An Empirical Test of the Residual View

advertisement

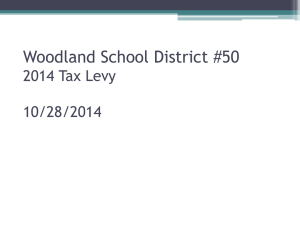

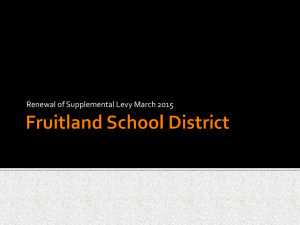

Fiscal Illusion from Property Reassessment? An Empirical Test of the Residual View Justin M. Ross Assistant Professor School of Public & Environmental Affairs Affiliated Faculty Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis Indiana University Bloomington, IN 47405 (812) 856-7559 justross@indiana.edu Wenli Yan Assistant Professor School of Public & Environmental Affairs Indiana University Bloomington, IN 47405 (812) 855-1978 mushbb@gmail.com Abstract The textbook view of the real property tax is that the tax rate is simply a residual, determined by dividing the revenue to be raised from the property tax by the taxable base of assessed values. As such, tax rate adjustment is automatic and changes in assessed values are neutral with respect to property tax revenue. Critics often claim that policymakers do not fully reduce the tax rate in response to increasing assessed values, allowing them to effectively raise revenue without raising tax rates. Using data from Virginia cities and counties between 2000 and 2008, this paper estimates the response of levy growth rates to property reassessment by taking advantage of a policy environment that offers a natural experiment in the execution of mass reappraisals. A timing lag in the implementation of updated property assessments to be used in setting the tax rate further allows the study to disentangle assessed value growth from other forms of economic growth, including the market values of property. Our findings provide partial support for the fiscal illusion critique, as mass reappraisals per se provide cover for politicians to raise levy growth rates; however, overall the growth in aggregate taxable assessed values is largely irrelevant. Keywords: Property assessment, property tax rates, fiscal illusion, median voter theory JEL Classification: H71, H73, H83 * We appreciate the assistance of graduate assistant Larry Summers for assistance in collecting data from Virginia county governments. We also appreciate helpful comments and feedback from John Mikesell, Bradley Heim, Denvil Duncan, Ed Gerrish, Ryan Woolsey, George Zodrow, Bill Gentry, and two anonymous referees. Any errors are solely those of the authors. 1. INTRODUCTION The administration of the real property tax makes it unlike any other ad valorem tax in the United States. Since most individual property parcels are seldom traded, an assessment process is required to estimate their fair market value.1 The assessment of the property can be of significant importance to individual property owners for determining their tax liability, but in the aggregate the process is considered by budget analysts to be irrelevant to the revenues raised (the “residual view”).2 In the United States, local governments formally determine the property tax levy, which is the aggregate amount of revenue to be raised from the taxation of property to meet the predetermined aggregate demands of public expenditures (Ladd, 1991; Mikesell, 2011). The millage rate is then a matter of arithmetic as it is the result of dividing the levy by the total assessed values in the jurisdiction. If all properties experienced a uniform 10% increase in their assessed values, then the millage rate would be revised down so that the tax bill would be unchanged across all taxpayers in meeting the original levy. The formal role of the property reassessment is to maintain equity by keeping assessed values in line with their true market value. In fact, this is exactly the way in which textbooks in public financial management and budgeting explain the setting of the property tax rate (Lee et al., 2008; Mikesell, 2011). Still, the taxpayer’s individual property tax bill is determined by applying the millage rate to their individual assessment, hence the widespread perception that local governments set rates instead of levies. As explained in Fisher’s textbook on state and local public finance (2007, p. 323): In other words, a general rise in property values allows local governments to increase property tax collections without increasing tax rates. Not surprisingly, some individuals are led to conclude that the assessment increase caused the tax increase. This view is not correct because each local government with property tax authority controls and selects, either explicitly or implicitly, the amount of property tax revenue to levy. “Real property” refers to land and its accompanying capital improvements. This is distinguished in tax law from personal property, which can include vehicles or financial assets. 2 The term “residual view” is adopted here from Netzer (1964, p. 207): “…the nominal rate of the tax is essentially a residual, derived by determining the level of expenditures, subtracting state aid and other non-property tax revenues from budget outlays, and comparing the remainder with assessed values…[A]ssessed values are no more ‘actual’ as determinants of property tax yield than are a number of other factors.” 1 1 The popular criticism of the residual view, frequently raised by legislators, journalists, and citizens is that local government officials take advantage of an increase in the property assessments by only partially offsetting the millage rate, so as to increase total real property tax revenue. Since property owners have their individual liability partly determined by the millage rate, local government officials can increase the levy, and raise more revenue while lowering the tax rate and thus claiming they “cut taxes.” In doing so, these critics are arguing that the property tax reassessment process is a source of fiscal illusion that causes the levy to inflate from what would be preferred by the voters. Fiscal illusion has been a subject of substantial interest to public finance scholars, and it is thought to exist in a variety of forms (Dollery and Worthington, 1996). Some forms of fiscal illusion relate to the structure of the tax code, where indirect, hidden, or less salient taxes cause voters to believe that the cost of public services is less than what they perceive it to be. Generally, the property tax is thought of as a fairly salient and visible tax (Cabral and Hoxby, 2010). Renter illusion, however, is thought to arise if renters do not expect these taxes to be shifted into higher rents from the landlord and consequently vote for higher levels of public expenditures (Bergstrom and Goodman, 1973; BlomHansen, 2005). Another form of fiscal illusion, popularly known as the flypaper effect (Oates, 1979; Dougan and Kenyon, 1988), occurs when categorical lump-sum grants are used to expand the public budget by an amount greater than an equivalent increase in voter income from other sources, typically thought to occur when politicians use the grant to feign a lower marginal cost of taxation. The fiscal illusion most related to property reassessment comes from the revenue-elasticity hypothesis that increases in any tax base are automatically directed into new expenditures. As Oates (1975) observed, evidence for the revenue elasticity hypothesis is usually confounded by the fact that revising income or sales tax rates is costly, so an absence of rate revision in response to tax base growth is not necessarily a dismissal of voter preferences. This cannot be the case for property taxes, however, because local governments annually determining their expenditures are, by definition, nominally setting the tax rate, so there are no additional costs from rate adjustment. 