chapter 1 - introduction - International Journal of Advances in

advertisement

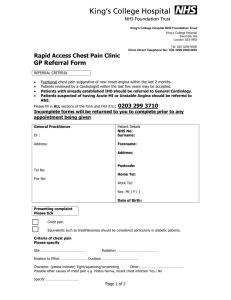

1 CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION: 1.1 BACKGROUND: Unexplained chest pain (UCP) is a common reason for emergency hospital admission and generates considerable health-care costs for society. Previous studies have often defined UCP as non-cardiac chest pain (NCCP), i.e. chest pain that had not been diagnosed as acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or ischemic heart disease (IHD) by a physician. Galmiche et al, has developed three diagnostic criteria for functional chest pain of presumed esophageal origin, 1) Midline chest pain or discomfort that is not of burning quality. 2) Absence of evidence that gastroesophageal reflux is the cause of the symptom. 3) Absence of histopathology- based esophageal motility disorders". Psychological factors e.g. anxiety and somatisation disorders will also have an impact on the functional chest pain. Terminology "unexplained chest pain", i.e. chest pain, which after investigation has proven to be unrelated to the heart, might be confusing but is still preferable to "non-cardiac"[NCCP] or "atypical chest pain". A variety of names have also been used in describing patients with NCCP. “chest pain of undetermined origin, unexplained chest pain, functional chest pain, soldier’s heart, irritable heart, sensitive heart, neurocirculatory asthenia, DaCosta’s syndrome, and chest pain with normal coronary angiograms”. In patients with NCCP, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, musculoskeletal, infectious, drug-related, and psychological disorders are considered. However, esophageal conditions are considered to be the most common contributing factor for angina-like chest pain of non-cardiac origin.1 Psychiatric conditions are common in NCCP. Several studies have noted a variable prevalence of panic disorders (24%–70%), anxiety (33%–50%), and major depression (11%–22%).2 Women with high anxiety sensitivity report more chronic pain than women with low anxiety sensitivity. No similar relationship was found for men. Gender differences are also seen in the diagnosis of chest pain, with male patients more likely than women to be diagnosed with cardiac chest pain instead of non-cardiac chest pain, in accordance with their higher overall risk of IHD.3 Studies of patients with a non-cardiac/non-coronary diagnosis of chest pain often include 2 patients with other defined causes of chest pain, e.g. gastro-esophageal, respiratory and musculoskeletal disorders. However, a considerable number of the patients with a non-cardiac/coronary diagnosis do not have a clearly defined explanation for their chest pain. Atypical chest pain has been reported to account for 49– 60% of all admissions with chest pain. Such patients are often discharged without follow-up, though many experience recurrent symptoms, and the lack of a firm diagnosis can result in depression, anxiety and a decrease in daily activity. Such reactions have been ascribed directly to the absence of reassurance that symptoms do not indicate lifethreatening disease.4 Chest pain occurs frequently in the community and is usually benign. Despite this, myocardial ischemia remains important, because it is potentially fatal. This leads to an understandable tendency to over investigate, so that as few as 11–44% of patients referred to cardiac outpatient clinics have evidence of organic disease, and up to 31% of patients receiving coronary angiography are shown to have normal coronary anatomy (NCA).5 1.2 EPIDEMIOLOGY: Chest pain is the presenting symptom in about 12% of emergency department visits in the United States and has a one-year mortality of about 5%. It is possible to find an organic cause just for 1/3 of patients admitted to hospital with chest pain. For the other 2/3 we are dealing with Unexplained Chest Pain. The epidemiology of chest pain differs markedly between outpatient and emergency settings. Cardiovascular conditions such as myocardial infarction (MI), angina, pulmonary embolism (PE), and heart failure are found in more than 50% of patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain, but the most common causes of chest pain seen in outpatient primary care are musculoskeletal conditions, gastrointestinal disease, stable coronary artery disease (CAD), panic disorder or other psychiatric conditions, and pulmonary disease. Unstable CAD rarely is the cause of chest pain in primary care, and around 15% of chest pain episodes never reach a definitive diagnosis. Despite these figures, when evaluating chest pain in primary care it is important to consider serious conditions such as stable or unstable 3 CAD, PE, and pneumonia, in addition to more common (but less serious) conditions such as chest wall pain, peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and panic disorder. Many studies demonstrated that in a high percentage of people that suffer of UCP there are mental disorders and unfavorable social and psychological factors. The present study will use the term Unexplained Chest Pain (UCP). Most studies of UCP are concerned without patients with normal coronary angiograms. In one study, 61% of patients with UCP had psychiatric symptoms on structured interview (the Clinical Interview Schedule), compared to 23% of patients with abnormal coronary arteries.6 1.3 CLASSIFICATION OF UCP: The sources of NCPP can be grouped into esophageal and non-esophageal. Several studies have shown that approximately 60% or more of patients with NCCP suffer from esophageal pain (mostly due to acid reflux commonly referred to as Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD). 1. Esophageal Sources of NCCP: a) Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) or acid reflux, the most common cause of esophageal NCCP. In addition to chest pain, patients may complain of heartburn and or regurgitation or chest pain alone may be due GERD. b) Esophageal contraction disorders as cause of NCCP, include disorders of esophagus muscle (esophageal motility disorders) such as uncoordinated muscle contractions (esophageal spasm), contractions of extremely high pressure (nutcracker esophagus), and occasionally a disorder characterized by absence of esophageal muscle contraction due to loss of nerve cells of the esophagus (achalasia). It is important to recognize particularly achalasia since is a treatable disorder. c) Visceral (esophageal) Hypersensitivity in patients with NCCP may have an esophagus where the smallest change in pressure or exposure to acid may result in tremendous pain. This is best explained by describing an experiment: when a small balloon is placed inside the (esophagus) and distended, patients with NCCP perceive the distension of the balloon at very low volumes. This is 4 unlike healthy control subjects do not experience this pain at all or may only have pain when the balloon distension reaches very large volumes. Although the cause of this increased sensitivity to balloon distension is unknown, there are treatment modalities that can be used to improve this exaggerated pain perception. 2. Non-esophageal Causes of NCCP: Non-esophageal sources that can cause NCCP include: Musculoskeletal conditions of the chest wall or spine, pulmonary (lung) disorders, pleural illness (the layers of tissue that cover the lungs), pericardial conditions (the layer of tissue that protects the heart) and even digestive disorders such as ulcers, gallbladder, pancreatic diseases and rarely tumors (particularly in patients past age 50). 