Cases- Crib Sheets

advertisement

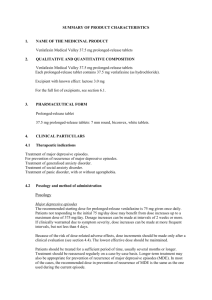

CASE 1: Venlafaxine Overdose Dispensing practice, policy is for dispensers not to open and add drugs to dosette boxes once finalised. Patient taking several medications with dosette box and supervision of adult daughter. Patient under care of hospital psychiatrist seen in clinic and sent with plan for cross tapering of mirtazapine to venlafaxine over 2 weeks. Letter for consultant detailed plan as: Reduce mirtazapine to 30mg daily and start venlafaxine 37.5mg BD for 14 days Venlafaxine 75mg BD thereafter. Prescription from hospital brought to dispensery and read: Venlafaxine 37.5mg BD 28 tablets Venlafaxine 75mg BD 28 tablets Duration of treatment 28 days (No mention of mirtazapine) Medications dispensed as prescribed. Dispensing staff observed daughter opening dosette box and adding both strengths of venlafaxine twice daily. Was approached and following clarification with duty doctor patient given correct regime. Actions taken Letter written by duty doctor to prescribing hospital doctor identifying issues and asking for clearer instruction on prescription given to patient (e.g. venlafxine 37.5mg BD for 14 days THEN venlafaxine 75mg BD to continue) CASE2: Rash decisions Mr M, a 56-year-old developed severe pain in his left foot and made an appointment to see his usual GP, Dr P. Dr P knew him well, having diagnosed Mr M with CKD several years earlier. Dr P suspected he was suffering from gout on this occasion and prescribed diclofenac, with omeprazole cover, since he was also taking aspirin. Less than a month later, Mr M’s symptoms deteriorated and he requested a telephone consultation with his doctor. Dr P arranged for him to have a further prescription issued for diclofenac and omeprazole, and organised blood testing with the nurse to monitor his renal function. His blood tests had confirmed gout, alongside the ongoing CKD. He was commenced on allopurinol, with the advice that he should double the dose of this after ten days of treatment. A fortnight after commencing the new medication (now on 200mg of allopurinol) Mr M started to feel unwell. He reported nausea and an itchy skin on his torso and face. Dr P concluded that the rash was likely to be secondary to a viral illness, and antihistamines were prescribed. That night, the rash seemed to be getting worse, so Mr M consulted with Dr P again the very next day, and a course of prednisolone was commenced. The allopurinol was briefly discussed, and the patient was advised to continue taking it at a dose of 200mg daily. The situation continued to deteriorate and Mr M had two further appointments with Dr P over the course of the next week. His steroids were initially increased, and when this failed to improve symptoms, Dr P suggested the allopurinol should be discontinued. To complicate matters further, Dr P forgot to document the second consultation since he had a busy surgery. Three days later, Mr M developed generalised swelling, throat discomfort and difficulty breathing. Dr P spoke to the patient over the telephone and advised he was likely to be suffering from thrush. Dr P realised at this stage he had failed to document his previous consultations so made some brief notes, without indicating he was doing this retrospectively. The next day Mr M was admitted to hospital by ambulance and diagnosed with StevensJohnson syndrome. He spent a week being treated in ICU with septicaemia and renal failure, but unfortunately died as a result of these conditions. Causation reports concluded that on the balance of probabilities, the patient developed Stevens-Johnson syndrome due to allopurinol, and experts were critical of Dr P’s decision to initiate the treatment after just one attack of gout, and at an increasing dose. Outcome: Experts agreed in this case that Dr P had ample opportunity to make the connection between the rash and the allopurinol, and furthermore, the steroid treatment, which is likely to have contributed towards the ulceration, could have been avoided. The case was indefensible and was settled for a moderate sum. CASE 2: Repeat offender Mrs B was a 49-year-old who, for 18 months, had been increasingly troubled by heavy irregular menstrual bleeding. She was referred to a gynaecologist who carried out a pelvic US and an endomentrial biopsyThe gynaecologist told Mrs B that he would be writing to her GP with his opinion and treatment recommendations for HRT. Mrs B was advised to go and see her GP to get a prescription for HRT in two weeks, allowing time for the clinic letter to reach the GP. In the meantime, the gynaecologist scribbled down the name of the recommended HRT and gave it to Mrs B. Two weeks later, Mrs B took the afternoon off work and went to see Dr M, a locum, at her GP surgery. Unfortunately no clinic letter was available to Dr M on the practice computer notes, Dr M attempted to find out if a paper copy of the letter was available but she had no success. She surprised Dr T by saying that the HRT wasn’t helping her bleeding that had recurred and Dr M was running late and was sensitive to Mrs B’s frustration at having taken time off work for “a waste of time”. Eager to help Mrs B, Dr M looked at the handwritten note the gynaecologist had given her. The writing was barely legible, but Dr M thought the medication looked most like unopposed oestrogen. Mrs B’s blood pressure was satisfactory and it was recorded that Dr M counselled her about risks of breast cancer and thromboembolic disease. Mrs B left with a prescription for unopposed oestrogen. Mrs B continued to be prescribed three-monthly prescriptions of the unopposed oestrogen. The GP who signed the repeat, Dr P, saw from Dr M’s consultation notes that Mrs B had been seen recently by a gynaecologist and the prescription had started as a result of this, and was therefore satisfied it was appropriate. At six months she was seen in surgery by Dr T for a review of her HRT. Dr T did the same recording that a course of unopposed oestrogen was started by the gynaecologist The prescriptions continued for a year, when Mrs B was again called for a HRT review. At this point she surprised Dr T by saying that the HRT wasn’t helping her bleeding that had recurred and which was, in fact, heavier and more persistent than ever. Dr T realised that for many months Mrs B had been mistakenly prescribed an unopposed oestrogen and now had heavy bleeding. Dr T apologised to Mrs B and also explained that she needed to be quickly referred back to the gynaecologist for investigation. She was referred urgently and in view of her history of increasingly heavy bleeding and prolonged exposure to an unopposed oestrogen, a hysteroscopy was carried out. This led to a diagnosis of endometrial cancer. Mrs B had a hysterectomy and made a full recovery. She made a claim against all the doctors involved in her care at the GP practice. The gynaecologist’s original letter was eventually found in the patient’s notes. Outcome: The incorrect prescription could not be defended – Dr M was responsible for her actions. An expert gynaecologist advised that the patient’s subsequent problems were probably a result of this (although there was a low probability that they may have occurred in any case). The practice was liable because there was no system in place to check the prescriptions and uncover Dr M’s mistake. The confusion could have been avoided if the consultant had issued the first prescription. The claim was settled for a moderate sum.