Policing for Democracy or Democratically Responsive Policing?

advertisement

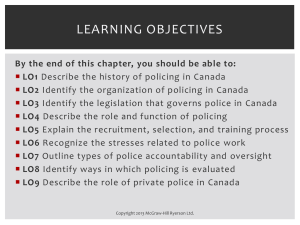

Policing for Democracy or Democratically Responsive Policing? Examining the Limits of Externally Driven Police Reform Andy Aitchison and Jarrett Blaustein University of Edinburgh School of Law ABSTRACT This paper engages with literatures on democratic policing in established and emerging democracies and argues for disaggregating democratic policing into two more precise terms: policing for democracy and democratically responsive policing. The first term captures the contribution of police to securing and maintaining wider democratic forms of government, while the second draws on political theory to emphasise arrangements for governing police actors based on responsiveness. Applying two distinct terms helps to highlight limitations to external police assistance. The terms are applied in an exploratory case study of fifteen years of police reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). The paper highlights early work securing the necessary conditions for political democracy in BiH but argues that subsequent EUdominated interventions undermine responsiveness. A recent UNDP project suggests that external actors can succeed in supporting democratically responsive policing where they do not have immediate security interests at stake. KEYWORDS Policing; democracy; responsiveness; Bosnia and Herzegovina; EU Introduction Democratic policing has been defined and redefined by scholars, practitioners and reformers (e.g. Bayley 2006; OSCE 2008; Pino and Wiatrowski 2006). Limited consensus exists on what makes policing ‘democratic’ and how this is best achieved, especially when pursued through externally-driven reform. In translating democracy into prescriptions or evaluative schemes for police services and police governance (e.g. Marenin 1998, Jones et al 1996, Marks 2003), or into lists of values to inform police reform (OHR 2004), the distinction between policing which supports the establishment or maintenance of democracy, and the specific arrangements for democratic governance of police services is overlooked or understated. We elaborate on this distinction, then draw on supporting material from Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) to identify international interventions associated with policing for democracy and to highlight structural conditions associated with liberal state-building which obstruct the development of democratically responsive policing. We argue that, while external actors may be well placed to 1 support policing for democracy in divided, post-conflict or post-authoritarian contexts, democratically responsive policing requires greater sensitivity to locally defined needs, and is undermined when external interventions are driven by the needs, priorities and interests of sponsors. Contrasting the interventions on the part of the EU, which has strong security interests in the Western Balkans, with the UN Development Programme, underlines this point. Our reading of work on policing and democracy in established liberal democracies (e.g. Bradley et al 1986; Jones et al 1996, Loader 2002) suggests that where the democratic nature of the polity is taken for granted, analyses neglect the role of the police in establishing and maintaining a democratic polity in favour of the mechanisms which govern police services1. Work on post-colonial contexts (Bayley 1969, Marenin 1982) and post-authoritarian states in Africa (Marks 2003), Australasia (Goldsmith and Dinnen 2007), Europe (Ryan 2009) and South America (Hinton 2008) cannot take democracy for granted. This produces more even, if not always explicit, attention across policing for democracy and democratic governance of the police. As the rhetoric of democratic policing within established democracies is critiqued (Manning 2010 21-22), a strong body of work associates the ‘export’ of democratic policing with a wider agenda aimed at aligning governing processes, institutions and structures in weak states with the preferences and priorities of strong external actors (Bowling and Sheptycki 2011; Ellison and Pino 2012; Ryan 2011). We seek to salvage something from democratic policing to provide reformers with a framework for police-support in new or emerging democracies. As an example of a country experiencing intensive and extensive international intervention in police reform, BiH illustrates challenges of, and limits to, externally driven programmes of democratization. As an exploratory case study, BiH is used to illustrate the application of the terms policing for democracy and democratically responsive policing and to assess their value in identifying the limitations of external police assistance. Aitchison spent the summers of 2004 and 2005 in BiH, conducting interviews with participants in, and observers of, criminal justice reform and reconstruction (see Aitchison, 2011, pp. 8-12). In this period the Police Restructuring Commission was established and made its recommendations, and negotiations on restructuring took place between the main political parties under the oversight of Bosnia’s international overseer, the High Representative2. After an initial field visit in 2010, Blaustein spent 3 months of 2011 embedded in the Sarajevo office of a multi-lateral development organisation active in the field of police reform. Documentary output from the main participants in police reform has also been utilised. In what follows, we examine the role of police in establishing and maintaining necessary conditions for democracy. We suggest that supplementing these necessary conditions with a multi-dimensional concept of responsiveness derived from Kuper (2007) underpins police democratisation and sets useful boundaries for external intervention. 