heent - My Illinois State

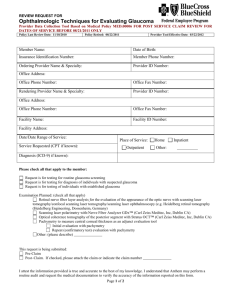

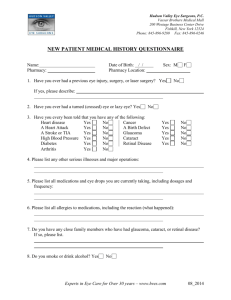

advertisement

1 NUR 475 – FNP III HEENT Normal Vision Changes with Aging: Diagnosis and Management VISUAL CHANGE Decrease in visual acuity Presbyopia FUNCTIONAL CORRELATES Performing all visual tasks Decrease in contrast sensitivity Difficulty seeing under conditions of poor lighter (e.g., night driving, church) and poor contrast (e.g., reading a newspaper) Problems with tunnels, movie theaters, night driving Decrease in dark adaptation Delayed recovery from glare Difficulty with near point tasks Problems with headlights, decreased visual functioning on sunny days MANAGEMENT Increase illumination Increase contrast Corrective eyeglasses Increase illumination Filters Magnification Illumination Sunglasses when outdoors Take a moment to dark/light adapt before trying to walk Sunglasses (but not for night driving) Antireflective lens coating Hats, visors Less fluorescent lighting (Source: Carter, T.L. (September 1994). “Age-related vision changes: A primary care guide. Geriatrics, 49(9), 3745.) Classifications of Visual Impairment CLASSIFICATION Legal blindness Partially sighted Functionally visually impaired DEFINITION Best visual acuity ≤ 20/200 in the better eye or Visual filed ≤ 20o Best visual acuity ≤ 20/70 in the better eye or Visual filed ≤ 30o When activities of daily living are affected Best visual acuity ≤ 20/50 (Source: Carter, T.L. (September 1994). “Age-related vision changes: A primary care guide. Geriatrics, 49(9), 3745. The four most prevalent age-related ocular diseases and the four leading causes of low vision in the US are: Macular degeneration Open-angle glaucoma Cataract Diabetic retinopathy 2 Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) Leading cause of irreversible blindness in people 50 years of age or older in the developed world Prevalence: 30% at age 75+; currently 8 million Americans have AMD Risk factors: advanced age, white race, heredity, systemic hypertension, and a history of smoking Only 10% of individuals with macular degeneration have significant functional visual loss. Since the macula is the area for central vision and provides the highest degree of visual resolution, deterioration of this portion of the retina leads to the loss of central vision. Leads to deficits in form recognition and light sensitivity Types of macular degeneration: o Dry (non-exudative) macular degeneration Most common (80-90% of cases) Manifested by a progressive loss of retinal and pigment epithelium and gradually increasing central blind spot Untreatable o Wet (exudative, or neovascular) macular degeneration Due to accumulation of subretinal blood or exudates (from neovascularization) Can have an acute onset with decreased central vision, metamorphopsia (blurred vision), or a dark spot in the central vision (central scotoma) If found early and not yet in fovea, laser phocoagulation therapy is possible Management (Source: Jager, RD, Mieler, WF, & Miller, JW. (June 12, 2008). NEJM, 358(24), 2606-2617) o Antioxidant supplementation (Preser-Vision, Bausch & Lomb): Vitamins C & E, beta carotene, zinc oxide, and cupric oxide. NOTE: Not recommended for those with any smoking history due to increased risk of lung cancer with beta-carotene supplements in current or former smokers. (Source: Gohel, PS, Mandava, N, Olson, JL, & Durairaj, VK.(April 2008). The American Journal of Medicine, 121(4), 279-281.) o Lifestyle and dietary modifications Quit smoking Decrease dietary intake of fat Maintain healthy weight and BP Increase dietary intake of antioxidants through foods such as green leafy vegetables, whole grains, fish, and nuts o Intravitreal antiangiogenic therapy (injection of antiangiogenic agents directly into the vitreous) Visual rehabilitation for macular degeneration o Self-monitor central vision (Amsler’s chart/Amsler’s grid) o Magnify the area of central vision Hand-held ocular lenses Video enlargement Microfilm reading systems 3 Increase field illumination Glaucoma Definition: Formerly: increased IOP that leads to blindness Now: A group of conditions characterized by eye changes usually associated with increased IOP A progressive optic neuropathy involving characteristic structural damage to the optic nerve and characteristic visual field defects Changes in IOP: Normal IOP: 10-20 mm Hg and IOP difference of less than 3 mm Hg between eyes Pressures of 20-30 mm Hg will cause gradual damage over the years due to atrophy of the retinal ganglion cell layer. o