similarly, women graduate students as well as professionals in philosophy are likely to experience stereotype threat. Stereotype threat refers to feelings of risk of confirming a negative stereotype about an identity group that can inhibit one’s ability to perform well at a particular task or in a specific situation (Steele & Aronson, 1995). Moreover, research has shown that environments where individuals experience repeated instances of threat and implicit bias can actually lead to disassociation from the environment (Steele & Aronson, 1995; Steele, 1997). In the case of graduate women students in philosophy, this could be a possible explanation as to why there is a pronounced lack of professional women philosophers. Saul (2012) indicates that stereotype threat in women in philosophy can be regularly triggered by a variety of factors, GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 14 including feelings of isolation in the classroom, overwhelmingly male authors on semester reading lists, predominately male faculty members, and national conferences regularly featuring only male keynote speakers. Stereotype threat can negatively influence the performance abilities of the threatened population in academia, such as women in STEM or – in this case – women in philosophy (Rypisi et al., 2009). The issues of implicit bias and stereotype threat with respect to women in philosophy have continued to gain traction recently, and there are currently significant efforts from individuals and organizations to combat these issues in the field of philosophy. Saul, one of the earliest voices to draw attention to these issues in the field, is authoring and co-authoring a number of articles and books on the topic (Saul, 2012). Moreover, long-standing organizations like the American Philosophical Association (APA) and newer groups like the Implicit Bias and Philosophy Research Network and various international branches of the Society for Women in Philosophy (SWIP) are beginning to devote significant time, research attention, and action to marginalization issues like implicit bias and stereotype threat. Perceived Support Another major influence on women considering a career as a philosophy faculty member is the support they perceive from others. Professional associations play a significant role in shaping the academic and professional environment of the field. The APA Committee on the Status of Women was founded in 1993 to support women in philosophy and it plays a significant role in helping younger women who are new to the field identify professional resources and role models (American Philosophical Association, 2013). For instance, each month the Committee’s website features a bio and the research of a woman philosopher in an effort to inspire and GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 15 promote community. These efforts to increase the number of visible women philosophers will also help identify role models in the field for women and other underrepresented groups. The importance of academic and professional mentors who are women in the field of philosophy should not be overlooked. In the similar arena of STEM fields, Belenky et al.’s (1986) research has shown that the lack of women role models can exacerbate gender-biased treatment and feelings of isolation. More recent research specific to the field of philosophy indicates that mentoring women graduate students and young professional philosophers in academia is a critical piece of understanding the persistence of women in the field (Antony & Cudd, 2012). As we have indirectly illustrated throughout this paper, online communities created through blogs can have a major influence on how students experience their own graduate education or professional career. As today’s students are more comfortable engaging with others in an online setting (Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, 2007), online interactions between other women students and professionals in the field can provide students with the social communities and integration that Tinto (2012) describe as essential to educational persistence. While women philosophers may feel isolated on their own campuses, the active and vibrant online community provides a valuable opportunity to connect with others facing similar challenges in the field. Moreover, some of these online communities are translating into physical action that has a direct influence on the environment of the field for women. For example, a few years ago the Feminist Philosophers blog launched the Gendered Conference Campaign. This campaign is a project that tracks all-male conference lineups and explores the harms to women philosophers and the greater community while “drawing attention to this systemic phenomenon” (Feminist Philosophers, 2009). From this example and the others provided throughout this paper, it seems that these types GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 16 of online grassroots efforts seem to hold the most promise in mobilizing the academic community of philosophy to become more welcoming to women and other minority groups. External Influences Larger societal and other external influences can also affect a woman’s ability to succeed as a graduate student in philosophy. While not the central focus of the model we present in this paper, we recognize that a wide variety of external factors can influence choices related to a woman’s decision to enter and persist in a graduate philosophy program. Examples of these external factors include the perceived or projected job market in the field, support (or lack thereof) from family and friends, or serious illness of a spouse or partner. Outcomes As both the incomes and environment section show, women in philosophy have a tough road to travel in their academic career. Sally Haslanger, a