LSE Economic History Seminar Title: Waist not, want not: Measuring

advertisement

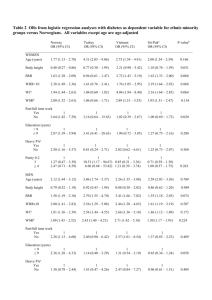

LSE Economic History Seminar Title: Waist not, want not: Measuring historical obesity using anthropometric data from two British tailors Extended Abstract: To date anthropometric historians have told a range of fascinating but often disheartening stories of deprivation, stunting, delayed catch-up growth and high mortality. This is a consequence of their overwhelming reliance on sources sampling the working classes, informing historians about socioeconomic conditions at the lower ends of society. My research tells no less of an alarming story in terms of historical health but focuses uniquely on life choices and over-indulgence rather than deprivation. Anthropometric history uses physical body measurements as a means of investigating historical standards of living. Anthropometric measures provide an alternative to gross domestic product (GDP) and real wage data as an indicator of standard of living for economic historians. They are useful for distant historical periods where traditional econometric data sources are nonexistent or unreliable, and for groups of the population unrepresented by labour data, including women, children, and elites with a passive income. Furthermore, bodies measure all inputs, capturing goods produced outside the market as well as within it. Each new development in anthropometric history has tried to contend with existing historical or methodological problems but encountered new limitations1. The challenge remains to uncover an anthropometric data source which: includes men and women, samples a broad age range, captures the household distribution of resources, contains measures of short-term nutritional status, enables cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis, and includes the upper classes. The solution I propose is the use of a new and original anthropometric source - tailors’ records. To exploit the copious potential of tailors’ records I have comparatively analysed data from two disparate bespoke tailors: 1. Morris & Son - tailors, drapers and dressmakers located in Barmouth, North-West Wales with measurement records for the 1890s. 2. Henry Poole & Co. Ltd. – ‘Savile Row’ tailors in Mayfair, London from whom measurements have been sampled from the second half of the nineteenth century. A brief context of these two tailors highlights the distinct nature of the demographic that they measured. During the eighteenth and early nineteenth century Barmouth was a busy harbour, exporting slate and stone from local quarries. In 1867 the Barmouth Viaduct was constructed, extending the railway to Barmouth. Local maritime industry suffered because the railway provided a cheaper means of transportation and the viaduct silted up the estuary so that it became navigable only by small vessels. However, the railway also brought tourists to Barmouth for the first time, transforming the port into a picturesque seaside For an outline of the development of the anthropometric field see, Steckel, R. H., ‘Heights and Human Welfare: Recent Developments and New Directions’, Explorations in Economic History, vol. 46, 1 (2009), pp. 1-23 1 resort. Barmouth experienced an economic transformation. With a population just over 2,000 in the 1890s2, there was lodging room for over 5,000 visitors in the small town by the turn of the twentieth century3. Amidst this economic transformation, with a monopoly over local tailoring requirements, Morris & Son acquired a clientele from a broad range of socioeconomic backgrounds, although especially the upper-middling classes. In contrast, the measurement books of Henry Poole & Co contain a sample of customers exclusively from the highest elites. In 1846 Henry Poole reoriented his livery shop and thus founded the tailoring industry on Savile Row in London, a road on to which the fashionable tailoring industry soon coalesced. Savile Row swiftly became the international peak of the bespoke tailoring craft, synonymous with exquisite style and impeccable quality. Henry Poole & Co. tailored for elites, aristocrats and royals. Consequently, anthropometric measurements within this second dataset represent individuals for whom there were few or no economic limitations throughout life. I have focused on analysing waist circumference and hip circumference because they highlight central adiposity and feature in wide ranging medical literature. The waist circumference of Morris & Son customers ranges between 20 and 48 inches; that of Henry Poole & Co between 27 and 57 inches. A comparison of the frequency distribution of waist circumferences of male customers to Morris & Son and Henry Poole & Co. reveals that there are individuals within both datasets with a high 2 Census of England and Wales. 