Damage seen on fundoscopy: optic disk shows cupping of the optic nerve head and a decrease in the diameter of the optic vessels as the orange-red area of nerve fiber axons shrinks, the lighter cup in the center grows and the visual field of the patient becomes smaller o Changes in the disk are reflected in the patient’s decreased visual acuity Pressures of 40-50 mm Hg can cause much more rapid vision loss due to ischemia of the optic nerve and retinal structures and may even result in vascular occlusion. For example of how vision can change with glaucoma: http://www.ahaf.org/glaucoma/about/understanding/progression-of-glaucoma.html Incidence: 5 million people worldwide are blind from glaucoma (World Health Organization) o People diagnosed with glaucoma in Third World countries are more likely to progress t blindness due to lack of treatment options In US: 2 million diagnosed with glaucoma High predominance in: o African Americans and Asians than Caucasians o Females more than males o Between ages 55 and 70 4 Conventional pathway for normal flow of aqueous humor: fluid passes from the posterior chamber through the papillary aperture to the anterior chamber, then to the trabecular meshwork, exiting through Schlemm’s canal and finally into the episleral veins, which drain into the venous system via the facial vein. 5 Both diagrams taken from: website of National Glaucoma Research, a program of the American Health Assistance Foundation at http://www.ahaf.org/glaucoma/about/understanding/ 6 Glaucoma Terminology (Erwin, EA & Mendelson, M. (July 2005) Acute presentations of glaucoma. Emergency Medicine, 14-21.) Angle of anterior chamber Primary glaucoma Secondary glaucoma Open-angle glaucoma Acute angle-closure glaucoma Angle created by cornea, iris, and trabecular meshwork Idiopathic increase in IOP Increase in IOP from known disease Insidious increase in IOP that can slowly progress to blindness Medical emergency marked by abrupt increase in IOP that can rapidly progress to optic nerve damage and nerve death A brief note on secondary glaucoma: many secondary causes are rare o exfoliative syndrome and pigment dispersion syndrome debris and granules are caught up in the trabecular meshwork and block the flow of the aqueous humor o lens-induced glaucoma (lens subluxation or dislocation) structures which drain aqueous humor collapse without the lens support o ocular inflammatory disease (can occur with herpes zoster ophthalmicus) o intraocular tumors o ** topical or systemic corticosteroids Open-Angle Glaucoma Most common form of glaucoma Primary type Slow, usually painless process that occurs over a long period of time Diagnosis usually made only after screening of patients in high-risk populations o > 40 years of age o Obese patients o Patients with diabetes, HTN Since flow of aqueous humor is a passive process, increased venous pressure can inhibit the normal removal of aqueous humor. o History of ocular or severe head trauma o Family history of glaucoma Many elderly patients are being treated for open-angle glaucoma and may present with adverse effects from their medications. Treatment: typically topical medications are used (see next page) 7 Class Cap or label color Trade (generic) med names Beta-adrenergic blocking agents Yellow (5%) or light blue (0.25%) Betagan (levobunolol) Timoptic, Betimol (timolol) Betoptic (betaxolol) OptiPranolol (metipranolol) carteolol Local side effects Alpha-adrenergic agents Purple Alphagan (brimonidine) Iopidine (apraclonidine) Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors Orange or white Trusopt (dorzolamide) Azopt (brinzolamide) Redness Itching Edema Prostaglandin F2-alpha analogs Teal Xalatan (latanoprost) Lumigan (bimatoprost) Travatan (travoprost) Miotics Green Isopto Carpine, Pilocar (pilocarpine) Minimal transient ocular discomfort Stinging Burning Irritation Redness Stinging Darkening of the iris Darkening of periorbital skin pigment Longer and thicker eyelashes Blurred vision (especially in younger patients) Tearing Systemic side effects Bradycardia Impotence Fatigue Depression Exacerbation of asthma/COPD Use with caution in patients with heart block, heart failure, asthma, COPD, or depression Dry mouth Fatigue Contraindicated with MAOIs (or within 14 days of MAOI) Minimal transient bitter taste Use with caution in patients with liver disease, severe renal disease, adrenocortical insufficiency, or severe COPD Negligible system side effects Mechanism of action Reduces aqueous humor production Reduce aqueous humor production and increases outflow of aqueous humor Decreases aqueous humor production Increases the outflow of aqueous humor [Note: bimatoprost also marketed as Latisse, for eyelash hypotrichosis] Brow aches Increases the outflow of aqueous humor Compiled from: Erwin, EA & Mendelson, M. (July 2005). Acute presentations of glaucoma. Emergency Medicine, 14-21. and Kowing, D & Kester, E., (July 2007). Keep an eye out for glaucoma. The Nurse Practitioner, 18-23. 