Describing Culture-Based Interventions

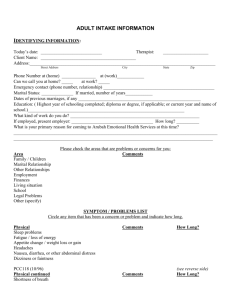

advertisement