2 This revenue-elasticity fiscal illusion critique of the residual view seems to have been partially influential to the passage of Proposition 13 in California (Mikesell, 1980; Martin, 2008), as well as the recent property tax revolt in Indiana when changes in assessment standards caused the taxable value of certain properties to rise significantly.3 Contrary to the residual view, national comparisons of growth in housing prices to property tax revenues have historically been highly correlated, as demonstrated in Figure 1. The popular Mikesell (2011) textbook on public financial administration pays homage to this critique in describing the administration of the property tax rate [p.494]: A government may, of course, see the computed rate, worry about the consequences, and revise the amount of levy it chooses to raise. Empirical evidence to support or refute the residual view, however, has been sparse. This is in part because policy makers may make “legitimate” changes in the levy to accommodate new growth in demand for public services, which often occur with growth in assessed values. Areas which experience the largest increases in property assessments might simply be high growth areas, or voters may demand more public services due to the wealth effects accompanying appreciation in the value of their homes. The purpose of this paper is to provide a direct test of the residual view, a view that would be rejected if it can be shown that assessed value growth causes increases in the property tax levy. This is done by drawing upon data from Virginia cities and counties between 2000 and 2008, where an institutional arrangement reasonably approximates a natural experiment for testing the residual view. In 1984, the state mandated that these areas adopt a fixed reassessment frequency cycle that determines the number of years between reassessments, which has the consequence of causing the timing of contemporary assessments to mimic a random assignment process by making them independent of the economic conditions of the local governments. Data from annual assessment-to-sale price ratio studies allow us to further differentiate between changes in fair market value and assessed values, which differ 3 Mikesell (1980) describes the popular view that increases in assessments caused higher spending from activistpoliticians like Howard Jarvis which lead to their successful push for California’s proposition 13, passed in 1978. More recently, in 2010 Indiana voters passed a constitutional amendment, which is widely seen as a consequence of voter unrest resulting from a change in assessment on the basis of cost of replacement to current fair market values (see Faulk, 2004). 3 because of assessment errors and time lags between mass reappraisals. The identification approach allows us to separate the accumulated demand effects related to economic growth from the potential role of reassessment as a source of fiscal illusion. Our findings are able to detect some amount of fiscal illusion, where increases in assessed values and mass reappraisals cause higher levies. This paper is structured as follows: in the next section, we provide a summary of the previous literature, followed by a section providing the necessary background to understand Virginia as a natural experiment for testing the residual view. The fourth section discusses the model and research methodology, and results are presented in the fifth section of the paper. The paper concludes with a summary of the findings and a discussion of policy implications. 2. PREVIOUS LITERATURE To the best of our knowledge, there are just four papers – Mikesell (1978, 1980), Bloom and Ladd (1982), and Ladd (1991) – whose purpose is to test the residual view. The general difficulty with the existing literature on the residual view is that assessment growth could be correlated with broader economic growth, particularly if there is a marginal propensity to consume public services out of property appreciation that is distinct from other forms of economic growth. Bloom and Ladd (1982) studied changes in property tax levy growth in 241 Massachusetts towns and cities between 1960 and 1978. After controlling for area and year fixed effects, the results suggested that the enactments of mass reappraisals were accompanied by statistically significant 3.5 percent increase in the levy growth rate for cities, but no effect was found in towns. However, the regressions had no other control variables, raising the possibility of omitted variable bias, and the mass appraisals were performed at the discretion of the municipalities, perhaps resulting in an endogeneity bias. Ladd (1991) replicated the specification from Bloom and Ladd (1982), this time using data from North Carolina over 1960-1984, where she argued the state mandates of reappraisal frequency set in earlier years allowed for a more exogenous reappraisal process than was observed in the earlier study of Massachusetts. The 4 findings from North Carolina in Ladd (1991) indicated that mass reappraisals were correlated with increased property tax levy growth of 3 to 8 percent. However, while there were no other annual control variables, just year and area fixed effects, the results were reestimated after splitting the sample by high versus low income and population growth. The evidence from these specifications becomes somewhat more mixed, suggesting these could be potentially important omitted variables. In fact, both Bloom and Ladd (1982) and Ladd (1991) framed their model as a median voter public service demand function, in which case population and income would play a strong theoretical role. The earliest test of the residual view came from Mikesell (1978), who estimated a time-series regression of total property tax levies in the state of Indiana between 1950 and 1972 on state personal income, household personal property, and a dummy variable indicating the presence of a mass reappraisal. The mass reappraisal dummy was associated with a 0.01 percent increase in property tax levies, a magnitude which is neither substantively nor statistically significant. While this finding is consistent with rate adjustment, it must be qualified by the observation that it was local governments rather than the state who determined levies and assessments, and so the state-level time-series approach suffered from aggregation bias. In a 1980 paper, Mikesell again studied the residual view, this time with counties and independent cities in Virginia from 1973 to 1975. Mikesell (1980) finds reassessments to have had an effect on the nominal rate consistent with rate revisions that offset changes in assessed values, but not on the effective tax rate. 4 This provided some evidence that Virginia counties were not completely offsetting the change in property assessed values with tax rate adjustments, but measurement of base growth using the assessment-to-sales price ratio did not allow for a clear inference on how large or small the effect could have been. 4 This is a true limitation in drawing inferences on the residual view for any paper with property tax rate as the dependent variable. For example, Cornia and Walters (2006) present a regression explaining effective property tax rates in five Utah MSAs over 20 years with changes in assessed values, though their interest is in the impact of full disclosure policies rather than the residual view. While they find a negative relationship, consistent with rate adjustments, it is not possible to determine if the rate revisions were sufficient to remain levy-neutral. 5 Beyond papers directly interested in the residual view, related research on the relationship between housing prices and property tax revenues can be informative in terms of testing the hypothesis. One of the more recent examples is presented in Lutz (2008), the main result of which estimates property tax revenue growth among local governments located in Metropolitan Statistical Areas between 1985 and 2005 as a function of multiple lags in the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s (FHFA) housing price index.5 The regression results reveal that the property tax revenue elasticity with respect housing prices is greater than zero, but less than one, causing the author to conclude that property tax rates must partially decline in response to changing housing prices. Interestingly, Lutz (2008, p. 566) also suggests that this result is partially explained as an institutional consequence of unchanging property assessments: Institutional features of the property tax, such as delays in bringing assessed values into line with market values and caps and limitations on the tax, likely explain the lag between house price and tax revenues (and may also influence the magnitude of the relationship). In essence, Lutz’s proposed interpretation seems to be one where increases in assessed values