Arriving at a Thesis Reading Strategies

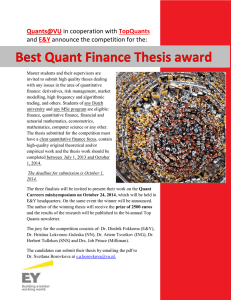

advertisement

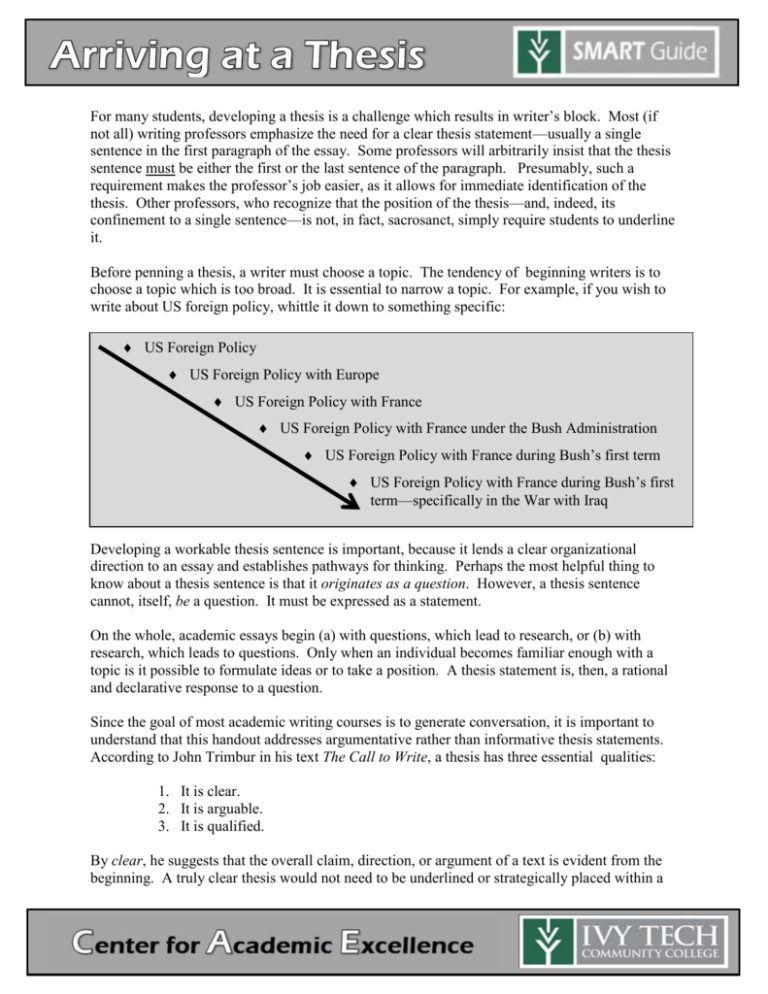

For many students, developing a thesis is a challenge which results in writer’s block. Most (if not all) writing professors emphasize the need for a clear thesis statement—usually a single sentence in the first paragraph of the essay. Some professors will arbitrarily insist that the thesis sentence must be either the first or the last sentence of the paragraph. Presumably, such a requirement makes the professor’s job easier, as it allows for immediate identification of the thesis. Other professors, who recognize that the position of the thesis—and, indeed, its confinement to a single sentence—is not, in fact, sacrosanct, simply require students to underline it. Before penning a thesis, a writer must choose a topic. The tendency of beginning writers is to choose a topic which is too broad. It is essential to narrow a topic. For example, if you wish to write about US foreign policy, whittle it down to something specific: US Foreign Policy US Foreign Policy with Europe US Foreign Policy with France US Foreign Policy with France under the Bush Administration US Foreign Policy with France during Bush’s first term US Foreign Policy with France during Bush’s first term—specifically in the War with Iraq Developing a workable thesis sentence is important, because it lends a clear organizational direction to an essay and establishes pathways for thinking. Perhaps the most helpful thing to know about a thesis sentence is that it originates as a question. However, a thesis sentence cannot, itself, be a question. It must be expressed as a statement. On the whole, academic essays begin (a) with questions, which lead to research, or (b) with research, which leads to questions. Only when an individual becomes familiar enough with a topic is it possible to formulate ideas or to take a position. A thesis statement is, then, a rational and declarative response to a question. Since the goal of most academic writing courses is to generate conversation, it is important to understand that this handout addresses argumentative rather than informative thesis statements. According to John Trimbur in his text The Call to Write, a thesis has three essential qualities: 1. It is clear. 2. It is arguable. 3. It is qualified. By clear, he suggests that the overall claim, direction, or argument of a text is evident from the beginning. A truly clear thesis would not need to be underlined or strategically placed within a particular paragraph. It would, instead, be obvious to the reader. By arguable, Trimbur means that the topic itself should be controversial and generate debate. Of course, a merely informative paper would not need an arguable thesis. By qualified is meant that the thesis should not be overly confident and should avoid taking absolute positions. For example, to say that “Shakespeare’s excessive familiarity with the traditions of the court proves that his works were not his own but were those of a courtier for whom Shakespeare was merely a front man” is much too certain. It would be better to drop the word prove, and to use suggests or implies instead—or to otherwise tone down the claim. There is no place in academic writing for assertions that are doctrinaire or in any way intimidating. A good thesis leaves room for further discussion—its aim is not to shut down but to extend the conversation. Having selected a topic, it is important to educate oneself on the issues, and to become aware of the controversies—or aware of gaps in information, where the discussion is lacking. Only then is a writer able to ask questions and to formulate opinions—and ultimately to generate new knowledge. Thesis statements are of two sorts: (a) Simple statements, and (b) Sign-posted statements. A simple thesis statement is merely a claim: Shakespeare did not write the plays which are attributed to him. Obviously, the statement will require explanation, and will generate a number of paragraphs in support of the claim. A sign-posted statement includes the organizational direction of the essay: Since it is unlikely that William Shakespeare, a humble commoner, could have written so intimately of life at court, it is reasonable to conclude that the real author was a courtier—perhaps Francis Bacon, Edward de Vere, William Stanley, or Christopher Marlowe. Clearly, the above sign-posted thesis predicts the shape which the essay will take: an introduction, followed by four paragraphs (one each for Francis Bacon, Edward de Vere, William Stanley, and Christopher Marlowe) and a conclusion. Naturally, such a thesis simplifies the writing of the essay and is well worth the time required for its construction. Challenging though writing a good thesis statement may be, making the time and effort will certainly pay dividends. Choose an interesting topic; narrow it down; spend time informing yourself about the issues; formulate questions which require further investigation; and then spend time developing a qualified but workable thesis, whether simple or sign-posted. It will provide the scaffolding for your essay, give purpose to your thinking and research, and in the end streamline the writing process to a degree which you may find pleasantly surprising.