8 If medications are not sufficient to reduce the IOP, laser surgery is the usual next step. Depending in the type of procedure, laser surgery may be used for open-angle, angle-closure or neovascular glaucoma. A laser is directed toward the trabecular meshwork, the iris, ciliary body or the retina and is used in various ways to reduce eye pressure. Laser surgery is performed on an outpatient basis in an eye doctor’s office or clinic after the eye has been numbed. There are several types of laser surgeries: Trabeculoplasty is often used to treat open-angle glaucoma. In argon laser trabeculoplasty (ALT), a high-energy laser is aimed at the trabecular meshwork to open areas in these clogged canals. These openings allow fluid to bypass drainage canals and flow out of the eye. In selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) a low-energy laser treats specific cells in the trabecular meshwork. Because it affects only certain cells without causing collateral tissue damage, SLT can potentially be repeated. Laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI) is frequently used to treat angle-closure glaucoma, in which the angle between the iris and the cornea is too small and blocks fluid flow out of the eye. In LPI, a laser creates a small hole in the iris to allow fluid drainage. Cyclophotocoagulation is usually used to treat more aggressive or advanced open-angle glaucoma that has not responded to other therapies. A laser is directed through the sclera or endoscopically at the eye fluid-producing ciliary body. This helps decrease the production of fluid and lower eye pressure. Multiple treatments are often required. Scatter panretinal photocoagulation is a laser procedure that destroys abnormal blood vessels in the retina which are associated with neovascular glaucoma. The most common side effects of laser surgery are temporary eye irritation and blurred vision. There is a small risk of developing cataracts. Currently, laser surgery is the most frequently used procedure to treat glaucoma. It normally lowers eye pressure, but the length of time that pressure remains low depends on many factors, including age of the patient, the type of glaucoma and other medical conditions that may be present. In many cases, continued medication is necessary, but potentially in lower amounts. (Content on laser surgery taken from: http://www.ahaf.org/glaucoma/treatment/common/) Acute Angle-Closure Glaucoma Relatively uncommon cause of glaucoma Ocular emergency In patients prone to acute angle-closure glaucoma, the anterior angle of the eye is narrower than normal, and the conventional route of aqueous humor outflow is more easily blocked by occlusion of the trabecular meshwork by the iris and the cornea. IOP can rise to 80 mm Hg, leading to permanent, rapid optic nerve injury or death Usual chief complaint: headache or eye pain and a significant decrease in visual acuity o Also: nausea, vomiting, red/painful/swollen eye 9 o Systemic effects from vagal nerve stimulation: diffuse abdominal pain, N, V History: patients may recall episodes of eye pain at night or in dark rooms or theaters, during periods of emotional upset, or after receiving an anticholinergic or sympathomimetic medication such as eye drops given prior to an eye exam. o These episodes may have been relieved with sleep or bright lights, since both cause miosis, pulling open the anterior chamber angle and allowing aqueous humor to flow out. Physical exam o Mid-dilated fixed pupil (commonly oval-shaped) o Hazy cornea (can cause patient to see halos around lights) o Tearing o Conjunctival injection (red eye) o Measurement of ocular pressure in both eyes with tonometry Schiotz tonometer Tono-Pen o Fundoscopic exam: glaucomatous cupping (ratio of the yellow optic cup to the darker pigmented optic disk increases), retinal vessel displacement, and splinter or flame hemorrhages o Visual acuity testing Differential diagnosis o Corneal abrasion or lacteration o Conjunctivitis o Iritis o Uveitis o Herpes zoster o Periorbital cellulitis o Retinal artery occlusion o Cavernous sinal thrombosis o Temporal arteritis