philosopher at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, argues “as recently as 2010, philosophy had a lower percentage of women doctorates than math, chemistry, and economics” and this shows in the number of women faculty members in highly ranked philosophy programs: 21.9 percent (Haslanger, 2008; 2013). In opinion pieces published in the New York Times after the resignation of Colin McGinn, five women philosophers give their perspective on what it means to be a woman in philosophy. Much like the environment women go through during their graduate program, professional philosophers go through the same challenges: lack of mentorship, sexual harassment, stereotyping, and other exclusionary practices (Haslanger, 2013; Alcoff, 2013; Langton, 2013; Antony, 2013; O’Conner, 2013). It is important for all members of the philosophy community work to solving these challenges, since as Peg O’Conner (2013) notes, GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 17 Women can only do so much. We can teach and mentor well, open doors when we have some institutional power, advocate for change in admission and harassment policies, for example. But nothing will change unless and until more of our male colleagues begin to use their male privilege in very different way. In this section we will explore the necessary outcome of gaining tenure-track positions, but look at the possible post-graduate school barriers towards achieving this goal. We will look at the barriers presented to women philosophers in researching, teaching, and providing service to the philosophy community: all important aspects of the tenure process. Our specific outcome is to raise the level of tenure-track women philosophers in colleges and universities. It is important to note the difference between tenure-track and adjunct positions. Tenure-track positions are more prestigious, secure, and include health benefits. Typically these are professors you think about when you hear the word professor. However, more research is coming out on the role adjunct professors have in higher education. Adjunct professors are contract employees that teach courses at a much lower rate than tenured or tenure-track professors. They also rarely receive any benefits. The recent death of Margaret Mary Vojtko has becoming a tipping point for the consideration of adjunct pay and benefits. Vojtko died in debt and without health care after nearly 25 years of teaching French at Duquesne University (Ellis, September 9, 2013). While it is important to further discuss the difference between tenured and adjunct professors, we only note the difference to show the discrepancy between the two tracks. It is also important to note that most of the statistics used by women philosophers on the subject of employment only use statistics of tenured and tenure-track professors. This means that the knowledge of the number of women adjunct professors and their working conditions are almost non-existent. GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 18 The research shows that women and minorities are excluded from professional philosophy. As noted earlier, only 21.9 percent of the employed philosophers are women. It is even more shocking that less than 30 of the 11,000 American philosophers (both adjunct and tenure-track) are black women. Much of this has to do with the pipeline issues described in earlier sections, but it is also an issue with the environment. Haslanger (2008) muses, “Women, I believe, want a good working environment with mutual respect. And philosophy, mostly, doesn’t offer that” (pg. 212). The most notable examples of this are the gender dichotomy of philosophy and ideals of philosophy: “rational/emotional, objective/subjective, mind/body… penetrating, seminal, and rigorous…” (Haslanger, 2008, p. 213). Collectively, academic philosophy is framed as very masculine and this contributes to the tenure process. Barriers Several barriers surround professional women philosophers as they work through the tenure-track process that keeps them from securing tenure or tenure-track positions. The first, and biggest, barrier women philosophers have to overcome in their journey to tenure is research – the largest factor in most tenure-track positions. In the seven most prominent philosophy journals only 12.8 percent of articles were written by women from 2002-2007. Since then the figure has only increased to 13.5 percent (Haslinger, 2008). If being published in journals is one of the major factors to getting tenure, then philosophy is not doing a great job of closing the gap. Haslanger (2008) also hypothesizes that women philosophers are not being considered as strongly by reviewers, which would lead to underrepresentation. It can also be speculated that feminine philosophical interests, e.g. feminism, are less likely to get publication, so women philosophers are forced into different areas of interests. Women on the Wordpress, What is it like to be a woman philosopher?