do cause property levy increases and rate changes are caused by voter demand, which would be somewhere between the residual view taught in textbooks and the opposing view of its critics. The paper provides a useful point estimate on the general elasticity of housing prices to property tax increases, but it also highlights why research explaining property tax levies with only fair market value growth do not provide direct evidence on the residual view.6 Other papers (e.g. Alm et al., 2011; Doerner & Ihlanfeldt, 2011; Lutz et al. 2011) which investigate property tax revenues and house prices have this same qualification when it comes to implications for the residual view: without assessed values being part of the regression, it is not possible to differentiate between voter demand shocks and policy makers taking advantage of fiscal illusion in revising the rate. 5 At the time of the Lutz (2008) paper, the housing price index was published by the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight. 6 Furthermore, since the housing price index is quality-adjusted it need not be the case that the assessed values constituting the property base changed in the same manner. Increases in the taxable property base for any reason should permit the form of fiscal illusion required to reject the residual view. 6 In summary, the previous literature directly interested in the residual view has produced mixed results, and may suffer from omitted variable bias. Specifically, what remains to be contributed is an approach where change in assessed values is not contaminated by other growth variables. The next section provides the institutional background on Virginia’s administration of property taxes and real property assessments as the basis for this study. 3. BACKGROUND ON VIRGINIA AS A NATURAL EXPERIMENT Detractors of the residual view are functionally claiming that changes in the assessed values cause changes in the property tax levy through a form of revenue-elasticity fiscal illusion among the voters. Since the most significant changes in assessed values result from mass reappraisals, the ideal natural experimental setting for testing the effect of property reassessments would be to observe a set of local governments whose true property value growth could be observed by the researcher, but have property reappraisals determined by random assignment. As a result, the property reassessment process would be exogenous to the determination of the levy. Furthermore, to be a viable application of the median voter demand model, the policy makers of these governments would have no external constraints imposed by the state in setting their budget with respect to their ability to levy from the property tax.7 As previously described, changes in the property assessments might reflect underlying economic growth effects, which could confound an empirical investigation in the determination of the levy. In most instances, however, assessment values are usually the only widely available data on underlying property growth. It is also conceivable in some instances the property assessments are conducted in some endogenous manner, particularly if there is no cyclical basis for reappraisals. This would be particularly problematic if updates in the property tax rolls coincided with planned changes in property tax levies, perhaps to assure local voters of a more equitable expansion of the tax base or take advantage of fiscal illusion. Furthermore, some states have statutory limitations on property taxes which create a different set 7 Some states set limits on growth rates on property levies, while others limit the growth in taxable property values. 7 of incentives. Local governments may be constrained, for instance, in the amount of revenue growth from one year to the next (e.g. California) or with caps on the property tax liability as a share of assessed values (e.g. Indiana). These types of constraints might induce governments to behave strategically to accommodate median voter demand, both in terms of setting the levy and/or in terms of setting the assessment level. Virginia is home to 134 counties and independent cities, generically referred to here as “counties,” where the institutional conditions reasonably approximate the natural experimental setting.8 First, the state imposes no serious limitation on policy makers in taxing property. The only requirement they face is that notice must be given in a local newspaper if the property tax levy is to grow more than one percent from the previous year. The Virginia Department of Taxation also conducts an annual “sale price ratio study,” in which fair market transactions are randomly sampled across the state, and consequently each property’s selling price is compared to the assessed value at the time of the sale. The median ratio of assessed value-to-sale price (sales ratio) and other common measures are computed and used to evaluate the accuracy of property assessments in each county. These sales ratio studies are published annually, but with an approximate lag of 2-3 years after the sales actually take place, and therefore 1-2 years after the budgeting process. These annual estimates of fair market value growth can be used to capture the amount of growth that might induce demand for more public services. Property tax levies in Virginia are determined by a county council of elected representatives, usually going by the title “Board of Supervisors.” This council varies in number according to the county, and council members are typically staggered so that different members are up for election in different years. The county is the primary level of general purpose local government, and it takes on most local public services such as health, welfare, and education.9 There does exist varying numbers of special governments within the counties which may be delegated differing responsibilities (library, fire, etc.) and 8 In Virginia, there are several independent cities which have the same status as counties in terms of administrative powers and responsibilities. This means they have their own independent general purpose budget. 9 Public school districts are operated at the county level in Virginia. 8 coordinate with the county, usually by proposing their own budget to the council for approval. The property assessment process is also undertaken at the county level, but under the auspices of the county Commissioner of Revenue, another elected official. The local Commissioner of Revenue will either maintain the property tax rolls directly, or appoint a distinct property assessor office whose department maintains the responsibility. Thus, in Virginia, the elected body responsible for determining the tax burden is distinct from the one which determines the property assessments. Virginia is a strong Dillon Rule state, so by and large the public service responsibilities are relatively homogeneously delegated across county governments.10 In addition to making this a reasonably comparable group of governments, this also establishes a useful scenario for the remaining critical aspect of a natural experiment in terms of the timing of mass reappraisals across counties. In 1984, the Virginia Tax Code required that all county governments adopt a frequency cycle for property reassessment.11 Historically, many Virginia counties would go long stretches of time between reappraisals, over 10 years in some cases (Mikesell, 1980). The law stipulates that, for all properties, the frequency of reassessment be greater for the higher population counties than for those with lower populations. Independent cities with populations above 30,000 are required to reassess biannually, while those below the cut-off may choose to reassess either annually or every four years. Counties must reassess every four years, but they can elect a fixed 1, 2, 5, or 6-year cycle if their population is below 50,000. Counties do have the ability to change their assessment cycle frequency, but this is rarely the case and is largely driven by compliance with the state laws as their population grows or shrinks.12 The difference in frequency of reassessment cycles results in the contemporary situation where every year has a different set of counties conducting mass reappraisals. Between 2000 and 2008, there were no two years in Virginia with exactly the same set of counties conducting mass property reassessments. As a “Dillon’s Rule” is the legal precedent that local governments only have the powers and authorities that have been explicitly granted to them by the state. 