View/Open - Sacramento

advertisement

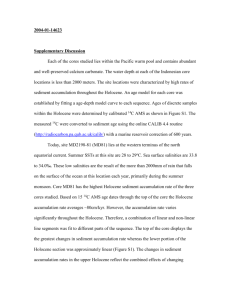

18 Chapter 3 PALEOENVIRONMENTAL, ARCHAEOLOGICAL, AND ETHNOGRAPHIC CONTEXT Paleoenvironmental Context Previous research indicates that cultural changes may be correlated with paleoenvironmental shifts in California (e.g., Arnold 1992; Jones et al. 1999; Kennett 2005; Moratto 1984; Moratto and Chartkoff 2007; Pierce 1988; Raab 1996; Schwitalla 2010). This concept is built upon foundations such as Baumhoff’s (1963, 1978) examination of California where he linked cultural adaptations to vegetation patterns. An understanding of paleoenvironmental trends may therefore help to explain the timing of and motivation underlying cultural patterns in prehistoric California. The study area is largely composed of aquatic environments, i.e., rivers, lakes, sloughs, marshes, comprising the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta (the Delta). Thus, cultural adaptations would likely be related to the stability and changes in these habitats. Paleoenvironmental data and reconstructions for the study area often rely on interpretations from adjacent regions. This is particularly true for the Early and Middle Holocene while data for the last 900 years of Delta development and Sacramento River flows is locally available (see Figure 3). The Pleistocene/Holocene Transition The end of the Pleistocene and advent of Holocene conditions occurred approximately 13,500 to 11,500 years ago. Climate was generally wet and cool, and the Sacramento Valley a large river basin with riparian forests and extensive grasslands. Freshwater marsh habitats were limited and megafauna abundant (Meyer and Rosenthal 2008:44). Fossil remains of grazers include Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi), ancient bison (Bison antiquus), camel (Camelops hesternus), Harlan’s ground sloth (Paramylodon harlani), western horse (Equus major), and their predators [e.g., dire wolf (Canis dirus) and saber-toothed cat (Smilodon floridanus)] support the dominance of grassland habitats (Meyer and Rosenthal 2008:42-43). As the Pleistocene/Holocene transition drew to a close, megafauna disappeared and humans began to occupy the landscape (Erlandson et al. 2007:62). These changes coincided with shifts in 19 temperature and precipitation that initiated the onset of modern Mediterranean environments across California. Early and Middle Holocene The Early Holocene dates from approximately 11,000 to 7000 years ago. The Middle Holocene dates from 7000 to about 4000 years ago. During the Early Holocene, global weather patterns grew warmer, precipitation decreased, and climate became more stable. Sea levels rose an average of 83 meters (272 feet) every 1000 years (Meyer and Rosenthal 2008:48). Sea level rise led to the formation of the San Francisco Bay estuary and its eastward expansion at a rate of approximately 30 meters a year (Atwater and Hedel 1976:8; Bickel 1976:11). Sea level rise slowed after 8000 B.P. and sediment began to accumulate, producing tidal marshes along the coast and inland Delta. By 6000 B.P., peat samples indicate vegetation patterns similar to those of today in the study area (Shlemon and Begg 1975). Climate during the Middle Holocene was typically warmer and drier, with a xeric peak occurring at 6800 B.P. (Minnich 2007:59). At roughly the same time there is evidence for a high-energy water flow in the San Francisco Bay and eastern Diablo Range that may have resulted from massive snow melt in the Sierra Nevada and Cascade ranges (Meyer and Rosenthal 2008:57). There is no evidence of Early Holocene human occupation in the study area and Middle Holocene sites are rare. When found, Middle Holocene sites are typically located on aeolian dunes and return radiocarbon dates commensurate with the latter part of the era (Meyer and Rosenthal 2008:52, 59). Late Holocene The Late Holocene dates between 4000 B.P. and the present. Close to 300 Late Holocene archaeological sites are present within the study area, typically located on high ground and river levees (Pierce 1988:16, 37). The Late Holocene marks a return to a cooler and wetter climate, with increased precipitation and less pronounced seasonal variations in temperature (West 2000 as cited in Meyer and Rosenthal 2008:64). This trend may have begun as early as 5000 B.P. and is associated with the increasing presence of moist westerly winds on the Pacific Coast; lower salinity in San Francisco Bay; new glacial formation in the Sierra Nevada; and the establishment of gray pine-blue oak woodland in the Sierra Nevada 20 foothills (Meyer and Rosenthal 2008:57; Minnich 2007:61). However, as the Late Holocene progressed, alternating periods of wet and dry conditions occurred (Adam 1975; Byrne et al. 2001; Gorman and Wells 2000; Ingram et al. 1996; Meko et al. 2001; Meyer and Rosenthal 2008; West et al. 2007). HOLOCENE Figure 3. Paleoenvironmental Chart. Figure 3 illustrates the correspondence between major climatic events, local paleoclimatic data, and archaeological temporal periods for the study area during the Late Holocene. As seen above, two climatic events are associated with the Late Holocene: the Medieval Climatic Anomaly (MCA) and the Little Ice Age (LIA). The MCA is defined as a time of increased aridity that resulted in droughts and warm temperatures in many parts of the world, particularly in western North America (Jones et al. 1999:138). The MCA lasted from 1150 to 600 B.P., although some researchers believe it may have began as early as 