2 Police and Democracy In examining the relationship between police and democracy, we take Bayley’s definition of police as a starting point encompassing the capacity to use force, a distinction from military armed forces, and a mechanism for social or political delegation of authority to a body of people responsible for the regulation of interpersonal relations (1985: 7). We recognise that this does not cover the whole gamut of actors and actions that constitute the wider sense of policing, but our focus in the first instance rests on public or state-police3 as key to understanding the distinction between policing for democracy and democratically responsive policing. A minimalist view of democracy stresses procedural dimensions: regular and open selection of leaders; a popular franchise; and appropriate procedural safeguards. These are made meaningful by key freedoms, including freedom of the press, of association and assembly, and of expression (Parrott 1997: 4; see also Collier and Levitsky 1997: 434). These freedoms produce a capacity for public debate. A more expansive definition of democracy, indicative of consolidation, requires political power to change hands peacefully more than once (see Huntington 1991: 266), and in terms of the effective power to govern (Collier and Levitsky 1997: 444) requires major political actors and social groups to accept and utilise representative institutions to pursue political claims (Dawisha 1997: 43). Andrew Kuper’s work on global democracy develops responsiveness as the fundamental element of democracy, examining the idea across horizontal and vertical dimensions (2007: especially 103-4). While Kuper does not dismiss the value of procedures, he focuses primarily on a conceptual core of responsiveness. Vertical responsiveness expects the ‘reasonable contestations’ of citizens to generate a ‘proper response’ from those in positions of authority. This need not be simple acquiescence to the demands of a majority and responses can vary from explanation through to policy change (Kuper 2007: 104). Horizontal responsiveness describes the checks and balances between political actors and institutions. Kuper seeks to avoid a range of practical obstacles to the realization of democracy as imagined by Habermas and Goodin (Kuper 2007: 61-74). By anticipating structures where interdependent authorities need to respond to one another, building consensus and cooperation (Kuper 2007: 103), he still acknowledges the value of discourse and communication in those original schemes. As no individual actor can claim perfect knowledge, constellations of ‘knowers’ are forced into mutual responsiveness. In our exploration of the conceptualisation of democratic policing, we find that many separately conceived indicators are oriented towards responsiveness. 3 Policing for democracy Bayley’s early work on police and political development sets out the case for linking police activity and political regimes. Police are not simply passive agents shaped by their political environment but help shape that environment and the system of government (Bayley 1969: 12-13, 409). Minimum standards of police practice are necessary, if not sufficient, to support political democracy. The police organisations required for these tasks need not be democratically responsive in the sense defined below and we argue that the limited goal of policing for democracy can feasibly be driven by external actors. Policing for democracy is policing which does not damage, but actively supports, the development of the core elements of democracy and democratic consolidation. In terms of practical implications, policing for democracy calls for a combination of restraint and positive obligations rooted in protecting the exercise of political freedoms. Restraint means avoiding actions designed to intimidate people exercising political rights (e.g. political campaigning, attending political meetings, meeting constituents, media reportage). Likewise, it requires that police do not react with oppressive force to non-violent political and community gatherings. While police need not be excluded from party membership, this ought not to influence their professional conduct. As an extension of this, police officers should not support political actors seeking to undermine democratic institutions by criminal or extra-constitutional means. Positive obligations encompass the protection of electoral processes, securing voters against intimidation and obstruction and protecting ballot boxes and election counts. Following elections, police play a role in ensuring that political representatives are safe to carry out their role. Where there are attempts to subvert normal democratic processes, or there are extra-constitutional or violent attempts to pursue political claims, then policing for democracy requires that these are investigated in cooperation with the appropriate prosecutorial or judicial authorities. More broadly the police are obliged to enact decisions of legitimately constituted judicial and prosecutorial authority, through the execution of arrest warrants and conduct of investigations. Finally, policing for democracy requires the more general maintenance of peace and order which is necessary for free and open political exchange. These restraints and obligations help to ensure that institutions act in their legally constituted manner, that there is a free and open line for communication between citizens and political representatives, and that public space is available for political debate. Elias identifies the economic and social opportunities created by the consolidation of the means of force and subsequent internal pacification (1994: 419-420). The relative pacification of police and their direction towards providing an equitable minimum of security is necessary, if not sufficient, for free political action. This fits with Marenin’s principle of ‘general order’ in his criteria of democratic policing, meeting a ‘minimal expectation of 4 stability, order and routines which allows people to predict what they are able to do’ (1998: 171). We isolate this general order, along with a liberal principle of equal application, from democratic policing in order to define the more specific practice of policing for democracy. The concept of policing for a democracy is about what police do and how they do it, and carries no assumptions about the governing structures which produce this. For example, in a post-conflict environment, where police power and authority are strongly contested by former parties to the conflict, achievement of restraint and fulfilment of obligations identified above may be maximised by strong direction and oversight by external actors. Where this is accompanied by strong investigative powers and levers to ensure that domestic law and regulations are used to respond to abuse of power, space can be created for democratic political forms to develop in the wider polity. Democratically Responsive Policing While policing for democracy is a necessary but insufficient platform for a democratic polity, and may be imposed from outside, it falls short of democratically responsive policing. With particular reference to three key texts in the democratic policing canon (Jones et al 1996; Manning 2010; Marenin 1998), we identify two prior qualifications for a democratically responsive police service that focus on equity of policing and the capacity to deliver a