MOSCOU SEPT 2012 Advanced Treatment Planning Of Single

advertisement

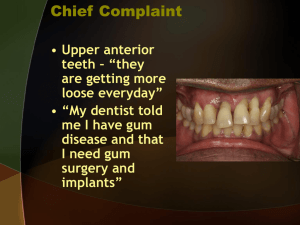

MOSCOU SEPT 2012 Advanced Treatment Planning Of Single Anterior Implants Today, osseointegration is a given, a predictable biological phenomenon with almost all existing implant systems, regardless of their macro and micro designs and surfaces. Nevertheless, novice and experienced clinicians alike are challenged to achieve as a matter of routine the aesthetic integration of a dental implant with the surrounding soft tissues. When considering the “pink esthetic score” (P.E.S) for an objective appraisal of the soft tissue, seven parameters must be taken into account according to Fürhauser et al: Mesial papilla; Distal papilla; Soft tissue level; Soft tissue contour; Soft tissue texture; Soft tissue color; Alveolar process deficiency Visual comparison of the PES for an implant restoration to the PES of adjacent or contralateral teeth generally shows several discrepancies.” The challenge of creating inconspicuous implant-supported restorations is one of the greatest for clinicians and requires one to establish a perfect treatment plan with a biological emphasis in order to maximize the volume of connective tissue and to avoid tissue recession. In the anterior zone, implants are primarily indicated after tooth loss due to trauma, infection, or in healed sites under a pre-existing fixed partial denture. Therefore, the surrounding hard and soft tissues are frequently deficient and unable to mimic the architecture and color of the adjacent gingiva and interdental papillae. Hence, a modern treatment plan should account for these deficiencies, which means that during initial consultation the clinician’s objective is to determine what actions are to be undertaken to obtain to this final result, with durable stability. The gingival biotype is an essential parameter to consider at this stage, since thin and medium biotypes require special care because of frequent unesthetic soft tissue recession, sometimes even with perforation. This is why one must inform the patient, obtain his or her consent, and plan the grafting of biomaterials, autogenous bone, and/or connective tissue prior to or during implant placement in order to thicken hard and/or soft tissues and to provide both stability and esthetics to the surrounding implant mucosa. Implant dentistry is quite different from dentistry performed on natural teeth, since implant restorations are transmucosal and involve the 3D biological space. Peri-implant mucosa is simply adherent to titanium or zirconium oxide surfaces, rather than attached to root surfaces through collagen bundles deeply inserted in the cementum (i.e., Sharpey fibers). Therefore, the mechanical resistance of connective tissue adhesion is low and, when bone support is lacking, peri-implant mucosa easily recedes. In restorative dentistry, every effort is made to be non invasive; in implant dentistry, however, one seldom can. There are only a few clinical situations when one can be conservative and preserve the tissues rather than regenerate them: In extraction sites, for example, when the socket does not show any loss in crestal bone height and width, any recession of soft tissue, and when the biotype is thick. It is to be noted that when this clinical situation exists and the biotype is thin, preserving alone is not sufficient over the long term to provide soft tissue stability. Experience has shown that grafting connective tissue is mandatory in extraction sites with a thin gingival biotype to avoid medium- or long-term recession. A pouch grafting procedure is then preferable to raising a flap, which has a greater negative impact on the blood supply. In other terms, planning anterior implant cases requires one to primarily determine (and stage) the surgical procedures that will allow the peri-implant tissue to be undistinguishable from the adjacent tissue in the long run, and stable--even at the expense of more invasive surgeries. In the second place, decisions have to be made in the choice of implants, abutment design, abutment material, timing to connect the definitive abutment, submergence profile of the provisional restoration, etc, since all factors may impact the final outcome. Prosthetically, the modern trend is to connect final abutments as soon as possible, preferably during implant placement, and leave them undisturbed in order not to disrupt the mucosal barrier with multiple disconnections. Hence, it is recommended every time possible to precisely plan the final position of the implant(s) via a model-guided technique or a computer-guided procedure. A titanium or, better yet, zirconia abutment can be CAD/CAM-fabricated, inserted at time of surgery, and prescanned. With a concave abutment transmucosally, such as in the Nobel Curvy® system, or with a platform switching technique, the connective tissue is thickened and provides better mechanical resistance and stability. This planning clearly requires precision in the diagnostic phase, anticipation in the 3D placement of the implant, and the laboratory prefabrication of abutments and provisional restorations. There is no magical recipe in this treatment, and several options may be clinically successful in different hands. Yet the anatomical placement of the implant must allow the formation of a 3D biological space that will not affect the esthetic outcome; the PES too should be good or excellent. This generally implies the use of zirconium oxide abutments (at least in thin and medium biotypes) and all-ceramic restorations, or one-piece screw-retained zirconia-based ceramic restorations (see clinical example below). At present, modern esthetic implant dentistry must minimize tissue trauma, protect the blood supply, limit the manipulation of prosthetic components, and use biocompatible materials such as titanium and zirconia. Furthermore, it should undercontour the transgingival component and provide immediate esthetic tissue support after one-stage implant placement.