Project Summary - Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service

The Social Psychology of Prepaid Monetary Incentives in Surveys:

Field and Lab Experiments

Table of Contents

Overview

This proposal seeks funding for our collaborative work using experiments with survey incentives to increase our understanding of the psychological mechanisms —as well as social and cultural factors—that determine the efficacy of incentives in promoting participation in sample surveys. Our work is interdisciplinary and synergistic in that it draws from separate but related literatures and research traditions in survey methodology, sociology, and social psychology.

The research problem: Ascertain the psychological mechanisms that underlie the positive effect of prepaid monetary incentives on rates of response to sample survey invitations.

● Sample surveys are a key feature of data-driven research and decision-making in all sectors of contemporary society, but as survey response rates continue to decline it is increasingly important to learn what causes members of the general population to respond to survey invitations.

● The positive effect of token monetary prepaid incentives on survey response rates is well known and documented in many different survey contexts.

● Yet, the psychology underlying this behavioral effect has mostly been a matter of theoretical exploration in the absence of specific empirical evidence.

● Our understanding of how survey incentives work to increase response rates can be substantially improved by applying developed concepts and measures from psychology to find out how, why, and on whom different types of survey incentives operate. We propose to test specific hypotheses about the underlying psychology by means of carefully designed experiments in the lab and in the field.

Our approach is distinctive in three respects that are relevant to the scientific merit of the work:

● We bring together existing theory and research on survey incentives (from the survey methodology literature) with conceptual tools and research results on how obligation and indebtedness operate in other contexts (from the psychology literature).

● We propose to use instruments we are developing that directly measure key aspects of the sample member’s perception of the survey and the survey request (with or without an incentive), such as obligation, indebtedness, guilt, gratitude, trust, perception of legitimacy, perception of im-

1

portance, and (where applicable) perception of the monetary incentive itself. Our recently completed pilot tests in the lab and in the field support the validity and usability of these measures.

● We will use both field and laboratory experiments to uncover the ways in which prepaid incentives and contingent in centives affect the sample member’s experience of the survey request and thereby increase (or fail to increase) the likelihood of survey participation. o One of the main limitations of the previous research on survey incentives is that researchers have had no way of knowing why some participants did not respond to a survey request. The unique feature of our proposal is that our lab experiments will allow us to compare and contrast how sample members, including both (eventual) respondents and non-respondents, experienced the survey request (e.g., how grateful, indebted, happy etc. they felt at that time of the survey request). In other words, we will be able to test, for the first time, whether psychological reactions at the time of the survey invitation predict survey participation later. This will help us understand why some individuals do not respond to the survey request, as well as why a prepaid monetary incentive increases survey responses. o The field experiments (using mixed-mode surveys to households sampled from a highly diverse metropolitan area) will allow us to compare perceptions of the survey among respondents who were offered incentives of various types to those who were not. They will also assess key moderators of survey perceptions and the incentive effect on participation (e.g., race, community attachment, socioeconomic status). Field experiments also give us evidence of the external validity of our findings across a wider range of sample members.

Theoretical background

Incentives research. Survey researchers have a long history of continuous methodological experimentation (Nock and Guterbock, 2010). A successful series of trials and experiments in the design of mail-out questionnaires was highlighted by a young Don Dillman in the first edition of his book introducing what he then called the “Total Design Method” (Dillman, 1978). Heberlein and Baumgartner (1978) published a regression analysis of a wide range of factors governing response rates for mail surveys, and Fox, Crask and Kim (1988) applied the new methods of meta-analysis to identify significant effects using data from

82 published mail-out experiment reports, including 30 incentive experiments (see also Yammarino, et al.,

1991). There have been numerous studies focused on the effect of incentives. Armstrong (1975) used

18 prior studies to model the effect of incentive amounts on response rates. Church’s meta-analysis

(1993) looked at 34 experiments on incentives, showing that prepaid monetary incentives, sent unconditionally with the survey invitation, have a strong effect on response rates (raising the rate by 19 percentage points on average), while conditional incentives, sent in return for survey completion, have no significant effect. This was not a new finding: a 1940 experiment by Hancock yielded a 47% response rate when respondents were given 25 cents in the invitation, compared to 18% when 25 cents was promised conditional on completion. James and Bolstein (1990, 1992) showed, 50 years later, that a prepaid incentive as small as 25 cents significantly boosts response rates (and higher amounts boost the rate more) while a promised incentive of $50 fails to do so. As Trussell and Lavrakas (2004, p. 353) state: “The literature is virtually unanimous in the conclusion that the use of small, noncontingent monetary incentives will increase cooperation rates in mailed surveys and are more effective than a promised reward, even if the promised reward is of greater value, for completing the survey.”

Social exchange. Dillman (1978) provided a convincing theoretical explanation of this pattern, later expanded (Dillman, Smyth and Christian 2014, ch.2). The process of sending someone a questionnaire and getting them to complete it can be viewed as a special case of social exchange.

Social exchange is distinguished from economic exchange in that it creates future obligations that are diffuse and unspecified, the nature of the return is left to the discretion of the one who owes it, and the range of things exchanged is potentially very bro ad. As explained in Avdeyeva and Matland’s (2013, p. 175) report on a recent incentive experiment, funded by NSF and fielded in Siberia: “[C]onditional monetary rewards

2

invoke an economic exchange model in the interaction between the surveyor and survey participant. In an economic exchange respondents view a promised reward as financial remuneration for completing a survey; thus it is culturally acceptable not to respond if they do not believe the reward compensates them sufficiently for their time and effort, or if they are uninterested in the topic. … From this perspective an unconditional monetary reward sent with a questionnaire and a request to participate in a survey generates a social exchange. Unconditionally provided rewards encourage respondents to reciprocate by completing a survey because the respondent feels an obligation to respond to an unusual and unexpected positive gesture.’’

While this explanation is straightforward and compelling, it is neither fully supported by direct empirical evidence nor is it complete. Nearly all of the research studies cited above involve experiments in which survey features (e.g., type of incentives, invitation letters) are manipulated and resulting response rates are evaluated. We know, then, what will raise response rates. From this traditional research design, however, we know little or nothing about the underlying psychological mechanisms. Just why did some people respond, while others did not? Researchers have offered plausible post hoc speculations involving psychological mechanisms, but they have not attempted to observe or measure the actual perceptions or psychological states of the sample member. As Singer and Ye point out, “there is no research on whether the respondent [offered a prepaid incentive] a ctually feels the obligation to respond”

(2011, p. 115). Of course, even less is known about the psychology of non-respondents, since researchers typically have data only on respondents (although some limited inferences can be made in studies when a rich sampling frame is available [e.g. Avadyeva and Maitland 2013]). The research we propose here aims to correct these deficiencies.