minimum level of service and security. The principle of equity and police capacity to provide a certain minimum threshold of security were identified in the discussion of policing for democracy and encompass the values of service delivery, efficiency and effectiveness highlighted by Jones et al (1996: 191) and Marenin (1998: 169). We see the elements of policing for democracy as a necessary prerequisite for democratically responsive policing. Beyond these elements, much of the democratic policing literature points towards the value of responsiveness and we argue that a focus on responsiveness achieves a greater conceptual clarity. We present this schematically in table 1, below, and explain the reasoning and the impact on our understanding of democratically responsive policing in the remainder of the section. TABLE 1. Democratic policing and responsiveness <<INSERT TABLE ONE AROUND HERE>> Responsiveness is omnipresent within the literature on democratic policing (e.g. Bayley 2006; Jones et al 1996). Jones et al include it as their third most important criterion, expecting police to be ‘responsive to some expression of the views of the public’ on the principled basis ‘that government should reflect the wishes of the people’ (1996: 191). Following Kuper, responsiveness is not simply acquiescing to a generally expressed will. Rather, ‘responding’ can mean refuting, with reason, public demands. Police and their governors may be called to 5 ‘respond’ to a wide range of individuals, groups and institutions (for a discussion of the role of ‘reasons’, see Loader and Walker 2007: 227 ff.). We subsume a number of other criteria identified by Jones et al, Manning and Marenin as dimensions of a ‘headline’ concept of responsiveness. The distribution of power speaks directly to Kuper’s sense of horizontal responsiveness between a set of actors and institutions, none of whom can claim perfect knowledge. There are various mechanisms to distribute power. Jones et al focus on governing structures (1996: 188). Manning favours competition, and while his point risks getting lost in his ensuing discussion of the blurring of police and military in contemporary wars (2010: 67-68), competition- and market-based policies seek to promote responsiveness to citizens defined as a consumer (Clarke et al 2007). Jones et al identify three further dimensions that contribute to responsiveness: information, redress and participation. Information underpins other democratic criteria (1996: 192) and promotes responsiveness in two ways: the publication of information is as a stimulus for citizens, groups and institutions to present preferences to police who must then respond; secondly, providing information can be a reasonable response. This may not require a change in policy, but requires police to articulate what they are doing and why. Jones et al have a broad notion of redress, which starts from the democratic right to remove people from public office, but encompasses responding to complaints through appropriate investigation and compensation (1996: 192). Mechanisms for redress allow the public to express their discontent with particular police actions and call upon the police to apologise and commit to behavioural change. Finally participation, the lowest priority in Jones et al’s criteria, is a stimulus demanding a police response. Manning anticipates a responsive police service by incorporating reactions to citizen complaints (i.e. calls for service) in his criteria (2010:66); Marenin, using the term ‘accessibility’, requires police to respond to citizens’ requests for help (1998: 169). Manning and Marenin both include a criterion of accountability, whereby police ‘must accept that they have to explain themselves… to outsiders who pay for their salaries, supply their resources and suffer the consequences of their work’ (Marenin 1998: 170, see also Manning 2010: 68). Marenin captures the vertical response required to citizens as tax payers and citizens as ‘the policed’, but horizontal responsiveness requires further institutional accountability to courts, legislature and executive. Finally, congruence points towards being responsive to something more difficult to pin down than individuals, groups or institutions: ‘the unique cultural, ideological and legal characteristics of a country’ (Marenin 1998: 171). This suggests a sociological concept of common consciousness (Durkheim 1938: 68) or a political theory of the general will (Rousseau 1923). In post-conflict and post-authoritarian societies in which police democratization is frequently 6 pursued, social divisions make such concepts difficult to operationalize. Nonetheless, with the various mechanisms for responsiveness included in the discussion above, one would expect an operationalized measure of congruence to correlate with the level to which these other criteria are achieved. By subsuming the various criteria of the distribution of power, competition, information, redress, participation, reaction, accessibility, accountability and, with noted reservations, congruence, into a headline concept, we hope to offer a concept of police democratization as responsiveness, built on the foundation of equity and a minimum quantity of security. This goes beyond policing for a democracy by building in conditions on how the police are governed over and above assessments of what they deliver and how equitably they deliver it. In transitional, post-conflict or post-authoritarian societies, external actors’ pursuit of democratically responsive policing is problematic. Intrusive and coercive externally-driven processes of liberal state-building and democratisation can overshadow domestic democratic institutions and processes of governance (Chandler 2010; Duffield 2007) and risk becoming the dominant stimuli shaping policing as well as shaping wider processes of political decisionmaking. This is not an outright condemnation of external interventions. The more limited concept of policing for democracy retains space for a range of external interventions designed to address, equitably, a public order security gap and to create a secure space within which open, democratic processes can take place. Having developed the distinction between policing for a democracy and democratically responsive policing, we proceed with an exploratory case study of BiH. In a context of anti-democratic and non-democratic policing4, early interventions focused most strongly on policing for a democracy. Subsequent interventions associated most strongly with the EU use the language of democratic values but undermine responsiveness to locally defined