o Sinusitis o Migraine headache Treatment: o emergent consultation with an ophthalmologist o combination of medications used for open-angle glaucoma o other meds: optic steroids, miotic agents, NSAIDS, hyperosmotic agents o followed by peripheral irdiotomy or iridectomy Patient education: warn patient that the other eye is also at risk for an acute angle-closure glaucoma episode; emphasize seeking immediate care Cataracts An opacity in the normally transparent focusing lens inside the eye that prevents light rays from being focused clearly on the retina o Blue light most distorted; may help to use yellow-tinted filters on corrective lenses One of the most important causes of reversible blindness in elderly persons 10 Estimated that number of Americans with cataracts will increase by approximately 50% in the next 20 years as the population ages 50% of those over age 40 show signs of lens clouding Leading cause of low vision among whites, blacks, and Hispanics Causes: o Aging o Cumulative UV-B light exposure o Intraocular diseases (uveitis, intraocular malignancies, retinitis pigmentosa, retinal detachment) o Trauma o Drugs (topical and systemic steroids, phenothiazines, phospholine iodide eyedrops) o Endocrine/metabolic disorders (diabetes mellitus, hypoparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, galactosemia) o Congenital Treatment: cataract surgery for removal of the cataractous lens and implantation of intraocular lens When to have cataract surgery: typically when decreased vision interferes with the patient’s ability to function in his/her daily living pattern, occupation, lifestyle and desired or required activities. o Surgery is not indicated just because a cataract is present, since it may be mild and well tolerated. o The surgery may be recommended if the cataract is interfering with diagnosis or treatment of other ocular diseases such as diabetic retinopathy or potential intraocular malignancy o Success rate 80-90% o Potential complications: wet macular degeneration (usually had early-stage MD lesions pre-op), posterior capsular opacification (easily correct with laser procedure), retinal detachment Diabetic Retinopathy (Source: Carter, T.L. (September 1994). “Age-related vision changes: A primary care guide. Geriatrics, 49(9), 3745. Symptoms: decreased acuity, contrast sensitivity, color perception, and dark/light adaptation, as well as glare disability and scotomas Key in preventing visual impairment: early diagnosis and treatment o All people with diabetes should have a yearly retinal exam through a dilated pupil Nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy o Clinical manifestations: dilated retinal veins, microaneurysm, intraretinal hemorrhages, hard (lipid) exudates, cotton wool spots (microinfarcts) and macular edema 11 o Patient needs to be monitored for macular edema and proliferative changes every 3-6 months Proliferative diabetic retinopathy o Clinical signs: neovascularization, vascular fibrosis and preretinal as well as vitreous hemorrhages o Managed with laser photocoagulation Vision Loss in Older Persons (> age 65) Associated with depression, social isolation, falls, and medication errors Should be screened every 1-2 years with attention to specific disorders such as diabetic retinopathy, refractive error, cataracts, glaucoma, and age-related macular degeneration Vision-related adverse effects of commonly used medications, such as amiodarone or phosphodiesterase inhibitors, should be considered when evaluating vision problems Prompt recognition and management of sudden vision loss can be vision saving. Aggressive medical management of diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia; encouraging smoking cessation; reducing ultraviolet light exposure; and appropriate response to medication adverse effects can preserve and protect vision. Drugs that are Toxic to the Eyes (from publication of The American Academy of Ophthalmology) Drugs that cause irreversible damage in recommended doses o Corticosteroids (cause cataracts) o Isotretinoin (Accutane) (can cause pseudo-tumor cerebri) o Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) (causes “bull-s eye” pericentral scotoma) o Ethambutol (can cause visual loss) Drugs that cause reversible damage in recommended doses (cause paralysis of accommodation, so that patients cannot focus on near targets) o Antipsychotics o Antihistamines o Tricyclic antidepressants o Antispasmodics o Some centrally-acting drugs for Parkinson’s Disease Drugs that cause damage only above recommended