(2013), often report being forced into different areas of interest in GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 19 order to fit the woman philosopher mold. For example, one of the authors was challenged during their senior philosophy thesis when they wanted to write on the philosophy of love. Since it did not fit the current mold of philosophy, their professor asked if it would be philosophical enough for a senior thesis. While this may be an undergraduate example, Kristie Dotson (2011) contemplates the question, how is your project philosophy? It seems anything outside of the canon of Western philosophy is taken less seriously, and it seems more women and minorities are interested in areas outside of it. Therefore, women philosophers have a harder time fulfilling the research aspect of tenure. Next, teaching can also act as a barrier for women philosophers. Much like in research, women philosophers are often expected to teach certain subject areas even if they are not experts in that subject, e.g. feminist philosophy and the history of philosophy. Also, with the lack of women philosophy graduate students, women philosophy professors may not have enough interest in their subject areas to be able to teach a course on the subject. bell hooks (1994) argues that women professors in general have an issue with male students. In an academic field with more men than women, it may be difficult for women philosophers to feel confident in the classroom. As Haslanger (2008) notes on being solo status, being a woman professor in a largely masculine classroom could make one “feeling tongue-tied and stupid” even when otherwise they would confident and collected (p. 218). Also, this could affect their course evaluations and their results could be different than their actual performance (hooks, 1994). Collectively, this could lead to barriers in teaching for women philosophers. Finally, service to the university and philosophical community can be hindered by their gender. As Jacqui Poltera (2011) writes, “Philosophy is cutthroat and ruthless” (p. 423). This affects a woman’s ability to move up in the university and philosophical communities. Whether GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 20 it is serving on different campus committees or professional committees, service to the university takes away from a woman philosopher’s time in other areas, i.e. researching and teaching. For example, Poltera (2011) notes that senior women philosophers are often seen as de facto mentors for junior women philosophers, but this is a mistake to make this presumption. If the senior women philosophers have a rough time making strides in their community, this could push the women students away from the profession. Mentoring also takes a lot of time and effort, which takes away time from research and teaching. Therefore, service to their community can be difficult when research is stressed so much and women philosophers are used to teach general philosophy courses. The most startling image to compare the outcome of tenure-track positions for women philosophers is Dotson’s (2011) concrete flower analogy. Whether it is through the barriers described earlier in this paper, throughout this section, or ones we did not touch, women entering into professional philosophy can be seen as flowers sprouting through concrete. While “[t]hey give the impression of being strong, survivors… On closer inspection, however, many concrete flowers are fragile and clearly starved for basic nutrients” (pg. 408). If we want to improve the amount of women in philosophy that eventually obtain tenure-track positions, we should start with breaking through the concrete (i.e. barriers) to having a healthy and thriving career in philosophy. Discussion This model is designed to explore why there is a lack of full-time faculty members that are women. The ongoing conversation happening online jumpstarted the discussion, but through our research we find that much more research needs to be done. Our goal is that this research will help define a pipeline for women entering philosophy. Due to the research we found on GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 21 women in predominately male fields of study, particularly in STEM, we believe the model to be highly generalizable to academic fields that share similar demographics. Which Comes First: The Professors or the Students? As noted earlier, the largest leak in the pipeline of securing more tenure-track women philosophers is the enrollment of women in philosophy classes after their introductory course. It has also been noted that the there is a lack of professional women philosophers, and retention in academics fields is bolstered by working with academics that look like you. However, there cannot be more women philosophers if the pipeline continues to leak them. Therefore, should we put our attention on women philosophy students or professional women philosophers? In order to best increase the amount of professional women philosophers we believe that attention should be focused on both students and professors. Solely focusing on students would possibly produce more women philosophy graduate students and Ph.D. holding women, but without institutional support for professional women philosophers than there would be a bottleneck in the amount of jobs for which they could apply. If we solely focused on professors, then we would not be providing enough resources to get women students involved in philosophy. It was also noted above that more women philosophers may not be the answer since some may not be the best role models for women philosophy students. However, some may argue for a trickledown effect, similar to trickledown economics, but this would depend on a large number of factors, i.e. the environment. By focusing on both students and faculty, we could adequately provide resources to both parties and create lines of communication between those wanting to enter philosophy and already working (or struggling to work) in philosophy. Applicability to Various Student Communities GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 22 Our inspiration for a model explaining the underrepresentation of women in philosophy was largely derived from the numerous models explaining the lack of women in STEM fields. As the body of research regarding the status of women and other underrepresented groups in philosophy continues to grow, more intra-group differences may be observed and explained using adaptations of this model. For instance, women of color may experience their graduate education and professional life in philosophy differently than their white