1500 B.P. (Ingram 21 1998; Kennett et al. 2007). Peat deposits from Rush Ranch in Suisun Marsh and tree ring data from the Sacramento River watershed suggest that drought conditions manifest by low freshwater flows and high salinity, occurred within the study area during the MCA. Data from Rush Ranch indicate reduced freshwater by 1750 cal. B.P., almost 600 years earlier than the start of the global MCA (Byrne et al. 2001:70, 75). These conditions persisted until about 750 cal. B.P., when freshwater flows increased. Instead, high salinity levels in peat deposits indicate that between 1750 and 750 cal. B.P. freshwater flows into Suisun Marsh were normally 44 percent lower than the lowest modern record in A.D. 1978 (Byrne et al. 2001:74). Similarly, tree ring data across northern California indicate low precipitation and stream flows in the Sacramento River watershed from 1095 B.P. to 960 B.P., with extremely low stream flows around 967 B.P. (Meko et al. 2001:1035). Tree ring data signal renewed drought conditions beginning in 630 B.P. through the beginning of the LIA at approximately 480 B.P. This suggests that during the MCA freshwater marsh habitats were likely smaller, riparian corridors dominated by slower stream courses and fewer sloughs, and grasslands probably more expansive and seasonally drier. The LIA (650 to 150 B.P.) was a global climatic event marked by lowered mean temperatures, glacial advances, expansion of polar pack-ice, and tree-line retreats (Koerper et al. 1985:99). In California, the LIA is associated with high lake stands in the Great Basin and the Matthes Glaciation in the Sierra Nevada (Meyer and Rosenthal 2008:65). Climate in the LIA was apparently colder, with temperatures one to two degrees Celsius (1.8 to 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) lower than today. Precipitation was likewise greater and, when combined with colder temperature, produced increased snow at higher elevations. At least five extreme floods are recorded in the study area during the LIA at 650 B.P., 600 B.P., 530 B.P., 390 B.P. and 230 B.P. (Gorman and Wells 2000:216; Meko et al. 2001:1035; West et al. 2007:24). Drought conditions are recorded in association with at least two of these flood events; at 658 to 649 B.P. and 372 to 370 B.P. (Meko et al. 2001:1037). This suggests that increased temperatures may have contributed to increased snow pack melt, though annual precipitation was insufficient to maintain normal stream flows. Droughts however, of briefer duration than those in the MCA, the longest estimated at just LIA 20 years between 658 and 649 B.P. (Byrne et al. 2001:74; Meko et al. 2001:1037). These climatic perturbations vegetation 22 habitats would have led to changes in vegetation, with expansive grasslands and slow-moving rivers, replaced by a mosaic of aquatic habitats with faster colder rivers, extensive freshwater marsh, and smaller seasonally flooded grasslands. Archaeological Context Extensive evidence for human occupation of the study area does not appear until the terminal Middle Holocene, circa 5000 to 4400 B.P.(Golla 2007:76; Meyer and Rosenthal 2008:63). Although Early to Middle Holocene occupation has been identified in surrounding vicinity, they are lacking in the study area (Meyer and Rosenthal 2008:60-62). This may be linked to the development of the Delta leading to changes in vegetation, inundation, deposition, erosion, and other taphonomic processes that destroy or cover sites. Once the Delta began to stabilize, evidence for human use of the area increases and regionally specific cultural traditions developed. A Brief History of Lower Sacramento Valley Archaeology Systematic archaeological investigations of the lower Sacramento Valley began in 1933, when J.B. Lillard and W.K. Purves of Sacramento Junior College excavated three sites near the confluence of Deer Creek and the Cosumnes River. On the basis of artifact seriation, stratagraphic principles, burial positions, and grave lots, Lillard and Purves developed the first archaeological chronology for the study area and Central California. Termed the Early, Intermediate, and Recent periods, the chronology developed by Lillard and Purves challenged Alfred Kroeber’s assertion that prehistoric California cultures had not changed over time (Moratto 1984:179). Additional excavations in the area led to an extended report and the formation of Delta Sequence. Temporal periods within the Delta Sequence were renamed the Early, Transitional and Late periods (Lillard et al. 1939). The Delta Sequence was later modified and expanded by R.K. Beardsley to include the San Francisco Bay region (Beardsley 1948, 1954a, 1954b). Renaming the temporal sequences identified by Lillard et. al (1939) as the Early, Middle, and Late horizons, Beardsley used this sequence as a framework for his development of the Central California Taxonomic System (CCTS). The CCTS concept was based on the Midwestern Taxonomic System developed by W.C. McKern for the American Midwest. In 1972, the tripartite scheme was again renamed, by S. Ragir after her 23 excavations at SJO-68. The scheme she proposed relied on the sites or regions cultural manifestations where each culture was first identified. Thus the Early Horizon became the Windmiller Culture; the Middle Horizon became the Cosumnes Culture; and the Late Horizon became the Hotchkiss Culture (Ragir 1972:189). With the advent of absolute dating, J.A. Bennyhoff, D.A. Fredrickson, and R.E. Hughes spent several decades attempting to refine the