Affirmative Responses to Capitalism Kritik

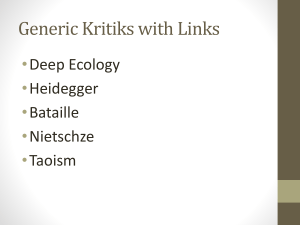

advertisement

OBSERVATION: Capitalism is not evil, Capitalism is both good and moral. Capitalism Is Not Evil, PhilosphyForum.com Sept. 9, 2010: Capitalism has proven to more efficiently and effectively utilize and allocate resources (both human and material) than other forms of economic systems. Countries which embrace market systems are wealthier and better off than those countries which have experimented with other economic systems (primarily socialism, communism or some form of central planning). Even the poorest of citizens in market systems are generally better off. Socialism or communism although attractive in theory ignore the realities of human nature (competitive and acquisitive) and stifle the innovation, industry and incentive which generate wealth and economic growth. DEAVEL: National Review, NationalReview.com June 22, 2012, Capitalism Is Good and Good for You, David P. Deavel, associate editor of Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture. The case for a free economy must be made, as Arthur Brooks has written in the National Review, on the basis of its moral foundations and not simply on its more efficient resource allocation. In Defending the Free Market, Fr. Sirico, president of the Acton Institute, has delivered an explanation of why “capitalism” — meaning private property, contracts enforced by law, and a price and interest-rate system established by the mutual consent of the parties involved — is not only the best way to meet human needs but also reflects and relies upon the moral and creative aspects of human beings. Is Capitalism Good? , TakeOnIt.com 2010: Capitalism is an economic system where wealth is controlled by individuals. It stands in contrast to socialism, where wealth is controlled by the government. Adam Smith (Father of Modern Economics), Jan 1, 1776: “Every system which [rewards an] industry a greater share of the capital of the society than what would naturally go to it, or [forces an] industry some share of the capital which would otherwise be employed in it, is in reality subversive of the great purpose which it means to promote. It retards, instead of accelerating, the progress of the society towards real wealth and greatness; and diminishes, instead of increasing, the real value of the annual produce of its land and labour.” Robin Hanson (Economics Professor) May 6, 2012: “This seems to me a common situation – things said to be critiques of capitalism are often just critiques of humanity. Humans vie selfishly and self-deludedly for status. Some succeed, while others fail. The struggles, and the failures, aren’t pretty. Yes capitalism inherits this ugliness, but then so does any other system with humans.” The Kritik Kritiks are philosophical arguments which question fundamental assumptions, or positions. The judge is asked to evaluate the round based on the kritik. Generally, the kritik is a tool for the Negative team. Kritiks have five characteristics: 1. The kritik questions fundamental assumptions. It looks at issues within the presentation, rather than taking the presentation at face value. The debate shifts from policy discussion, toward discussing questions of fact or value. 2. The kritik is presented as an absolute argument and demands a yes/no response from the judge. 3. The side presenting a kritik may use the same "hidden assumptions", however, decision on the kritik can mean a lost debate only for the opposing team. 4. The kritiks only questions and objects. It does not present an alternative. A kritik can suggest a realm of alternatives but not specify which one should be selected. A "kritik of capitalism," for instance, may urge that capitalism be rejected, and the Affirmative plan’s capitalistic underpinnings would be rejected as well. But the Negative presenting the argument would not have to urge for a specific replacement for capitalism. 5. Kritiks are "from the beginning" voting issues. They must be evaluated before substantive issues are considered. If the bedrock of the argument is faulty, then we can discard the argument without looking in detail. Kritiks are generic arguments. They do not look at the details that the other side has presented, but rather at the core reasons underlying the opposing case, or style and diction of the presentation. A kritik says that the way the opposing team has presented their arguments is having a bad effect on the process of debate or on the debaters and the judge in the round. These bad effects are so serious that the judge ought to give the offending side a loss. EXAMPLE: The Affirmative propose a plan that will be brought into effect by the federal government of the United States. The Negative team proposes a KRITIK OF STATISM. By proposing federal action, the 1NC says, the Affirmatives are implicitly saying that government is legitimate. But 1NC goes on to claim government should not be reflexively assumed to be legitimate. Governments are necessarily coercive: they force people to do things they don’t want to do, and this destroys human freedom. Governments become tools, therefore, for one class of people the rulers to oppress and control their fellow citizens, to silence their voices. And even worse, governments aren’t real. "Government" is merely a fiction, a word we use to describe a collection of people all believing and acting together; as far as natural rights