11 Discussion of the virtues and trade-offs of options in setting reassessment cycles can be found in Mikesell (1980) and Stine (2010). 12 The only example we have found of the changing reassessment frequency in the time frame of our data occurred from 2000 to 2001 as the independent city of Clifton Forge lost its status as county equivalent, and was merged with the encompassing Alleghany County and effectively increasing its population. 10 9 result, the specific year in which a county reappraises property is exogenous to the determination of the property levy, and therefore is probably as close to random assignment as can be hoped for in the natural world. It would seem unlikely that counties determining their assessment frequency cycle in 1984 would do so for the explicit purpose of having a property reassessment take place in a particular year during the millennium decade to hide a tax levy increase. Virginia’s reassessment cycles and sales ratio studies also play an important role in distinguishing between growth in fair market values and assessed values, since in principle the two should be relatively collinear. However, multiyear lags between mass reappraisals create a situation where the year-over-year change in assessed value growth will reflect cumulative changes in fair market values rather than just the single year growth. Furthermore, the accuracy of the assessment process, as measured by Virginia’s previously described sales ratio studies, is not universal across counties. Typically, a county which conducts a mass reappraisal will have a median sales ratio indicating that parcels have an assessment which is 90 to 110 percent of estimated fair market value. In order to identify the possible role of property reassessment in concealing levy growth, there is another important institutional detail in the timing between when the change in assessed value is known to the owners and when it is used in setting the rate. Most property reassessments are conducted within the first three months of the calendar year, with the latest being conducted in June, and the balance of the year is employed for giving notice to the residents and the opportunity to appeal. The budget is set prior to the end of the fiscal year, and as a consequence, the property reassessments are not reflected in the new millage rate until the next calendar year. As an example, even if the reappraisals were conducted in calendar year 2005, it would not be reflected in the millage rate confronting the taxpayer until the next year when the budget was being set for Fiscal Year 2006-2007. This institutional setting allows us to model demand for public services as being a function of contemporaneous market value appreciation, and the lagged period where the intermittently-updated assessed values are finally adopted into the property tax rate as representing the opportunity for policy makers to take advantage of any fiscal illusion. 10 A preliminary look at data from Virginia also reveals why critics may feel the principle of the residual view is not being met. Figure 2 compares the average real property tax levy against the average property tax millage rate between 1999 and 2009. As Figure 2 reveals, on average property tax rates have remained relatively constant, even fallen slightly, while the average revenue raised from real property taxation has more than doubled over the same period. For the pattern in Figure 2 to hold, it had to be the case that growth in assessed values kept pace with the levy so as to remain rate neutral, and Figure 3 confirms this to be the case. These averages, of course, mask a considerable amount of underlying heterogeneity in the conditions experienced across counties, but one can observe why critics of the residual view might be concerned that rates do not properly adjust. Furthermore, levy growth is higher in years when the budget is based on mass reappraisals at 5.1 percent, as compared to just 2 percent in nonmass reappraisal years. However, Figure 3 also demonstrates that assessed values have largely been in accordance with estimates of fair market value growth in the areas. This suggests that demands for public services that accompany economic growth may be the main predictor of levy growth in a more sophisticated multivariate regression, the derivation of which is the subject of the next section. 4. MODEL DETERMINATION AND VARIABLE SELECTION Empirical Model The essence of the popular concern is that local officials can deviate from the median voter’s preferences in setting expenditure levels under the cover of rising property assessments. To test this rejection of the residual view, the model in this paper starts with the median voter demand model in the tradition of Borcherding and Deacon (1972), a model frequently employed in empirical work to test the degree of non-rivalry in local public expenditures.13 This model is motivated with the assumption of a decisive voter in area i receiving utility from the quantities of private (Xi) and public goods (gi). Using Gi to represent total public good provision, the degree of population (Ni) rivalry of the good or service 13 The model was similarly derived by Bergstrom and Goodman (1973). Other papers employing this model for public expenditures include McMillan et al. (1981), Edwards (1986), and Holcombe and Sobel (1995). 11 determines the individual level of consumption, resulting in gi=Ni-γGi, where γ is a congestion parameter. The decisive voter’s income (Ii) can be used to allocate expenditures across the two goods, with the resulting budget constraint of Ii=PxXi+TiPgGi, where Ti is the median voter’s share of the tax burden. Substituting giNγ in lieu of Gi into the budget constraint results in a demand equation of the form gi=gi(Ii,Px,Ti,Pg,N). Assuming that input prices to public service production are constant across the state, while allowing for individual voter taste characteristics to be represented as vector Vi, a constant elasticity 𝛾 𝜇 demand function can be defined as 𝑔𝑖 = 𝑉𝑖 (𝑇𝑖 𝑁𝑖 )𝛼 𝐼𝑖 . Substituting gi=Ni-γGi into the left-hand side and rearranging results in 𝜇 (1) 𝐺𝑖 = 𝑉𝑖 𝑇𝑖𝛼 𝑁𝑖𝜆 𝐼𝑖 , where λ=(1+α)γ. Since the quantity of government services is typically unknown, the literature proxies for these services using expenditures, implicitly assuming that there is a constant dollar per unit of public goods and services. The log-log form of equation (1) is then estimable using linear regression methods, and is adopted in this paper for the specific case of identifying local government expenditures. From an accounting perspective, balanced budgets require that government spending (Gi) in a given year equals the property tax levy (Li) plus revenue from other sources (Ri). In Virginia counties, these other nonproperty revenue sources are predominantly composed of intergovernmental transfers, various user fees, and cigarette taxes. Once the local government has identified revenue from all other sources it determines total spending by issuing the property tax levy. Median voter income is composed of annual income flow (Yi) and the income from the fair market value of their real property (Hi), although data limitations require us to proxy the latter with just the current market value.14 Income in this form is assumed to be the multiplicative function Iiμ=YiηHπ, with the intuition that the marginal propensity to spend on services may differ between income and their property values. Substituting this function into (1) and adding a temporal dimension results in the following logged empirical demand function for the property tax levy: 14 Ultimately, the implicit assumption is that the growth in the fair market value of the property will capture the influence and correlation of the income flow from properties in the behavior of the median voter. 