preferences. Our final subsection identifies circumstances in which external support can enhance local responsiveness. Addressing anti-democratic and non-democratic policing Immediately after BiH’s first multi-party elections, policing was evidently non-democratic and anti-democratic. After the war, this persisted with police acts of commission and omission highlighting a combination of iniquity and unresponsiveness detrimental to citizens’ fundamental freedoms. Violence against opponents of the dominant political parties was reported in particular local contexts, such as the persecution of Democratic People’s Union supporters in the North West (Human Rights Watch 1997). Freedom of movement was heavily constrained. Citizens attempting to cross the internal Inter-Entity Boundary Line (IEBL) between Republika Srpska (RS) and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH)5 were subject to extortion, intimidation and physical violence while irregular fees were collected at external borders 7 (Aitchison 2007: 333; OHR 1997). As late as 2002, it was reported that journalists from FBiH were turned back at the IEBL en route to cover Srebrenica memorial events (OHR 2002). Freedom of assembly was constrained, either through the partisan use of extreme force in responding to gatherings, highlighted when Bosnian Croat police fired on a Bajram march of Muslims in Mostar (Aitchison 2007: 332) or by the failure to prevent violence targeted at peaceful assemblies, as seen in attacks on delegations laying cornerstones of mosques in Trebinje and Banja Luka in 2001 (Amnesty International 2001a, 2001b). Other acts of omission suggested that police were failing to, or choosing not to, protect particular citizens. Failures to prevent violence against returnees or to investigate crimes against minorities discouraged those wishing to return to their pre-war homes (Amnesty International 1998; OHR 1997). The failure to protect those wishing to remain in their homes during transfers of governmental authority was manifest in early 1996 in Mrkonjić Grad, Vogošča and Grbavica (OHR 1996). Failure to provide adequate protection extended to politicians. This was seen in the stoning of a bus of Social Democratic Party delegates in Brčko in 1997 (OHR 1997)6; an unresolved attack on councillors in Srebrenica (Amnesty International 2000: 20); and the inability of municipal councillors elected by absentee voters in Foča to safely assume their responsibilities (Human Rights Watch 1998: 51-52)7. Police power and institutions had been captured by political groups in the early stages of the disintegration of Bosnia and Herzegovina (see Prosecutor v Sikirica), and this is reflected in their continuing political allegiance in the post-war period. The unresolved tension between police allegiance to a party-based structure of authority and a new context of governance saw police disregarding the legally constituted authority, with parallel forces operating in those some cantons in FBiH, RS police refusing to cooperate in policing shared territory in and around Brčko (OHR 1997), and police units bugging the President of RS, Biljana Plavšić, after a major political split in RS (OHR 1997). Finally in 2001, when the Croat Democratic Union (Hrvatska Demokratska Zajednica, HDZ) attempted to withdraw Croatdominated cantons from FBiH, there were reports of HDZ-affiliated police officers abandoning their positions (OHR 2001a, 2001b). The conduct of actual elections seems to be one area where police conduct was generally unproblematic8, nonetheless it is clear that post-war police in BiH were operating in ways which obstructed the freedoms necessary for electoral democracy. The following section looks at ways in which this was addressed through international intervention. Towards policing for a democracy Strong support for policing for democracy is evident in early UN action. Some of these have been covered in Aitchison’s earlier work, but without differentiating policing for a democracy from democratically responsive policing (2007: 331-4). The UN International Police Task Force 8 (IPTF) monitored and facilitated the entities and their commitment to provide a ‘safe and secure environment for all persons in their respective jurisdictions… with respect for internationally recognized human rights and fundamental freedoms’ (GFAP 1995: Annex 11.1). This essentially describes policing for democracy, its foundational aspects of a minimum level of security, general order, and universal, equitable provision of this for all persons. Monitoring and facilitation developed into enforcement action which included pressuring local police to investigate crimes thoroughly, regardless of the ethnicity of the victim, pressure to investigate and prosecute police misconduct, removal of police officers whose conduct, either during the war or in the post-war situation, did not fit with equitable provision of safety and security, and direct challenges to police persecution of citizens crossing the Inter-Entity Boundary Line. The process of overseeing police to challenge anti-democratic practices took longer than the initial one-year mandate, and the UN policing mandate extended to the end of 2002. Over this period, it is evident that actions to secure policing for democracy are combined with initiatives oriented towards the democratisation of Bosnia’s police. Yet the emphasis was clearly on using external oversight to ensure a particular form of policing and a particular level of service rather than on the domestic arrangements in place to govern and direct policing. The limits of external intervention In addition to work to develop policing that supported political democracy, elements of UNIPTF’s work enhance responsiveness. This included efforts to build up minority recruitment after processes of ethnic cleansing and other forms of displacement. A more diverse police force would be more likely and able to respond to the needs of a reconstructed community, including returnees9. New Policing Commissioners (in the FBIH) and Directors (in RS), were introduced under UN auspices to separate operational matters from wider policy matters. This limit to politicians’ capacity to direct policing, beyond establishing a policy framework, is part of horizontal responsiveness between institutional actors. Once policing for democracy has been established with external oversight, it can be protected in the longer term by ensuring the police do not simply respond to any one dominant party who might use this to subvert normal democratic processes. Yet although democratising the police may secure policing for democracy in