go, individual persons have more rights than a make-believe concept such as "government" whose primary purpose is to deprive real people of their freedoms. Of course, the Negative speaker provides evidence for each of these crucial points. We come to the "impact" of the kritik: 1NC says that blind acceptance of government stifles our ability to conceive of other options. It numbs us to the alternatives. The impact is felt in the debate round, as the debaters become programmed by the language of "government" to be more accepting of government rights over peoples’ rights. What is the recourse? The only alternative to passive acceptance of "government", which has just been shown to be evil, is to reject the idea of government unless it can prove its worth. And the way to "reject government" is to reject the Affirmative approach, which is tainted throughout by the passive acceptance of government. So the judge is urged to vote against the Affirmative, not based on the merits or demerits of the plan, but because the way the Affirmatives presents their ideas requires a rejection. A kritik focuses on a hidden assumption made by the opposition. It argues that the assumption is a mistaken or an evil one. Finally, the kritik tries to have an impact on the round by arguing the mistaken assumption must be rejected, even though that means rejecting all the arguments of the opposing side. The Negative team’s only duty is to clash with the Affirmative at some point. Kritiks look to the assumptions embedded within the resolution, or within the Affirmative’s style of presentation. Negatives can argue that, if the resolution itself is based on a flawed assumption, then nothing flowing from the resolution need be debated, since it, too, will be flawed. Another argument on legitimacy: No matter what arguments are presented in the round, we’re just playing a game in debate. The judge does not really have the power to modify the status quo if she votes Affirmative. The only people really affected by what occurs in the debate round are the four debaters and the judge. Those who favor kritik arguments claim they have legitimacy to overlook the topic issues of the debate round in favor of examining the validity of the debate experience. A final argument on legitimacy: the premise that judges should listen with an open mind to any arguments debaters present, and evaluate them on their merits without regard to preconceptions. While this looks like a plea for debate evaluators to avoid judge intervention, the argument really has more radical implications: judges ought to be receptive to all theoretical positions which may arise in the round. Anything else imposes the judge’s opinions of "what debate ought to be" on the round, and forecloses some arguments either team might want to make; in turn, that may mean that before the round begins, some teams will be doomed to lose because the judge will not accept their argument. Debate theory is not written in stone, and that theoretical arguments should be evaluated as they arise. And that is why kritiks are legitimate arguments for debaters to explore. Although kritik may be a legitimate argument, that does not mean debaters are automatically going to win by running one. CAPITALISM The thesis is that capitalism is evil. It dehumanizes people, because it does not think of them as complex, individual persons but rather as "consumers" to be manipulated into making purchases or working for minimal rewards. The capitalist ethic reduces people to things, which fly in the face of centuries of moral philosophy. Promoting capitalism frustrates our efforts to look beyond the capitalist mentality, and thus must be rejected. Plans which operate within the capitalist system are corrupt and evil, and must be rejected so we can transcend the impulse to treat all things and all people as commodities. How does the opposing side respond to a kritik? The kritik is initiated by the Negative, in the 1NC. The burden of responding will be initially on the Second Affirmative speaker. A kritik should never be ignored. The Negative team will be trying the win the round based on the kritik’s decision rule, so you cannot afford to drop the argument. If you don’t understand what claims are made in the kritik, then you must use some time in cross-examination. Sometimes, that will reveal that the opposing team doesn’t understand their own kritik argument. There are four key approaches in responding to a kritik. Option 1: Reassert a comparative policy framework for the round: Kritiks often get a lot of their persuasive strength because the Negative is asserting that they do not have to meet the same standards that they set for the Affirmative. "The kritik doesn’t have to give an alternative to the plan," the Negatives say. "It’s enough that we show the plan isn’t as thoroughly conceptualized as the ideal Affirmative team would want it." That’s just absurd. Yes, the Negative might have a point if we were discussing philosophy in a classroom, but in a debate we’re locked into a competitive, comparative framework. A tactic will involve rebuilding the focus of the debate where it belongs: on the comparison of policy systems, rather than one-sided philosophical considerations. Potential Affirmative responses are as follows: •Social contract. We were invited to participate in policy debate at this tournament, so we need to restrict argumentation to traditional comparative