THE HUGUENOTS OF FRANCE 2

advertisement

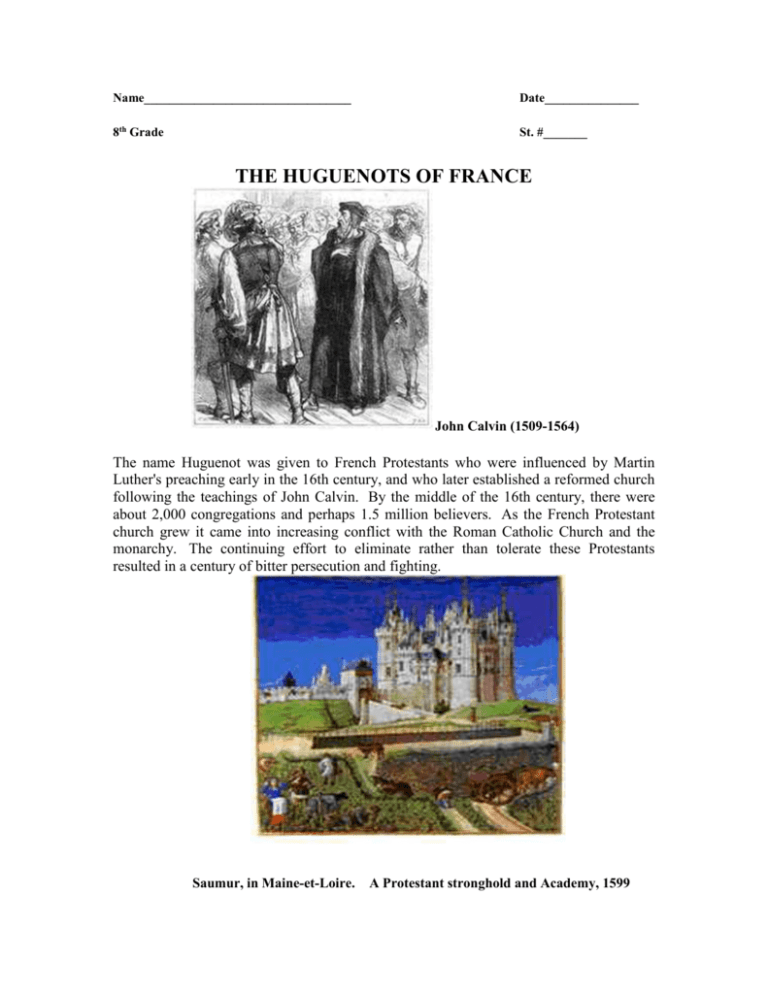

Name_________________________________ Date_______________ 8th Grade St. #_______ THE HUGUENOTS OF FRANCE John Calvin (1509-1564) The name Huguenot was given to French Protestants who were influenced by Martin Luther's preaching early in the 16th century, and who later established a reformed church following the teachings of John Calvin. By the middle of the 16th century, there were about 2,000 congregations and perhaps 1.5 million believers. As the French Protestant church grew it came into increasing conflict with the Roman Catholic Church and the monarchy. The continuing effort to eliminate rather than tolerate these Protestants resulted in a century of bitter persecution and fighting. Saumur, in Maine-et-Loire. A Protestant stronghold and Academy, 1599 These French Protestants were inspired by the German monk Martin Luther and then generally followed the teachings of John Calvin, a French theologian who preached in Geneva from 1537 to 1564. The Reformed Church was established in France by the mid1530s. The new religion rejected the excesses and doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church and the French monarchy. Protestant theologians such as Calvin taught that a universal priesthood of believers could find salvation, not through the interventions of a church, but through individual faith alone. The Bible was translated for the first time into the vernacular languages and the new faith was based on the study and individual interpretation of the Bible. From the 1530s to 1560, the French Reformed Church experienced rapid growth, particularly among the nobility. By the 1560s, the Huguenots had their own churches, schools, garrisoned towns, manned castles and fortifications. But as the Protestant Church grew, conflict with the Roman Catholic Church and the Crown intensified. As early as the 1530s, the first religious refugees began to leave France. In 1561 Catherine de Medici, as Regent to her minor son Charles IX, granted certain privileges to the Protestants, but the peace was short-lived. In March of the following year a group led by François, Duc de Guise, a staunch Catholic, attacked a congregation of unarmed Huguenots who were worshipping in a barn at Vassy, killing over one hundred people. This began the Wars of Religion, which tore France apart for thirty-five years until relative peace was established following the Edict of Nantes in 1598. In 1570 Catherine de Medici declared the Peace of St. Germain, primarily to keep the Protestants from taking Paris. By that time Gaspard de Coligny, Admiral of the French Navy and Governor of Picardy, had become a leader and spokesman for the Protestant cause. In August 1572, Prince Henri de Navarre, a Protestant, was to marry Marguerite de Valois, sister of Charles IX, in Paris. The Roman Catholic leaders, together with the Regent, thought that this was an opportunity to assassinate Coligny and many of the Protestants who would be in Paris for the wedding. During the night of August 23, 1572, those plans were carried out. The young King Charles IX was there with his mother and brother Henri d’Anjou (later Henri III). After he had been pressed to agree to the plan he was reputed to have ordered “the death of all the Protestants of France, so that none would remain to reproach him later.” Coligny was murdered and the frenzy spread through Paris and throughout the provinces, resulting in the deaths of an estimated three thousand men, women, and children in three days. This was the infamous St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. Following the death of Charles IX in 1574 and the murder of his brother Henri III in 1589, Henri de Navarre was crowned King Henri IV. Although Henri IV had converted to Catholicism for political reasons, he established basic rights for the Protestants. When Henri IV was assassinated in 1610, the Protestants lost much of their protection. The rise of the absolute monarchy began with his son and successor, Louis XIII, who regarded the Protestants as a threat to the monarchy. His regent, Cardinal Richelieu, was obsessed with eliminating all Huguenot communities in France. Protestant freedoms were restricted and, in 1622 the Crown began the first of three Huguenot Wars that ended in 1627 with the siege and fall of La Rochelle and an uneasy peace. The Edict of Nantes Louis XIV, who had ascended the throne as a young boy in 1643, believed that there should be “one king, one law and one religion” for France. By 1665, Huguenot churches and schools began to be abolished and more restrictions were gradually imposed. Huguenot