12 (2) 𝑙𝑛𝐿𝑖𝑡 = 𝛽𝑙𝑛𝑉𝑖𝑡 + 𝛼𝑙𝑛𝑇𝑖𝑡 + 𝜆𝑙𝑛𝑁𝑖𝑡 + 𝜂𝑙𝑛𝑌𝑖𝑡 + 𝜋𝑙𝑛𝐻𝑖𝑡 + 𝛿𝑙𝑛𝑅𝑖𝑡 + 𝜀𝑖𝑡 . The expected signs are negative for tax price (α) and positive for housing values (π), population (λ), and income (η). The theoretical literature on the flypaper effect of other revenue sources suggests that the expected sign of Rit is ambiguous (Fisher, 1982; Hamilton, 1983; Hines and Thaler, 1995). Empirically, it is likely that there exist unobserved time invariant fixed effects, and as a consequence equation (2) will be first differenced to eliminate them: ̃𝑖𝑡 + 𝜂𝑙𝑛𝑌̃𝑖𝑡 + 𝜋𝑙𝑛𝐻 ̃𝑖𝑡 + 𝛿𝑙𝑛𝑅̃𝑖𝑡 + 𝜀̃𝑖𝑡 . (3) 𝑙𝑛𝐿̃𝑖𝑡 = 𝛽𝑙𝑛𝑉̃𝑖𝑡 + 𝛼𝑙𝑛𝑇̃𝑖𝑡 + 𝜆𝑙𝑛𝑁 Using tilde to represent the first differences, the model in equation (3) also squares with the general view in public finance that local public officials inherit the previous year’s budget, and then update it for the upcoming year to reflect new circumstances and information. This is done during the budgeting stage of the process, where policymakers have the opportunity to revise the levy, while anticipating the effect on the millage rate. As already described, critics of this process have claimed that property reassessments provide cover for public officials to increase the levy beyond that preferred by the constituency. If the residual view is correct, then reassessing property values will have no impact on the levy itself. To consider this possibility, we augment the model in equation (3) with the first differenced log of assessed values (AV) and a dummy variable indicator for the reassessment (A). ̃𝑖𝑡 + 𝜑(𝐴𝑖𝑡 × ̃𝑖𝑡 + 𝜂𝑙𝑛𝑌̃𝑖𝑡 + 𝜋𝑙𝑛𝐻 ̃𝑖𝑡 + 𝛿𝑙𝑛𝑅̃𝑖𝑡 + 𝜌𝐴𝑖𝑡 + 𝜃𝑙𝑛𝐴𝑉 (4) 𝑙𝑛𝐿̃𝑖𝑡 = 𝛽𝑙𝑛𝑉̃𝑖𝑡 + 𝛼𝑙𝑛𝑇̃𝑖𝑡 + 𝜆𝑙𝑛𝑁 ̃𝑖𝑡 ) + 𝜀̃𝑖𝑡 𝑙𝑛𝐴𝑉 The indicator Ait takes the value of one if the levy was set with assessed values following a mass reappraisal, whereas the continuous variable AVit is used to calculate the magnitude of change in assessed values used in setting the rate.15 The interaction between the two is employed to allow for the model to 15 Note that, while a mass reappraisal takes place between January and June of the calendar year, the millage rate derived from the property tax levy is not based on these updated values for the budgeting process until the next calendar year. So AVit is based on changes in assessed values relevant to the budget process, even though the assessor’s office may have already updated their parcel records. 13 distinguish the behavioral response between years with and without mass appraisals. The critical assumption implied here is that current period public service demands are a function of current fair market value appreciation, and that the median voter does not update their demands on a cycle that mimics the cycle between reassessments adopted for the budget process. Since some areas go as much as six years between mass reappraisals, the percentage increases can be orders of magnitude larger than the years between assessments, and so the adjustment of the rate may be substantially different in these two sets of years. The marginal effects of interest to testing the residual view are: (5) 𝜕𝑙𝑛𝐿̃𝑖𝑡 ̃ 𝑖𝑡 𝜕𝑙𝑛𝐴𝑉 (6) 𝜕𝑙𝑛𝐿̃𝑖𝑡 𝜕𝐴𝑖𝑡 = 𝜃 + 𝜑𝐴𝑖𝑡 ̃𝑖𝑡 = 𝜌 + 𝜑𝑙𝑛𝐴𝑉 Consider first the marginal effect of changes in assessed values, equation (5), during years where budgets are not based on mass reappraisals (Ait=0).16 The claim of the residual view is that rates fully adjust and there is no effect on the property tax levy, so that θ=0. In the strongest version of revenue-elasticity fiscal illusion, rates do not adjust at all so that increases in the base are automatically translated into new spending (θ=1). In years with mass reappraisals (Ait=1) this intuition on θ is unchanged, but it becomes a test of 𝜃̂ + 𝜑̂ = 0 for the residual view and 𝜃̂ + 𝜑̂ = 1 for critics. In principle, however, any substantive magnitude between zero and one demonstrates some amount of support for fiscal illusion in the reassessment process. There is no obvious expected sign for φ, but it is likely negative because of the constant elasticity implied by the log-log specification. Since the percentage change in assessed values are often orders of magnitude larger than those in the intervening years, the levy-growth responsiveness might be smaller in percentage terms than in non-mass reappraisal years. In equation (6), the marginal effect on the levy of a mass reappraisal is provided. Just to illustrate the intuition of this marginal effect, suppose taxable assessed value growth was zero following mass ̃𝑖𝑡 = 0; this would be the case if the appraisal only served to redistribute assessed reappraisal, so that 𝑙𝑛𝐴𝑉 16 Assessed values can change between reappraisals due to appeals, property improvements, and land use changes. 14 values across parcels. If the mass reappraisal allows for a form of fiscal illusion where taxpayers attribute their new tax bill solely to the reassessment, then local politicians could increase the levy and ρ would become positive.17 This was the specific test conducted by Bloom and Ladd (1982) and Ladd (1991), with the exception that the model employed here controls for factors other than the mass reappraisal. The full marginal effect in equation (6) also allows for the interaction with total assessed value growth so that it can possibly vary by magnitude of the assessment growth. Variable Definition and Data While the range of available data slightly differs across the variables, all series hold in common the 2000 to 2008 period, and therefore all summary statistics and regression estimates are based on this time period. Virginia has 134 cities and counties, but three of them (Alleghany County, Newport News City, and York County) are excluded because they exchanged territory in 2001, causing large reported changes in several key variables. All dollarized variables are inflation-adjusted to 2005 equivalent prior to any transformations. Real property tax levies and other sources of revenue were obtained from the Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts. The school-age share of the population, share of the population over age 65, and racial homogeneity are included as regressors in equation (4) to capture the effect of changing voter characteristics (𝑉𝑖𝑡 ). These are all common demographic variables of interest to the literature on demand for public services (e.g. Alesina et al, 1999; Lind, 2007; Fletcher and Kenny, 2008). Also included is the share of housing units which are owner occupied, as there is some support for “renter illusion” that may cause renters to not recognize the full cost of services financed by property taxes (Bergstrom and Goodman, 1973; Blom-Hansen, 2005).18 Annual population and housing unit estimates are provided by the U.S. Census, as are the estimates by age and race. Information on assessed values and the true fair The interpretation of ρ is that the implementation of a mass reappraisal increased the levy growth rate by (ρ x 100) percent. 18 We are grateful to an anonymous referee for suggesting the owner-occupied and school age children share as additional control variables. 17 15 market value of property is provided as part of the annual assessment sales ratio studies conducted by the Virginia Department of Taxation, and typically represent about three to four percent of the total parcels located in the state. Annual estimates of median adjusted gross household income are provided by the Virginia Department of Housing and Community Development. This measure of median household income had a change in definition for 2008, causing a large statewide increase in local estimates of income, and as a result time fixed effects are included in every model specification. The preferred measure of the median voter tax share typically used in empirical studies is the median assessed value as a share of total assessed values, with the assumption being that the median value approximates the median, or decisive, voter. Unfortunately, median assessed value is not available for any year except 2000, so instead we use the share of median income divided by total personal income in the county as a proxy for the tax share.19 Both the ideal and the employed measures of tax price implicitly adopt the view that it is only the residential tax price that is considered by local public officials, and that consequently non-residential tax prices are not influential. 