1891. Ages, Condition as to Marriage, Occupations, BirthPlaces, and Infirmities, vol. III, 1893-94, CVI (1), p. 495 3 Hughes, J., Hughes’ New Guide to Barmouth, 2nd edn., (Barmouth: n.p., 1902), p. 8 adiposity, but as expected the elite customers of Henry Poole & Co. are more prone to larger waist circumferences. Using ‘action points’ points found in modern epidemiological studies it has been possible to analyse the proportion of individuals within the tailors’ records at threat of health issues associated with obesity. Based on current NHS guidelines, 15.6% of Morris & Son customers and 47.9% of Henry Poole & Co. customers were at increased danger of Type II diabetes with a waist circumference over 37 inches4. An alternative epidemiological study suggests that 5.8% of Morris & Son customers and 23.5% of Henry Poole & Co. customers with a waist circumference over 40.2 inches had 2.5 to 4.5 times greater likelihood of one or more major cardiovascular risk factors than those with a waist circumference less than 37 inches. An additional 9.8% of Morris & Son customers and 24.4% of Henry Poole & Co. customers with waist circumferences between 37 and 40.2 inches were 1.5 to twice as likely to have one of more major cardiovascular risk factors than those with a waist circumference less than 37 inches5. These analyses indicate that the greater degree of right skew to the distribution of Henry Poole & Co. waist circumferences places a much greater proportion of their customers at risk of health issues associated with large waist circumference and centralised adiposity compared to those of Morris & Son. A very large t value is generated by a comparison of means suggesting that it is highly unlikely that simply compositional effects are being observed. I Diabetes UK, ‘Measure Up – Are you at risk of diabetes?’, [http://www.diabetes.org.uk/Measure_Up_-_are_you_at_risk_of_diabetes/], 6 March 2012 5 Han, T.S., Van Leer, E. M., Seidell, J. C., and Lean, M. E. J., ‘Waist Circumference Action Levels in the Identification of Cardiovascular Risk Factors: Prevalence Study in a Random Sample’, British Medical Journal, 311, (1995), p. 1401. 4 find the wider dispersion of the Henry Poole & Co. waist circumferences unsurprising – whilst undernourishment is rarely chosen, obesity stems from life choices. Amongst the Savile Row clientele although a healthy range of waist circumferences remained typical, the higher incomes of the elites in this dataset, providing them with much greater purchasing power and choice over nutrients granted them the option to become fatter. There was a higher likelihood of a more sedentary lifestyle amongst those of a high social status in comparison to Morris & Son’s customers of whom over 70% of those with occupations noted worked in jobs with high energy requirements. Similar health analyses can be conducted using waist-hip ratio (WHR) as a gage of historical health. WHR is calculated by dividing waist circumference by hip circumference. The higher the WHR, the larger the waist circumference proportional to the hip circumference. Comparing the frequency distributions of WHRs within the two datasets, the WHR of Morris & Son customers ranges between 0.57 and 1.16; that of Henry Poole & Co. between 0.694 and 1.24. Both have a peak WHR around 0.9. The Henry Poole & Co. sample is more dispersed with a slightly larger range and a higher standard deviation that the Morris & Son data. The distribution from Henry Poole & Co. is very mildly skewed to the right whilst that of Morris & Son is almost perfectly normally distributed. Again, epidemiological action points suggest 7.8% of Morris & Son and 11.1% of Henry Poole & Co. male customers with a WHR greater than or equal to 0.98 had 2.3 times the risk of stroke compared to those with a WHR less than 0.896. A fairly low WHR, greater than 0.92 places males at threefold risk of prostate cancer compared to those with a WHR less than 0.867. This would place 41.9% of Morris & Son’s customers and 35.1% of Henry Poole & Co.’s customers at heightened risk. These analyses of the action points of various epidemiological studies suggest that more of Henry Poole & Co.’s customers are at risk when excess abdominal fat is measured using waist circumference and either a similar proportion or greater number of Morris & Son customers are at threat using WHR to measure central adiposity. The results highlight that amongst Henry Poole & Co. customers, although waist circumference can be particularly high, hip circumference is usually