CLOSING ARGUMENTFina..

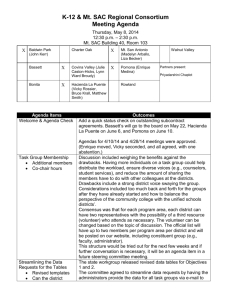

advertisement

CLOSING ARGUMENT (3/2/11) Undisputed on Plaintiffs motion before the Supreme Court that SFRA was not fully funded in 2010-11, with the State having reduced K-12 state aid by $1.08 billion from the 2009-10 level A) Special Master and parties are well aware of the limited issue on remand, as set forth in Remand Orders #1 and #2 Given the State’s reduction in aid, can NJ Districts with varying concentrations of at-risk students provide the Comprehensive CCCS to all students at current levels of funding through the SFRA? Are districts able to deliver the CCCS to their students this school year with the current, reduced level of funds provided by the State? Court's remand orders make clear about several factors: 1) the comprehensive CCCS mean all nine content areas in the CCCS, and not just language arts, math and science, the areas assessed annually by the State; 2) "all" means that the CCCS must be delivered to all students, not a majority or some other subset of those students; 3) "current funding levels through the SFRA" means in the funding actually allocated to districts in FY11, not prior or future school years; 4) "districts with low, medium and high concentrations of at-risk students" means that the delivery of the CCCS must be examined not just statewide or in some limited subset of districts, but with a particular focus on at-risk students in the range of NJ districts with varying enrollment levels of those students. B) Remand Orders are also clear on another critical issue: the State has the burden of proof on the limited remand issue, not plaintiffs Further, comparing how the state aid reduction was allocated among districts, or among categories of districts, and the resulting funding levels, is not sufficient for State to meet its burden. This comparative data is already before the Supreme Court – on remand, the State must do more—it must demonstrate that those reductions had no negative effect on the ability of districts with varying concentrations of at-risk students to deliver the CCCS to all students in the 2010-11 school year. C) In the remand proceeding, State attempted to meet its burden by presenting proofs that there is an insufficient correlation or relationship between funding and student outcomes. 1) Heard the testimony of Eric Hanushek, who formed his opinion that NJ could cut 5-10% -- or even more – without any effect on a thorough and efficient education, in 15 minutes during an initial phone call with Def. Counsel. But Mr. Hanushek conceded that his opinion is based on national data going back to 2007-08, that he had not analyzed current funding levels in NJ school districts or the impact of the aid reduction on programs, services and positions in districts, and even that he had any knowledge of NJ’s CCCS and their pivotal role as the measure of a T&E education for NJ students. 2) Then we had the testimony of Bari Erlichson of the DOE in which she presented scatterplots she prepared charting last year’s State test results in language arts and math against districts FY10 spending relative to the SFRA adequacy level. While Dr. Erlichson could only surmise that her scatterplots appeared to show a lack of a relationship between districts’ spending level and test scores, she admitted that they also show a pattern of lower outcomes and district wealth or poverty. Bottom line: neither Hanushek nor Erlichson offered any evidence related to the specific issue on remand and that might help the State meet its burden. B) State next presented evidence, through DOE analyist Kevin Dehmer, on the State’s 1.083 billion reduction in K-12 aid, and making comparisons of how the reductions were allocated among districts – much of the same data already before the Supreme Court; and data which Remand Order #1 makes clear is insufficient to meet the State's burden. But Mr. Dehmer also presented a critical piece of relevant evidence -- for the first time on this motion and in response to an inquiry from the Special Master -- a simulation demonstrating the levels of state aid that would be required to fully fund the SFRA in FY11, using the parameters in the formula. Mr. Dehmer's demonstrated that the State reduced SFRA formula aid, not just by 1.08 billion, but by $1.6 billion statewide from the level required by the SFRA formula (full funding in FY11). C) Mr. Dehmer's testimony that the State reduced formula aid by $1.6 billion, or almost 19% of all state aid, was then confirmed by Plaintiff’s school finance expert Mr. Wyns, who further analyzed the State's data on the required level of funding under SFRA and its’ impact on the funding levels of districts with low, medium and high concentrations of at-risk students. Mr. Wyns undisputed testimony demonstrated that: a) The State’s underfunding of the SFRA impacted high poverty districts the most, with those districts experiencing an aid loss of approximately $1500 per pupil b) The State’s underfunding of the SFRA resulted in an increase in the number of districts spending below their SFRA defined adequacy level, from 161 to 205, and for the 161 districts below adequacy in 2009-10, they moved significantly further below their adequacy level in the current year. c) 135 of the 205 districts with current funding levels below SFRA adequacy are districts with medium and high concentrations of at risk students. 72% of all at-risk students in the state are now in districts spending below SFRA adequacy. Given this analysis, Mr. Wyns opinion was firm and undisputed: the growing number of districts below SFRA adequacy do not have current funding to provide the CCCS to their students, at the level prescribed by the SFRA formula. Finally, State brought forward four district superintendents, who testified under subpoena, from the Piscataway, Woodbridge, Montgomery Tp and Bridgeton districts. The testimony of these superintendents, along with the superintendents of Clifton and Buena Regional, we’re remarkably consistent: a) all are spending under their SFRA adequacy level and moved further away from that level as a result of the State’s aid cut b) in making budget cuts, all attempted to keep the instructional component of the CCCS curriculum intact, but some had to reduce or eliminate instructional programs in the world languages, technology, and career education areas of the CCCS. And they also cut their teacher corps, resulting in increased class sizes at all grade levels. c) all made cuts in critical supports for students and teachers, programs that they made clear are essential to the delivery of the CCCS, particularly for at-risk, LEP students, students with disabilities and students otherwise at risk of academic failure. These cuts included librarians, guidance counselors, technology teachers, teachers and tutors for students behind in language arts and math, nurses, security personnel, instructional supervisors, assistant principals, professional development and other critical supports. d) all spelled out their heroic efforts to achieve reasonable and legal efficiencies in their budgets and to redirect saved funds into instruction and student and teacher support programs e) and all made clear that, because of the program and staff reductions they were compelled to make as a result of the State’s aid reduction, they cannot provide and deliver the comprehensive CCCS to all of their students in the current school year. What’s so striking about this record is that the State never brought forward a single witness from any district to testify that their district could provide the CCCS to all students, particularly those students at-risk and with special needs, at the current funding level. In closing, on this record, the State has clearly not met its burden on the limited remand issue. The State has not attempted to show that districts throughout the State are providing the CCCS on reduced funds. They’ve not even shown one district that is doing so. What they have demonstrated is that, their failure to fund the SFRA formula in the current year, has caused more districts to fall further behind the resource adequacy threshold set by the formula as necessary to provide the CCCS. Two years ago the State argued strenuously -- based on a five year intensive development process and lots of expert testimony -- that the SFRA resolved the longstanding, central issue at the heart of the Abbott litigation: it defined the funding required for all districts to provide T&E, as measured by the CCCS. The Supreme Court accepted that formula. While the State may have now changed its mind about the SFRA formula, that ship has sailed. Based on this record, Plaintiffs respectfully request the Special Master conclude that the State has not met its burden of demonstrating that districts can provide the CCCS to all students at current funding levels.