policies. By accepting the invitation to debate, we have mutually committed to deal with comparative policy issues. •Policy debate is an inappropriate forum for kritiks. A debate is not an open forum; there is no rule which says we have to discuss everything which strikes any debater as an interesting idea. For an interscholastic debating format, kritiks represent too abstract an argument for our consideration. •"Permute" the kritik into an appropriate policy position. As we have observed already, most kritik resemble defective versions of conventional policy arguments. Respond to the kritiks as arguments in the conventional form, and point out their deficiencies. Option 2: Show the kritik is not compelling within the policy framework: Once the Affirmative shifts the debate back into a comparative policy-based mode, the next step is to show that the kritik fails to be persuasive if viewed as policy issues. The last tactic we looked at in the previous section, permuting the kritik, was already a step in this direction. Other arguments that the Affirmative team can make are: •The kritik is fundamentally incoherent. It does not make an argument, and therefore requires no response. Our opponents claim we’re doing something objectionable, but they can’t seem to express their objections in a meaningful way. They should not be allowed to reinterpret the kritik in later speeches: their initial presentation is so vague that they have forfeited the right to build on it. (This claim is especially appropriate against mumbled 1NC arguments that don’t seem to add up to any solid claim). •The Negative advancing the kritik is fundamentally inconsistent. At the minimum, we must insist that the Negatives advance no policy arguments which would themselves be subject to the kritik. It makes no sense to argue that causality does not exist and also that the plan would cause disadvantages, for instance; any Negative team trying to make both arguments in the same round should lose all credibility for either. •Within the policy framework of debate, kritiks fail to offer an alternative, and therefore they may be ignored. Policy debate is the weighing of contrasting policies: this gives no contrast, and so is irrelevant to the round. •This kritik does not apply to this Affirmative case. The Negative bases their kritik on exploring hidden assumptions of the Affirmative. We do not make the assumption that the kritik is trying to refute. •The kritik leaves holes to allow an Affirmative victory. The kritik asks us to rethink our beliefs and hidden assumptions. Fine, but that still permits us to reconsider our positions while the round is going on and decide that our initial position was right all along. "Rethinking" doesn’t always mean rejecting everything which has gone before: it really just means a pause for reflection. Fine, we’ve reflected, now let’s get on with life. •The non-absolute nature of the kritik allows for an Affirmative victory. Even if the kritik is almost certainly true, there’s enough residual uncertainty for Affirmatives to win in the absence of a competing policy argument. That’s because the kritik gives no real challenge against an Affirmative policy, just a challenge to the motives underlying the policy. Option 3: Refute the kritik on its own terms: •The kritik is untrue. Many kritiks are postulated on controversial philosophical grounds. Use evidence and reasoning to clash with the issue. •The fundamental assumption the kritik addresses is justified. Evidence and analysis, again. Option 4: Kritik the kritik: Turn the tables back on your Negative opponents. Their action in proposing a kritik implicitly endorses the legitimacy of kritiks. You can use that implicit argument right back at your opponents. The arguments you might choose to make: •The kritik itself has "hidden assumptions." Those assumptions are subject to kritiking. Many kritiks rely on post-structuralist, post-modern philosophical arguments which are very controversial. This would, of course, require evidence specific to the particular kritik at hand. •Kritiks lead to infinite regression. If all underlying assumptions need to be challenged, we can never reach a meeting of minds between teams, there’s always some other assumption in the way. The conventional debate round ends up in a decision one way or the other because there is always some common ground both teams can agree on, but the Negative has establishes the principle that every action of the Affirmative, the choice to speak in English, the choice to obey the rules of debate, is potentially abusive. •Kritiks are innately self-contradictory. The idea that "all assumptions must be questioned" is itself an assumption which must be answered before the kritik is allowed to go forward. In other words, the fundamental hurdle which must be passed is one Negatives set up in introducing the kritik in the first place: they must show that their kritik is not vulnerable to the perils of hidden assumptions. •Kritiks are nihilistic. If everything is subject to being questioned, then there are no grounds for believing anything. We are left staring into the void of paralyzing skepticism. That’s not a tolerable situation. We can reject the nihilism of kritiks on two grounds: (1) emotional grounds, it’s just too bleak to stare into the void; and (2) pragmatic grounds, paralysis stop us from getting on with life. Reject the idea of the kritik and step away from the void.