counterparts (Paxton, 2012). Moreover, examining the environment could help to explain the challenges other populations besides women (e.g. men from low socioeconomic backgrounds) face in pursuing full-time faculty positions in philosophy. However, we would suggest that future researchers exercise caution in equalizing the experiences of other underrepresented groups within the field of philosophy and outside of the discipline with those of women in philosophy. Through our research and analysis, we believe that the similarities faced by women across academic disciplines seem to speak to a larger, more comprehensive problem within academia and across society. We hope that future research and efforts by campus professionals is dedicated to determining and implementing interventions to reduce the barriers to persistence for underrepresented groups in philosophy and beyond. Roles of Campus Professionals One of the overarching goals of our model is to define a pipeline for future full-time women faculty to follow and to help faculty, campus leaders, student affairs professionals, and policymakers to better facilitate this process through being aware of the barriers. By knowing the barriers, policymakers can enact policies, such as sexual harassment reporting and termination of offenders, that will better encourage a positive environment for women philosophy graduate makers. GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 23 Knowing how well online communities have fostered support for this population, student affairs professionals can try to foster this community in person by working in conjunction with academic departments to connect support services and groups of other male-dominated fields such as women in STEM. Taking what we know about engaging women in STEM this could suggest several different practical approaches for student affairs practitioners to better engage women in philosophy. Building this community could be done by creating women in philosophy common areas on campus, sponsoring a female scholar in residence program, developing a service-learning component where women teach younger women about philosophy, bringing prominent feminist philosophers to campus, and developing a mentoring program for women undergraduate, graduate, and professional women in philosophy (Rypisi et al., 2009). Women in philosophy can also be better prepared for the barriers by having a more thorough graduate orientation to talk about being a women in male-dominated fields (Rypisi et al., 2009). By understanding the I-E-O pipeline and barriers, women can be more aware of the external influences and maintain their internal locus of control to persist in the field. Finally, student affairs can be specifically helpful developing and implementing assessments based on practitioner knowledge of climate and culture assessments in the field. In doing so, student affairs professionals can inform the department how women are experiencing the field of philosophy and how to better foster positive engagement in the future. Conclusion As the termination of famous philosopher Colin McGinn in the recent sexual misconduct case illustrates, the tide is turning for women in philosophy. However, there is still a long way to go in order to achieve the goal of creating equitable access opportunities to the realm of professional philosophy. Our I-E-O model provides current philosophers, academic and student GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 24 affairs administrators, and other interested parties with a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges and current research related to the goal of increasing tenured women in philosophy. As our model shows, there are many complex issues that exist in order to create a reliable pipeline of women in the field, and it will require more than just philosophers to make the change. Beginning at the undergraduate level, we must work toward building and maintaining interest in philosophy for women students. This means that we may need to look at how we are first introducing philosophy to students and whether we can better accommodate women’s ways of learning and make the classroom environment more welcoming to women. Research also shows that we must do more to ensure equitable access to professional careers in philosophy for other subpopulations, including women of color. Once these underrepresented groups matriculate into graduate programs, we need to focus on creating a welcoming environment for women and other diverse student populations. Due to significant issues like sexual harassment, implicit bias, stereotype threat, and more, women can be perceive a forced decision between their academic passion and personal safety. Even if women are able to secure a tenure-track faculty position in philosophy, they still fact significant challenges in being taken seriously by their predominately male colleagues and in actually attaining tenure. Overall, our model and the relevant research show that women need to be better supported and provided with the tools necessary to overcome barriers and achieve careers as professional philosophers in the realm of academia and beyond. GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 25 References Amodio, D. M. & Devine, P. G. (2006). Stereotyping and evaluation in implicit race bias: Evidence for independent constructs and unique effects on behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(4), 652‐661. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.652 Antony, L. & Cudd A. (2012). The mentoring project. Hypatia, 27 (2), 461-468. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-2001.2012.01267.x Astin, A. (1970a). The methodology of research on college impact (I). Sociology of education, 43, 223-254. doi: 10.1002/aehe.3640030107 Astin, A. (1970b). The methodology of research on college impact (II). Sociology of education, 43, 437-450. doi: 10.1002/aehe.3640030107 Astin, A. (1991). Assessment for excellence: The philosophy and practice of assessment and evaluation in higher education. New York, NY: Macmillan. Budden, A. E., Tregenza, T., Aarssen, L. W., Koricheva, J., Leimu, R., & Lortie, C. J. (2008). Double‐blind review favours increased representation of female authors. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 23(1), 4‐6. Cole, M. S., Field, H. S. & Giles, W. F. (2004). Interaction of recruiter and applicant gender in resume evaluation: A field study. Sex Roles, 51, 597‐608. doi: 10.1007/s11199-004-54691 Division APAP. 2011. Program review report, 2004–2011. Committee E, editor. http://apapacific.org/governance/Program_Review_Report.2004-11.pdf (accessed April 21, 2012). Ellison, N.B., Steinfield, C., Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of ComputerMediated Communication, 12(4), 1143-1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 26 Feminist Philosophers (2009). Gendered conference campaign. Retrieved from http://feministphilosophers.wordpress.com/gendered-conference-campaign/ Haslanger, S. (2008). Changing the ideology and culture of philosophy: Not by reason (alone). Hypatia, 23(2), 210–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-2001.2008.tb01195.x Hill, C. & Silva, E. (2006). Drawing the line: Sexual harassment on campus. American Association of University Women. Retrieved from http://www.aauw.org/files/2013/02/drawing-the-line-sexual-harassment-on-campus.pdf hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. London, UK: Routledge. Kaminski, D. & Geisler, C. (2012). Survival analysis of faculty retention in science and engineering by gender. Science, 335(6070), pp. 864-866. doi: 10.1126/science.1214844 Kantor, J. (2013, September 7). Harvard business school case study: Gender equity. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/08/education/harvardcase-study-gender-equity.html?_r=0 Kukla, R. (2013, March 18). Chatting with Kate Norlock, Chair of the APA Committee on Sexual Harassment. Leiter Reports: A Philosophy Blog. Retrieved from http://leiterreports.typepad.com/blog/2013/03/chatting-with-kate-norlock-chair-of-theapa-committee-on-sexual-harassment-kukla.html Mason, M. A. (2009, March 29). Role models and mentors. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/Role-ModelsMentors/44794 Moss-Racusin, C. A., Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L., Graham, M. J., & Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Early Edition, 1-6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211286109 GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 27 Norlock, K.J. (2009). Love to count: arguments for inaccurately measuring the proportion of philosophers who are women. APA Newsletters on Feminism and Philosophy, 8(2), 6-9. Paxton, M., Figdor, C., & Tiberius, V. (2012). Quantifying the gender gap: An empirical study of the underrepresentation of women in philosophy. Hypatia, 27(4), 949-957. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-2001.2012.01306.x Pearson, A.R., Dovidio, J.F., Gaertner, S.L. (2009). The nature of contemporary prejudice: Insights from aversive racism. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(3), 314‐338. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00183.x Rypisi, C., Malclm, L. E., & Kim, H. S. (2009). Environmental and developmental approaches to supporting women’s success in STEM fields. In Harper, S. R., & Quaye, S. J. (Eds.). Student engagement in higher education: Theoretical perspectives and practical approaches for diverse populations (pp. 117-135). New York, NY: Taylor and Francis. Roberts, H. (December 18, 2011). Implicit bias and social justice. Open Society Foundations. Retrieved from http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/voices/implicit-bias-and-socialjustice Saul, J. (2012, October 16). Women in philosophy. The Philosophers Magazine. Retrieved from http://philosophypress.co.uk/?p=1079 Saul, J. (2013, August 15). Philosophy has a sexual harassment problem. Salon. Retrieved from http://philosophypress.co.uk/?p=1079 Schmader, T., Whitehead, J., & Wysocki, V. H. (2007). A linguistic comparison of letters of recommendation for male and female chemistry and biochemistry job applicants. Sex Roles, 57, 509‐514. doi: 10.1007/s11199-007-9291-4 Schuessler, J. (2013, August 2). A star philosopher falls, and a debate over sexism is set off. The GRADUATE WOMEN IN PHILOSOPHY 28 New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/03/arts/colinmcginn-philosopher-to-leave-his-post.html?_r=0 Steinpreis, R., Anders, K., and Ritzke, D. (1999). The impact of gender on the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: A national empirical study. Sex Roles, 41(7/8), 509-528. doi: 10.1023/A:1018839203698 Steele, C.M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52(6), 613-621. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.52.6.613 Steele, C.M. & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 797-811. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.797 Tinto, V. (2012). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2011). Table 270: Study of postsecondary faculty. Digest of Education Statistics, 2011. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d11/tables/dt11_270.asp Van Camp, J. (2011). Tenured/tenure-track faculty women at 98 U.S. doctoral programs in philosophy. Retrieved from http://www.csulb.edu/~jvancamp/doctoral_2004.html Weidman, J. (1989). Undergraduate socialization: A conceptual approach. In J. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 5, pp.289-322). New York, NY: Agathon. What is it like to be a woman in philosophy?. (2013). Retrieved from http://beingawomaninphilosophy.wordpress.com/