doses or serum levels o Digoxin (with dig toxicity, may have yellowish-orange vision; usually returns to normal with normal serum dig level) o Phenytoin (Dilantin) can have blurred vision o Carbamazepine (Tegretol) can have blurred vision 12 Eye Pain 13 Iritis Most common is anterior, confined to the iris Acute iritis is the more common form seen by primary care providers (vs. chronic) Occurs in young adults Causes: ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome, sarcoidosis, collagen diseases (RA, SLE), TB, syphilis, toxoplasmosis Manifests as ocular pain, redness, photophobia, and blurred Tearing may be present, but neither purulent discharge nor a history of trauma or presence of foreign body is elicited Exam: pupil tends to be small, may be irregular because the iris has adhered to the anterior lens Conjunctiva is hyperemic = ciliary flush Dx: confirmed by presence of inflammatory cells o The cells, due to the primary inflammation, usually float in the anterior chamber (graded on a scale of 0 to 4+) o The inflammatory cells may layer in the anterior chamber o The inflamed vessels allow protein to leak into the aqueous fluid, making the fluid appear translucent when viewed with a slit lamp Treatment: targeted at decreasing inflammation and alleviating pain o Mydriatic agents (such as phenylephrine) to dilate pupil o Cycloplegic agents (such as atropine) to ease pain and photophobia o Corticosteroid drops to suppress the inflammation Floaters and Flashes Posterior Vitreous detachment The vitreous has the consistency of a dilute gel and is attached to the retina and optic nerve head May sometimes see small specks or clouds moving in the field of vision (floaters) o Often seen when looking at a plain background, like a blank wall or blue sky Floaters are tiny clumps of gel or cells inside the vitreous. What is actually seen are the shadows they cast on the retina When people reach middle age, the vitreous gel may start to thicken or shrink, and pull away from the back wall of the eye, causing a posterior vitreous detachment. o More common in people who: Are nearsighted Have undergone cataract operations Have had YAG laser surgery of the eye Have had inflammation inside the eye Concern: if the vitreous detachment causes a retinal tear, since it can lead to a retinal detachment. This needs to be corrected to prevent vision loss. 14 Also: when the vitreous gel rubs or pulls on the retina, the patient may see what looks like flashing lights or lightning streaks. Need ophthalmology to see if: o Even one new floater appears suddenly o Sudden flashes of light 15 Hearing Problems Hearing Loss in Normal Aging • • • • • Extremely common in old age 65% of those aged 85 years report some hearing problem only 16% have a hearing aid or other assistive listening device only 8% actually use their aid or device 10 dB reduction in hearing sensitivity per decade of life after age 60 Presbycusis (“old man’s hearing”) • Decrease in perception of higher frequency tones (consonants are less audible, so words become only vowels) • • Progresses over time, regardless of amplification Decreased ability to focus on a desired sound by internally masking competing sounds (conversation in a restaurant) To assist patient with presbycusis • • • • Amplification eliminate or decrease background nose when direct verbal communication is attempted Use lowest comfortable tone to speak Do not shout at the person Ear Diseases & Hearing Loss Conductive hearing loss • • • AC < BC Can occur in both the external and middle ear Cerumen impaction = most common external ear cause of conductive hearing loss • A frequently overlooked problem in elderly people with hearing impairment Middle ear conductive hearing loss • • • • Most common = otosclerosis Idiopathic stiffening of the bone surrounding the cochlea Amplification of limited help Surgical approaches that improve ossicle mobility have resulted in significant improvement. Sensorineural hearing loss • • • • Both air and bone conduction are decreased, especially toward higher frequencies Gradual: neoplasms of brainstem or CN VIII; long-term exposure to high-intensity noise Sudden: vascular event within inner ear; medication effects Sudden often accompanied by vestibular sx. of vertigo, dizziness, and nystagmus 16 Metabolic causes of hearing impairment can be from toxic medication effects or from endocrine diseases: • • • Thyroid pancreatic adrenal Assessment of Hearing Impairment • • • • • Obtain thorough history Examine external ear canal Remove cerumen impactions