cultural chronology established by Beardsley (Bennyhoff and Fredrickson 1994; Bennyhoff and Hughes 1987). At the same time, investigations in the San Francisco Bay region increased and a local cultural chronology was established for the Bay Area (Moratto 1984:252). Ultimately, Bennyhoff and Hughes (1987) offered a general chronology for California and the Western Great Basin. By coupling Olivella shell bead types (largely from burial contexts) and radiocarbon assays, this chronology attempted to resolve California and Great Basin sequences while preserving of regional deviations. More recently, a synthesis of the Central Valley archaeological record by Rosenthal et al. (2007) has proposed a five part temporal scheme based on Fredrickson’s (1973, 1974) earlier proposed PaleoIndian, Archaic, and Emergent periods (Rosenthal et al. 2007:150). The goal of this synthesis was to correlate foothill, valley, and Delta sequences, incorporating settlement and subsistence patterns and new data from older sites, such as the Skyrocket and Los Vaqueros localities (Rosenthal and Meyer 2008:61 Table 6). Although the scheme works well for earlier periods, by 5000 B.P. regional variations are apparent, complicating its utility. Refinement of the Central Valley chronology remains a central issue of archaeological research, such that other aspects human behavior (e.g., subsistence patterns and technological features) are generally ignored. For the purposes of this analysis, the tripartite chronology of Early, Middle, and Late periods proposed by Bennyhoff and Hughes (1987) will be employed. Temporal frameworks are based on calibrated radiocarbon dates established by Groza (2002) using AMS dating of Olivella shell beads (see Hughes and Milliken 2007:265, Figure 17.2 Scheme D). The resulting chronology is as follows: Early Period will represent 4400 to 2450 B.P., Middle Period 2450 to 900 B.P., and Late Period 900 to 150 B.P. 24 Before the Early Period Although no Early (11,000 to 7000 B.P.) and few Middle Holocene (7000 to 4000 B.P.) sites are documented in the Lower Sacramento Valley, a brief discussion of these is warranted. Early Holocene sites in the greater northern Central Valley are sometimes referred to as Paleo-Indian sites and are associated with wide-stemmed dart points, flaked stone crescents, and a preponderance of milling equipment, such as millingslabs, handstones, and a variety of other cobble-based pounding, chopping, and scraping tools (Rosenthal and Meyer 2008:52). The distribution of Early Holocene sites indicates widespread use of foothill as well as the conifer zone of the Sierra Nevada and Coast Ranges. Based on these findings, settlement was likely semi-nomadic and subsistence focused on plant foods (including both small seeds and nut crops) supplemented by big game. A significant gap exists in the Middle Holocene record of northern Central Valley. Apart from a few insecurely dated sites (e.g., LAK-509/881), Middle Holocene material is confined to the eastern slopes of the Diablo Range and southern Sierra foothills (Rosenthal and Meyer 2008:59). This is believed to be the result of extensive erosion and deposition during or shortly after the Middle Holocene interval (Rosenthal et al. 2007:153). Middle Holocene or Lower Archaic sites are associated with notched and stemmed dart points, including Lake Mohave, Silver Lake, and Pinto styles. Early Holocene milling equipment persists (particularly in the foothills) but in marsh, riparian, and estuarine settings, mortars and pestles appear as early as 6,000 cal. B.P., possibly signaling increased investment in a more sedentary lifestyle (Rosenthal et al. 2007:154; Rosenthal and Meyer 2008:63). Early Period (4400 to 2450 B.P.) In the Late Holocene, the archaeological record increases significantly. The so called Early Period or Windmiller Pattern is widespread throughout the Delta and northern San Joaquin Valley. Sediments containing Early Period deposits are typically orange-brown, compacted soils lacking organic material (Soule 1976:12). Although the origin of this pattern is unknown, the sophisticated material culture and technologies of the Early Period suggest a fluorescence stemming from an earlier cultural pattern (Fredrickson 1994:44). 25 The Early Period mortuary complex is characterized by ventrally extended burials with a westerly orientation and numerous grave goods, including extensive use of red ochre. Diagnostic shell artifacts include Haliotis ornaments corresponding to Gifford’s (1947) types K, Q, and S and the first appearance of Olivella biplicata shell beads (Rosenthal et al. 2007:155). The latter include Bennyhoff and Hughes’ (1987) types B and L Olivella beads. Lithic technologies include large stemmed and leaf-shaped projectile points, polished stone atlatl spurs, ground slate pins, steatite pipes and beads, and well-made plummet style charmstones of exotic and local material sometimes with shell bead appliqué. Quartz crystals are also common in Early Period assemblages as are baked clay balls and ‘pecans’ with impressions indicating use of fine twisted cordage and twined basketry (Moratto 1984:203; Rosenthal et al. 2007:155). Bone artifacts include awls, needles, plain bird bone tubes, and fishing gear, such as bone hooks, gorges, and spear heads. Milling equipment includes handstones and millingslabs as well as mortars and pestles. The various aspects of the Early Period record indicate these people lived in large sedentary groups, practicing a logistically structured Early