We do not dispute the idea that a prepaid incentive creates a sense of obligation and indebtedness in the recipient —in fact, we have pilot data that shows precisely that, perhaps for the first time. But the focus on indebtedness alone overlooks several key ideas in the social exchange perspective, many of which have been articulated by Dillman. The social exchange perspective has its origins in anthropology, sociology, and social psychology, where theorists saw the exchange of things like goods, services, mates, gifts, information and esteem as constitutive of the social structure itself (Homans 1961, Blau 1964, Thibaut &

Kelley 1959, Levi-Strauss 1965). A system of transactions builds relationships and social structures. A prepaid monetary incentive is a gift , and gifts have extraordinary symbolic power. Theorists such as

Mauss (1954) and Schwartz (1967) have written about their manifold effects and their significance. The bestowal of a gift is not merely a transaction, not just one additional “benefit” in a mental benefit-cost equation, but an act that conveys meanings to the recipient about the giver and thereby helps to define the relationship between giver and receiver. Dillman recognized, from the first, that “the decision to respond is based on an overall, subjective evaluation of all the study elements visible to the prospective respondent . . . Each element contribu tes to the overall image of the study” (1978, p. 8). This holistic view leads to one of our main points of theoretical departure: prepaid incentives do more than create indebtedness . They have the potential to alter the sample member’s perception of several elements that affect the decision to participate. Among these are trust in the requesting party, the sample member’s sense of the importance of the survey, the perception of the burden of responding, and the sample member’s sense of being appreciated, respected, and treated as an equal. To put the same idea in terms of Cialdini’s theory of persuasion (1984), prepaid incentives do not merely invoke the norm of reciprocity, but can also favorably alter the sample member’s perception of the requestor’s likability and authority (thus affecting three of Cialdini’s six principles). In terms of Dillman’s “tailored design method,” incentives do not merely affect the perceived benefit of the survey, but affect perceived costs (risks) and help to generate the crucial element of trust. In terms of Singer’s overall “benefit-cost” theory of survey participation (2011), prepaid incentives can actually alter the sample member’s assessment of a range of benefits and costs relevant to the decision to participate.

With respect to the perception of trust, Dillman (1978, p. 16) was explicit: “The reason that token financial incentives have been found so effective in mail questionnaire research may lie not in their monetary value, but rather in the fact that they are a sym bol of trust. They represent the researcher’s trust that the

3

respondent will accept an offer made in good faith. Second, incentives may stimulate the belief on the part of the respondent that future promises . . . will be carried out.” In the 2014 version (p, 40), he adds that “sending of such an incentive with the request to respond represents a behavioral commitment on the part of the surveyor . . .[which] provides a means of reducing the uncertainty of benefits based upon reciprocity” (cf. Molm, Takahashi & Peterson 2000). Yet this simple idea seems to have been lost in later research. Avdayeva and Matland (2013) discuss the lack of interpersonal trust in Russia as a background factor that could make incentives ineffective, yet they overlook the possible effect of incentives upon that trust. They report significant findings regarding trust (p. 187-9). One of their samples was a group of participants in an earlier study that included measurement of social trust. Using this rich frame, the researchers found higher levels of trust among those who responded to the prepaid incentive

(compared to non-respondents in the same treatment), while those who responded in the contingent incentive treatment had lower levels of trust. They dismiss these results as random noise. But the higher level of trust might well be an effect of the prepaid incentive itself. (An alternative explanation, which will be taken up below, is that obligation in response to the incentive might work more strongly on those who are trusting.)

Obligation, indebtedness, and gratitude as variable responses. Our second major point of theoretical departure is to take seriously the idea that obligation and indebtedness are not immutable givens in social exchange, but vary according to situatio ns, social and cultural factors as well as individuals’ psychological states. Yammarino et al. (1991, p. 62324) found “split” effects for monetary incentives, depending on the type of survey population. There are few works in sociology that study obligation systematically (but see

Nock, Kingston & Holian 2008). However, recent work in social psychology has begun seriously to examine the different psychological states that reciprocity can generate: obligation, indebtedness and gratitude. Indebtedness is an interpersonal emotion that is experienced when someone does something special for someone else at a significant cost (Greenberg & Westscott, 1983; Hitokoto, Niiya, & Tanaka-

Matsumi, 2008; Watkins, Scheer, Ovnicek, & Kolts, 2006). Gratitude is very similar to indebtedness in the sense that it is also experienced when someone does something special for someone else (Algoe, 2012).

However, whereas gratitude does not typically suggest a payback, indebtedness does. After all, it is the feeling of owing a debt. A prepaid payment is done for respondents to complete a survey later. In the context of survey participation, repayment could be easily done in the form of completing the survey.

Thus, a prepaid payment might induce a sense of indebtedness, which in turn might increase the likelihood of completing a survey later. Indebtedness, or feeling obliged to repay, is generally an aversive state itself, and it could further generate a sense of guilt if an actor fails to repay. Because it is an aversive emotional state, people generally try to avoid the feeling of indebtedness (Mattews & Shook,

2013; Shen, Wan, & Wyer, 2011). When indebted, people try to repay quickly so that they no longer feel indebted.

Previous research (e.g., Greenberg & Westscott, 1983; Shen et al., 2011) suggests that indebtedness leads more to material repayment than it does to continuation of the relationship. A recent study found that indebtedness toward their recommendation letter writers at the time of college applications predicted whether students later gave a thank-you gift to their letter writers (mostly their high school teachers, Oishi,

Lee, & Koo, 2015). Interestingly, however, indebtedness did not predict whether students were still in touch with the letter writers. A thank-you gift should result in a sense of closure with regard to the feeling of indebtedness because it signals that the debt has been repaid. In other words, indebtedness by definition implies that the relationship should continue until repayment is made (to be sure, in some relationships debts are so large that the repayment might never end), and thus feelings of indebtedness should predict repayment (e.g., thank-you gifts, survey completion).