1.4 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA: Patients with normal or insignificant (50%) coronary artery narrowing were shown to have a 1% mortality rate from cardiac causes in a 7-yr follow-up study. Thus, a negative angiogram provides strong evidence to reassure patients that their recurring chest pains are not life-threatening. Unfortunately, even after cardiac disease has been ruled out, most patients continue to have recurring chest pain and compromised lifestyles, and many believe that they still have heart disease.7 Few studies compared the prevalence of lifetime psychiatric disorders and current psychological distress among three consecutive series of patients with chronic chest or abdominal pain: (1) Patients with non-cardiac chest pain and clinically significant upper gastrointestinal disorders; (2) Patients with non-cardiac chest pain and no upper gastrointestinal disorders; and (3) Patients with recurrent biliary colic. These concluded that Patients with non-cardiac chest pain and no upper gastrointestinal disease had a higher proportion of panic disorder (15%), obsessivecompulsive disorder (21%), and major depressive episodes (28%) than patients with gallstone disease (0%, p<0.02; 3%, p<0.02; and 8%, p<0.05, respectively).8 5 1.5 TREATMENT: Treatment of NCCP is challenging because of the heterogeneous nature of the disorder. 1. Acid suppression: Several open-label studies have demonstrated efficacy of acid suppression with either PPIs or histamine H2-receptor antagonists following the first description by DeMeester et al. in 1982.9 Since the first double-blind, placebo-controlled study of acid suppression in NCCP by Achem et al. 10,11 Similar controlled studies have consistently shown efficacy of PPI treatment in NCCP. 2. Smooth muscle relaxants: Nitrates, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, anticholinergic drugs, and calcium channel blockers have been used in the treatment of NCCP with dysmotility. Most studies included small numbers, and few were placebo controlled, which prevents us from making any firm conclusions about the efficacy of these agents. 3. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): A few clinical trials have evaluated the effect of TCAs in NCCP. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial12 in 60 patients, imipramine (50 mg) significantly reduced chest pain episodes in 52% of patients. Prakash and Clouse13 demonstrated that 75% of NCCP patients experience symptomatic relief during long-term use of TCAs for up to 3 years. 4. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: In a double-blind, controlled study of sertraline versus placebo in 30 NCCP patients for 8 weeks, sertraline demonstrated a significant reduction in pain score compared with placebo.14 However, another study15 found no differences between paroxetine and placebo. Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs): Recently, Lee et al. evaluated venlafaxine vs. placebo in a double-blind controlled study in NCCP, reporting that 52% of patients experienced symptom improvement in comparison to 4% of those taking a placebo.16 5. Miscellaneous treatments: Symptomatic improvement has been reported in NCCP patients taking adenosine intravenously as well as orally. Small-scale studies have shown improvement with endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and hypnotherapy.17 6 CHAPTER 2 - REVIEW OF LITERATURE: K Y Ho et al.: Non-cardiac, non-oesophageal chest pain: the relevance of psychological factors.8 In this study, the Diagnostic Interview Schedule and the 28 item General Health Questionnaire were administered to all patients. Patients with non-cardiac chest pain and no upper gastrointestinal disease had a higher proportion of panic disorder (15%), obsessive-compulsive disorder (21%), and major depressive episodes (28%) than patients with gallstone disease (0%, p<0.02; 3%, p<0.02; and 8%, p<0.05, respectively). In contrast, there were no differences between patients with non- cardiac chest pain and upper gastrointestinal disease and patients with gallstone disease in any of the DSM-111 defined lifetime psychiatric diagnoses. Using the General Health Questionnaire, 49% of patients with non-cardiac chest pain with- out upper gastrointestinal disease scored above the cutoff point (i.e., more than 4), which was considered indicative of nonpsychotic psychiatric disturbance, whereas only 14% of patients with gall- stones did so (p<0.005). The proportions of such cases were however similar between patients with non-cardiac chest pain and upper gastrointestinal disease (27%) and patients with gallstones. Conclusions—Psychological factors may play a role in the pathogenesis of chest pain that is neither cardiac nor oesophaglogastric in origin. G. D. Eslick et al.: Non-cardiac chest pain: predictors of health care seeking, the types of health care professional consulted, work absenteeism and interruption of daily activities.18 In this study, a total of 212 patients who presented to a Tertiary Hospital Emergency Department over a 1-year period with acute chest pain were assessed according to a standard diagnostic protocol and completed the Chest Pain Questionnaire (CPQ). : In the previous 12 months prior to presentation to the Emergency Department, 78% of patients had seen a health care professional for chest pain. The main health care professionals seen were general practitioners (85%), cardiologists (74%) and gastroenterologists (30%). Work absenteeism rates because of non-cardiac chest pain were high (29%) as were interruptions to daily activities (63%). Multiple logistic regression found that acid regurgitation was the only independent predictive symptom associated with consulting for non-cardiac chest pain (OR ¼ 3.97, 95% CI: 1.25– 12.63). 7 Conclusions: Consulting for chest pain is common is this group of patients. The type of health care professional seen appears to be moderated by the frequency and severity of reflux symptoms among these chest pain patients. Work absenteeism and interruptions to daily activities is high among chest pain sufferers. Lynette Spalding et al.: Cause and outcome of atypical chest pain in patients admitted to hospital.19 The study population was 250 patients admitted over five weeks with chest pain suspected of being cardiac in origin. Initial assessment included an electrocardiogram and measurement of troponin-T. If neither of these indicated a cardiac event, the patient was deemed to have ‘atypical’ chest pain and the cause, where defined, was recorded. Outcomes at one year were determined by questionnaire and by assessment of medical notes. Of the 250 patients, 142 had cardiac pain (mean age 79 years, 58% male) and 108 atypical chest pain (mean age 60 years, 55% male). Of those with atypical pain, 40 were discharged without a diagnosis; in the remaining 68 the pain was thought to be musculoskeletal (25), cardiac (21), gastrointestinal (12) or respiratory (10) in origin. 41 patients were given a follow-up appointment on discharge. At one year, data were available on 103 (96%) patients. The mortality rate was 2.9% (3 patients) compared with 18.3% in those with an original cardiac event. Half of the patients with atypical pain had undergone further investigations and 14% had been readmitted. The yield of investigative procedures was generally low (20%) but at the end of the year only 27 patients remained undiagnosed. Cecilia Cheng et al.: Psychosocial Factors in Patients With Noncardiac Chest Pain.20 A matched case-control design was adopted to compare differences in psychosocial factors among a target group of patients with NCCP (70), a pain control group of patients with rheumatism (70), and a community control group of healthy individuals (70). Results: Compared with subjects from the two control groups, NCCP patients tended to monitor more, use more problem-focused coping, display a coping pattern with a poorer strategy-situation fit, and receive less emotional support in times of stress. Moreover, monitoring perceptual style and problem-focused coping were associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression. Coping pattern with a strategy-situation fit and emotional support were related to lower levels of anxiety and depression. Conclusions: The present 8 new findings suggest that monitoring perceptual style and inflexible coping style are risk factors that enhance one’s vulnerability to NCCP. Emotional support may be a resource factor that reduces one’s susceptibility to NCCP. Steve R Kisely1 et al.: Psychological interventions for symptomatic management of non-specific chest pain in patients with normal coronary anatomy.21 Conducted Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with standardized outcome methodology that tested any form of psychotherapy for chest pain with normal anatomy. Diagnoses