Period subsistence pattern (sensu Binford 1979, 1980). The presence of exotic trade goods also indicates these populations were part of a regional trade network. Obsidian sources employed during the Early Period include eastern Sierra sources (e.g., Bodie Hills, Casa Diablo, Coso, and Mount Hicks), North Coast Range (e.g., Napa Valley and Borax Lake), and southern Cascades (e.g., Tuscan) (Rosenthal et al. 2007:155). As noted above, Olivella shell beads make their first appearance in the study area during the Early Period, indicating trade with Southern California coastal groups (Hughes and Milliken 2007:268-269). Several Early Period sites are located in the study area. These are the Old Bridge Site (CAL-237), the Windmiller Mound (SAC-107), the Blossom Mound (SJO-68), and the Erich Mound (SAC-168). The Denier Mound (SAC-67) is also reported to have an Early Period burial-related component (Jerald Johnson, personal communication 2010). The Middle Period (2450 to 900 B.P.) Middle Period sites are more numerous and better understood than Early Period deposits. The Middle Period, Cosumnes Culture, or Berkeley Pattern, is a suite of diagnostic cultural traditions most 26 commonly found in the Delta, Stockton, and San Francisco Bay regions (Moratto 1984:210-211). Middle Period deposits are typically a well-developed brown midden containing hearth features, fire-fractured rock, storage pits, and house floors indicating Middle Period sites were intensively occupied (Bouey 1995:348-349; Rosenthal and Meyer 2008:68; Rosenthal et al. 2007:156; Soule 1976:12). The Middle Period mortuary complex is characterized by flexed burials with variable orientations and a paucity of grave goods. A few cremations have also been recorded. Inhumations are sometimes accompanied by animal bones and animal burials have also been recorded. Diagnostic shell artifacts include Haliotis type J, K, and U ornaments (Gifford 1947) and class C, D, F, and G Olivella shell beads (Bennyhoff and Hughes 1987). Other diagnostic ornaments include bi-pointed, flat, and cylindrical slate pendants, steatite rings, flat beads, and ear spools, and biotite, actinolite, and hematite pendants (Bennyhoff 1972 in Elsasser 1978:40; Rosenthal and Meyer 2008:69). Other diagnostic artifact types include heavy, concave-base non-stemmed dart-sized projectile points with distinctive diagonal flaking, atlatl hooks of bone and antler, fishtail and asymmetrical spindle-shaped charmstones, and baked clay cooking balls (Bouey and Waechter 1992:11; Fredrickson 1994 [1973]:44-45; Moratto 1984:209-211). The Middle Period is also marked by a growing emphasis on bone tools, whistles, tubes, spatulae, and bi-pointed implements. Items made of mammal bone are noticeably more abundant than those made of bird bone (Fredrickson 1994 [1973]:44; Rosenthal and Meyer 2008:73). Milling equipment includes wooden mortars and both bi-pointed and flat-end pestles, and less frequently, handstones and millingslabs. The beginning of the Middle Period roughly corresponds with the onset of cooler and wetter environmental conditions (Rosenthal and Meyer 2008:64). Large sedentary communities found on levee ridges and other elevated landforms with extensive cemeteries and smaller satellite villages characterize this period (Rosenthal and Meyer 2008:68 and the sources therein). Economies appear to be focused on a broad spectrum of plant and animal resources, many of which could be seasonally exploited for storage or exchange. Specialized tools and gear are prevalent, including fishing gear, such as harpoon heads, hooks, net weights, and mesh gauges, and fabricating implements, such as elk antler wedges, bone “shaft wrenches,” bone awls, and stone drills. 27 Some have speculated that some attributes of the Middle Period reflect the spread of Utian speaking groups from the Bay Area (Moratto 1984:211). Evidence of contemporaneous Windmiller cultures is found along the western and southern edges of the Delta and along streams and axial marshes of San Joaquin and Merced counties. These circumscribed Windmiller cultures continue until sometime between 800 and 1000 years ago (Rosenthal et al. 2007:156). Other supporting evidence may lie in the shift of obsidian away from eastern Sierran (e.g., Bodie Hills) sources to North Coast Range (e.g., Borax Lake and Napa Valley) sources (Rosenthal et al. 2007:157). Similarly, shell bead and ornament trade shifts away from southern California sources to include more Bay Area and central coast material (Heizer 1951:94-95 as cited in Ragir 1972:136; Rosenthal and Meyer 2008:69). Study area sites with Middle Period deposits include the Johnson Mound (SAC-6), the Souza Mound (SAC-42), the Denier Site (SAC-67), SAC-133, SAC-142, and the Stone Lake Site (SAC-145). Faunal assemblages from three of these sites, SAC-42, SAC-67, and SAC-133, are used in this thesis. The Late Period (900 to 150 B.P.) The Late Period is also known as the Augustine Pattern, Hotchkiss Culture, and Emergent. Late Period deposits are characterized by black, greasy midden (Soule 1976:12). Many Late Period sites identified in the study area are located on high ground near watercourses. Late Period archaeological assemblages often display regionally specific characteristics indicating a coalescence of previous Middle Period traits with new technological developments, trade goods, and economic patterns (Fredrickson 1994 [1973]:45). The Late Period is typically divided into two phases: Phase I (700 to 400 B.P.) and Phase II (400-150 B.P.). For