5. ESTIMATION RESULTS Main Results Estimates of equation (4) are provided in Table 2 with alternative restrictions on the main variables of interest, and all specifications include year fixed effects. Breusch-Pagan diagnostics for heteroskedasticity supported the use of robust standard errors, which have been clustered by county. The control variables generally take the expected signs. The point estimates across the specifications in Table 2 indicate that a one percent increase in income growth was correlated with about a 0.30 percent increase in the property tax levy change. A one percent increase in population growth was 19 A pairwise correlation between the preferred median tax share and the proxy variable employed in the paper was 0.95 in 2000, which was the only year such a correlation could be computed. 16 correlated with roughly a 0.10 percent increase in the levy, while a percentage increase in the median tax share was correlated with about a 0.30 percent decline. The negative sign on median tax share, which proxies for the price to the median voter for public goods, is consistent with the existence of a downward sloping voter demand curve. Together, the population and tax price point estimates indicate that the Samuelson “publicness” index of the spending is between 0.51 and 0.40, roughly midway between a pure public and pure private good.20 Revenue from other non-property sources was positive and statistically significant, consistent with a complementary correlation with property tax revenue. The demographic variables were not statistically significant. The estimates of Table 2 also indicate that a one percent increase in the growth of the fair market value of property increases the property tax levy by a statistically significant 0.04 to 0.07 percent. This is consistent with the notion of wealth effects, where property owners support more public spending as the value of their assets increase, but is also a qualitatively small effect.21 In specifications B-E, variables capturing the effect of changing taxable assessed values are included, with the estimates of the full model in equation (4) appearing in specification E. As described earlier in this paper, changes in taxable values of property differ from the fair market value in important ways. First, the biggest changes in assessed values appear in years with mass reappraisals, which differ in frequency across areas. This causes the changes in assessed values to be more volatile since the reappraisals must reflect property value growth in all the intervening years. Secondly, taxable assessed values differ from fair market value by various property exemptions. In addition, assessor errors can result in assessment-to-sale price ratios that differ both over time and across areas. Finally, assessed value changes are not reflected in millage rates until the budget of the next fiscal year. There is some remaining multicollinearity between fair market and 20 As derived in Borcherding and Deacon (1972) and discussed in the model derivation section, the Samuelson index of publicness is given as the coefficient on population divided by one plus the coefficient on tax price. From column E of Table 2, this calculation is 0.280/(1-0.304)=0.401. The highest Samuelson index in Table 2 is 0.51 in column A. 21 There is nothing about the institutional design in Virginia that allows us to infer that the coefficient on the fair market value growth of property can be interpreted as a causal estimate of property wealth effects. It serves only to capture the accumulated wealth effects from economic growth that are not otherwise captured by the other variables. 17 assessed values, but it is relatively weak with variance inflation factors of 10. Multicollinearity is not particularly troubling here since both variables have high levels of statistical significance. The specifications in B-E of Table 2 are all supportive of some amount of fiscal illusion that would violate the residual view. Regardless of the specification, growth in assessed values and mass reappraisals are statistically significant determinants of property tax levy growth. From specification E it can be seen that in those years without mass reappraisals (A=0), a one percent increases in assessed values result in a statistically significant 0.068 percent increase in the property tax levy. For a 3.2 percent increase in assessed value growth, the observed sample mean, there is a 0.21 percent increase in the property tax levy, a magnitude that is 7 percent of the mean observed levy growth in the sample.22 The marginal effect in equation (5) of assessed value growth during mass reappraisals (A=1) diminishes to 0.051 and loses statistically significance.23 At best, it seems there is a very small amount of fiscal illusion from assessed value growth that is statistically significant, but it is substantively small and thus consistent with the revenue neutral adjustments in the property tax rate predicted by the residual view. In evaluating the marginal effect of a mass reappraisal, provided in equation (6), we first consider the case with zero assessment growth (Δln(Assessed Values)=0) where the potential for fiscal illusion would come from a zero-sum redistribution of the property assessments across individual owners. The point estimate in column E of Table 2 suggests that mass reappraisals increase the levy growth rate by 1.5 percent.24 This effect shrinks by 0.017 percent for every one percent above zero assessment growth, though this is not statistically significant. In Table 3, specifications are alternated with the inclusion of area and year fixed effects. Although the influence of time invariant omitted variables relevant to explaining the levels of the variables would have been eliminated with first differencing, the specifications with the inclusion of area fixed effects discard the influence of any remaining omitted variables which might affect the rate of 22 Calculations: 3.2x0.068=0.218; 0.218/3.0 = 0.07 (7%). Calculation: 0.068-0.017=0.051. 24 Calculation: 100 x 0.015=1.5%. 23 18 change in the levy. Both appraisals and assessed value growth retain at least 5 percent level of statistical significance, with magnitudes remaining relatively unchanged from those presented in Table 2. The primary consequence of including fixed effects is the sensitivity of statistical significance of the other variables. The main findings presented in Tables 2 and 3 demonstrate there are some detectable amounts of fiscal illusion that is statistically significant, but substantively small.25 The primary interpretation is that mass reappraisals provide some cover for politicians to raise levies, but the aggregate growth in taxable assessed values is largely irrelevant. In essence, the politicians can raise a small amount of additional revenue through the levy under the guise that most owners will simply attribute it to their new property reassessment, and without the cover of the mass appraisal that revalues the properties across the board this is much harder to do. Our findings are also substantially smaller than those found in the most comparable previous literature on fiscal illusion with respect to property reassessments. Bloom and Ladd (1982) found that mass reappraisals were associated with a 5.1 percent levy increase in Massachusetts, but these findings had no other controls for economic growth and mass appraisals were likely determined endogenously to annual levy growth. Ladd (1991) found the impact of assessments to increase property tax levies by an additional 3 to 8 percent in North Carolina counties where reassessments were likely exogenous in their timing, but once again there were no controls for economic growth. Our approach finds a substantively smaller amount of levy growth at approximately 1.5 percent. Specification Checks In the results presented in Tables 2 and 3, the assumption was made that wealth effects arising from the median voter came from the true fair market value of their property, which is derived from the state’s annual sales ratio study of assessment accuracy. An alternative possibility is that the owner’s primary 25 Interestingly, although the detectable amount of fiscal illusion is small, the magnitude is comparable to the coefficient size on fair market value appreciation, although we cannot make comparable claims of causality. 