included non-specific chest pain (NSCP), atypical chest pain, syndrome X, or chest pain with normal coronary anatomy (as either inpatients or outpatients). There was a significant reduction in reports of chest pain in the first three months following the intervention; fixed-effect relative risk = 0.68 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.81). This was maintained from three to nine months afterwards; relative risk = 0.59 (95% CI 0.45 to 0.76). This review suggests a modest to moderate benefit for psychological interventions, particularly those using a cognitive-behavioral framework, which was largely restricted to the first three months after the intervention. Hypnotherapy is also a possible alternative. The evidence for brief interventions was less clear. Further RCTs of psychological interventions for NSCP with follow-up periods of at least 12 months are needed. J Mant et al.: Systematic review and modeling of the investigation of acute and chronic chest pain presenting in primary care.22 Concluded that for acute chest pain, no clinical features in isolation were useful in ruling in or excluding an acute coronary syndrome (ACS), although the most helpful clinical features were pleuritic pain (LR+ 0.19) and pain on palpation (LR+ 0.23). ST elevation was the most effective ECG feature for determining MI (with LR+ 13.1) and a completely normal ECG was reasonably useful at ruling this out (LR+ 0.14). Results from ‘black box’ studies of clinical interpretation of ECGs found very high specificity, but low sensitivity. In the simulation exercise of management strategies for suspected ACS, the point of care testing with troponins was cost-effective. Where an ACS is suspected, emergency referral is justified. ECG interpretation in acute chest pain can be highly specific for diagnosing MI. Point of care testing with troponins is cost-effective in the triaging of patients with suspected ACS. Resting ECG and exercise ECG are of only limited value in the diagnosis of coronary heart disease (CHD). The potential advantages of rapid access chest pain clinics 9 (RACPCs) are lost if there are long waiting times for further investigation. Recommendations for further research include the following: determining the most appropriate model of care to ensure accurate triaging of patients with suspected ACS; establishing the cost- effectiveness of pre-hospital thrombolysis in rural areas; determining the relative cost-effectiveness of rapid access chest pain clinics compared with other innovative models of care; investigating how rapid access chest pain clinics should be managed; and establishing the long-term outcome of patients discharged from RACPCs. 10 CHAPTER 3 - AIMS AND OBJECTIVES: 3.1 AIMS: The major aim of the thesis was to provide a comprehensive assessment of the UCP experience. Further aims were to determine psychosocial factors associated with UCP and how the symptom experiences affect everyday life and health-related quality of life. 3.2 OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY: Primary objective: To investigate the effect of psychosocial risk factors in men and women with non-cardiac chest pain. Secondary Objective: To assess the risk factors of chest pain in men and women. Age wise and gender wise distribution of Unexplained Chest Pain. To assess the effect of UCP on everyday life. 3.3 OUTCOMES OF THE STUDY: The differential effects of psychosocial factors in between patient group and reference group. The differential effects of psychosocial factors in between men and women. 11 CHAPTER 4 - MATERIALS AND METHODS: 4.1 STUDY SITE: The study was conducted in the General Medicine and Surgery departments of SVS Medical College Hospital, Mahabubnagar which is a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital which has 900 beds with Multi specialty departments. 4.2 STUDY DESIGN: The study was an observational study. 4.3 STUDY PERIOD: The study was conducted over a period of six months starting from March 2014 to August 2014. 4.4 STUDY APPROVAL: This study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee (IEC). 4.5 SAMPLES: 4.5.1 The patient group: The study was conducted in Out-Patient Department of General Medicine. 60 patients between 16–69 years of age, who were, 1) Evaluated for acute chest pain and judged by a physician to have no organic cause of their chest pain and 2) Free from any history of heart disease were considered for inclusion in the study. They were asked about participation by the investigators, thereafter written and verbal information about all the steps in the study was provided. After written informed consent was obtained, the patients filled in a questionnaire providing background characteristics and data on psychosocial factors, before being discharged. 4.5.2 The Reference Group: General population was taken under Reference group. 60 reference participants were assessed according to the protocol. The psychological assessment was conducted after the basic examination. 12 4.6 STUDY CRITERIA: 4.6.1 Inclusion Criteria: Inpatients and Outpatients. Patients of either sex with age between 16- 69 years. Patients who were evaluated by the physician to have no organic cause for their chest pain. Patients free from any history of heart disease. 4.6.2 Exclusion Criteria: Patients who are not willing to give the consent. Pregnant/lactating women. Patients with previous MI/Angina. 4.7 STUDY MATERIALS: 4.7.1 Informed consent form, an informed consent form was prepared for patients’ understanding and agreeing to participate in the study. 4.7.2 Patient data collection form, contains the socio-demographic details of the patient like age, sex, education, occupation, and annual income, social and family history, stress periods, marriage or cohabilitation. 4.7.3 Social interaction and communication skills Questionnaire: It contains a total of 20 questions. Each question is given 1-5 options. 1- not able to perform with assistance, 2- able to perform with two or more verbal prompts, 3- able to perform with less than two verbal prompt, 4- Able to perform with minimal assistance (Gesture) 5- Able to perform independently. At last all the scores of questions are added to obtain final score. Severity is assessed. − 90: Social Interaction skills exceed expectations − 70-89: Social Interaction skills meet expectations − 50-69: Social Interaction skills sub standard to expectations − 30-49: Social Interaction skills below expectations − < 29: Social Interaction skills far below expectations 13 4.7.4 Zung-self rating depression scale: It contains a total of 20 questions. Each question is given options as A little of time, some of the time, Good part of the time, Most of the time. At last all the scores of questions are added to obtain final score. Severity is assessed. − 20-44 – Normal Range − 45 – 59 – Mildly depressed − 60 – 69 – Moderately depressed − ≥70 – Severely depressed. 4.7.5 Triat- anxiety scale: It contains a total of 20 questions. Each question is given options as 1-almost never; 2- sometimes; 3- often; 4- almost always. . At last all the scores of questions are added to obtain final score. Severity is assessed. − 20 – 44 – Normal. − 45 – 59 – Mild. − 60 – 69 – Moderate. − ≥70 – sever. 4.7.6 SF-36(tm) Health Survey: This contains 12 sub-scales which have a total of 36 questions, each question caries 0 – 100 marks. Averages of the sub-scales are taken into consideration. 4.8 STUDY PROCEDURE: A consecutive sample of patients with chest pain, who presented to SVS Medical Hospital, General Medicine Department (a tertiary teaching and referral hospital) over a 4months period was enrolled in the study. Patients were followed through to general admission in the outpatient (OP) department of General Medicine. On presentation, all subjects were invited to participate in the study. An information package was provided. 