the purposes of this study, the Late Period will be discussed as a single cultural period and distinctions between the phases will only be made when significant differences exist. Mortuary traits associated with the Late Period in the study area include tightly flexed burials, and cremations often displaying preinternment grave pit and grave good burning . Utilitarian objects such as hunting equipment, fishing gear, mortars and pestles (sometimes “killed”), and wealth objects such as shell beads and ornaments are often included (Rosenthal et al. 2007:158). In Phase I, cremations appear to be reserved for high status individuals based on the differential distribution of grave goods. In Phase II, 28 cremation is the general practice for all interments. Shell bead patterns in Phase I include incised, trapezoidal and “big head” or “banjo” Haliotis ornaments types N, O, K, and S (Gifford 1947) and class E, H, K, and M Olivella shell beads (Bennyhoff and Hughes 1987). Clamshell disk beads are introduced in Phase II and quickly eclipse Olivella forms. Additional Phase II shell beads include Tivela tube and Dentalium beads along with magnesite disk beads. In the late Phase II period, European glass trade beads become commonplace. Changes in lithic technologies and the baked clay industry also occur. The bow and arrow is introduced sometime between 1100 to 700 cal. B.P. (Rosenthal and Meyer 2008:71). The earliest arrow points were contracting stem Gunther-barbed series projectiles. These were followed by Stockton Serrated series (Phase I) and Desert Side-notched (Phase II) points. Stockton Serrated points represent a local invention, morphologically dissimilar to other Californian arrow point series (Rosenthal and Meyer 2008:71). Another in situ Late Period development was the incipient pottery tradition termed Cosumnes Brownware (Johnson 1990; Kielusiak 1982). This ceramic tradition has a restricted distribution along the Cosumnes River and appears to have been manufactured from local clay sources (Johnson 1990:156). Examples of this pottery have been identified in assemblages from along the Cosumnes River (e.g., SAC-6, SAC-67, SAC-107, SAC-127, SAC-265, SAC-267, and SAC-329) (Johnson 1990:146). Characteristic examples include rolled, coiled, and pinched clay fragments as well as finished body, base, and rim sherds (Johnson 1976:301-319, 1990:146). Animal, bird, and human effigies and hand molded bowls sometimes displaying fingernail incising and punctate decoration are other common examples (Johnson 1990:148). Diagnostic Late Period bone and antler artifacts include serrated fish harpoons and incised patterned bird bone tubes and whistles. Antler or bone toggle harpoons and composite bone fish hooks are diagnostic of Phase II. Numerous complete and fragmentary bone awls indicate the manufacture of coiled and twined basketry, netting, and other textiles (Rosenthal et al. 2007 and the sources therein). Other diagnostic Late Period artifacts include formed mortars and pestles, including flat-bottomed mortars, cylindrical pestles, bi-pointed wooden mortar pestles, flanged steatite pipes, and steatite and baked clay ear spools (Fredrickson 1973:45; Moratto 1984:212-213; Rosenthal et al. 2007:158-159). 29 There is a slight shift in exchange patterns for certain trade items during the Late Period. Raw materials rather than finished items increase in frequency. For example, obsidian cobbles and large flake blanks from the Napa Valley have been found in several lower Sacramento Valley sites (Fredrickson 1994 [1973]:45; Rosenthal and Meyer 2008:76; Rosenthal et al. 2007:159). Napa Valley obsidian continues to be the major source but small amounts of Bodie Hills begin to appear again in the record (Rosenthal and Meyer 2008:78, 79). Some deposits north of the Delta exhibit clam shell manufacturing residues, but not those in the immediate study area. Olivella and Haliotis shell from southern California and the Central Coast continued to be traded along with other previously unknown commodities from distant places, such as Dentalium from Pacific Northwest and European metal items and glass beads. Late Period sites abound in the study area. Examples include the Hollister Mound (SAC-21), King-Brown site (SAC-29), Mosher Site (SAC-56), Booth Mound (SAC-126), Augustine Site (SAC-127), Kadema Site (SAC-192), Whaley Site; (SAC-265), Blodgett site (SAC-267), and Georgiana Slough Site (SAC-329). Several Late Period sites are also ethnographic known villages. These include Sama (SAC-29), Amuchamne aka Umucha (SAC-126), and Kadema (SAC-192) (Bennyhoff 1977:58, 83, 105, 165). Faunal assemblages from SAC-29, SAC-267, and SAC-329 are used in this study. Ethnographic Context Ethnographically, the study area was inhabited by the Plains Miwok and Valley Nisenan. Information for the Plains Miwok and Valley Nisenan is limited and is derived in part from geographically separate but linguistically related groups such as the Sierra Miwok and Hill Nisenan (e.g., Barrett and Gifford 1933; Beals 1933; Kroeber 1925, 1929; Levy 1978; Littlejohn 1928; Ritter and Schultz 1972; Wilson 1972; Wilson and Towne 1978). In general, inhabitants of the study area lived in permanent yearround settlements along waterways. They practiced intensive seed gathering combined with hunting and fishing within defined territories (see Figure 3). Grassland burning was practiced by both study area cultures and surrounding groups (Levy 1978:402; Matson 1972:43). 