In contrast, gratitude is an emotion that reflects the intention to bond and bind (Algoe, 2012; Algoe, Haidt,

& Gable, 2008; Emmons, 2007; Lambert, Clark, Durtschi, Fincham, & Graham, 2010). In the context of a survey, recipients of a prepaid incentive might later complete the survey not because of indebtedness

(repayment of a debt) but because of their intention to maintain the positive “relationship” with the survey researchers who gave a prepaid, unconditional gift. Previous research found that people are more likely

4

to engage in prosocial behaviors when they are thanked in advance (Grant & Gino, 2010; see also

Bartlett, Condon, Cruz, Baumann, & DeSteno, 2012; Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006; Tsang, 2006). A prepaid, unconditional payment might evoke a sense of gratitude toward the survey researchers, which in turn could increase survey participation because it is construed as a prosocial behavior.

More generally, an unconditional gift could generate positive feelings (e.g., feeling happy) toward the survey researchers, which could also encourage survey participation, if the choice to participate is construed as prosocial. Psychologists have repeatedly found that positive moods increase prosocial behaviors. For instance, on a pleasant day (when people are in generally happy moods), pedestrians were more likely to cooperate with an interviewer and complete a survey than on an unpleasant day

(Cunningham, 1979). In a similar vein, Singer and Ye note that prepaid incentives might put respondents in an optimistic mood (2013, p. 130).

Likewise, a large body of research has shown that trust and moral obligation increase cooperation (see

Ballet & Van Lange, 2013 for review of trust; see Brummel & Parker, 2015 for moral obligation). Thus, an unconditional gift could evoke a sense of good citizenship because the prepaid payment demonstrates that the survey researchers had good faith and trust in recipients to begin with, which might in turn make the recipients feel obliged to and even want to reciprocate the good feeling by completing the survey.

It is quite possible, then, for people to feel a sense of obligation independently of any specific indebtedness. When asked directly why they would respond to a survey, many people give altruistic reasons

(Porst & von Briel 1997, Singer & Ye 2013). People who are strong in community attachment are more likely to respond to an RDD telephone survey (Guterbock & Hubbard 2006, Guterbock & Eggleston

2013). These more diffuse types of obligation (community attachment or “civic duty”) may trigger survey participation in the absence of monetary incentives (Groves, Singer & Corning 2000). On the other hand, in line with the research cited above, persons with strong social attachments and greater social capital may also be predisposed to respond to the prepaid incentive with greater trust and have other positive perceptions of the survey request.

Group differences. Not unrelated to these psychological constructs are the widely observed cultural and racial/ethnic differences in response rates to surveys (as well as participation in research studies of all types). The realized, unweighted set of completed interviews in most general population surveys nearly always over-represent women and under-represent African-Americans and Hispanics. In contrast, Asians are often well represented or even over-represented. Differences in social trust between blacks and whites are well documented (Kohut 1997, Guterbock, Diop & Holian 2007), and we might then expect that prepaid incentives would operate differently on these culturally distinct groups. Likewise, Asians report feeling indebtedness to a benefactor to a larger extent than do others (Oishi et al., 2015). The idea that various features of the survey request operate differently on different people is partially captured in

“leverage-salience” theory (Groves, Singer & Corning 2000). Salience refers to the prominence the requestor gives to each feature, while leverage refers to how much effect each feature will have on a particular sample member’s participation decision. With respect to incentives, this body of theory suggests that offers of money might have more appeal (leverage) for people who do not have much money. This is quite plausible and has some empirical support (Singer & Ye 2013), but the idea is expressed in a framework of cost-benefit analysis (Singer 2011) that —with its roots in rational choice theory (Schnell 1997)--tends to minimize the holistic nature of the survey participation decision and overlooks the possibilities, discussed above, that prepaid incentives affect the way sample members perceive other key features of the survey request and that these effects might in turn be moderated by cultural and community factors.

Research questions

1) Why does a prepaid incentive produce better survey responses? What are the psychological mechanisms? 1a) Does a survey request accompanied by (a) a token prepaid monetary incentive (b) a contingent monetary incentive (c) both a prepaid incentive and a contingent incentive [ “double incentive”] or (d) no incentive make people feel more (or less) indebtedness, gratitude, obligation, happiness, trust or

5

have other psychological reactions? 1b)

Which of the perceptions and psychological reactions are predictive of survey participation? 2) Is the effect of each incentive condition moderated by cultural and community factors? 2a) Is the effect of each incentive on survey perceptions and psychological reactions moderated by culture and community factors? 2b) Is the effect of each incentive on survey participation moderated by culture and community factors?

In our proposed studies, we will test these various psychological mechanisms simultaneously. Previous psychology research tended to study a few emotions at a time (e.g., gratitude’s effect on prosocial behavior, in contrast to amusement, Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006). Thus, it was unclear whether the effect was unique to one target emotion (e.g., gratitude) as opposed to other related emotions (e.g., happiness, indebtedness) or other related psychology (e.g., legitimacy). In addition, relatively few studies on emotion assessed actual social behaviors as key outcome measures (see Bartlett et al., 2012; Bartlett & DeSteno,

2006 for exceptions). Indeed, Baumeister, Vohs, and Funder (2007) criticized recent psychology research as “the science of self-reports and finger movements: Whatever happened to actual behaviors?” Our lab experiments will allow us to examine whether particular emotions or psychological states will predict a practically important, actual social behavior, namely survey response, above and beyond other related emotions and psychological states. To this end, our proposed studies will build on and contribute to psychological research on emotion and interpersonal behaviors in general, and research on gratitude, indebtedness, and trust in particular.

Pilot studies

Field experiment on incentives (Fall 2014): Design and hypotheses

During the Fall of 2014 Center for Survey Research (CSR) conducted a field experiment on the effects of prepaid (non-contingent) cash incentives, funded by a Seed Grant from the UVa Quantitative Collaborative, an interdisciplinary center that aims to foster quantitative social science research.

Sample. We used address-based sampling to select households in the Charlottesville area. At our direction, the sampling provider generated three separate samples. One sample was targeted to households with an Asian resident, one was targeted to African-American households, and the third was a general sample of all households.

Design and treatment groups. We used postal mail to request that sample members complete a survey on the Web. No paper version was provided. The experiment used a 2 x 3 design: incentive vs. no incentive, crossed with three ethnically based sample groups. We mailed to 375 households in each treatment group (1,125 receiving $2, and 1,125 with no cash incentive), for a total of 2,250 sampled households. After 10 days, all households received an identical reminder postcard.

