File - Hannah Childs Wilson

advertisement

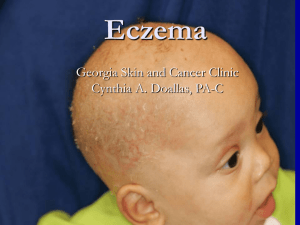

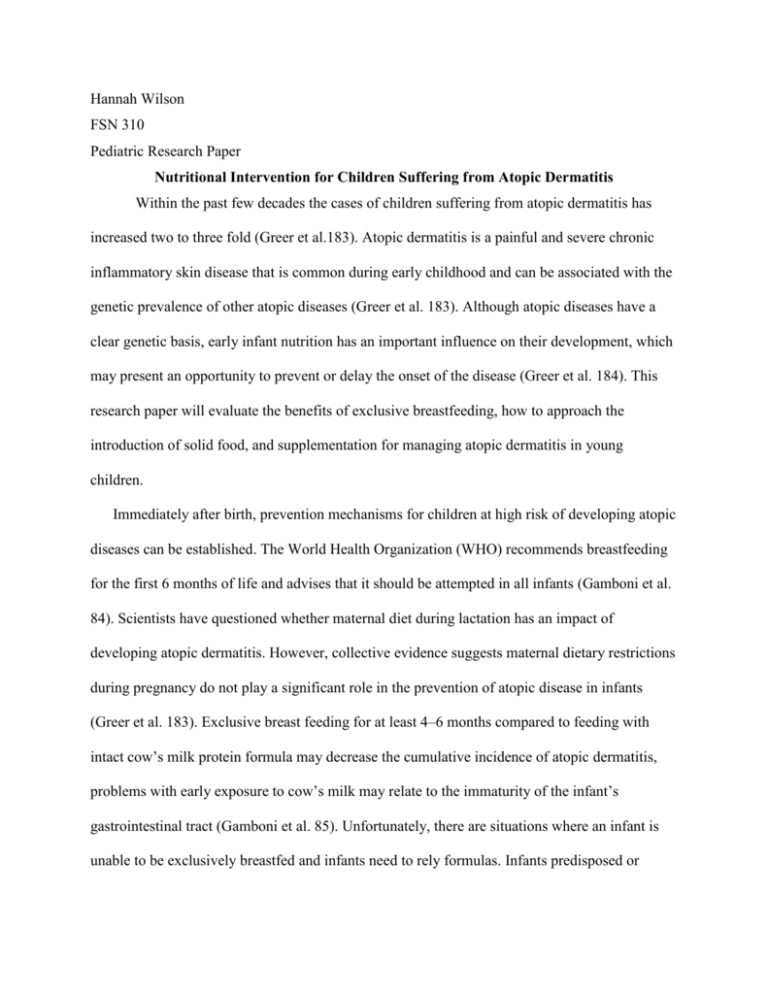

Hannah Wilson FSN 310 Pediatric Research Paper Nutritional Intervention for Children Suffering from Atopic Dermatitis Within the past few decades the cases of children suffering from atopic dermatitis has increased two to three fold (Greer et al.183). Atopic dermatitis is a painful and severe chronic inflammatory skin disease that is common during early childhood and can be associated with the genetic prevalence of other atopic diseases (Greer et al. 183). Although atopic diseases have a clear genetic basis, early infant nutrition has an important influence on their development, which may present an opportunity to prevent or delay the onset of the disease (Greer et al. 184). This research paper will evaluate the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding, how to approach the introduction of solid food, and supplementation for managing atopic dermatitis in young children. Immediately after birth, prevention mechanisms for children at high risk of developing atopic diseases can be established. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life and advises that it should be attempted in all infants (Gamboni et al. 84). Scientists have questioned whether maternal diet during lactation has an impact of developing atopic dermatitis. However, collective evidence suggests maternal dietary restrictions during pregnancy do not play a significant role in the prevention of atopic disease in infants (Greer et al. 183). Exclusive breast feeding for at least 4–6 months compared to feeding with intact cow’s milk protein formula may decrease the cumulative incidence of atopic dermatitis, problems with early exposure to cow’s milk may relate to the immaturity of the infant’s gastrointestinal tract (Gamboni et al. 85). Unfortunately, there are situations where an infant is unable to be exclusively breastfed and infants need to rely formulas. Infants predisposed or already experiencing symptoms of atopic dermatitis, hypoallergenic hydrolyzed infant formals may replace breastfeeding to avoid potential allergies from soy or milk based formulas (Greer et al. 183). Deciding when to introduce complementary foods is the next initiative mothers can take to help prevent the onset of atopic dermatitis. The gut has a large antigenic load that develops overtime and it’s thought that the age of food exposure must play a role in the prevention of or predisposition to allergic disease (Abrams, Becker, 721). A recent literary review identified 2719 article citations and critically evaluated 13 studies that confirmed early solid feeding (before the age of 4 months) increases the risk of allergic disease (Gamboni et al. 85). Thus, health professional agree that the introduction of solids should be around 4 to 6 months for optimal prevention (Gamboni et al. 85). There are several solid foods that mothers should pay extra attention to during the introductory phase, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends delaying the introduction of cow’s milk until 1 year of age, egg until 2 years of age, and peanut, tree nut, and fish until 3 years of age (Abrams, Becker, 721). Various chemical ingredients, such as flavoring agents and preservatives commonly found in processed foods, are also frequently restricted from the diets of children suffering from atopic dermatitis (Lim et al. 55). Despite the handful of highrisk foods, introducing a variety of foods during this time may have beneficial effects. It appears that early exposure to allergens, from around 4–6 months of age (opposed to very at less than 4 months) may actually allow the infant’s immune system to become tolerant and prevent the allergic sensitization to food (Gamboni et al. 87). In conclusion, the timing and types of food be introduced to young children