men and women were imprisoned and their children kidnapped or forcibly removed and sent to orphanages and convents to be raised in the Roman Catholic faith. The families of these children were billed for their room and board. Between 1681 and 1686 royal troops were forcibly quartered with Huguenot families in several provinces in order to compel them to renounce their faith; these “dragonnades” were carried out in several provinces where Protestants were numerous. The Huguenots were expected to pay the soldiers’ board and the “booted missionaries” punished those who resisted. Those who did not agree to become Roman Catholics and who could not flee the country were often imprisoned, tortured or put to death. By 1685, Louis XIV believed that years of intimidation and persecution had largely done away with the Huguenots, and the Edict of Nantes was revoked. The Revocation led to the destruction of the last Protestant churches in France and forbade any assembly of nonCatholics. Protestant ministers were given fifteen days to leave France or face execution. The property of those who had already fled was forfeited to the Crown. Protestant men and women caught attempting to leave France were condemned to galleys or imprisoned. The remnants of the Protestant church in France went underground, holding secret worship and becoming known as the Church of the Desert, or le Désert. They worshipped in private homes, in deep woods and in caves – wherever they could gather together. Those who were caught attending these secret worship services were relentlessly punished; men were sent to the galleys and women to convents where they were forcibly converted. Prior to the Revocation, there were about eight hundred thousand Huguenots in France. In the face of horrible persecution, approximately five hundred and fifty thousand of them recanted their faith. During the next twenty years, it is estimated that about a quarter of a million Huguenots left France. Many fled to friendly neighboring countries such as Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands and parts of Belgium. Others escaped to England and Ireland from where they embarked for the West Indies and British North America, especially to the Carolinas, Virginia, New York and New England. Some eventually migrated as far as South Africa. The Huguenot refugees who left France were generally merchants, artisans, craftsmen, weavers or were skilled in specific trades. Many were well-educated, and some were able to establish new roles as entrepreneurs or professionals where they settled. They were generally well-received where they located, and became industrious members of their new communities. Some of these immigrants and their descendents played significant roles in the history of their newly adopted countries. The Huguenot Society of South Carolina was founded in 1885 by their descendants in order to honor and perpetuate the memory of these French Protestant men, women and children. Suggested Reading Baird, Charles W., D.D., History of the Huguenot Emigration to America; 2 vols., 1885. Reprint (2 vols. in 1), Baltimore: Regional Publishing Co., 1966. Reissued Baltimore, Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1991. Still a valuable resource. Butler, Jon, The Huguenots in America, A Refugee People in New World Society; Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1983. Currier-Briggs, Noel, and Royston Gambier, Huguenot Ancestry; Phillimore, 1985. Gwynn, Robin D., Huguenot Heritage, The History and Contributions of the Huguenots in Britain; 2nd Revised Edition with enlarged plate section, Brighton, Sussex Academic Press, 2001. Gwynn, Robin D., The Huguenots of London; United Kingdom, Sussex Academic Press, 1998. Museum of London and the Huguenot Society of London, The Quiet Conquest: The Huguenots, 16851985; London, Museum of London, 1985. A “coffee table book” with many wonderful pictures. Van Ruymbeke, Bertrand, and Sparks, Randy J., editors, Memory and Identity: The Huguenots in France and the Atlantic Diaspora; Columbia, South Carolina, University of South Carolina Press, 2003. Van Ruymbeke, Bertrand, From New Babylon to Eden: The Huguenots and Their Migration to Colonial South Carolina; Columbia, SC, University of South Carolina Press, 2006. These books are all available for research at the Huguenot Society Library, 138 Logan Street, Charleston. We also have a number of books on Huguenot settlements in America, on local history and Huguenot subjects for sale in our offices on Logan Street. The Charleston County Public Library also has most of the books listed here, as well as an extensive collection of South Carolina reference books.