19 information source for property value is their assessed value.26 To explore this possibility we take advantage of a difference in timing between when the assessed values are known to the property owner (Assessed Values†) and when they are employed for the purpose of tax rate setting (Assessed Values‡), a lag that exists to allow for an appeal period to occur. As previously described, the latter assessed values is the same measure previously employed in the measure of Assessed Value growth in Tables 2 and 3 since that was the relevant opportunity for taking advantage of voter fiscal illusion. Table 4 and Table 3 differ only in that the growth in fair market property values has been replaced with the growth in assessed values as they are known to the property owners. We can see that the assessed value growth known to the owners (†) is positive and statistically significant, albeit with smaller magnitudes than when the counterpart measure of fair market value growth was used in Table 3. More importantly for our purposes, however, the magnitudes and statistical significance for the variables of interest of interest, Mass Reappraisal and Assessed Values‡, were virtually unchanged. The results in comparing Table 4 to Table 3 also present some evidence on another possible limitation of the test. If there is error in the measure of fair market value, the positive correlation between assessed value and market value appreciation could introduce some positive bias to the estimated coefficient on the assessment variables. This correlation is weakened by the budgetary lag in adopting the assessed values used for rate-setting, but Table 4 also reveals that when fair market value is replaced by contemporaneous assessed value growth the coefficients are virtually unchanged. Since the contemporaneous assessed value carries an even larger difference from market value, it seems likely that this potential bias is small. Though not presented, some additional sensitivity checks are discussed in the remainder of this section and are available upon request. For brevity, all of the sensitivity assumptions will be compared to specification D of Table 3, the full model with both year and county fixed effects. The final year of the dataset, 2008, would have reflected adjustments to the budgets with the housing market crash towards the 26 We appreciate an anonymous referee who suggested this alternative possibility. 20 end of the 2007 calendar year. Estimating the model without 2008 data has virtually no effect on the results. The point estimate on mass reappraisals is 1.5 percent and is statistically significant at the 5 percent level, down from 1.7 percent with 1 percent significance. The coefficient on assessed value growth remains at 0.059 with a p-value below 0.05. One of the attributes of Virginia is that state law creates heterogeneity in the frequency of mass reappraisals. A potential limitation of this law, however, is that areas with more frequent mass reappraisals will carry more weight in the mean-centered parameter estimate on the Mass Reappraisal indicator. To examine the sensitivity of the results to this phenomenon, the full model with both area and year fixed effects was estimated with a weighted regression, where the weight was based on the inverse frequency of their number of mass reappraisals in the sample. Comparing to the unweighted regression in specification D of Table 3, the point estimate on Mass Reappraisal increased to a 2.3 percent increase in property tax levies that was statistically significant at the five percent level. The point estimate on assessed value growth was 0.055, only slightly lower than in the unweighted regression, though its statistical significance fell below the 5% level. Finally, there is a considerable literature in local public finance on tax competition among governments (for e.g., see Wilson, 1999; Brueckner and Saavedra, 2001). Using spatial econometrics to allow for neighbor’s property tax levy growth as another control variable demonstrated no substantive difference in the main variables of interest, and the statistical significance of the spatial lag carried a p-value of just 0.10.27 Alternative specifications of non-property revenue were included or replaced for the one presented, including separate controls for state and federal transfers, but this had no substantive effect on our variables of interest and the r-squares were virtually unchanged. Finally, as previously described, three areas were excluded from the regression because they changed territorial boundaries with each other in 2000 to 2001, causing relatively large swings in several of their variables. Including them in the 27 The spatial weight matrix most favorable to a finding of spatial dependence was the first-order contiguity matrix, for which the tax mimicking parameter was about 0.07. The result was estimated using the maximum likelihood approach described in LeSage and Pace (2009). We are grateful to an anonymous referee for suggesting this robustness check. 21 regression, however, did not affect the main variables of interest within the rounding tolerance of the reported result in specification D of Table 3. 6. CONCLUDING REMARKS The residual view of the property tax is that changes in assessed values have no direct influence on the amount of revenue raised through real property taxation because rates adjust as a matter of arithmetic (Netzer, 1964). Critics of property taxes suggest that the reassessment process creates a form of fiscal illusion, analogous to the revenue elasticity hypothesis (Oates, 1975; Dollery and Worthington, 1996). The few papers which have previously tested these competing views directly, however, have considerable shortcomings with respect to a causal identification approach. Particularly problematic for the previous literature has been the inability to control for economic growth in an area that may be associated with changes in assessed values, as well as endogeneity in the decision to conduct reassessments. Using 2000 to 2008 data from Virginia cities and counties, this paper provides the clearest evidence to date on the validity of the residual view. We argue that the institutional structure results in a reassessment cycle that is exogenous to a given year’s levy growth, and we are able to control for confounding economic growth factors. Our findings suggest that there is a statistically significant but analytically trivial amount of fiscal illusion that allows for levy growth in response to increases in taxable assessed values. Mass reappraisals, on the other hand, do provide some cover for politicians to hide levy increases on the order of about 1.5 percent, but the aggregate growth in taxable assessed values that occurs due to the reassessment is largely irrelevant. We speculate that the mass reappraisals allow politicians to raise a small amount of additional revenue because most owners will likely ascribe changes in their tax bill primarily to their new assessments. Our finding on mass reappraisals is substantially smaller, however, than the most comparable literature found in Bloom and Ladd (1982) and Ladd (1991), which produced estimates of 5.1 and 3 to 8 percent, respectively. 