14 This included a letter describing the study, and a patient consent form (requiring a signature), which gives permission to access the patient’s medical records and the Chest Pain Questionnaire Annexures (CPQA). The CPQA incorporates several existing validated and widely used instruments including Social interaction and attachment scales, Anxiety and Depression Scale (used to assess anxiety and depression), the SF-36 (used to assess general health status), Data is collected using patient data collection based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Two groups are required for this study of which one is patient group the other is reference group. Patients from the patient group and reference participants from the reference group are assessed accordingly. The psychological assessment was conducted after the basic examination. They were asked about participation by the investigators, thereafter written and verbal information about all the steps in the study was provided. After written informed consent was obtained, the patients filled in a questionnaire providing background characteristics and data on psychosocial factors, before being discharged. 4.9 STATISTICAL ANALYSIS: Patient demographic and clinical characteristics have been reported as mean and S.D. or confidence interval (CI) for numeric-scaled features and percentages for discrete characteristics. All psychological and quality of life scores are presented as a mean ± S.D. 15 CHAPTER 5 – RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS During the study a total of 60 patients with UCP visited Emergency Department (ED), of which, 33 were male and 27 were female. 60 participants from general population were considered as referents of which 22 were male and 38 were female. TABLE 5.1: GENDER WISE DISTRIBUTION IN PATIENT GROUP AND REFERENCE GROUP: Total Males Females Patient group 60 33 27 Reference group 60 22 38 70 60 60 No. of people 60 50 40 38 33 27 30 22 20 10 0 Patient group Total Reference group Males Females Figure 5.1: Gender wise distribution in patient group and reference group. The total number of people participated are 120. In which 60 are patients suffering from UCP and the other group of 60 are from the general population, considered as referents. Patient group consisted of 33 males and 27 females, while referents group consisted of 22 males and 38 females (Figure 5.2). The incident rate of UCP is more in males 55%, than in females 45%. 16 TABLE 5.2: AGE WISE DISTRIBUTION IN PATIENT GROUP AND REFERENCE GROUP: Reference group Age Patient group (n=60) 10-20yrs 8 9 21-30yrs 18 34 31-40yrs 18 12 41-50yrs 7 2 51-60yrs 9 3 61-70yrs 0 0 (n=60) 40 34 35 No. of people 30 Patient group 25 18 20 15 10 18 12 8 9 5 Referen ce group 9 7 2 3 0 0 0 10-20yrs 21-30yrs 31-40yrs 41-50yrs 51-60yrs 61-70yrs Figure 5.2: Age wise distribution in patient group and reference group. When it comes to the age group the highest number participants are found to be in between 21-30yrs then by 31-40yrs, 10-20yrs, 51-60yrs, 41-50yrs with a number of 52, 30, 17, 12 and 9 respectively (Figure 5.2). 17 TABLE 5.3: AGE WISE DISTRIBUTION OF MALES IN PATIENT GROUP AND REFERENCE GROUP: Age Patient group (n=60) Reference group (n=60) 10-20yrs 6 0 21-30yrs 9 13 31-40yrs 8 8 41-50yrs 6 1 51-60yrs 4 0 61-70yrs 0 0 14 13 12 No. of people 10 9 8 Patient group 8 8 6 6 6 4 Referenc e group 4 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 10-20yrs 21-30yrs 31-40yrs 41-50yrs 51-60yrs 61-70yrs Figure 5.3: Age wise distribution of males in patient group and reference group. 18 TABLE 5.4: AGE WISE DISTRIBUTION OF FEMALES IN PATIENT GROUP AND REFERENCE GROUP: Age Patients group Reference group 10-20yrs 2 9 21-30yrs 9 2 31-40yrs 10 4 41-50yrs 1 1 51-60yrs 5 3 61-70yrs 0 0 12 10 No. of people 10 9 9 Patient group 8 6 5 4 4 Reference group 3 2 2 2 1 1 0 0 0 10-20yrs 21-30yrs 31-40yrs 41-50yrs 51-60yrs 61-70yrs Figure 5.4: Age wise distribution of females in patient group and reference group. People of 21-30yrs (30%) and 31-40yrs (30%) group are the more prone to UCP, in which males of 21-30yrs are 27.27% while females of 31-40yrs are 37.03% with highest rate of UCP. Lowest rate in males was found in age group of 51-60yrs (12.12%), while in females its 41-50yrs (3.70%) (Figure 5.3, 5.4). 19 TABLE 5.5: COMPARISON OF NUMBER OF PEOPLE SMOKING IN No. of people PATIENT GROUP AND REFERENCE GROUP: Males Females Patient group (n=02) 2 0 Reference group (n=03) 3 0 3.5 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 0 0 Females 3 2 Patient group (n=02) Males Reference group (n=03) Figure 5.5: Comparison of number of people smoking in patients and reference group. TABLE 5.6: COMPARISON OF NUMBER OF PEOPLE DRINKING ALCOHOL IN PATIENT GROUP AND REFERENNC GROUP: Males Females Patient group (n=24) 15 9 Reference group (n=12) 9 3 30 No. of people 25 20 9 Females 15 3 10 5 Males 15 9 0 Patient group (n=24) Reference group (n=12) Figure 5.6: Comparison of number of people drinking alcohol in patient group and reference group. 20 TABLE 5.7: COMPARISON OF NUMBER OF PEOPLE WHO SMOKE AND DRINKING ALCOHOL IN PATIENT AND REFERENCE GROUP: Males Females Patient group (n=10) 8 2 Reference group (n=04) 4 0 12 10 2 8 No. of people 6 4 Females 8 0 2 Males 4 0 Patient group (n=10) Reference group (n=04) Figure 5.7: Comparison of number of people who smoke and drinking alcohol in patient group and reference group. Social factors like smoking did not affect UCP but consumption of alcohol is more in patients group (56%) than in referents group (26%). Indeed males consume more amount of alcohol than females (Figure 5.5, 5.6, 5.7). 21 TABLE 5.8: COMPARISON OF PEOPLE HAVING DIABETES IN PATIENT GROUP AND REFERENCE GROUP: Males Females Patient group (n= 4) 2 2 Reference group (n= 3) 3 0 5 4 No. of people 3 2 0 Females 2 Males 3 1 2 0 Patient group (n=4) Reference group (n=3) Figure 5.8: Comparison of people having diabetes in Patient group and Reference group. TABLE 5.9: COMPARISON OF PEOPLE HAVING HYPERTENSION IN No. of people PATIENT GROUP AND REFERENCE GROUP: Males Females Patient group (n=15) 5 10 Reference group (n=8 ) 6 2 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 10 2 Females Males 5 6 Patient group (n=15) Reference group (n=8 ) Figure 5.9: Comparison of people having hypertension in Patient group and Reference group. 22 TABLE 5.10: COMPARISON OF PEOPLE HAVING BOTH DIABETES AND HYPERTENSION IN PATIENT GROUP AND REFERENCE GROUP: Males Females Patient group (n=16 ) 10 6 Reference group (n=8 ) 3 5 18 16 No. of prople 14 12 6 10 Females 8 6 4 5 10 2 Males 3 0 Patient group (n=16 ) Reference group (n=8 ) Figure 5.10: Comparison of people having both diabetes and hypertension in Patient group and Reference group. Incidence of diabetes is same in men and women while incidence of hypertension is 75% in total and is much high in women (66%) suffering with UCP. UCP patients showed more number of diabetes and hypertension cases (26%) than referents (Figure 5.8, 5.9, 5.10) 23 TABLE 5.11: COMPARISON OF SOCIAL AND COMMUNICATION SKILLS BELOW EXPECTATION BETWEEN PATIENT GROUP AND REFERENCE GROUP: Males Females Patients group (n=43 ) 23 20 Reference group (n=15 ) 11 04 50 45 40 No. of people 35 30 20 25 Females 20 Males 15 10 23 4 11 5 0 Patient group (n=43 ) Reference group (n= 15) Figure 5.11: Comparison of social and communication skills below expectation between Patient group and Reference group. Social and communication skills are below expectation in males (53%) than in females (46%) in patients group while 73% males and 26% females are below expectation in referents group. When compared UCP patients have very low levels of social and communication skills than referents (Figure 5.11). 24 TABLE 5.12: COMPARISON OF NUMBER OF PEOPLE HAVING ONLY ANXIETY IN PATIENT GROUP AND REFERENCE GROUP: Males Females Patients group (n= 14) 6 8 Reference group (n= 34) 7 27 No. of people 40 30 Females 27 20 10 Males 8 6 7 Patient group (n= 14) Reference group (n= 34) 0 Figure 5.12: Comparison of number of people having only anxiety in Patient group and Reference group. TABLE 5.13: COMPARISON OF NUMBER OF PEOPLE HAVING ONLY DEPRESSION IN PATIENT GROUP AND REFERENCE GROUP: Males Females Patient group (n=06) 5 1 Reference group (n=07) 6 1 No. of people 8 1 6 1 Females 4 5 2 6 Males 0 Patient group (n=06) Reference group (n=07) Figure 5.13: Comparison of number of people having only depression in Patient group and Reference group. 