proportionally large and counteracts its influence on the calculation of WHR. I posit that in accordance with the ‘Barker hypothesis’8, Morris & Son’s customers were individuals not brought up in wealth; foetal and childhood deprivation may have impaired their development and demanded adaptation with long-term physiological impacts. Following an economic transition towards tourism, with the subsequent impact of higher incomes and more sedentary occupations, greater affluence gave Morris & Son’s customers larger waists without a skeletal frame (including hip size) or metabolic function to cope with this. Because Barmouth was in the early stages of economic transition in the late nineteenth century, affluence and over-nutrition was only just emerging and in general the waist circumferences of Morris & Son McCarthy, M., ‘Waist/Hip Ratio Predicts Stroke Risk’, The Lancet, vol. 348, 9043 (1996), pp. 1724-1724. 7 Hsing, A. W., Deng, J., Sesterhenn, I. A., Mostofi, F. K., Stanczyk, F. Z., Benichou, J., Xie, T., and Gao, Y-T, ‘Body Size and Prostate Cancer: A Population Based Case-Control Study in China’, Cancer, Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, vol. 9 (2000), pp. 1335-41. 8 Osmani, S. and Sen, A., ‘The Hidden Penalties of Gender Inequality: Fetal Origins of IllHealth’, Economics and Human Biology, 1 (2003), p. 117. 6 customers are not greater than those of the elites frequenting Henry Poole & Co. However, those Morris & Son customers with excess abdominal fat do not have a proportionally large hip circumference. And thus whilst there are fewer Morris & Son customers than Henry Poole and Co. customers with an unhealthy waist circumference, there are often as many, if not more, with a WHR placing them at health jeopardy. In contrast, those Henry Poole & Co. customers experiencing overnutrition with very large waist circumferences are likely to have been wellendowed from birth (and before that as a foetus), thus their hip circumferences are similarly large and proportionally fewer have a waist-hip ratio placing them at health risk. Although their waist circumferences are larger than the clientele of Morris & Son, all of them is larger and in terms of WHR this reduces their health risk. Furthermore, trends over time show that the waist circumference and WHR of Henry Poole & Co. customers was increasing in the second half of the nineteenth century – regressions reveal that time explains 37.3% of the movement in waist circumference and 24.5% of the trend in WHR. Longitudinal analyses confirm this. Focusing on the fifteen Henry Poole & Co. customers with five or more visits identifies that none of the customers sampled has a final waist circumference smaller than their initial one. Although there are instances of a fall in waist circumference, these are only experienced as short-term fluctuations amidst a general trend of increasing waist circumference. Increasing waist circumference is occurring throughout the period and at a similar rate for all longitudinal individuals. A similar upward trend in WHR is identifiable. Only one of the fifteen longitudinal customers has a final WHR lower than he started with. Many of the individuals seem to make the sharpest gains in WHR during the second half of the 1860s. Fluctuations in WHR appear to be felt for longer than those of waist circumference. In conclusion, tailors’ records are a valuable new anthropometric source. Cross-referencing tailors’ records with modern epidemiological results highlights that ‘diseases of affluence’ are not a modern phenomenon. Obesity posed a health risk for a significant portion of both my two nineteenth century populations. In particular, the elites visiting Savile Row had very large waist circumferences and worrying levels of central adiposity, although the rest of their body was proportionally large so that their health risks as measured by WHR were reduced. The economic transition experienced in Barmouth at the end of nineteenth century brought new wealth and affluence from tourism to a society not brought up as a foetus or child with abundant nutrition. With a weakened physical structure and metabolic function, Morris & Son’s customers gained larger waist circumferences without a physiology to support them. Although not fatter in terms of waist circumference than those on Savile Row, their disproportional WHR placed them at greater health risk. Trends over time show that the waist circumference and WHR of Henry Poole & Co. customers was increasing in the second half of the nineteenth century. Longitudinal analyses confirm this, identifying increased waist circumference and WHR over the course of individuals’ lives in this period.