Questionnaire. Questionnaires were virtually identical across treatment groups. The instrument, launched via the Qualtrics survey tool, was loosely based on an omnibus questionnaire used by CSR in Spring

2014. The questionnaire also included the following newly written questions aimed at measuring the respondent’s perceptions of the survey and the survey experience (“survey perception items”):

● Confidence: “How confident are you that the answers and personal information you give in this survey will be kept confidential and secure?” (6-point scale, “highly confident” to “highly doubtful”).

6

● Legit1: “How confident are you that important social scientific knowledge will result from this study?” (same 6-point scale).

● Legit2: “How confident are you that this study will produce new information that might be of interest to the general public?” (same 6-point scale).

● TimeUse: “How do you feel about the time you spent completing this survey?” (4-point scale,

“very good use of my time” to “complete waste of my time.”)

● Difficulty: “How easy or difficult was it to complete this survey?” (4-point scale, “very easy” to

“very difficult”).

● Valuable: “How valuable do you think your individual response will be for the researchers?” (4point scale, “very valuable” to “not at all valuable”).

● Appreciate “To what extent do you feel that your participation in the survey will be appreciated by the researchers?” (4-point scale, “very appreciated” to “not at all appreciated”).

● Obligated: “When you received the survey request in the mail, did you feel…” (4-point scale,

“highly obligated” to “not at all obligated”).

● Guilty: “How would you have felt if you had decided not to take the survey?” (4-point scale, “very guilty” to “not at all guilty”).

● YPartic1: “What made you decide to participate in this survey?” (open-ended text item).

● YPartic2a [asked only of those who received $2]: “How was your decision to participate in this survey influenced by the $2 you received in your invitation letter?” (5-point scale, “very positively” to “very negatively”).

Hypotheses: We expected that there would be a higher rate of response from sample members in the incentive condition than in the no-incentive condition, as found repeatedly in many prior studies. Based on the idea that a person’s sense of indebtedness is in part culturally determined, and Oishi et al.’s (2015) prior work showing a higher sense of indebtedness among Asians in experimental situations, we hypothesized that the effect of the incentive on response rates would differ across the three samples, with the incentive having the greatest effect on response rate among Asians. For the African-American sample, we thought we might also see a higher effect of the cash incentive if members of that group were lower in income, making the cash gift more important to them (or, as stated in leverage-salience theory, giving the cash more leverage to these sample members).

We also expected that the incentive treatment would have measurable effects on the respondent’s perception of the survey, with those in the incentive condition showing higher trust in the sponsor and in the confidentiality of the survey, seeing greater benefits from completing the survey and lower costs in completing it, and displaying higher levels of obligation than those in the non-incentive group. We also expected to see differences across the sample groups in some of these sentiments, with Asians showing higher levels of obligation than others.

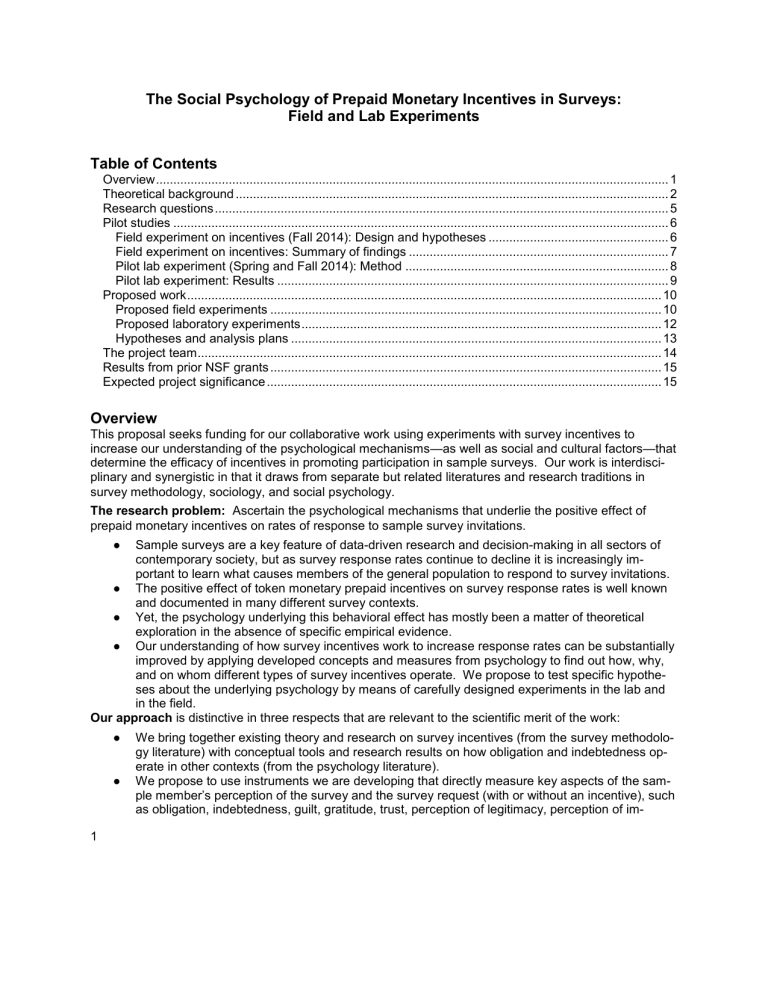

Field experiment on incentives: Summary of findings

● The $2 cash incentive, as expected, had a strong effect on response rates (15.9% for the prepaid incentive, 6.7% for no incentive).

● The measures of survey perceptions showed many substantial differences between prepaid incentive and no-incentive respondents (see table below). o Advance incentive respondents had a significantly higher level of obligation and substantially greater sense of hypothetical guilt (had they not completed the survey). o The prepaid incentive had substantial effects on other perceptions of the survey, including the sense of it being a worthwhile use of time, that results would be important, and that a response would be valued and appreciated. o These results substantiate our argument, following Dillman, that the prepaid incentive positively affects a range of perceptions that are key to the Tailored Design Method: legitimacy, trust, and perceived costs of the survey task.

7

o Overall, the results suggest that our measures of the survey perceptions have construct validity as well as face validity.

● A factor analysis of the perception variables indicates that obligation and guilt are closely related, while the o ther indicators (except “difficulty”) cohere in a separate perception factor.

● Asian respondents had higher levels of felt obligation, greater potential sense of guilt, and were more likely to say that the $2 incentive positively affected their decision to participate. o Nevertheless, the response rate ratio (cash/no-cash) for the Asian-targeted sample was no greater than for whites; this is partly attributable to the high level of obligation felt by

Asians in the no-incentive treatment.

