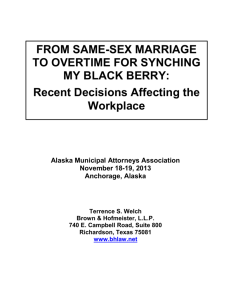

Id - Brown and Hofmeister

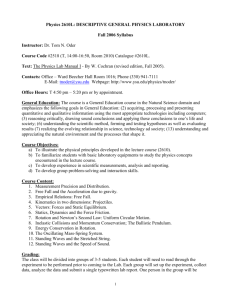

advertisement