30 Plains Miwok The Plains Miwok represent a linguistic amalgamation of many autonomous socio-political groups or tribelets (Bennyhoff 1977:15; Kroeber 1962:29). They spoke one of the five Eastern Miwok languages of the Utian language family (Levy 1978:398). Linguistic and archaeological evidence suggest that the ancestors of the Plains Miwok have resided in the Delta region for at least 4400 years (Golla 2007:76). Population estimates between 11.1 and 57 persons per square mile have been proposed for the Plains Miwok, with the highest density reflecting areas along watercourses (Baumhoff 1963:219, 226; Johnson 1976:39). Cosumnes Brownware is a unique tradition attributed to Late Period Plains Miwok groups (Johnson 1990:148). The general boundaries of Plains Miwok extended from the Deer Creek/Sloughhouse Pacific Ocean Figure 4. Ethnographic Territories (after Bennyhoff 1977, Map 2). 31 vicinity on the north to the lower banks of the Mokelumne River on the south, and from the edge of the Sierra Foothills on the east to the edge of the Yolo Basin on the west. Valley Nisenan The Nisenan, or Southern Maidu, are the southernmost linguistic group of the Maidu Penutian language family (Wilson and Towne 1978:387). Three Nisenan dialects are recognized Northern Hill, Southern Hill, and Valley Nisenan. The Valley Nisenan lived on the southwestern outskirts of the larger Nisenan territory and is the group most associated with the study area. Valley Nisenan territory extended from the Sacramento River Pocket Area northward to the crest of the Sierras (see Figure 4). The southern boundary is typically believed to be somewhere near SAC-29 (Johnson and Farncomb 2005:63; Matson 1972:40). Pre-contact population estimates for Nisenan range from five to seven people per square mile (Matson 1972:44). Ethnographic data on the Nisenan is drawn primarily from foothill groups, however, it has been suggested that Valley Nisenan lifeways resembled those of the Plains Miwok with whom they shared similar surroundings. The following description will account for the subsistence patterns of both groups. Only striking differences or specific references to one group will be noted. Ethnographic Subsistence Patterns The Plains Miwok and the Valley Nisenan seasonally exploited various plant and game resources within their territory (Levy 1978:402; Matson 1972:41; Wilson and Towne 1978:389). Archaeological deposits in the study area indicate year-round occupation and use of various seeds, acorns, terrestrial game, waterfowl, and fish (Barrett and Gifford 1933; Bouey and Waechter 1992; Craw 2002; Johnson 1976; Milliken 1995; Schulz 1981; Soule 1976; Wilson 1972). Many of these resources provided both sustenance and raw materials for various utilitarian, decorative, and ceremonial objects. Fish The diversity of fishing technologies in study area collections indicates the importance of fishing in the diet. Important fish listed in ethnographic accounts include salmon, sturgeon, and lamprey (Barrett 32 and Gifford 1933:187-190; Wilson 1972:34-35) but archaeological evidence indicates that other species were of even greater significance (e.g., Sacramento perch, Sacramento sucker, and thicktail chub [Lightfoot and Parrish 2009:327-329; Rosenthal and Meyer 2008:72, 74; Stevens and Zelazo 2010]). Ethnographic accounts indicate that fishing was both an individual and communal activity performed from riverbanks or tule rafts. Fishing technology included clay ball and stone weighted nets, dip nets, weirs and seines (especially in the marshes), basketry traps, toggle harpoons, bi-pointed fish hooks, spears, and poison from buckeye (Aesculus californica) and soaproot (Chlorogalum pomeridianum) (Barrett and Gifford 1933:187-190; Levy 1978:403; Wilson 1972:34-35; Wilson and Towne 1978:389390). Interestingly, there is no mention of fishing weirs being used along the lower reaches of the Sacramento River although weirs were used in upper reaches of the Sacramento River. Weirs would have been essentially useless in the lower river because it is too wide, deep, and the flow too heavy for weirs to be effective. Large fish (e.g., salmon and sturgeon) were usually filleted and eviscerated when caught and then eaten fresh or dried. Salmon roe was also eaten fresh or dried while salmon vertebrae were sometimes pounded and eaten raw (Barrett and Gifford 1933:190; Lightfoot and Parrish 2009:326). Drying was accomplished either in the open air or by smoking (Barrett and Gifford 1933:140; Wilson 1972:35). Dried fish were transported back to villages and stored in baskets. Dried fish was eaten in chunks, strips, or pounded into a meal that was sometimes made into cakes. Dried fish was also mixed with acorn mush and broiled on sticks over a fire (Barrett and Gifford 1933:139). A mixture of dried salmon roe, pine nuts and salmon flour is recorded as being traded for salt and clam shell disk beads from the coast (Lightfoot and Parrish 2009:326). Smaller fish were eaten when caught or dried whole. Smaller fish were also wrapped in plant leaves and steamed in earth ovens or roasted whole in ashes (Barrett and Gifford 1933:138; Levy 1978:405; Wilson 1972:35). Fish was also used as a trade item with foothill groups (Davis 1961:35; Wilson 1972:35). 