Introduction to cinema terminology and writing about film

advertisement

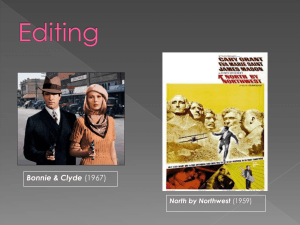

Introduction to cinema terminology and writing about film There are numerous introductory guides to film studies and writing about film. Probably the most useful in terms of understanding ‘technical’ vocabulary and applying it to film analysis is: David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson, Film Art: An Introduction (New York: McGraw-Hill, numerous editions, most recent published 2012). You may also find it useful to look at: Susan Hayward, Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (London: Routledge, most recent edition 2013). Phil Powrie and Keith Reader, French Cinema: A Student’s Guide (London: Arnold, 2002). If you’re interested in looking at something in French, you could try: Jacques Aumont and Michel Marie, L’Analyse des films (Paris: Nathan, 1989). The basic unit of a film is the shot (French: le plan). A shot is essentially what happens between two edits. When writing about film, it is important to be able to talk specifically about individual shots and groups of shots (sequences; French: séquences). In addition to the narrative and dialogue content of a shot (i.e. what happens and what people say), it is important to think about the following things: What a shot looks like (mise-en-scène); How it is filmed (camerawork); How it is connected to other shots (editing); What it sounds like (sound). Mise-en-scène ‘Mise-en-scène’ comes from a French theatrical term meaning ‘staging’. Traditionally it indicates the way in which a given scene is physically organized in space (e.g. the disposition of actors, sets, props, and so on). In French, the term ‘mise en scène’ is often used synonymously with ‘direction’ (e.g. ‘Un film réalisé par Jean Renoir’ is the same as ‘Mise en scène de Jean Renoir’). In English, however, ‘mise-en-scène’ has become a catch-all term to refer to the look of a film. One simple way to think about it is that mise-en-scène designates everything that is placed in front of the camera on a film set. Mise-en-scène therefore includes: sets (le décor); costumes (les costumes); props (les objets de cinéma); lighting (lumière/éclairage); make-up (le maquillage); and the appearance and movement of actors. Mise-en-scène can convey important information about narrative and character, but it also plays a vital role in generating the overall atmosphere and style of a film. Mise-en-scène does not include: camerawork, editing, or sound. Camerawork (Le travail de la caméra). For any given shot, it is worth thinking about how the camera is positioned in relation to what is being filmed, and why. First, it is important to consider framing (le cadrage). Why have the filmmakers chosen to put the camera where it is so that certain things are visible and others are not? How much importance should be ascribed to off-screen space (le horschamp), and why? In thinking about camera work, consider: Distance: how close is the camera to what it is filming, and why? Is it in close-up (gros plan; e.g. head-and-shoulders only) or extreme close-up (très gros plan; e.g. part of a face), typically used for intimate exchanges? The majority of shots in most films are medium shots (plan moyen), which frame people from the waist or knees up. Long shots (plan large), which show a whole person or landscape are often used for setting the scene at the beginning of a sequence. Angle: most shots are filmed more or less from a person’s eye-level; however, some shots use more extreme angles to generate effects of disorientation, intimidation, vertigo, etc. A high-angle shot (plongée) is taken from high up, looking down on something. A low-angle shot (contre-plongée) is taken from low down, looking up at something. Movement: the camera will often move, usually, but not always, in order to follow the action. There are various different types of camera movement: Pan (panoramique): when the camera remains in the same place but turns left or right to look at something. Tracking shot (travelling): when the whole camera is mounted on rails and moves alongside the action (a similar effect can be achieved by placing the camera in a moving vehicle). A camera can track sideways (travelling latéral), forward (travelling avant) or backwards (travelling arrière). Tilt, or vertical pan (panoramique vertical): the camera remains in place but tilts up or down to look at something. Crane shot (plan-grue): the whole camera is mounted on a crane in order to lift it up to look at something from above. Zoom (zoom): the camera does not move but the image is magnified. Hand-held camera (caméra-à-main): the camera is held on the operator’s shoulder (or literally in the hand, if it is a very small camera) instead of on a tripod or other stand. This type of camerawork is associated with low-budget cinema and often gives a shaky effect to the image. This is sometimes exploited, even in big-budget films, to give a sense of urgency, especially in action sequences. Editing (le montage) Editing describes the ways in which shots are joined together. There are several different types of edit: The cut (coupe) is the simplest type of edit, where one shot just switches suddenly to a different one. This accounts for the vast majority of edits in the cinema. The fade (fondu au noir) typically signals a relatively significant passage of time and often marks the end of a sequence. Here the image fades to black for a second or two before fading in on the next shot. The dissolve (fondu) is somewhere between a cut and a fade. Here, the end of one shot is briefly superimposed with the beginning of the next so that, for a moment, both images are visible. This often signals a relatively long gap in time, but not as long as a fade. It is also often used to suggest a relationship between people, places or times. Sometimes several shots in a row dissolve into one another to suggest the slow passage of time or a gradual process unfolding; this is known as a lap dissolve (fondu enchaîné). When thinking about editing, it is also useful to consider the duration (durée) of shots. Shots can last for anything from a fraction of a second to several minutes. It is always worth thinking about why the filmmakers have chosen to start and stop a shot at the moment they have (i.e. why does the shot last as long as it does, and why do the filmmakers cut when they do?). Editing is crucial in giving a film its rhythm: if several very short shots are edited together, the film will appear to be fast-paced, whereas if the shots are much longer, the film will typically come across as slower and more reflective (however, this also depends on what is happening in the shots!). There are several unwritten rules about editing which have been codified over decades of filmmaking. The majority of commercial feature films follow these rules which are designed to help the spectator follow the logic of the story without become lost or disoriented. Together, these rules constitute what has become known as the system of classical continuity editing. It would be worth reading a little about this form of editing and having a general sense of how it works, if only in order to recognize departures from the norm. As a general rule, if you suddenly find yourself confused by a film, it may be because it has departed from classical continuity editing and it would be a good idea to think about how and why the film has done this. Sound (le son) There are essentially three important types of sound in cinema: Speech, whether dialogue or voiceover (voix-off), which is when you hear someone’s voice but don’t actually see them speak; Sound effects (bruitages); And music. For all these sounds, but especially music, it is useful to think about whether the sound is diegetic or non-diegetic (diégétique ou non-diégétique). Diegetic sound has a visible (or at least credible) source within the story-space of the film e.g. a radio, a street musician or a band playing in a club. Non-diegetic sound or music is added after filming e.g. orchestral music used to augment a mood, or a pop song accompanying a montage sequence. It is always worth thinking about why a particular music has been chosen and what it adds to the film. Sound can also be important in editing as it helps make the connection between shots. Sometimes a sound (often a line of dialogue) begun in one shot will continue in the next. This is known as a sound bridge.