the long-run, reducing the need for external oversight, there are concerns about tensions between goals of democratization and the interests of actors providing police assistance. This critique is most well-developed in respect of the EU (see e.g. Collantes-Celador and Ionnides 2011; Ellison and Pino 2012), and suggests that those donors most willing and able to commit to long term democratization projects do so, at least in part, with their own interests in mind. This 9 introduces a new pole in the landscape of responsiveness, and our concern is that this detracts from the capacity to respond to domestic actors, institutions and citizens. From 2003, when the EU Police Mission (EUPM) took over from UNIPTF, there is evidence that tasks related to policing for democracy were less of a priority. BiH had held a series of elections, involving changes of power at various levels of government10. Subsequent reforms were proposed by the Office of the High Representative (OHR), backed by the EUPM, and tied to pre-accession criteria of the EU. In these, democratic standards are an important legitimising discourse11. Twelve principles outlined by OHR fit with democratic policing as conceptualised above. For example, they stated that the police should be ‘protected from improper political interference’, perform their duties ‘in accordance with democratic values’ and operate ‘within a clear framework of accountability to the law and the community’ (OHR 2004). These principles, and the Police Restructuring Commission (PRC) set up by OHR to operationalize them, generated recommendations which included local policing plans, an independent inspection regime and a public complaints, fulfilling some of the criteria of democratically responsive police (see Aitchison 2011: 98). But the PRC also proposed policing areas which ignored existing political and territorial divisions within BiH (PRC 2005). Muehlmann (2008) gives an insider account of the process. His assessment of the dominant role of external actors resonates with our own interviews in BiH. An OHR representative identified the early advances in inter-party talks as evidence of Brussels ‘leading the agenda’ and described the approach of party representatives at the Vlašić talks of 2005 as, ‘this is something the European Union wants, let’s get on with it’ (Aitchison, Interview, Sarajevo, May 2005). Representatives of the European Commission were very clear that restructuring was required to facilitate EU interaction with BiH government and police institutions and to effectively address crimes of particular concern to the Union (Aitchison 2012: 9). Yet the proposal of cross-IEBL policing areas on the grounds of technical criteria was seen by RS politicians as a failure to recognise ‘the weight and importance of these symbolic issues’ (Mladen Ivanić in OHR 2005b). Ultimately, the necessary link between the political division of the territory of BiH and policing areas was recognised in the multi-party Mostar agreement of 2008, which postponed the question of police structures until the resolution of ongoing discussions on the constitution of BiH (Aitchison 2011: 102). External pressure to adopt structures that do not correspond to locally contested and defined preferences, is accompanied by a tendency for EU intervention to focus on specific forms of crime related to the Union’s security interests rather than those defined in BiH. This has been documented elsewhere (Aitchison 2012: 8; Collantes-Celador and Ionnides 2011: 428 ff). In relation to its member states, it makes sense that the EU should restrict its activities to these fields, where pooling state capacity may lead to more effective policing. Member states can 10 respond to this while retaining responsibility and capacity for policing local crime. In the case of a weakened state, focusing policing assistance on particular forms of crime of interest to the EU risks diverting resources required to deal with crimes of most immediate interest to the domestic population. In terms of democratically responsive policing, the gravitational force exerted by the EU provides a skewed distribution of power in which policing is overly responsive to one, external, actor. Blaustein (forthcoming) has identified elsewhere that even when the EU does not actively seek to influence policing policy, domestic assumptions about EU preferences still shape decisions12. Once policing for democracy has been established, it may require on-going external support for maintenance, but if a subsequent emphasis on democratic policing becomes linked to other reforms pursued by a powerful regional actor, there is a risk that this undermines the prospect of establishing policing which responds to domestically generated preferences and consent. By driving forcefully towards a framework for policing that abandoned the established Dayton framework of governance, against the wishes of large constituencies in BiH and their elected political representatives13, and by linking this strongly to EU accession, the police restructuring process was non-democratic. Moreover by conflating the process with democratisation, it undermined opportunities for the democratisation of existing police institutions in BiH when the process floundered on issue of cross-IEBL policing areas. The following section gives an example of work on community partnerships in BiH under the auspices of a development agency. We argue that this indicates limited circumstances in which external assistance can support the development of democratically responsive policing. Community partnerships as democratically responsive policing There is a degree of overlap between democratically responsive policing, as defined above, and certain articulations of community policing, particularly in terms local input into policing priorities and police responses to these (see e.g. Mackenzie and Henry 2009). Alongside major multilateral police reform projects, smaller scale bilateral and multilateral development projects have focused on community policing in BiH, often at a local level. Between 2003 and 2011 the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) supported municipal-level projects to develop community policing. Following on from this they assisted with the development of a national Strategy for CommunityBased Policing in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH Ministry of Security 2007), and provided support to a National Implementation Team to deliver this. Subsequent concerns about the functionality and sustainability of local community-based policing models in BiH prompted