33 Birds As with fish, various types of nets were employed to catch birds, particularly ducks. Plains Miwok reportedly used two kinds of duck nets. The first was a weighted net that was pulled down over the ducks as they fed in shallow water; acorns were sometimes used as bait. This net was about six feet wide and 40 feet long (Barrett and Gifford 1933:186). The second type of net was designed to catch ducks and geese as they approached the water (Kroeber 1925:410). It was set between two notched poles and was left to lie loose in the water. As the birds came into land, the net was pulled up by a watcher hiding on the bank, causing the birds to become trapped as they flew into the net. There are no accounts of decoys being used to hunt ducks in the study area groups, but they were used by other Central Valley groups (Lightfoot and Parrish 2009:330). Nets were also used to hunt quail in the foothills and by the Nisenan to capture robins and doves (Barrett and Gifford 1933:185; Wilson 1972:36). Other birds were hunted using arrows, snares, traps, and nooses with acorns occasionally used as bait (Barrett and Gifford 1933:183-187; Wilson 1972:36; Wilson and Towne 1978:390). Geese were sometimes hunted at night, with a small fire built to attract them. Woodpeckers were also hunted at night by capturing them in their roosting cavities (Barrett and Gifford 1933:186). Birds were typically cooked whole in the ashes or covered in mud and baked (Barrett and Gifford 1933:138; Wilson 1972:36; Wilson and Towne 1978:389). Picking or skinning often occurred after cooking through the removal of a baked mud covering. Bird meat was not known to be dried (Wilson 1972:36). Other birds, such as raptors, flickers, woodpeckers, and magpies were trapped primarily for their feathers (Lightfoot and Parrish 2009:332). Bird bone was used for many ceremonial and decorative implements. These include whistles, tubes, skewers, earrings, hair pins, and awls. Incised bird bone whistles and tubes are well documented ethnographic items. Plains Miwok in the Cosumnes region employed an openwork design while that of the Sacramento Valley Nisenan (i.e., Sutter District) used a multiline style (Bennyhoff 1994:71-73). Feathers were employed for arrow fletching, decoration, and clothing, particularly for ceremonial items such as dance headdresses, aprons, and belts. Duck and goose down was also used for blankets and robes 34 (Lightfoot and Parrish 2009:330). Blankets of duck feathers and feather capes have also been recorded. Belts or ropes of woodpecker scalps sewn onto buckskin and decorated with Olivella shell beads were a highly valuable garment and medium of exchange (Barrett and Gifford 1933:221). Mammals Three species of artiodactyls were used by inhabitants of the study area: tule elk, pronghorn, and black-tailed deer. All three were hunted individually and communally, with tule elk and pronghorn being identified as particularly important (Levy 1978:403). Hunters wore tight fitting grass caps or deer headdresses fashioned from the skull and skin of these animals (Barrett and Gifford 1933:178-182; Wilson 1972:34). Hunting blinds were baited with mistletoe for deer hunting and disguises made of wild cucumber for hunting pronghorn (Barrett and Gifford 1933:180). Communal deer hunts took place in the fall, when deer congregated for the rut (Lightfoot and Parrish 2009:335). Dogs were also used to track wounded and “very fat” deer (Barrett and Gifford 1933:180). Annual fall burns were important for not only fostering important economic plant species, but also for creating abundant artiodactyl habitat (Levy 1978:402; Mason 1972:43). Artiodactyl butchering depended on the distance between the kill site and village. Ideally the entire carcass was taken back to camp for processing, although certain entrails might be removed and cooked at the kill site (Barrett and Gifford 1933:181; Wilson 1972:34). Brains, hides, and sinew were typically taken back to occupation sites but entrails may be used as bait for smaller animals. Bones were cracked and cooked for marrow or retained for tools. Artiodactyl bone and antler were widely used for utilitarian implements. Of these, limb bones and metapodials, often referred to as “cannon bones,” were used for awls, hair pins, “daggers,” and gaming pieces (Barrett and Gifford 1933:229; Gifford 1927:160; Wulf 1997:173-197). The use of artiodactyl ulnae and radii for awls has also been reported (Gifford 1940:161; Wulf 1995:182, 189). Antler was used to make harpoon toggles, fishhook barbs, wedges, and chisels among other tools (Gifford 1940:166; Wulf 1995:140). Artiodactyl hide was used for clothing, matting, house coverings, and as trade items (Barrett and Gifford 1933:181; Wilson 1972:34). 35 Artiodactyl meat was either cooked or dried for storage, and the meat was shared among hunters, their families and neighbors often in prescribed reciprocal relationships (Barrett and Gifford 1933:181; Wilson 1978:389). Although hunters were appreciated, greater prestige was held for those who had specialized knowledge (Barrett and Gifford 1933:181). This included individuals who produced hunting equipment and utilitarian items such as pipes, baked clay objects, cordage, or luxury goods [e.g., feathered textiles, shell bead ornamentation, ceremonial garb, and incised bird bone tubes (Bennyhoff 1977:11, 13; Bouey 1995:25)]. Beaver were hunted at their dens, killed by being clubbed, or shot with bow and arrow (Barrett and Gifford 1933:182). Beaver incisors are often found in archaeological deposits and were presumably used as gouges and chisels (Gifford 1940:167, 184; Wulf 1997:136). Black-tailed jackrabbit and desert cottontail were procured either individually by clubbing or bow and arrow, or in groups by means of a “rabbit drive” (Barrett and Gifford 1933:182; Wilson 1972:35). Both