Inspect tympanic membrane Assess hearing sensitivity • • Whisper testing Hand-held otoscope /audiometer Read: “Hearing loss is often undiscovered, but screening is easy” at http://www.ccjm.org/content/71/3/225.full.pdf+html Contains Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly Information on hearing aids Read: “Differential diagnosis and treatment of hearing loss” at http://www.aafp.org/afp/2003/0915/p1125.pdf Includes indicators of hearing loss in infants and young children Table on diagnosis of conductive and sensorineural types of hearing loss Tinnitus: The perception of noises in the ear, head, or both without an external acoustic source. Considered a symptom, not a disease Frequently associated with hearing loss Predictors of tinnitus: o High-frequency hearing deficit o Previous loud noise exposure o Age (more common in age 60-69) Thorough history and physical examination are very important. History components: HPI for chief complaint of tinnitus o Location (unilateral or bilateral) o Duration o Character (pulsatile, intermittent, constant) 17 HTN, DM, smoking, hyperlipidemia, and cerebrovascular disease raise suspicion of atherosclerosis carotid artery disease, especially in an older patient presenting with pulsatile tinnitus Pulsatile tinnitus causes: carotid stenosis, arteriovenous fistula or malformations, aneurysms, aberrant carotid artery, intracranial hypertension, high cardiac output (anemia, hyperthyroidism, drug induced), glomus typanicum, vascular tumors (glomus jugular) o Quality (ringing, hissing, roaring) o Associated vertigo or hearing loss o Perceptual characteristics (pitch, loudness) Medical and surgical history o Noise exposure (occupational, recreational) o Head trauma o Medications and ototoxic agents Antibiotics, diuretics, chemotherapeutic agents (including mechlorethamine and vincristine), high doses of aspirin and NSAIDs, quinine, antidepressants o Dental problems (e.g., TMJ) o Exacerbating factors (diet, stress, activity level, smoking, alcohol) o Review of systems o Prior otologic surgery Psychosocial history o Level of annoyance/Impact on quality of life o Sleep disturbance o Depression, stress o Suicidality Compensation o Pursuing compensation, disability, or other legal action related to tinnitus Physical Examination HEENT o Otoscopy o Tuning fork examination (Weber, Rinne testing) o Testing of cranial nurses o Oral cavity examination o Palpation of temporomandibular joint and inspection of dentition o Have patient turn head toward the side of the tinnitus (causes compression of the internal jugular vein) With a venous cause, the tinnitus will decrease in intensity or cease Turning the head in the other direction will cause an opposite effect If the cause is arterial, the maneuver will not have any effect on the tinnitus Full cardiovascular assessment, noting BP, murmurs, dysrhythmias 18 o Note any carotid and/or temporal artery bruits Not to be missed: vestibular schwannoma, Meniere disease, cholesteotoma, glomus jugular tumor, and temporal bone trauma Red Flags that should prompt a referral to ENT specialist: Unilateral tinnitus Pulsatile tinnitus Tinnitus associated with: o Sudden loss of hearing o Pressure or fullness in one or both ears o Dizziness or balance problems o Fluctuating hearing Diagnostics Routine lab testing without a pertinent history is not recommended If indicated testing may include o CBC with diff to R/O anemia or infection o CMP to determine presence of underlying health conditions such as DM o ESR to screen for autoimmune process o FLP to determine possible risk factor for atherosclerosis o Thyroid function tests o Vitamin B12 and folate levels might be considered o Tests for infectious causes such as syphilis, HIV, or Lyme disease may be warranted based on H & P data Tympanometry Audiogram (hearing threshold level > 25 decibels is considered abnormal) NOTE: All patients with unilateral tinnitus or pulsatile tinnitus should be referred to an otolaryngologist for further evaluation and any radiologic testing. If has pulsatile tinnitus and has had recent head trauma or surgery, an urgent referral to an otolaryngologist is warranted. o If specialty services are not available, send to emergency department. Counseling: Stress management Improvement of sleep patterns Avoiding silence by maintaining a safe level of background noise (tapes, white noise generators, radios) Promotion of relaxation and regular exercise Examine diet, avoiding excessive use of caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and salt 19 Engagement in meaningful activities and hobbies Avoid overuse of ASA, NSAIDs, or other potentially ototoxic agents References: Newman, C.W., Sandridge, S.A., Scott, M.N., Cherian, K., Cherian, N., Kahn, K.M., & Kaltenbach, J. (May 2011). Tinnitus: Patients do not have to “just live with it”. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 78(5), 312-320. Ruppert, S.D., & Fay, V.P. (October 2012). Tinnitus evaluation in primary care. The Nurse Practitioner, 37(10), 2026. Cerumen Impaction One of the most common reasons patients seek medical care for ear-related problems Cerumen normally expelled from the ear canal by a self-cleaning mechanism assisted by jaw movement Use of hearing aids or earplugs may cause stimulation of cerumen glands, leading to excessive cerumen production Treatment options o Irrigation o Manual removal o Topical preparations Considerations o Narrow ear canal may limit visualization and increase risk of trauma from irrigation and manual removal common in persons with Down syndrome, other craniofacial disorders, chronic external otitis o Perforated TM: manual removal preferred technique o Persons with diabetes: cerumen pH higher than normal, may facilitate growth of pathogens; consider ear drops to acidify the ear canal after irrigation o Patients with AIDS: tap water irrigation may pose risk for malignant external otitis o Anticoagulant therapy: higher risk of cutaneous hemorrhage or subcutaneous hematoma with instrumentation Reference: Armstrong, C. (November 1, 2009). Diagnosis and management of cerumen impaction. American Family Physician, 80(9), 1011-1013. Allergic rhinitis Affects 10-30% of adults and 40% of children in US Characterized by one or more of following nasal symptoms o Congestion o Rhinorrhea (anterior and posterior) o Sneezing 20 o Itching May affect a patient’s quality of life through fatigue, headache, cognitive impartment, sleep disturbance Types o Seasonal: caused by seasonal allergens o Perennial: caused by dust mites, molds, animal allergens, occupational allergens, pollen Risk factors o Family history of atopy o Serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels > 100 IU/mL before 6 years of age o Higher socioeconomic class o Positive allergy skin prick test Treatment o Step 1: allergen avoidance and patient education o Step 2: For mild intermittent symptoms Second-generation oral or intranasal antihistamine, as needed For mild to moderate persistent symptoms Intranasal corticosteroids alone as 1st line treatment Consider nasal irrigation or decongestants for nasal congestion o NOTE: Patients should be instructed to use only sterile, distilled or previously boiled water for nasal irrigation (To avoid primary amebic meninogencephalitis that occurred in patients who irrigated their sinuses with neti pots and contaminated tap water). Consider ipratropium (Atrovent) or intranasal antihistamines for rhinorrhea Consider oral or intranasal antihistamine for persistent nasal ocular symptoms For severe persistent symptoms Intranasal corticosteroids PLUS oral or intranasal antihistamine, oral leukotriene receptor antagonist, or intranasal cromolyn (Nasalcrom) If symptoms persist, consider immunotherapy referral or alternative treatments (e.g., allergen avoidance, nasal irrigation, acupuncture, probiotics, herbal preparations) Examples of medications o Second-generation oral antihistamines Zyrtec, Xyzal, Claritin, Clarinex, Allegra o Intranasal antihistamines Astelin, Patanase o Intranasal corticosteroids Beconase, Rhinocort, Omnaris, Veramyst, Flonase, Nasonex, Nasacort 21 o o Intranasal anticholinergics Atrovent Leukotriene receptor antagonists Singulair References: Lambert, M. (July 1, 2009). Practice parameters for managing allergic rhinitis. American Family Physician, 80(1), 79-85. Sur, D.K., & Scandale, S. (June 15, 2010). Treatment of allergic rhinitis. American Family Physician, 81(12), 14401446. Common viral infections in older adults: Cold vs. Flu…How do you tell the difference? Fill in the following table based on your readings: Cold Symptoms Onset Fever Headache General aches, Pain Fatigue, Weakness Extreme Exhaustion Stuffy Nose Sneezing Sore Throat Chest Discomfort, Cough Complications Prevention Treatment Flu (Influenza) 22 Dental caries, infections, xerostomia, candidiasis, oral cancer, tongue conditions Read: “Common Oral Conditions in Older Persons” at http://www.aafp.org/afp/2008/1001/p845.pdf Read: “Oral Manifestations of Systemic Disease” at http://www.aafp.org/afp/2010/1201/p1381.pdf Read: “Common Tongue Conditions