the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to pilot its own Safer Communities project in 11 2010 with the aim of improving cooperation between community police officers and municipal authorities at the local level (Blaustein forthcoming). By providing technical and financial assistance for five municipal-level ‘citizen security forums’, the Safer Communities team fostered a partnership-based approach for community safety governance that encouraged local representatives, municipal officials and senior police officers to collaborate in order to address a local security and public safety issue affecting the lives of local citizens. This addressed a lack of horizontal responsiveness whereby police were often the first point of contact for citizens raising security concerns but had limited capacity to respond effectively due to poor inter-agency cooperation. The project’s support for stray dog shelters in Zenica illustrates the capacity of community forums to deliver locally responsive policing. Stray dogs were a persistent source of insecurity in the city, but the issue had not been addressed by local authorities. Stray dogs were a persistent source of insecurity in the city, but the issue had not been addressed by local authorities due to poor coordination and a diffusion of responsibility between the police and different municipal authorities. The forum was a space in which the issue could be identified, prioritised, and responsibility for a solution agreed. UNDP seed-funding provided the financial means to design and construct shelters to house the problem animals. This example shows the value of local forums where problems and solutions are articulated and of funding that is channelled through an agency which does not have its own regional security interests14. Conclusions Our paper has disaggregated democratic policing to provide two separate concepts, policing for democracy and democratically responsive policing. We have argued that the former is a necessary platform for the attainment of the latter insofar as it accounts for the need to develop the basic institutional capacities and willingness of the police to fairly and effectively deliver secure public spaces in which democracy can develop and local needs and preferences can be articulated. By drawing on Kuper’s political theory and applying this to earlier studies of democratic policing we can employ a terminology of democratically responsive policing which places a greater emphasis on considering whose interests should shape policing and how these are best articulated. Democratically responsive policing requires a strong role for domestic actors and institutions. Our exploratory case study suggests that powerful external actors involved in liberal state-building can skew democratically responsive policing in the weak states by becoming the key stimulus for responsiveness. In BiH, the international community’s pursuit of alternative goals in the same package of measures that advocate ‘democratic policing’ has undermined opportunities to develop democratically responsive policing. Until external actors can be 12 confident in their ability insulate countries receiving police assistance from external interests, a more limited focus on supporting policing for democracy provides a reasonable framework for assistance. The UNDP pilots show the value of external assistance separated from specific political interests of donors. By supporting the formation of local forums, the Safer Communities scheme created a context in which seemingly mundane, but nonetheless important, security concerns of BiH citizens are voiced and elicit an adequate response. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Earlier versions of this paper were presented in Washington, Edinburgh, New York and Cardiff in 2011 and 2012. We would like to thank the following people for their comments, feedback and questions, which have helped shape and strengthen the final paper: Graham Ellison, Alice Hills, Liam O’Shea and Nathan Pino; Trevor Jones, Adam Edwards and colleagues at the Cardiff Centre for Crime, Law and Justice; Kirsten McConnachie and Richard Jones at the University of Edinburgh School of Law. Finally, Jarrett would also like to thank UNDP in Bosnia-Herzegovina and members of the Safer Communities team for their on-going support with his doctoral research. NOTES 1. Loader and Walker recognise the instrumental importance to democracy of particular freedoms associated with security. Yet focusing on ‘mutually reinforcing’ dynamics, where the public simultaneously constitutes and secures itself, they sideline the initial establishment of minimal democratic conditions and leave unexamined the question of external actors as guarantors of freedom (2007: 153, 163). 2. The position of the High Representative was created in the Dayton Peace Agreements of 1995. The High Representative draws his authority from those agreements, a series of UN Security Council Resolutions and the conclusions of a Peace Implementation Council. For more detail see Aitchison 2012: 5). 3. Understood as publicly funded, appointed and governed police. 4. Non-democratic serves as an antonym for democratically responsive, while anti-democratic policing is the opposite of policing for a democracy. While our exploratory case study takes an example of an emerging democracy, we anticipate that the distinction between policing for democracy and democratically responsive policing can support analyses of policing in established democracies. The miners’ strike of 1984-85 in the UK raised a number of issues of police action and competing rights in a context of a dispute on industrial policy and labour relations (McCabe and Wallington 1988). 5. Post-war BiH featured a weak central government. Most power was held by two sub-state entities, Republika Srpska and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the latter of which saw further devolution of power to 10 Cantons. The two entities were separated by a boundary line, which had the same status as other internal, administrative divisions. Special arrangements were made for the strategically important district of Brčko. For more on the structures of government in BiH, see Aitchison 2011: chapter 2, sections III and IV). 