25 TABLE 5.14: COMPARISON OF NUMBER OF PEOPLE HAVING BOTH ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION IN PATIENT GROUP AND REFERENCE GROUP: Males Females Patient group (n=40) 22 18 Reference group (n= 09) 4 5 50 No. of people 40 30 18 Females 20 10 Males 22 5 4 0 Patient group (n=40) Reference group (n=09 ) Figure 5.14: Comparison of number of people having both anxiety and depression in Patient group and Reference group. In the level of only anxiety, females (29.62%) are having higher ratio when compared to males (18.18%) in UCP patients, they have the same result in referent group. The scores of patients with depression show that the ratio of males (15.15%) is higher than females (3.70%) in both patient as well as referent groups. While people with both anxiety as well as depression the ratios are very high (66%) in both men and women compared to individual risk factors. When compared patients suffering with UCP showed high percentage of anxiety and depression scores (Figure 5.12, 5.13, 5.14). 26 TABLE 5.15: COMPARISON OF PERCENTAGES OF VARIOUS SUBSCALES IN HEALTH RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE (HRQOL) INBETWEEN PATIENT GROUP AND REFERENCE GROUP: Sub-scales Patient group Reference group Physical functioning (%) 31 62 Role physical (%) 52 53 Vitality (%) 49 58 Bodily pain (%) 59 33 General health (%) 33 69 Social functioning (%) 38 66 Role emotional (%) 54 78 Mental health (%) 41 75 Patients group Referents group 90% Sum of the averages 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Figure 5.15: Comparison of percentages of various sub-scales in HealthRelated Quality of Life (HRQOL) in-between Patient group and Reference group. 27 Comparing all the sub-scales of health related quality of life (HRQOL), Physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, social functioning, emotional role and mental health showed a significant difference in patient group and the reference group with a percentage of 31%, 59%, 33%, 38%, 54%, 41% and 62%, 33%, 69%, 66%, 78%, 75% respectively. Physical functioning and general health was very low in patients suffering from UCP and the referents. Physical role and vitality are almost equal in both but emotional role, mental health and social functioning are more in general population than UCP patients. UCP patients suffered with high bodily pains than the referents (Figure 5.15). 28 CHAPTER 6 - SUMMARY: Results from both the qualitative and quantitative analyses showed that the UCP patients were often worried about stress at work, experienced stress at home, and experienced negative life events. Treatment with a double-dose PPI for a period of 2–4 months should be considered in those with GERD- related NCCP. In patients with nutcracker esophagus, GERD should be first excluded by initiating treatment with a potent antireflux medication.10 In patients with non-GERD-related NCCP, smooth muscle relaxants have demonstrated very limited efficacy in ameliorating symptoms. In contrast, pain modulators such as tricyclic antidepressants, trazodone, and SSRIs have become the mainstay of treatment, regardless of the presence or absence of esophageal dysmotility (except achalasia).23 Psychological comorbidity is very common in patients with NCCP and thus should not be overlooked. Pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic approaches have been used with varied success. Future therapy for NCCP will likely include new pain modulators and possibly more potent antireflux medications. Based on the literature in psychology and psychosomatic medicine, three psychosocial factors were proposed to be associated with NCCP. First, NCCP patients were hypothesized to differ from individuals without NCCP in having a unique perceptual style. This hypothesis was derived from two lines of findings that suggest their hypersensitivity to stress and bodily conditions, respectively. Although there were no differences in the number of stressful life events experienced between NCCP subjects and healthy controls, NCCP subjects gave higher negative life-change scores to stressful life events than did their counterparts.20 Psychiatric reviews of somatization 24-27 have emphasized the notion of mind- body connection, but the mechanisms of how psychological and physical factors interact remain unknown. The present results may provide insights to the mind-body connection for NCCP. Psychodynamic28,29 and cognitive-behavioral30-33 theories emphasize the close relationship between the mind (eg, unresolved psychological conflicts, maladaptive cognitions) and feelings of tension. Enhanced tension in the thoracic muscles elicited by anxiety might explain the mechanism of chest pain. This 29 study suggests that one way in which psychological factors may interact with chest pain is through the cognitive pathway. This type of perceptual style predisposes a person to be hypersensitive to normal bodily functioning.34 Monitoring perceptual style is related to high anxiety levels. Because an autonomic and hormonal sequel of anxiety can influence esophageal and cardiac functioning, 35 NCCP patients’ persistent chest pain may be due to their monitoring perceptual style and anxiety associated with this perceptual style. The psychological therapies include: (1) CBT; (2) Relaxation therapy; (3) Hyperventilation control; (4) Hypnotherapy; (5) Other psychotherapy/talking /counseling therapy; (6) Standard care, ’attention’ placebo, waiting list controls, or no intervention as the control conditions. Hypnotherapy has been recently evaluated in the treatment of NCCP patients. Jones and colleagues reported an 80% improvement in symptoms, with a significant reduction in pain intensity, among patients who were receiving 12 sessions of hypnotherapy, compared to only a 23% symptom improvement in the control group. The study concluded that hypnotherapy appears to have a role in treating NCCP and that further studies are needed.36,37 30 CHAPTER 7 - CONCLUSIONS: The pr``esent study is a comparative study using two sample groups namely patient group suffering with UCP and referents group from the general healthy population, 60memebers in each group. Various parameters like stress, communication skills, anxiety, depression as well as health related quality of life are been assessed. The present study concludes that: − A large proportion of those patients who present with acute chest pain to hospital emergency departments have sought healthcare for UCP presentation and that the type of health care professional consulted is influenced by the severity and frequency of reflux symptoms. − High rates of absenteeism from work were reported by those patients with UCP along with considerable interruption to daily activities. − A larger proportion of the UCP patients was immigrant and had a sedentary lifestyle. − Likewise, UCP patients were more often worried about stress at work, perceived more stress at home, more often had sleep problems and had experienced more negative life events than the referents. − Thus UCP patients used cognitive coping strategies in managing stress, but emotional reactions to stress seemed to increase the intensity of the chest pain. − The incident rate of UCP is more in males (55%), than in females (45%). − People of 21-30yrs (30%) and 31-40yrs (30%) group are more prone to UCP, in which highest rate occurred in males of 21-30yrs (27.27%) and in females of 3140yrs (37.03%). − Social and communication skills are below expectation in males (53%) than in females (46%) in patients group, while 73% males and 26% females are below expectation in referents group. − Patients showed atleast one stress factor in their life. − Risk of occurrence of UCP is more in people having both anxiety and depression than individual components. This had a significant effect on their daily life. 31 − The ratio of people with both anxiety as well as depression is very high in patient group (70%) than the reference group (15%) compared to individual risk factors. − In comparison with a random population sample, most the sub-scales of health related quality of life (HRQOL) like Physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, social functioning, emotional role and mental health showed a significant difference in patient group. 