● African-Americans had lower rates of response than other races in both the prepaid and noincentive groups. o But financial need was not correlated with incentive treatment.

● 73% of Asians in the prepaid incentive treatment said the incentive influenced their decision to participate either somewhat or very positively, compared to 17.6% of whites and just 11.1% of blacks in the prepaid incentive treatment.

Comparison of prepaid incentive and no-incentive treatment on survey perception variables

VARIABLE Content

T-test for difference of means:

Relationship

Effect size

P-value

N of cases

Legit1

Legit2

Timeuse

Valuable

Appreciate

Guilty

Confident social science knowledge will result

Confident info for the public will result

Good use of your time?

Your response valuable?

Your participation appreciated?

How guilty if you had not done survey?

Prepaid incentive treatment [$$] more confident

$$ slightly more confident

$$ better use of time

$$ more valuable

$$ slightly more appreciated

$$ more guilty

0.34

0.18

0.40

0.26

0.17

0.26

0.019

0.204

0.006

0.082

0.257

0.073

228

228

228

224

224

227

Chi-square from simple cross-tabulation:

Obligated

Did you feel obligated to take survey?

Difficulty

Confidence

Easy or difficult?

Confident results will be kept confidential

$$ clearly more obligated

$$ a little easier

No clear direction

0.20

0.13

0.19

0.026

0.297

0.124

227

228

228

Pilot lab experiment (Spring and Fall 2014): Method

Participants. Participants for the laboratory study (funded by the same UVa Seed Grant) were recruited through the University of Virginia psychology participant pool in exchange for partial course credit. A total of 215 participants were invited to take the survey. Of the 215 invited participants, a total of 87 (40.5%) eventually completed the online survey.

Materials. All participants who were invited to take the online survey received a letter describing the invitation. Depending on the participant's assigned condition, the letter either contained $2 in cash

8

(prepaid condition) or else notified participants that they would receive $2 if they completed the online survey (contingent condition). All participants also completed a brief mood scale immediately after receiving the invitation to complete the survey. The paper questionnaire asked about 11 emotional states: happiness, satisfaction, pride, gratitude, obligation, appreciation, sadness, anger, indebtedness, shame, and guilt. Participants reported the degree to which they were currently experiencing each emotion on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely). Finally, participants who chose to complete the online survey answered a variety of questions about community attachment, trust, their response to the survey invitation, and demographic information.

Procedure. In order to measure immediate emotional responses to the survey invitation while allowing survey participation to remain voluntary, we chose to add the survey invitation to the end of several ongoing, unrelated lab studies within the department. Our research assistants coordinated with the experimenters for the lab study so that they could arrive shortly before participants completed the lab tasks. The lab study experimenter would then introduce our research assistant, indicating that he or she had asked for a chance to notify the participants about an unrelated research opportunity. Our research assistant (who was pretending to be a research assistant of the Center for Survey Research) then explained the survey and gave participants an invitation letter, notifying them about the $2 in the envelope

(prepaid incentive) or informing them that they could receive $2 upon completion of the survey (contingent incentive). (The pilot experiment did not include a no-incentive treatment.) Next, our research assistant thanked participants and left the room. The lab study experimenter (the experimenter of the ongoing, irrelevant study) then returned to the room and told the participants that he or she *forgot* to give them one more form to complete for the original study. This additional form was our mood scale, which we wanted participants to believe was part of the lab experiment and not related to the survey announcement (to reduce experimenter demand effects). About a week after the lab portion of the study, participants received an email invitation from CSR to complete the online survey. If participants chose to take the survey, they clicked a unique link in the email (which allowed us to identify which participants took the survey) that opened a 15-minute Qualtrics survey. Those in the contingent condition who completed the survey were then mailed $2 to an address of their choosing.

Pilot lab experiment: Results

Predictors of response rate. As predicted, participants randomly assigned to the prepaid incentive condition were significantly more likely to complete the survey (51.5% completed) than those in the contingent incentive condition (35.1% completed), p = .015. Additionally, female participants were more likely to complete the survey (51.5% completed) than were male participants (30.7% completed, p =

.004).

Mood scale. As predicted, participants in the prepaid incentive condition reported feeling marginally more indebtedness (M = 2.07) compared to those in the contingent condition (M = 1.74, p = .083, the effect size

Cohen’s d = .260). With regard to other mood items, however, participants did not differ by incentive condition. So, although the difference found for indebtedness is modest in magnitude, it reflects a unique difference between the prepaid incentive and the contingent incentive conditions.

Mood as predictor of survey response.

Contrary to expectations, self-reported indebtedness immediately following the survey invitation did not predict survey response. A logistic regression analysis showed a non-significant, inverse association between the intensity of indebtedness and likelihood of completion.

Thus, the effect of prepaid versus contingent incentive on survey completion was not explained by the feeling of indebtedness. Indeed, the logistic regression analysis showed a significant effect of the manipulation above and beyond the feeling of indebtedness.

Also unexpectedly, three out of the 10 other moods measured (happiness, anger, and sadness) were associated with survey completion. Specifically, happiness was marginally positively associated with survey completion. In contrast, anger was significantly negatively associated with survey completion.

Similarly, sadness was marginally negatively associated with survey completion.

9

Perceptions of the survey invitation. The online survey asked several items about perceptions of the survey invitation, including whether the respondent felt obligated when receiving the invitation to complete the survey, whether they would have felt guilty if they hadn’t completed the survey, and whether they thought that the researchers would appreciate their response. Comparing these items across condition, participants in the prepaid incentive condition who actually responded to the survey reported (retrospectively) feeling more obligated to complete the survey compared to those in the contingent condition (p =

.002). Similarly, those in the prepaid condition reported that they would (hypothetically) have felt guilty if they hadn’t completed the survey to a greater extent than those in the contingent condition. There were no differences between the two conditions in terms of how valuable they thought their responses would be to the researchers or how much their participation would be appreciated.

However, contrary to expectations, the sense of indebtedness did not predict online survey completion.

This finding lends credence to the idea that prepaid incentives can affect variables other than indebtedness to spur a favorable response to the survey invitation. Interestingly, participants who were feeling less angry, less sad, and happier at the time of the study announcement were (marginally) more likely to complete the survey than others. Considering the link between these moods and positive citizenship behavior (e.g., George, 1991), these findings suggest that another way to improve survey compliance might be to evoke happy moods and reduce sadness and anger. This finding would be consistent with the idea that people who strongly identify with being a model citizen complete surveys not because of incentives but in order to fulfill their duties as citizens (cf. Guterbock & Eggleston on community attachment, 2013). On the other hand, participants for this study were recruited from various ongoing laboratory studies in the psychology department. This fact makes it unclear whether observed mood differences were the result of the content of the experiment that occurred before the survey invitation, the survey invitation itself, or pre-existing mood differences.