Plains Miwok and Valley Nisenan drove jackrabbits into nets that were stretched into a V-shape. Successful drives could procure hundreds of jackrabbits. Lagomorphs were skinned before cooking and cooked directly on coals or encased in mud and baked in a fire (Barrett and Gifford 1933:138; Wilson 1972:36). Rabbit skin blankets were woven from strips of seasoned cottontail or jackrabbit fur, a single blanket requiring the skins of approximately 40 animals (Wilson 1972:35). Western gray squirrel and California ground squirrel were also eaten. They were shot with bow and arrow or captured by dogs and cooked directly on coals (Barrett and Gifford 1933:183). Other mammals are mentioned in study area ethnographic accounts. Rats (most likely woodrats) and mice are likewise recorded as food. These were usually dried then pounded in to a meal (Wilson 1972:36). Gophers were roasted in hot ashes (Beals 1933:349). Wilson and Towne (1978:389) report that “wildcats and California mountain lions were hunted for food and their skins,” by the Nisenan and Levy (1978:403) claims that the Plains Miwok “never ate grizzly bear, black bear, fox or wildcat.” Black bears were hunted and eaten by Nisenan people, but since the study area is outside the black bear’s natural range, valley populations would have had little opportunity to exploit them. California grizzly bear were found in the study area, but were greatly feared and rarely hunted (Wilson and Towne 1978:389). Dogs are 36 frequently mentioned in ethnographic accounts for hunting bear, deer, fox, lagomorphs, and squirrels, and were also eaten at times (Barrett and Gifford 1933:270; Lightfoot and Parrish 2009:334-337). Other Fauna The western pond turtle was another important source of meat. Turtles were killed with a stone and roasted in their shells (Barrett and Gifford 1933:139; Lightfoot and Parrish 2009:329). Freshwater mussels and grasshoppers comprise two invertebrates exploited as food (Barrett and Gifford 1933:192; Wilson and Towne 1978:389). Freshwater mussels were available in many streams and rivers and were cooked under a layer of sand, burning grass, or brush (Barrett and Gifford 1933:139). Freshwater mussel shells were widely employed as spoons, but only the Nisenan used them as knives (Lightfoot and Parrish 2009:323). Beads made of freshwater mussel have also been found in local archaeological collections (Gifford 1947:30). Summer grasshopper drives were practiced by both Valley Nisenan and Plains Miwok groups (Barrett and Gifford 1933:190; Wilson 1972:36). Pits would be dug in an open grassy field into which grasshoppers would be driven. Once captured, grasshoppers were roasted in earth ovens or parched in openwork baskets then dried, crushed into a meal, or stored for winter consumption (Barrett and Gifford 1933:190; Wilson and Towne 1978:390). Summary The study area environment has experienced many changes since the arrival of humans 11,000 to 13,500 years ago. As warmer Holocene temperatures replaced those of the Pleistocene, sea levels rose inundating hundreds of feet of California shoreline creating the San Francisco Bay and Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. By approximately 6000 B.P., the Delta stabilized and was permanently settled by human groups. Archaeological investigations reveal that by 4400 B.P., resident populations were marked by territorial circumscription, highly developed mortuary practices, elaborate material cultures, and longdistance trade. The establishment of local culture history dominated archaeological research in the study area until approximately thirty years ago when processual studies shifted focus onto the interplay between landscape evolution, human behavior, and the structure of the archaeological record. 37 The paleoenvironmental record of the study area reveals that the Late Holocene was generally cooler and wetter than the Middle Holocene, marking the onset of the modern Mediterranean climate. When examined on a fine grained scale, however, variations in Late Holocene climate become more apparent, with the dry MCA and the wetter LIA, distinguishing the Late Period. These events are recognized in proxy data which indicate significant changes in rainfall and water flow out of the Sacramento-San Joaquin drainage during the last 2,000 years. Drought conditions prevailed during the MCA in the late Middle Period and first 300 years of the Late Period. Traditional responses to drought and economic instability include mobility, diversification, storage and exchange (Halstead and O’Shea 1989; Schwitalla 2010:20). Yet, archaeological evidence indicates that the MCA occurred at a time when study area societies already possessed complex trade, socio-political, and mortuary traditions. Permanent villages, ceremonial centers, storage facilities (granaries), and large cemeteries, indicate the presence of dense populations. Given that much of the study area was uninhabitable wetland or treeless savannah, mobility was limited and storage and exchange already practiced. Faced with such restrictions, changes in technological organization and subsistence patterns may have instead offered the only solution. Instead, technological innovations (e.g., toggle harpoons, pottery, and the bow and arrow) are an important aspect of the Late Period. Whether there is comparable evidence for subsistence intensification from the Middle Period to the Late Period when climatic conditions changed is less clear and explored in greater detail in the remainder of this study.