32 CHAPTER 8 - LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS: 8.1 LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY Sample size was low; Duration of the study 6months was insufficient to gather the required outcomes; We couldn’t follow few UCP cases as the occurrence was more during night times; Lack of time to interact fully as most of the cases are reported in the outpatient department. Our study was not an interventional study. 8.2 FUTURE DIRECTIONS These should Include a larger number of participants with explicit sample size and power analysis; Have follow-up periods of atleast 12 months and preferably longer; Further RCTs of psychological interventions for UCP are needed; Use interventions that are explicitly described manualised and monitored for treatment accuracy. 33 CHAPTER 9 – BIBLIOGRAPHY 1 Fass R, Malagon I, Schmulson M, Chronic Chest Pain - Chest pain of esophageal origin. Curr Opin Gastroenterol Vol 17, 2001. 2 Sami R. Achem, MD, FACP, FACG, AGAF. Noncardiac Chest Pain Treatment Approaches, American College of Gastroenterology 2002. 3 Annika Janson Fagring, Karin I Kjellgren, Annika Rosengren, Lauren Lissner, Karin Manhem and Catharina Welin, Depression, anxiety, stress, social interaction and health-related quality of life in men and women with unexplained chest pain, BMC Public Health Vol 8, Issue 165, 2008. 4 Lynette Spalding MB BS, Emma Reay MB BS, Clive Kelly MD FRCP, Cause and outcome of atypical chest pain in patients admitted to hospital, Journal Of The Royal Society Of Medicine Volume 96, march 2003. 5 J. Chambers and C. Bass, Atypical chest pain: looking beyond the heart, Q J Med Vol 91, 1998, Pg.239–244. 6 Kisely SR, Campbell LA, Yelland MJ, Paydar A, Psychological interventions for symptomatic management of non-specific chest pain in patients with normal coronary anatomy (Review), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 6. 7 Philip O. Katz, M.D., and Donald O. Castell, M.D, Approach to the Patient With Unexplained Chest Pain, The American Journal Of Gastroenterology Vol. 95, No. 8, Suppl., 2000. 8 K Y Ho, J Y Kang, B Yeo, W L Ng, Non-cardiac, non-oesophageal chest pain: the relevance of psychological factor, Gut Vol 42, 1998, Pg.105–110. 9 DeMeester TR, O’Sullivan GC, Bermudez G, Midell AI, Cimochowski GE, O’Drobinak J. Esophageal function in patients with angina-type chest pain and normal coronary angiograms. Ann Surg Vol 196, 1982; Pg.488–98. 10 Achem SR, Kolts BE, MacMath T, Richter J, Mohr D, Burton L, Castell DO, Effects of omeprazole versus placebo in treatment of noncardiac chest pain and gastroesophageal reflux, Dig Dis Sci Vol 42, 1997, Pg.2138–45. 11 Chambers J, Cooke R, Anggiansah A, Owen W. Effect of omeprazole in patients with chest pain and normal coronary anatomy: initial experience. 34 International Association for the Study of Pain, Int J Cardiol Vol 65, 1998, Pg.51–5. 12 Cannon RO 3rd, Quyyumi AA, Mincemoyer R, Stine AM, Gracely RH, Smith WB, Geraci MF, Black BC, Uhde TW, Waclawiw MA, et al. Imipramine in patients with chest pain despite normal coronary angiograms. N Engl J Med Vol 330, 1994; Pg.1411–7. 13 Prakash C, Clouse RE. Long-term outcome from tricyclic antidepressant treatment of functional chest pain. Dig Dis Sci Vol 44, 1999, Pg.2373–9. 14 Varia I, Logue E, O’Connor C, Newby K, Wagner HR, Davenport C, Rathey K, Krishnan KR. Randomized trial of sertraline in patients with unexplained chest pain of noncardiac origin. Am Heart J Vol 140, 2000, Pg.367–72. 15 Spinhoven P, Van der Does AJ, Van Dijk E, Van Rood YR. Heart-focused anxiety as a mediating variable in the treatment of noncardiac chest pain by cognitive-behavioral therapy and paroxetine. J Psychosom Res Vol 69, 2010, Pg.227–35. 16 Lee H, Kim JH, Min BH, Lee JH, Son HJ, Kim JJ, Rhee JC, Suh YJ, Kim S, Rhee PL. Efficacy of venlafaxine for symptomatic relief in young adult patients with functional chest pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled, crossover trial. Am J Gastroenterol Vol 105, 2010, Pg.1504-12. 17 Jones H, Cooper P, Miller V, Brooks N, Whorwell PJ. Treatment of noncardiac chest pain: a controlled trial of hypnotherapy. Gut Vol 55, 2006, Pg.1403–8. 18 G. D. Eslick, & N. J. Talley, Non-cardiac chest pain: predictors of health care seeking, the types of health care professional consulted, work absenteeism and interruption of daily activities, Aliment Pharmacol Ther Vol 20, 2004, Pg.909–915. 19 Lynette Spalding MB BS Emma Reay MB BS Clive Kelly MD FRCP, Cause and outcome of atypical chest pain in patients admitted to hospital, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, Volume 96, March 2003. 20 Cecilia Cheng, Wai-man Wong, Kam-chuen lai, Benjamin Chun-yu Wong, Wayne hc hu, Wai-mo hui, and Shiu-kum lam, Psychosocial Factors in Patients With Noncardiac Chest Pain, Psychosomatic Medicine Vol 65, 2003, Pg.443–449. 35 21 Steve R Kisely1, Leslie Anne Campbell, Michael J Yelland, Anita Paydar, Psychological interventions for symptomatic management of non-specific chest pain in patients with normal coronary anatomy, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 6, 2012. 22 J Mant, RJ McManus, RAL Oakes, BC Delaney, PM Barton, JJ Deeks, L Hammersley, RC Davies, MK Davies and FDR Hobbs, Systematic review and modelling of the investigation of acute and chronic chest pain presenting in primary care, Health Technology Assessment Vol. 8, 2004, No. 2 23 Ron Schey, MD, Autumn Villarreal, MS, and Ronnie Fass, MD, FACP, FACG, Noncardiac Chest Pain: Current Treatment, Gastroenterology & Hepatology Volume 3, Issue 4 April 2007. 24 von Scheel C, Nordgren L. The mind-body problem in medicine. Lancet Vol 1, 1986, Pg.258–61. 25 Mora G. Mind-body concepts in the Middle Ages. Part I. J Hist Behav Sci Vol 14, 1978, Pg.344–61. 26 Mora G. Mind-body concepts in the Middle Ages. Part II. The Moslem influence, the great theological systems, and cultural attitudes toward the mentally ill in the late middle Ages. J Hist Behav Sci Vol 16, 1980, Pg.58–72. 27 Katon W, Hall ML, Russo J, Cormier L, Hollifield M, Vitaliano PP, Beitman BD. Chest pain: relationship of psychiatric illness to coronary arteriographic results. Am J Med Vol 84, 1988, Pg.1–9. 28 Mayou R. Illness behavior and psychiatry. Gen Hosp Psychiatric Vol 11, 1989; Pg.307–12. 29 Mayou R. Invited review: atypical chest pain. J Psychosom Res Vol 33, 1989, Pg.393–406. 30 Thompson LW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and treatment for late-life depression. J Clin Psychiatry Vol 57, 1996, Pg.29–37. 31 Roth DA, Heimberg RG. Cognitive-behavioral models of social anxiety disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am Vol 24, 2001, Pg.753–71. 32 Rapee RM, Heimberg RG. A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behav Res Ther Vol 35, 1997, Pg.741–56. 33 Shafran R, Tallis F. Obsessive-compulsive hoarding: A cognitive-behavioral approach. Beh Cog Psychother Vol 24, 1996, Pg.209–21. 36 34 Tyrer P. The role of bodily feelings in anxiety. London (England): Oxford University Press 1976. 35 Clark DM. A cognitive approach to panic. Behav Res Ther Vol 24, 1986, Pg.461–70. 36 Jones H, Cooper P, Miller V, et al. Treatment of noncardiac chest pain: a controlled trial of hypnotherapy. Gut.Vol 55, 2006, Pg.1403-1408. 37 O S Palsson, W E Whitehead, Noncardiac Chest Pain: Current Treatment, Gut Vol 55, 2006, Pg.1381–1384. 38 Cheng C, Hui W, Lam S. Perceptual style and behavioral pattern of individuals with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Health Psychol Vol 19, 2000, Pg.146–54. 39 Jerlock, M., Gaston-Johansson, F. & Danielson, Living with unexplained chest pain. Journal of Clinical Nursing Vol 14(8), 2005, Pg. 956-964. 40 Jerlock, M., Welin, C., Rosengren, A. & Gaston-Johansson, Pain characteristics in patients with unexplained chest pain and patients with ischemic heart disease, European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing Vol 6(2), 2007, Pg.130-136. 41 Jerlock, M., Gaston-Johansson, F., Kjellgren, K. I., & Welin, Coping strategies, stress, physical activity and sleep in patients with unexplained chest pain. BMC Nursing, Vol 5 (7), 2006. 