Another main limitation of the pilot experiment was that we did not have a no-incentive condition. Finally, we did not measure trust and other psychological mechanisms at the time of the survey announcement.

We will address these issues in the proposed new studies.

Proposed work

The current proposal seeks funding for field experiments and lab experiments that will be generally patterned after the approaches used in our pilot studies but will test more incentive conditions across a larger number of cases, with several refinements to the methodologies that grow out of our experience with the pilot experiments.

Proposed field experiments

We propose an incentive experiment in a multi-mode household survey to be conducted in the National

Capital Region [NCR], which is defined as Washington, DC and ten surrounding cities and counties in

Virginia and Maryland. Households will be sampled using address-based sampling, including households with and without available telephone numbers. The survey incentives will be varied randomly across five experimental conditions: no incentive, $2 cash prepaid incentive, $2 cash contingent incentive, $10 gift card contingent incentive, double incentive ($2 prepaid + $10 gift card contingent). Other than the description of the incentive, the survey appeal will be constant across all treatments, and will emphasize the goals of helping identify problems in the community and finding solutions for these problems.

We choose to survey the NCR because of the population diversity it offers us. With simple random sampling, we expect to achieve usable counts of AfricanAmericans, who are 25% of the area’s residents.

To achieve a sufficient number of completions by Asians, we will add a supplementary sample of Asians listed in the Experian proprietary database. Since households appearing on that list probably have different propensities to respond, we will also add —for comparison—a supplement of non-Asian households from the same source. From the prior work of Guterbock and Eggleston, we have surveybased measurements of the degree of community attachment in each ZIP code in the region. This information will allow us to enrich our sampling frame so that we will have local community attachment

10

estimates in addition to standard demographics of each sample member’s census block group (from

American Community Survey data and the just-released Census planning data base).

The questionnaire will be nearly identical for all treatments, differing only in a question or two that asks directly about the incentive. The questionnaire will be pretested in a focus group with area adults to be recruited by phone. The main body of questions will ask about metropolitan and community issues, and —following Dillman, Smyth & Christian (2014)—pictures on the booklet cover will help to reinforce the theme as being the local area. Direct measures of community attachment will also be included in the questionnaire. The closing section of the questionnaire will include questions developed in our pilot work to evaluate perceptions of the survey request and the survey task (see list above). We will add questions asking how closely they read through the mailed materials Most of these items are answered with ordinal scales. We will also examine measures of data quality and respondent effort to see if these are enhanced based on incentive or survey perception variables (Medway & Tourangeau 2015).

A “Web-push” Web-plus-mail approach will be used because it combines advantages of Web and mail modes, offers cost advantages over mail only, and allows direct delivery to sample members of token, prepaid cash incentives. Messer & Dillman (2011) used this approach and found that a prepaid incentive was especially effective in increasing the initial response via the Web. In the proposed experiment, sample members will initially be asked to respond on the Web, and alternatively by returning a paper questionnaire sent later in the process. (For our pilot we collected data only on the Web). We propose to conduct the survey in English only because supplying non-English versions requires further respondent contacts, which could obscure the incentive effects. We will send to each sampled household an advance letter, followed by an invitation letter with a Web link (which will include the prepaid incentive for two of the treatment groups). After a postcard thank-you/reminder (with Web URL) to all sample members, non-responding households will be sent a paper proposal packet with a letter (including URL), a paper questionnaire and a business reply mail return envelope. A final postcard will be sent to remaining non-respondents shortly before the field period ends. Respondents in the contingent-incentive treatments will receive a thank-you letter with their reward enclosed, sent upon receipt of their completed questionnaire. The sampling plan appears below; response rates are projected from M esser & Dillman’s results with similar protocols (2011). The proposed sample sizes will provide sufficient power to test the fairly modest effect sizes shown in our pilot survey for the perception variables. For example, comparison of the respondents in the ABS sample treatment groups for no incentive and $2 prepaid incentive would have over 80% power to detect an effect size as small as .22.

Treatment Expected

Response

Rate

Desired n of

ABS sample completes

ABS sample n needed no incentive

$2 prepaid

$2 contingent

$10 contingent

$2 prepaid +

$10 contingent total

25%

40%

27%

28%

43%

350

350

250

200

250

1400

1400

875

926

714

581

4496

Desired n of

Experian sample completes

200

200

150

100

150

800

Experian sample needed (50%

Asian)

800

500

556

357

349

2562

By including a dual-incentive treatment, we follow the example of Avdeyeva and Matland (2013). They used ruble-denominated incentives that are roughly worth $2 and $10, but the latter represented a value of half a day’s wages in the local economy. Perhaps for that reason, they did find a significant increase in response rate when the $10 incentive was offered conditionally —a rare finding in this literature. Their best-performing treatment was the dual incentive, combining prepaid and conditional incentives. In their

11

general population sample, each incentive had an effect when offered alone, and these effects were additive when both were offered. However, in their previous-participant sample, the double incentive performed no better than the prepaid incentive alone. In our study population, we expect to find that even a $10 conditional incentive will have little effect on the rate of response. However, it is possible that its effect might be enhanced if it is preceded by a prepaid incentive. If the prepaid incentive has the various effects on perception that we expect, then it could also change the sample member’s perception of the promise of $10 —for example, making it seem more certain or more ‘fair’ in relation to the requested task.

All the treatment groups with contingent incentives will be asked appropriate questions about how they perceive the fairness and the reliability of that offer, allowing us to test these hypotheses.

Proposed laboratory experiments

Although field experiments have many advantages (in particular external validity), they do not provide direct information regarding why some participants responded and others did not respond to the survey request. The unique advantage of the lab experiment is that it allows us to gather information from

(eventual) non-respondents, as well as (eventual) respondents at the time of survey request. Specifically, we will be able to assess how grateful, indebted, happy, trusted, respected and so forth they felt right after the survey request, and test whether these feelings and perceptions predict survey completion.

We propose two rounds of lab experiments, patterned closely after the design of our pilot experiments, but expanding the range of treatments, the planned measurements, and the number of cases.

Experiment 1

The experimental procedure will follow the protocol developed in our pilot study, with several refinements.