6. If this is an example of ‘anti-democratic’ policing, it is worth comparing it to similar incidents involving international actors in BiH. Walker (1997) describes Momčilo Krajišnik and his associates from the Serb Democratic Party (SDS) being pelted with stones and eggs when escorted from Hotel Bosna in Banja Luka by British troops. The group took refuge in the hotel after failing to hold a rally supporting one side of the factionally divided Serb representatives from the Eastern and Western RS. In this instance, western states, including the UK, were supportive of Biljana Plavšić who had split from Krajišnik and the Pale-based faction of SDS. There are various ambiguities in this case, including suggestions that 13 Krajišnik’s presence in Banja Luka was linked to an attempted coup, that his party were armed, and that 50 bus-loads of Krajišnik’s supporters had been turned back. Nonetheless, whether an attempt at peaceful assembly or to violently wrest control of RS, even heavily armed external forces either could not, or would not, protect the political actors involved. 7. Electoral regulations in BiH allowed voters to cast their vote in their pre-war municipality. In Prijedor and Foča, this produced results where an electoral alliance of predominantly Bosniak parties received a significant proportion of the vote primarily on the strength of displaced voters. In Prijedor, the alliance gained 35% of the overall vote, but less than 1% of the votes cast in the municipality compared to 92% of those cast from outside. In Foča the comparable figures were 38%, 2%, 93%. 8. Police were observed in 5% of polling stations during 1997 municipal elections, but in all bar 17 polling stations this was justified in accordance with rules and regulations (Schmeets 1998: 86, 173); Kasapović (1997) gives no indication of problems with polling in the previous year’s general elections. 9. For a discussion of the role of representativeness in government agencies, see Selden 1997. With specific reference to criminal justice agencies, see the summary of research in Bradbury and Kellough 2011. 10. Parliamentary elections took place at state and entity level in 1996, 1998, 2000, 2002. For a discussion of shifts in power see [Author 1] 2011: chapter 2.IV. 11. Democratization is a strong current in OHR documentation on Police Restructuring, but co-exist with discourses of effectiveness, which are far more prominent in public broadcasts. See, e.g. the ‘Staklo’ campaign (OHR 2005a). 12. Much of the EU’s influence in BiH is based on a gradual accession process, including a Stabilisation and Association Agreement (Aitchison 2011: 101,178; Juncos 2011). The European Commission also links funding for development projects in BiH to accession criteria (Blaustein, fieldnotes). As the main source of funding for OHR, the EU has access to a further source of influence (OHR 2012). 13. OHR 2005c and 2005d show separate polls highlighting minority support for police reform as part of EU membership and majority support for the existing (Dayton) arrangements. Aitchison (2011:100) gives an account of opposition to the proposals in the RSNA. 14. While Safer Communities illustrates how a global multilateral agency can potentially foster local improvements in democratically responsive policing, the limited availability of core funding within the UN development system means that project managers based at UNDP country offices are often compelled to manage their projects in ways that reflect the perceived interests of potential bilateral donors (Blaustein forthcoming). REFERENCES Aitchison A (2007) Police Reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina: State, Democracy and International Assistance. Policing and Society 17(4): 321-343. ----(2011) Making the Transition: International Intervention, State-Building and Criminal Justice Reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Antwerp: Intersentia. ----(2012) Governing through Crime Internationally? Bosnia and Herzegovina. British Journal of Politics and International Relations (‘Early View’ version). Available from: < http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)1467-856X/earlyview> until print publication. Amnesty International (1998) Concerns in Europe January - June 1998: Bosnia Herzegovina, EUR 01/002/1998, Available from: < http://web.amnesty.org/ai.nsf/Index/EUR010021998?OpenDocument&of=COUNTRIES\BOSNIAHERZEGOVINA>. [Accessed 26 January 2003] ----(2000) Bosnia and Herzegovina – Waiting on the Doorstep: Minority Returns to Eastern Republika Srpska. Available from: < http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/EUR63/007/2000/en/9bc65b80-def3-11dd-b2633d2ffbc55e1f/eur630072000en.pdf>[Accessed 20 April 2012] ----(2001a) Bosnia-Herzegovina: Political violence a severe setback for minority returns, EUR 63/007/2001, Available from: < http://web.amnesty.org/ai.nsf/Index/EUR630072001?OpenDocument&of=COUNTRIES\BOSNIAHERZEGOVINA>. [Accessed 26 January 2003] 14 ----(2001) Bosnia-Herzegovina: Freedom of worship at risk amidst climate of impunity, EUR 63/008/2001, Available from: < http://web.amnesty.org/ai.nsf/Index/EUR630082001?OpenDocument&of=COUNTRIES\BOSNIAHERZEGOVINA>. [Accessed 26 January 2003] Bayley DH (1969) The Police and Political Development in India. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ----(1985) Patterns of Policing: a Comparative International Analysis. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ----(2006) Changing the Guard. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Blaustein J (forthcoming) The Space Between: Negotiating the Contours of Nodal Security Governance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Policing and Society. Accepted for publication July 2012. Bosnia and Herzegovina Ministry of Security (2007) Strategy for Community-Based Policing. Sarajevo. Bowling B and Sheptycki J (2011) Global Policing. London: Sage. Bradbury M and Kellough JE (2011) Representative Bureaucracy: Assessing the Evidence on Active Representation. American Review of Public Administration 41(2): 157-167. Bradley D, Walker N and Wilkie R (1986) Managing the Police: Law, Organisation and Democracy. Brighton: Wheatsheaf. Clarke J, Newman J, Smith N, Vidler E and Westmarland L (2007) Creating Citizen Consumers: Changing Publics and Changing Public Services. London: Sage. Collantes-Celador G and Ionnides I (2011) The Internal-External Security Nexus and EU Police/Rule of Law Missions in the Western Balkans. Conflict, Security and Development 11(4): 415-45. Collier D and Levistky S (1997) Democracy with Adjectives. World Politics 49(3): 430-451. Dawisha K (1997) Democratization and political participation: research concepts and methodologies. In: Dawisha K and Parrott B (eds) Politics, Power and the Struggle for Democracy in South-East Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 40-65. Duffield, M. (2007) Development, Security and Unending War. Cambridge: Polity Press. Durkheim E (1938) The Rules of Sociological Method (8th ed). New York: the Free Press. Elias N (1994) The Civilizing Process: Sociogenetic and Psychogenetic Investigations. Malden MA.: Blackwell. Ellison G and Pino N (2012) Globalization, Police Reform and Development. Doing it the Western Way? London: Palgrave Macmillan. General Framework Agreement for Peace (1995). Available from: <www.ohr.int>. [Accessed 13 August 2012]. Goldsmith A and Dinnen S (2007) Transnational police building: critical lessons from Timor-Leste and Solomon Islands. Third World Quarterly 28(6): 1091-1109. Hinton M (2008) Police and State Reform in Brazil: Bad apple or Rotten Barrel? In: Hinton M and Newburn T (eds) Policing Developing Democracies. Abingdon: Routledge, 213-33. Human Rights Watch (1997) Politics of Revenge: the Misuse of Authority in Bihać, Cazin, and Velika Kladuša. Washington DC. ----(1998) “A Closed, Dark Place”: Past and Present Human Rights Abuses in Foča. Washington DC. Huntington S (1991) The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. Jones T, Newburn T and Smith D (1996) Policing and the Idea of Democracy. British Journal of Criminology 36(2): 182-198. Juncos A (2011) Europeanization by Decree? The Case of Police Reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Journal of Common Market Studies 49(2): 367-389. Kasapović M (1997) 1996 Parliamentary Elections in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Electoral Studies 16(1): 117-21. Kuper A (2004) Democracy beyond Borders: Justice and Representation in Global Institutions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 15 Loader I (2002) Policing, Secritization and Democratization in Europe. Criminal Justice 2(2): 125-53. Loader I and Walker N (2007) Civilizing Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Los Angeles Times (1997) Bosnian Serb Judge Details Beating. Available from: < http://articles.latimes.com/1997/aug/22/news/mn-24826>. [Accessed 20 April 2012] Mackenzie S and Henry A (2009) Community Policing: A Review of the Evidence. Edinburgh: Scottish Government Social Research. Manning PK (2010) Democratic Policing in a Changing World. Boulder, CO: Paradigm. Marenin O (1982) Policing African States: Towards a Critique. Comparative Politics 14(4): 379-396. ----(1998) The Goal of Democracy in International Police Programs. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management 21(1): 159-177. Marks M (2003) Shifting Gears or Slamming the Breaks? A Review of Police Behavioural Change in a Post-Apartheid Police Unit. Policing and Society 13(3): 235-238. McCabe S and Wallington P (1988) The Police, Public Order, and Civil Liberties: Legacies of the Miners’ Strike. London: Routledge. Muehlmann T (2008) Police Restructuring in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Problems of Internationally-Led Security Sector Reform. Journal of Intervention and State Building 1(supplement): 37-65. Office of the High Representative (1997) OHR Chronology January-December 1997. Available from: < http://www.ohr.int/ohr-dept/presso/chronology/default.asp?content_id=5788>. [Accessed 20 April 2012]. ----(2001a) OHR Media Roundup 13 April. Formerly available from: <http://www.ohr.int>. [Accessed 20 May 2005]. ----(2001b) OHR Media Roundup 15 April. Formerly available from: <http://www.ohr.int>. [Accessed 20 May 2005]. ----(2002) OHR Media Roundup 12 July. Formerly available from: <http://www.ohr.int>. [Accessed 20 May 2005]. ----(2004) Decision Establishing the Police Restructuring Commission. Available from: < http://www.ohr.int/decisions/statemattersdec/default.asp?content_id=32888>. [Accessed 4 May 2012]. ----(2005a) Staklo [glass]. Available from: <http://www.ohr.int/ohr-dept/presso/pic/police-campaign/video/tv-clip2-bos.WMV> [Accessed 15 January 2007]. ----(2005b) OHR Media Roundup 9 February. Formerly available from: <http://www.ohr.int>. [Accessed 14 August 2007]. ----(2005c) OHR Media Roundup 23 February. Formerly available from: <http://www.ohr.int>. [Accessed 14 August 2007]. ----(2005d) OHR Media Roundup 29 April. Formerly available from: <http://www.ohr.int>. [Accessed 14 August 2007]. ----(2012) Status, Staff and Funding of the OHR. Available from: < http://www.ohr.int/ ohr-info/geninfo/default.asp?content_id=46241>. [Accessed 17 August 2012]. Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (2008) Guidebook on Democratic Policing. Vienna. Available from <www.osce.org/spmu/23804> [Accessed 18 March 2012]. Parrott B. (1997) Perspectives on Postcommunist Democratization. In: Dawisha K and Parrott B (eds) Politics, Power and the Struggle for Democracy in South-East Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1-39. Pino N and Wiatrowski M (2006) Principles of Democratic Policing. In: Pino N and Wiatrowski M (eds) Democratic Policing in Transitional and Developing Countries. Aldershot: Ashgate, 69-98. Police Restructuring Commission (PRC) (2005) Final Report on the Work of the Police Restructuring Commission of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Available from: <http://www.ohr.int/ohrdept/presso/pressr/doc/prcreport-4feb05.pdf>. Accessed 13 August 2012. Prosecutor v Sikirica. IT-95-8-S (International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991 13 November 2001). 16 Rousseau JJ (1923) The Social Contract. London: Dent. Ryan B (2009) The EU’s Emergent Security-First Agenda: Securing Albania and Montenegro. Security Dialogue 40(3): 311-331. ----(2011) Statebuilding and Police Reform: The Freedom of Security. London: Routledge. Schmeets H (1998) The 1997 Municipal Elections in Bosnia and Herzegovina: an Analysis of the Observations. Dordrecht: OSCE, ODIHR, EC and Kluwer. Selden, S.C. (1997) The Promise of Representative Bureaucracy: Diversity and Responsiveness in A Government Agency. Armonk (NY): M.E. Sharpe. Walker T (1997) British Troops Rescue Karadzić’s Men. The Times, 10 September. 17 Table 1. Democratic policing and responsiveness Jones, Newburn and Manning (2010: 65 ff.) Marenin (1998: 169 ff.) Smith (1996: 190 ff.)* Qualifier 1: Equity Equity (1) Fairness Equality Qualifier 2: Ability to provide minimum General Order Delivery of service (2) Efficiency threshold of security Effectiveness Responsiveness Responsiveness (3) (mechanisms for, or Distribution of power (4) measures of) Competition Information (5) Redress (6) Participation (7) Reaction (to Accessibility complaints) Accountability Accountability Congruence * Jones et al provide a hierarchy of criteria for democratic policing, indicated here by corresponding numbers. The shaded area represents the common ground between policing for democracy and democratically responsive policing. 18