42 Jerlock, M., Kjellgren, K. I., Gaston-Johansson, F., Lissner, L., Manhem, K., Rosengren, A., & Welin, C. Psychosocial profile in men and women with unexplained chest pain: A case-control study. (Submitted for publication) 43 G. D. Eslick, D. S. Coulshed & N. J. Talley, Review article: the burden of illness of non-cardiac chest pain, Aliment Pharmacol Ther Vol 16, 2002, Pg.1217–1223. 44 Cheng C, Hui W, Lam S. Coping style of individuals with functional dyspepsia. Psychosom Med Vol 61, 1999, Pg.789–95. 45 Katon W, Hall ML, Russo J, Cormier L, Hollifield M, Vitaliano PP, Beitman BD. Chest pain: relationship of psychiatric illness to coronary arteriographic results. Am J Med Vol 84, 1988, Pg.1–9. 46 Mora G. Mind-body concepts in the Middle Ages. Part I. J Hist Behav Sci Vol 14, 1978;, Pg.344–61. 37 47 Mora G. Mind-body concepts in the Middle Ages. Part II. The Moslem influence, the great theological systems, and cultural attitudes toward the mentally ill in the late middle Ages. J Hist Behav Sci Vol 16, 1980, Pg.58–72. 48 Ron Schey, MD, Autumn Villarreal, MS, and Ronnie Fass, MD, FACP, FACG, Noncardiac Chest Pain: Current Treatment, Gastroenterology & Hepatology Vol 3, Issue 4, April 2007. 49 Van Peski-Oosterbaan A, Spinhoven P, van Rood Y, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for noncardiac chest pain: a randomized trial. Am J Med. Vol 106, 1999, Pg.424-429. 50 Kisely S, Guthrie E, Creed FH, Tew R. Predictors of mortality and morbidity following admission with chest pain, Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London Vol 31, 1997, Pg.177–83. 51 H Jones, P Cooper, V Miller, N Brooks, P J Whorwell, Treatment of noncardiac chest pain: a controlled trial of hypnotherapy, Gut Vol 55, 2006, Pg.1403–1408. 52 Achem SR, Kolts BE, Wears R, et al. Chest pain associated with nutcracker esophagus: a preliminary study of the role of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol Vol 88, 1993, Pg.187-192. 53 G. D. Eslick, M. P. Jones, Non-cardiac chest pain: prevalence, risk factors, impact and consulting — a population-based study, Aliment Pharmacol Ther Vol 17, 2003, Pg.1115–1124. 54 B. Delia Johnson, Leslee J. Shaw, Carl J. Pepine, Steven E. Reis, Sheryl F. Kelsey1, George Sopko, William J. Rogers, Sunil Mankad, Barry L. Sharaf, Vera Bittner, and C. Noel Bairey Merz, Persistent chest pain predicts cardiovascular events in women without obstructive coronary artery disease: results from the NIH-NHLBI-sponsored Women’s Ischaemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study, European Heart Journal Vol 27, 2006, Pg.1408– 1415. 55 Lee H, Kim JH, Min BH, Lee JH, Son HJ, Kim JJ, Rhee JC, Suh YJ, Kim S, Rhee PL. Efficacy of venlafaxine for symptomatic relief in young adult patients with functional chest pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled, crossover trial. Am J Gastroenterol Vol 105, 2010, Pg.1504–12. 38 56 Wielgosz AT, Fletcher RH, McCants CB, McKinnis RA, Haney TL, Williams RB. Unimproved chest pain in patients with minimal or no coronary disease: a behavioral phenomenon. Am Heart J Vol 108, 1984, Pg.67–72. 39 CHAPTER 10 - ANNEXURES: PATIENT CONSENT FORM I have read/ been briefed on “Investigating the effect of psychosocial risk factors on non-cardiac chest pain” and I voluntarily agree to participate in the project. I understand that participation in this study may or may not benefit me. Its general purpose, potential benefits and inconveniences have been explained to me up to my satisfaction. I have the option to withdraw from the study at any stage. I hereby give my consent for this study. Name of the patient: Impression Date: Signature/ Thumb 40 PATIENT DATA COLLECTION FORM DEMOGRAPHIC DETAILS: Name: Height: Weight: Age/gender: Date: BMI: OP/ IP: Department: Consultant Dr: Contact no: Address: Marital status: Single/ Married (or) cohabitating/ divorced/ widower. Education: Primary/ Secondary school/ University. Work Status: Employed (full time/ part time)/ early retirement/ disability pension/ retired/ unemployed. Immigrant status: Local/ non-local. Physical activity in leisure time: 1) Sedentary in leisure time. 2) Moderate exercise in leisure time (walking, riding bicycle, light gardening). 3) Regular exercise and training (strenuous activity for a minimum of 3hrs/week). 4) Intense training or competitive sport. Physician conformed diabetes: YES/ NO Physician conformed hypertension: YES/ NO Current smoker: YES/ NO Alcohol consumption: YES/ NO month. C/O: Ex-Smoker: YES/ NO Frequency/ amount each day-week- 41 PREVIOUS MEDICAL HISTORY: PREVIOUS MEDICATION HISTORY: PHYSICAL EXAMINATION: VITALS: Previous stress at work: 1) Never perceived stress. 2) Some period of stress. 3) Some period of stress during last 5yrs. 4) Several periods of stress during last 5yrs. 5) Permanent stress during the last 1 year. 6) Permanent stress during the last 5yrs. Perception of their marriage or cohabitation: I] “How do you perceive your marriage or cohabitation?” 1) Very happy. 2) Fairly happy. 3) Difficult to say. 4) Rather unhappy. 5) Very unhappy. II] “How often do you have difficulty getting along with your wife or husband or cohabitant?” 42 1) Never. 2) Seldom. 3) Sometimes. 4) Very often. 5) Almost all the time. LAB INVESTIGAGTIONS: Rx: 43 SOCIAL INTERACTION AND COMMUNICATION SKILLS CHECKLIST: Please rate the items on the following scale: 1 = Not able to perform even with assistance 2 = Able to perform with two or more verbal prompts 3 = Able to perform with less than two verbal prompts 4 = Able to perform with minimal assistance (Gesture) 5 = Able to perform independently 1. Respond when called by name.............................1..........2..........3..........4..........5 2. Follow verbal instructions in 1:1 setting..............1..........2..........3..........4..........5 3. Follow verbal instructions in small group............1..........2..........3..........4..........5 4. Appropriately gain attention from others.............1..........2..........3..........4..........5 5. Ability to take turns in conversation....................1..........2..........3..........4..........5 6. Ability to initiate conversation.............................1..........2..........3..........4..........5 7. Respond appropriately to praise...........................1..........2..........3..........4..........5 8. Ability to accept supervision ...............................1..........2..........3..........4..........5 9. Recognize and respond to non-verbal cues .........1..........2..........3..........4..........5 10. Give simple instructions to others ..................1..........2..........3..........4..........5 11. Ability to consistently communicate needs/wants..1..........2..........3..........4..........5 12. Ability to solve basic social problems ..............1..........2..........3..........4..........5 13. Ability to ask for help/assistance ......................1..........2..........3..........4..........5 44 14. Ability to follow simple visual instructions ......1..........2..........3..........4..........5 15. Ability to work as part of a team .......................1..........2..........3..........4..........5 16. Ability to express lack of understanding or ask questions when appropriate …………………………………………...................1..........2..........3..........4..........5 17. Ability to request a break when needed ............1..........2..........3..........4..........5 18. Respond appropriately to criticism/correction.....1..........2..........3..........4..........5 19. Follow social cues in a group ..............................1..........2..........3..........4..........5 20. Ability to learn a task through modeling …..........1..........2..........3..........4..........5 TOTAL SCORE = _____ Reference: >90 – social interaction skills exceed expectations. 70-89 - social interaction skills meet expectations. 50-69 - social interaction skills substandard to expectations. 30-49 - social interaction skills below expectations. <29 - social interaction skills far below expectations. 45 ZUNG SELF-RATING DEPRESSION SCALE Please read each statement and decide how much of the time the statement describes how you have been feeling during the past several days. Make check mark (✓) in appropriate column. 