Specifically, participants will be University of Virginia students enrolled in introductory level psychology courses who have been recruited to participate in lab studies irrelevant to the present project. Toward the end of that study, a research assistant will visit the lab and make a survey announcement (again the survey is supposed to be conducted by CSR). The survey announcement will vary for the four treatments: no incentive, $2 prepaid incentive, $2 contingent incentive, and $2 prepaid + $10 contingent. The participants will be randomly assigned to one of the four incentive conditions. After the announcement, the experimenter for the “irrelevant” study will administer the last questionnaire, which measures moods and psychological states of participants at that time. One week later, the research assistant from CSR will send a web survey link via e-mail. Thus, we will have information regarding who completed the survey.

This will serve as a main dependent variable.

Lab Study Materials and Procedure. The current mood scale (“how do you feel RIGHT NOW? I feel…” on the 5-point scale; 1 = not at all to 5 = very much) consists of the 11 items used in the pilot study (happy, satisfied, proud, grateful, obligated, appreciated, sad, angry, indebted, ashamed, and guilty) plus the new items that aim to capture social exchange experiences: “trusted,” “respected,” “cared for,” and “understood .” Unlike the procedure in the pilot study, we will also ask participants to complete a brief scale that measures moral obligation (“I have a duty to help others when I can,” “I feel obligated to contribute to the community” “It is my duty to make the world a better place,” the Obligation subscale of the Obligation and

Entitlement Scale by Brummel & Parker, 2015). These scales will allow us to measure key psychological states such as indebtedness, gratitude, obligation, happiness, as well as interpersonal perceptions such as feeling “trusted” and “respected” and feeling a more general moral obligation to engage in prosocial behaviors.

Another change from the pilot experiment is to administer the mood scale on two occasions, not just directly after the survey announcement but also once about a third of the way through the lab session

(i.e., well before the survey announcement occurs). This will allow us to assess changes in mood directly and thus discern the emotional reaction to the survey invitation more directly. This step will also allow us to assess base-line mood levels that may in part be attributable to the nature of the activity in the lab. We will embed the first mood scale in other scales in the “irrelevant” study, so as to minimize participants’ awareness of our research purpose.

12

In addition, the “irrelevant” study includes the questionnaire that assesses participants’ dispositional factors such as Big Five personality traits (the 44-item Big Five Inventory, John, & Srivastava, 1999), sense of belonging to the UVa community (Motyl, Iyer, Oishi, Trawalter, & Nosek, 2014), and demographic factors such as socio-economic status (e.g., household income), race, and hometown. As in the proposed field study, these items will allow us to test the second set of hypotheses regarding whether the effect of a particular incentive would be stronger among certain participants (e.g., conscientious people) than others.

The Web Survey.

While the field experiment will use community as a survey theme and explore possible effects of community attachment on the expected incentive effects, “local community” has ambiguous meanings for college students, most of whom are not native residents of Charlottesville. Therefore, the questionnaire offered to the students wil l deal with current campus issues, and we will measure students’ subjective sense of “belonging” and “loyalty” to the University as a surrogate for community attachment.

The Follow-up Survey for Non-Respondents . Because our participants in the lab experiment come from the psychology department’s participant pool, we will be able to identify those who did not complete the web survey, and request them to participate in another survey for additional credits toward their research participation requirements. The follow-up survey will be brief, including the items on perception of the initial survey and the survey request, but also including open-ended questions regarding why they did not complete the web survey requested by CSR. This way we will be able to obtain additional qualitative, as well as quantitative data from non-respondents.

Power Analysis. We will have the capacity, over the course of the academic year 2016-17, to test four treatments with 80 subjects in each treatment (total n = 320). Church’s (1993) meta-analysis of 43 prepaid incentive studies found that the prepaid incentive had a mean effect size of d = .35 over the noincentive condition. The true effect size of prepaid incentive was likely underestimated by the metaanalysis, because it includes some studies with very small incentives. Indeed, Avdeyeva and Matland’s

(2013) recent study (with the university letterhead and one-shot contact conditions, which is the most similar to our proposed study) had far larger effect sizes, ranging from d = 1.21 for the double incentive condition to an effect size of d = .62 for the contingent incentive condition. Thus, we can expect the effect sizes for response rates to range from medium (d = .50) to large (d = 1.00). A power analysis with the two-tailed alpha set to .05 and a conservative effect size of d = .50 shows that 80 participants in each condition will have 88% power to detect differences between conditions (and 99.5% power if we used the expected effect size of d = .75). We will be measuring mood variables before and after the survey request, affording us 80% power (in a 2-tailed paired T-test) to detect changes with effect sizes as small as d = .33 within a single treatment group (n = 80) or d = .22 if we can combine two treatments (n = 160).

We propose to test the no-incentive, $2 prepaid, $2 conditional, and the double-incentive ($2 prepaid +

$10 conditional) treatments in the first experimental round.

Experiment 2 (A Follow-up Experiment)

For Fall of 2017, we have capacity to test three treatments, by the same general protocol, with 80 participants in each. We leave the treatments unspecified for the second round, as we expect the second round to include refinements in instrumentation, protocol, and incentive treatment that will derive from what we learn in the first round of the lab experiment and the field experiment. For instance, if the effect size of the $2 contingent condition was negligible in the first experiment, then we will remove this condition and include only the no-incentive condition (control), $2 prepaid incentive, and $2 prepaid + $10 contingent. If, for example, we find that “respect” was a strong mediator in Experiment 1, then we will measure respect more thoroughly, using multiple-item measures, in Experiment 2.

Hypotheses and analysis plans

Although the field experiments and the lab experiments will be analyzed separately, our hypotheses and analytic approaches to the two data sets can be described concurrently. There is no need for post-

13

stratification weighting of our survey data, so variance estimation will be straightforward. We will be testing four types of hypotheses:

1) We expect the response rates to differ by incentive type, as has been found in previous studies. We expect the advance incentives to substantially increase AAPOR RR3 response rates, while contingent incentives will have much smaller effects or no effects. These differences will be tested using all sample members in each data set, with simple T-tests and also with logistic regressions in which response/no response is regressed on the incentive treatment and background variables. For the field experiments, background variables will be appended census block group and ZIP code characteristics, including community attachment . For the lab experiments, we will control for participants’ gender, SES, race, hometown size, sense of belonging at UVa, and Big Five personality traits. a. The same methods will be used in the field experiment to test racial differences in RR3, with the expectation of higher response rates for Asians and lower rates for African-Americans.