in Primary Care” at http://www.aafp.org/afp/2010/0301/p627.pdf Hoarseness: Altered voice quality, pitch, loudness, or vocal effort that impairs communication or reduces voice-related quality of life. Causes of Hoarseness Inflammatory or irritant o Allergies and irritants (e.g., alcohol, tobacco) o Direct trauma (intubation o Environmental irritants o Infections (URI, including viral laryngitis) o Inhaled corticosteroids o Laryngopharyngeal reflux o Vocal abuse Neoplastic o Dysplasia o Laryngeal papillomatosis o Squamous cell carcinoma Neuromuscular and psychiatric o Multiple sclerosis o Muscle tension dysphonia o Myasthenia gravis o Nerve injury (vagus or recurrent laryngeal nerve) o Parkinson disease o Psychogenic (including conversion aphonia) o Spasmodic dysphonia (laryngeal dystonia) Associated system diseases o Acromegaly o Amyloidosis o Hypothyroidism o Inflammatory arthritis (cricoarytenoid joint involvement o Sarcoidosis 23 Clues that may suggest a serious underlying cause of hoarseness: Associated with hemoptysis, dysphagia, odynophagia, otalgia, or airway compromise Concomitant discovery of a neck mass History of tobacco or alcohol use Neurologic symptoms Possible aspiration of a foreign body Symptoms do not resolve after surgery (intubation or neck surgery) Symptoms in a neonate Symptoms in a person with an immunocompromising condition Symptoms occur after trauma Unexplained weight loss Worsening symptoms Diagnosis/Treatment When onset of hoarseness is acute, lasting < 2 weeks, with an apparent benign cause (e.g., recent vocal abuse, URI, allergy, GERD), and there is nothing to suggest a more serious etiology, empiric treatment may be instituted with further evaluation In patients with recent symptoms of GERD, may try treating with short courses of high-dose PPIs to see if hoarseness improves If systemic condition known to cause hoarseness (hypothyroidism, Parkinson disease) is present, treat underlying condition. If no improvement in 4 weeks, refer for laryngoscopy When hoarseness lasts longer than 2 weeks and does not have an apparent benign cause, direct evaluation of the larynx by direct or indirect laryngoscopy is indicated CT or MRI should not be performed in patients with primary hoarseness before visualizing the larynx (grade C recommendation)…it is reserved for assessment of specific pathology after the larynx has been visualized. Vocal hygiene o Humidification of the air o Avoidance of smoke, dust, and other inhaled irritants o Avoidance of frequent coughing or throat clearing o Avoidance of shouting or speaking loudly for prolonged periods o Increased fluid intake; avoidance of large meals, excessive caffeine and alcohol use, and spicy foods Referral to speech-language pathologist for voice therapy References: Feierabend, R.H., & Malik, S.N. (August 15, 2009). Hoarseness in adults. American Family Physician, 80(4), 363370. Huntzinger, A. (May 15, 2010). Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hoarseness. American Family Physician, 81(10), 1292-1296. 24 Driving Requirements for driving include: Cognitive capacity, with knowledge of road regulations, how to operate a motor vehicle, and how to arrive at a certain destination Sensory capacity, with visual acuity and hearing ability Motor function, with an intact musculoskeletal system and manual dexterity Neuromuscular capacity, with strength, coordination, and reaction time Skills to integrate the above activities simultaneously in order to drive safely. Read: “How to assess and counsel the older driver” at http://www.ccjm.org/content/69/3/184.full.pdf+html Be aware of state law requirements for license renewal, for example in Illinois: Drivers age 21 through 80 — licenses are valid for four years and expire on a driver's birthday; drivers age 81 through 86 — licenses are valid for two years; drivers age 87 and older must renew their licenses each year. Vision screening is required for all drivers renewing at a facility. All persons age 75 and older must take a driving exam. (http://www.cyberdriveillinois.com/departments/drivers/drivers_license/drlicid.html) Illinois is one of the few states that does not accept reports from concerned citizens on drivers thought to be unsafe. The state only accepts reports from law enforcement officers and physicians. If a state agency finds a complaint reasonable and credible, it may ask the reported driver to submit additional information, which could be used to help determine if a screening or assessment is justified. (http://seniordriving.aaa.com/states/illinois)