impact prevention of atopic dermatitis by reducing exposures to pathogens from food and increasing tolerance by eating a variety of non-risk foods. Despite commonly practiced efforts to reduce environmental exposures to children, atopic dermatitis continues to rank as the most common allergic disease, causing countless children to suffer from various physical problems due to frequent skin damage and itchy sensation (Hyunjin et al. 2287). As one could imagine, such stress and aggravation during a vital time of development can have serious impacts on the child’s life. Atopic dermatitis can indirectly disrupt friendships, learning performance, and family relationships, thus negatively influence the child’s life (Hyunjin et al. 2287). There are several supplements that are thought to aid in treating atopic dermatitis and improve overall quality of life in addition to the physical problems associated with this disease. For example, vitamin D has been a significant area of research as dietary supplement for treatment of atopic dermatitis. In its active form, dihydroxyvitamin D promotes antimicrobial peptide (AMP) gene expression inducing antimicrobial properties and immune system signaling (Searing et al. 399). Antimicrobial peptide activity is only one potential benefits of vitamin D supplementation, research indicates potential for vitamin D to suppress inflammatory responses and promote the integrity of the intestineds (Searing et al. 399). Correspondingly, vitamin D supplementation provides a possible therapeutic intervention for a variety of skin disorders including atopic dermatitis (Searing et al. 399). Another potential supplement for treating symptoms of atopic dermatitis is the use of probiotics. According to clinical findings, probiotic administration of especially L. rhamnosus GG to infants at high risk of atopy appeared effective for prevention of development of atopic dermatitis (Betsi et al. 2). Probiotic treatment for one or two months appeared to also reduce the severity of atopic dermatitis, but probiotics had little effect on most of the inflammatory markers measured (Betsi et al. 3). The food, dose, frequency, age of introduction, and genetic predisposition of the child might all play important roles allergenic diseases. It is important that health care providers to educate new mothers on the role of introducing foods to their children in effort to decrease the prevalence of atopic dermatitis. Additionally, the administration of vitamin D supplements and probiotics are two mechanisms to decrease irritable symptoms and foster the growth of a healthy and happy child. Atopic dermatitis, along with other food allergies in children is a continuing area of research with more prevention and treatment mechanisms to be found. Work Cited Gamboni SE, Allen KJ, Nixon RL, Infant feeding and the development of food allergies and atopic eczema: An update. Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 2013; 54: 85–89. Review Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks W. Effects of Early Nutritional Interventions on the Development of Atopic Disease in Infants and Children: The Role of Maternal Dietary Restriction, Breastfeeding, Timing of Introduction of Complementary Foods, and Hydrolyzed Formulas. The Official Journal of The American Academy of Pediatrics. 2008; 121: 183-191 Betsi GI, Papadavid E, Falagas ME. Probiotics for the treatment or prevention of atopic dermatitis: a review of the evidence from randomized controlled trials. National Institute for Health Research. 2014; 1-3 Searing DA, Leung YM. Vitamin D in Atopic Dermatitis, Asthma and Allergic Diseases. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am . 2010 August ; 30(3): 397–409. Lim H, Song K, Sim J, Park E, Kangmo A, Kim j, Han Y. Nutrient Intake and Food Restriction in Children with Atopic Dermatitis. Clinical Nutrition Research. 2013;2:52-58