2) We expect that the incentive treatment will affect psychological states as measured in the mood instrument, which will be available only in the lab experiment results. That is, the prepaid incentive conditions will evoke more positive moods (happy, satisfied), more indebtedness, more gratitude, positive interpersonal experiences (e.g., “trusted,” “respected”), and more moral obligation. Again using data from all lab participants, we will compare time 2 mood (administered after the survey request has taken place) across treatment groups, using T-tests and OLS regressions with controls as described above. a. Since the mood scale will also have been administered earlier in the lab session, we will be able to assess how the incentives cause changes in mood. This can be tested by including y

1

as a predictor when background variables are regressed on y

2 , where y represents the score for an item on the mood scale.

3) Again drawing on the lab experiment data, we will test whether the effect of prepaid incentive on survey response is mediated by the mood/psychological variables. We will use Mplus 7.0, and run a multiple-mediator model with the error corrected bootstrap sampling of 10,000 (similar to the model used in Oishi, Kesebir, & Diener, 2011). This will allow us to identify mechanisms (e.g., “indebtedness” “trusted”) underlying the superior effect of the prepaid incentive on survey response. In addition, we will explore whether the effect of each incentive is different across race, SES, and personality traits by forming interaction terms between the experimental conditions and each of these moderators. The contrast coding used in our analyses will be based on Rosenthal, Rosnow, & Rubin (2000).

4) The items measuring respondent perceptions of the survey will be included in both the field and lab questionnaires, but in each case are measured only on survey respondents. In both the field results and the lab results, we will test for the expected differences across incentive treatments, expecting prepaid incentives to enhance each of the measured perceptions. a. In the field experiment, we will be able to test whether survey perceptions differ for Asians, African-

Americans and other respondents, controlling for self-reported demographics and appended background variables.

The project team

Thomas M. Guterbock is Professor of Sociology, Research Professor of Public Health Sciences, and founding Director of CSR at UVa. At CSR, he has completed over 400 funded survey projects and his primary research area is in survey methodology. Shigehiro Oishi is Professor of Psychology at UVa whose experimental work in social psychology has focused on the causes and consequences of wellbeing, with a focus on culture and social ecology. Their collaboration on our seed grant was suggested by Casey Eggleston when she was a social psychology doctoral student working as a research assistant in Oishi’s lab and a research analyst for CSR. Eggleston is now a full time methodologist at the U.S.

Bureau of the Census. Although she will not be compensated from this grant, she will continue to collaborate in research design and analysis of results, since her position includes support of 10% of her time for independent research. Jolene D. Smyth , a former student of Don Dillman and his co-author on several editions of the leading textbook in survey methods, is Associate Professor of Sociology at

14

University of Nebraska —Lincoln, where she specializes in survey methodology and gender. She will be a paid consultant on the grant and will collaborate with the team on research design and interpretation of results. Deborah Rexrode is currently Senior Project Coordinator (soon to be Director) at the UVa Center for Survey Research. She will have operational responsibility for the proposed field experiments and will collaborate on testing of the questionnaires, research design, and interpretation of results.

Results from prior NSF grants

In June of 2010, Guterbock was contacted by NSF about conducting a workshop, on quick turnaround, to evaluate and recommend improvements in the instrumentation of NSF’s biennial surveys of public knowledge of and attitudes toward Science. Results of those surveys are published in Science and

Engineering Indicators , and the 2010 report had run into serious criticism from the National Science

Board, resulting in omission of some survey results from the report and some unfavorable publicity. A grant for $50,000 was issued to the University of Virginia, with Guterbock as PI ( “Science Indicators

Instrumentation Improvement Workshop,” BCS-1059876, 9/2010-8/2011). Intellectual merit: A highly successful, interdisciplinary workshop involving 13 participants was convened at NSF headquarters on

November 12, 2010. Broader significance: The final report was submitted to NSF’s Science Resources and Statistics Division (Guterbock 2011). Results were presented at the NS B’s February 2011 meeting by Myron Gutmann, Associate Director for SBE, discussed in the pages of Science , and subsequently published (Toumey, et al. 2013). NSF used the results to improve its measures of science knowledge.

Guterbock (with Barry Edmonston, co-PI) received a grant from the Sociology Program of NSF about 35 years ago to pursue mathematical and statistical modeling of urban density gradients. Grant No. SES-

7926182, "Population Deconcentration in U.S. Metropolitan Areas," April 1980 - December 1981.

Supplementary grant, January - December 1982. Total award: $92,578. Several journal articles resulted from this grant, culminating in an article by Guterbock (1990) linking urban density to annual snowfall.

Expected project significance

What we expect to add to scientific knowledge: As many others have demonstrated in prior research, small, prepaid cash incentives are highly effective in increasing rates of response, while contingent ( quid pro quo) incentives have little if any positive effect on response. Our contribution will be in showing how, why, and for whom these effects occur. In particular, we expect to show that prepaid incentives do not merely create a sense of indebtedness and obligation in the recruited sample member, but also have a positive effect on the sample member’s perception of legitimacy, trust, burden, survey importance, and related perceptions that affect the participation decision. Conversely, we expect to show that contingent incentives are ineffective because they fail to produce these positive psychological responses. Identifying the precise social psychological mechanisms underlying incentive effects will help surveyors identify other features of survey implementation that could trigger these mechanisms, thus increasing response.

Additionally, our research will contribute to the social psychological literature on emotion by explicating the role of various emotions, trust, and legitimacy in an actual, important social behavior (i.e., survey response). We will also be able to measure and explain differences between demographic and cultural groups (Asians, African-Americans, others) in how incentives affect perceptions of the survey request.

Our findings in this area will contribute to survey methodology’s existing knowledge about adaptive design, allowing surveyors to use incentives more effectively to maximize response, minimize nonresponse error and lower survey costs via adaptations during the survey field period.

This research will have broader impacts in that our findings promise to be of practical significance to anyone attempting to conduct a scientific sample survey in this time of declining response rates (e.g., businesses; government agencies; academics; nonprofits; schools; etc.). It is increasingly clear that survey research is in a crisis regarding practical ways of obtaining sound general-population samples

(Guterbock & Tarnai 2010). As response rates have continued to decline, the use of incentives is becoming standard practice. With a better understanding of how incentives actually work to increase survey participation, they can be more effectively deployed, with the result that the quality of survey data could be improved and the cost of surveys better controlled.

15