pubdoc_12_18604_999

advertisement

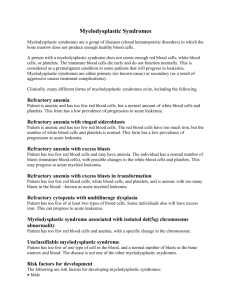

Myelodysplastic syndrome Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) consists of a group of clonal haematopoietic disorders which represent steps in the progression to the development of leukaemia. MDS presents with consequences of bone marrow failure (anaemia, recurrent infections or bleeding), usually in older people (median age at diagnosis is 69 years). The blood film is characterised by cytopenias and abnormal-looking (dysplastic) blood cells, including macrocytic red cells and hypogranular neutrophils with nuclear hyper- or hyposegmentation. The bone marrow is hypercellular, with dysplastic changes in all three cell lines. Blast cells may be increased but do not reach the 20% level that indicates acute leukaemia. Chromosome analysis frequently reveals abnormalities, particularly of chromosome 5 or 7. Inevitably, MDS progresses to AML, although the time to progression varies (from months to years) with the subtype of MDS, being slowest in refractory anaemia and most rapid in refractory anaemia with excess of blasts. An international prognostic scoring system (IPSS) predicts clinical outcome based upon karyotype and cytopenias in blood, as well as percentage of bone marrow blasts. In low-risk patients, median survival is 5.7 years and time for 25% of patients to develop AML is 9.4 years; equivalent figures in high-risk patients are 0.4 and 0.2 years, respectively. WHO classification of myelodysplastic syndromes Refractory anaemia (RA) Blasts < 5% Erythroid dysplasia only Refractory anaemia with sideroblasts (RARS) Blasts < 5% Ringed sideroblasts > 15% Refractory cytopenias with multilineage dysplasia (RCMD) Blasts < 5% 2–3 lineage dysplasia Refractory anaemia with excess blasts (RAEB) Blasts 5–20% 2–3 lineage dysplasia Myelodysplastic syndrome with 5q− Myelodysplastic syndrome associated with a del (5q) cytogenetic abnormality Blasts < 5% Often normal or increased blood platelet count Myelodysplastic syndrome Unclassified None of the above or inadequate material Management For the vast majority of patients who are elderly, the disease is incurable, and supportive care with red cell and platelet transfusions is the mainstay of treatment. A trial of erythropoietin and granulocyte– colony-stimulating factor (G–CSF) is recommended in some patients with early disease to improve haemoglobin and white cell counts. For younger patients with higher-risk disease, allogeneic HSCT may afford a cure. Transplantation should be preceded by intensive chemotherapy in those with more advanced disease. More recently, the hypomethylating agent azacytidine has improved survival by a median of 9 months for high-risk patients,