1. I feel down-hearted and blue A little of Some of Good Most of the time the time part the time 1 2 Morning is when I feel the best I have crying spells or feel like it I have trouble sleeping at night I eat as much as I used to 4 1 1 4 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. I still enjoy sex I notice that I am losing weight I have trouble with constipation My heart beats faster than usual I get tired for no reason My mind is as clear as it used to be 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 2. 3. 4. 5. 4 3 2 2 3 of the3 time 2 3 3 2 4 1 1 1 1 4 3 2 2 2 2 3 2 3 3 3 3 2 1 4 4 4 4 1 I find it easy to do the things I used to I am restless and can’t keep still I feel hopeful about the future I am more irritable than usual I find it easy to make decisions I feel that I am useful and needed My life is pretty full I feel that others would be better 4 1 4 1 4 4 4 3 2 3 2 3 3 3 2 3 2 3 2 2 2 1 4 1 4 1 1 1 off if I were dead 1 2 3 4 4 3 2 1 20. I still enjoy the things I used to do TOTAL SCORE =__________ 1 4 4 1 46 Reference: 20-44 – Normal Range 45 – 59 – Mildly depressed 60 – 69 – Moderately depressed ≥70 – Severely depressed. 47 TRAIT ANXIETY SCALE Please rate the items on the following scale: 1-almost never; 2- sometimes; 3- often; 4- almost always. 1) I fell pleasant…………………………………………..…..1…..2…..3…..4 2) I feel nervous and restless……………………………...….1…..2…..3…..4 3) I feel satisfied with myself…………………………………1…..2…..3…..4 4) I wish I could be as others seem to be……………….…….1…..2…..3…..4 5) I feel like a failure…………………………..…………...…1…..2…..3…..4 6) I feel rested……………………………………………...…..1…..2…..3…..4 7) I am “calm, cool and collected”………………………..….. 1…..2…..3…..4 8) I feel that difficulties are piling up so that I cannot overcome them..1..2..3..4 9) I worry too much over something that really doesn’t matter….1….2….3....4 10) I am happy………………………………………………..…1…..2…..3…..4 11) I have disturbing thoughts………………………….………1…..2…..3…..4 12) I lack self-confidence………………………………………..1…..2…..3…..4 13) I feel secure……………………………………..………..…1…..2…..3…..4 14) I make decisions easily…………………………….……….1…..2…..3…..4 15) I feel inadequate………………………………………..…..1…..2…..3…..4 16) I am content…………………………………………..…….1…..2…..3…..4 17) Some unimportant thoughts runs through my mind and bothers me………………………………………………………….1…..2…..3…..4 18) I take disappointments so keenly that I can’t put them out of my mind ……………………………………………………….……1…..2…..3…..4 48 19) I am a steady person………………………………………1…..2…..3…..4 20) I get in a state of tension or turmoil as I think over my recent concerns and interests…………………………………………………….1…..2…..3…..4 TOTAL SCORE =__________ Reference: 20 – 44 – Normal. 45 – 59 – Mild. 60 – 69 – Moderate. ≥70 – sever. 49 SF-36 HEALTH SURVEY: 1. In general, would you say your health is: □ Excellent 2. □ Very good □ Good □ Fair □Poor Compared to one year ago, how would you rate your health in general now? □ Much better now than a year ago □ Somewhat better now than a year ago □ About the same as one year ago □ Somewhat worse now than one year ago □ Much worse now than one year ago 3. The following items are about activities you might do during a typical day. Does your health now limit you in these activities? If so, how much? a. Vigorous activities, such as running, lifting heavy objects, participating in strenuous sports. □ Yes, limited a lot. b. Moderate □ Yes, limited a little. □No, not limited at all. activities, such as moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling, or playing golf? □ Yes, limited a lot. c. Lifting or carrying groceries. □ Yes, limited a lot. d. Climbing e. Climbing □ Yes, limited a little. □No, not limited at all. □ Yes, limited a little. □No, not limited at all. □ Yes, limited a little. □No, not limited at all. □ Yes, limited a little. □No, not limited at all. □ Yes, limited a little. □No, not limited at all. several blocks. □ Yes, limited a lot. i. Walking □No, not limited at all. more than one mile. □ Yes, limited a lot. h. Walking □ Yes, limited a little. kneeling or stooping. □ Yes, limited a lot. g. Walking □No, not limited at all. one flight of stairs. □ Yes, limited a lot. f. Bending, □ Yes, limited a little. several flights of stairs. □ Yes, limited a lot. one block. □ Yes, limited a lot. j. Bathing □ Yes, limited a little. □No, not limited at all. or dressing yourself. □ Yes, limited a lot. □ Yes, limited a little. □No, not limited at all. 50 4. During the past 4 weeks, have you had any of the following problems with your work or other regular daily activities as a result of your physical health? a. Cut down the amount of time you spent on work or other activities? Yes b. Accomplished less than you would like? c. Were limited in the kind of work or other activities d. Had difficulty performing the work or other activities (for example, it took extra time) 5. During Yes Yes No No Yes No No the past 4 weeks, have you had any of the following problems with your work or other regular daily activities as a result of any emotional problems (such as feeling depressed or anxious)? a. Cut down the amount of time you spent on work or other activities? Yes No b. Accomplished less than you would like c. Yes No Didn't do work or other activities as carefully as usual 6. During Yes No the past 4 weeks, to what extent has your physical health or emotional problems interfered with your normal social activities with family, friends, neighbors, or groups? □ Not at all 7. How □ slightly □ moderately □ Quite a bit □ extremely much bodily pain have you had during the past 4 weeks? □ Not at all 8. During □ slightly □ moderately □ Quite a bit □ extremely the past 4 weeks, how much did pain interfere with your normal work (including both work outside the home and housework)? □ Not at all 9. These □ slightly □ moderately □ Quite a bit □ extremely questions are about how you feel and how things have been with you during the past 4 weeks. For each question, please give the one answer that comes closest to the way you have been feeling. How much of the time during the past 4 weeks. a. Did you feel full of pep? □ All of the time □ Most of the time □A good bit of the time □ Some of the time □ A little of the time □ None of the time a. Have you been a very nervous person? 51 □ All of the time □ Most of the time □A good bit of the time □ Some of the time □ A little of the time □ None of the time b. Have c. □ All of the time □ Most of the time □A good bit of the time □ Some of the time □ A little of the time □ None of the time Have you felt calm and peaceful? □ All of the time □ Most of the time □A good bit of the time □ Some of the time □ A little of the time □ None of the time d. Did you have a lot of energy? □ All of the time □ Most of the time □A good bit of the time □ Some of the time □ A little of the time □ None of the time e.Have f. you felt so down in the dumps nothing could cheer you up? you felt downhearted and blue? □ All of the time □ Most of the time □A good bit of the time □ Some of the time □ A little of the time □ None of the time □ All of the time □ Most of the time □A good bit of the time □ Some of the time □ A little of the time □ None of the time Did you feel worn out? g. Have h. 10. . you been a happy person? □ All of the time □ Most of the time □A good bit of the time □ Some of the time □ A little of the time □ None of the time □ All of the time □ Most of the time □A good bit of the time □ Some of the time □ A little of the time □ None of the time Did you feel tired? During the past 4 weeks, how much of the time has your physical health or emotional problems interfered with your social activities (like visiting friends, relatives, etc.)? 11. . □ All of the time □ Most of the time □ A little of the time □ None of the time □ Some of the time How TRUE or FALSE is each of the following statements for you? 52 a. I b. I seem to get sick a little easier than other people □ Definitely true □ Mostly true □ Mostly false □ Definitely false am as healthy as anybody I know □ Definitely true □ Mostly false c. I □ Don't know □ Mostly true □ Don't know □ Definitely false expect my health to get worse □ Definitely true □ Mostly true □ Mostly false □ Definitely false d. My health □ Don't know is excellent □ Definitely true □ Mostly true □ Mostly false □ Definitely false TOTAL SCORE =__________ □ Don't know