22 Despite the generally high visibility of the property tax to which many scholars attribute to its unpopularity, this paper joins Cabral and Hoxby (2010) in finding evidence that this instrument is not completely exempt from fiscal illusion. To the extent the mass reappraisals allow for politicians to push levy growth above trend, this fiscal illusion detracts from the median voter theory as a descriptive theory of local government. The evidence presented here, of course, is qualified by the external validity of applying Virginia results to other states. States like California, Florida, and Michigan place limits on the ability of local governments to raise revenue through the property tax, which may induce local governments to strategically raise levies beyond current median voter demands in anticipation of being unable to raise levies again in the future. It is possible that additional transparency laws may help circumvent this phenomenon. Some states have also adopted “Truth in Taxation” laws that apply to the property tax, which can include the publication of important ballot information or direct mailings of budget information (Youngman and Malme, 2005). In Virginia, cities and counties must only publish an announcement in the local paper if levies are to increase more than one percent in a particular year. It is possible that strengthening such laws further, perhaps by informing property taxpayers what their individual liability would have been under the previous year’s levy, might assist in overcoming the fiscal illusion that occurs in mass reappraisal years. Limiting the discretionary power local politicians have over general purpose budgets, such as by requiring voter approval for significant tax levy increases, might also be a step towards constraining such behavior. REFERENCES Alesina, Alberto, R. Baqir, and William Easterly. 1999. Public Goods and Ethnic Division. Quarterly Journal of Economics 114: 1243-84. Alm, James, Robert D. Buschman, and David L. Sjoquist. 2011. Rethinking Local Government Reliance on the Property Tax. Regional Science and Urban Economics 41:320-331. Bergstrom, T. C, and R. P. Goodman. 1973. Private demand for public goods. American Economic Review 63: 280-296. Blom-Hansen, Jens. 2005. Renter Illusion: Fact or Fiction? Urban Studies 42(1): 127-40. 23 Bloom, Howard S., and Helen F. Ladd. 1982. Property Tax Revaluation and Tax Levy Growth. Journal of Urban Economics 11 (1):73-84. Borcherding, Thomas E., and Robert T. Deacon. 1972. The Demand for Services of Nonfederal Governments. American Economic Review 62 (Dec.):891-901. Brueckner, Jan K. and Luz A. Saavedra. 2001. Do Local Governments Engage in Strategic Property-Tax Competition? National Tax Journal 54(2): 203-229. Cabral, M. and C. Hoxby. 2010. The Hated Property Tax: Salience, Tax Rates, and Tax Revolts. Stanford University Working Paper. Retrieved from http://www.stanford.edu/~mcabral/Tax_Salience.pdf. Cornia, Gary C. and Lawrence C. Walters. 2006. “Full Disclosure: Controlling Property Tax Increases During Periods of Increasing House Values.” National Tax Journal 59 (September): 735-49. Doerner, William M., and Keith R. Ihlanfeldt. 2011. House Prices and City Revenues. Regional Science and Urban Economics 41:332-342. Dollery, Brian E. and Andrew C. Worthington. 1996. The Empirical Analysis of Fiscal Illusion. Journal of Economic Surveys 10(3): 261-297. Dougan, W.R. and Kenyon, Daphne A. 1988. Pressure Groups and Public expenditures: The Flypaper Effect Reconsidered. Economic Inquiry 26: 159-70. Edwards, J. H. Y. 1986. A note on the publicness of local goods: Evidence from New York State municipalities. Canadian Journal of Economics 19: 568-573. Faulk, Dagney. 2004. How We Got Here from There: A Chronology of Indiana Property Tax Laws. Indiana Business Review 79(2): 1-3. Fletcher, Deborah and Lawrence W. Kenny. 2008. The Influence of the Elderly on School Spending in a Median Voter Framework. Education Finance and Policy 3(3): 283-315. Fisher, Ronald C. 1982. Income and grant effects on local expenditure: The flypaper effect and other difficulties. Journal of Urban Economics 12 (3):324-45. ———. 2007. State & Local Public Finance, 3rd Edition: Thomson South-Western. Hamilton, Bruce W. 1983. The Flypaper Effect and Other Anomalies. Journal of Public Economics 22 (3):347-361. Hines, James R., and Richard H. Thaler. 1995. Anomalies: The Flypaper Effect. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 9 (4):217-226. Holcombe, R. G., and R. S. Sobel. 1995. Empirical evidence on the publicness of state legislative activities. Public Choice 83: 47-58. Ladd, Helen F. 1991. Property Tax Revaluation and Tax Levy Growth Revisited. Journal of Urban Economics 30 (1):83-99. LeSage, James P. and R. Kelley Pace. 2009. Introduction to Spatial Econometrics. CRC Press: Taylor & Francis Group. Lind, Jo Thori. 2007. Fractionalization and the Size of Government. Journal of Public Economics 91: 5176. Lutz, Byron F. 2008. The Connection Between House Price Appreciation and Property Tax Revenues. National Tax Journal 41 (3):555-572. Lutz, Byron, Molloy Raven, and Hui Shan. 2011. The Housing Crisis and State and Local Government Tax Revenue: Five Channels. Regional Science and Urban Economics 41:306-319. Martin, Isaac William. 2008. The Permanent Tax Revolt: How the Property Tax Transformed American Politics. Stanford: Stanford University Press. McMillan, M. L., R. W. Wilson and L. M. Arthur. 1981. The publicness of local public goods: Evidence from Ontario municipalities. Canadian Journal of Economics 14: 596-608. Mikesell, John L. 1978. Property Tax Assessment Practice and Income Elasticities. Public Finance Quarterly 6 (1):53-63. ———. 1980. Property Tax Reassessment Cycles: Significance for Uniformity and Effective Rates. Public Finance Review 8 (1):23-37. ———. 2011. Fiscal Administration: Analysis and Applications for the Public Sector. 8 ed. Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. 24 Netzer, Dick. 1964. Income Elasticity of the Property Tax: A Post-Mortem Note. National Tax Journal 17 (2):205-207. Oates, Wallace E. 1975. Automatic Increases in Tax Revenues – The Effect on the Size of the Public Budget. In W.E. Oates (ed) Financing the New Federalism: Revenue Sharing Conditional Grants and Taxation. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. Oates, Wallace E. 1979. Lump-sum Intergovernmental Grants have Price Effects. In P. Mieszkowski and W. Oakland (ed) Fiscal Federalism and Grants-in-Aid. Washington D.C.: The Urban Institute. Robert D. Lee, Jr., Ronald W. Johnson, and Phillip G. Joyce. 2008. Public Budgeting Systems. Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Inc. Smith, Adam. 1776. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. New York: The Modern Library. Stine, William F. 2010. Estimating the Determinants of Property Reassessment Duration: An Empirical Study of Pennsylvania Counties. Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy 40 (2):143-159. Wilson, John Douglas. 1999. Theories of Tax Competition. National Tax Journal 52(2): 269-304. Youngman, Joan, and Jane Malme. 2005. Stabilizing Property Taxes in Volatile Real Estate Markets. Lincoln Instiute of Land Policy: Land Lines 17 (3). 25 Figure 1: Growth of U.S. Housing Prices and Local Property Tax Revenue, 1997-2009 2.50 1997=1.0 2.00 1.50 1.00 0.50 0.00 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Housing Price Index Local Property Tax Revenue Data: Housing Price Index (Federal Housing Finance Agency); Local Property Tax Revenue (U.S. Census of Government Finance). 26 70 20 30 40 50 60 Property Tax Levy (Millions, 2005$) 1 .8 .6 .4 .2 0 Property Tax Millage Rate Figure 2: Average Local Property Tax Rates Versus Real Property Tax Levies in Virginia, 1997-2009 1995 2000 2005 2010 Year Property Tax Millage Rate Property Tax Levy (Millions, 2005$) Note: Levy data from Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts; millage rate from Virginia Department of Taxation (available only starting in 1998). 27 Figure 3: Average Local Assessed Values Versus Estimated Fair Market Values for Real Property in Virginia, 1998-2009 Notes: Data from Virginia Department of Taxation 28 Table 1: Summary Statistics and Variable Description Variable Δln(Property Tax Levy) Δln(Non Property Revenue) Δln(Fair Market Property Value) Δln(Median Tax Share) Δln(Population) Δln(Median Household Income) Δln(Share School Age) Δln(Share Age 65+) Δln(Share Owner Occ.) Δln(Racial Homogeneity) Mass Reappraisal Δln(Assessed Values) Mean Std.Dev. Min Max 0.030 0.067 -0.356 0.510 0.005 0.069 -0.478 0.396 0.052 0.133 -0.234 0.814 0.022 0.153 -0.502 1.434 0.010 0.025 -0.090 0.193 0.034 0.143 -0.528 1.417 -0.007 0.027 -0.232 0.272 0.012 0.101 -0.688 1.269 0.005 0.006 -0.034 0.074 -0.001 0.071 -0.650 0.620 0.321 0.467 0.000 1.000 0.032 0.234 -0.529 1.629 Sample Size: 1,172 Notes & Sources: All currency data deflated to real 2005 dollars prior to transformations; Δln(variable) indicates the year-over-year change in the natural log of the variable. Property Tax Levy: Total revenue to be raised from taxation of real property (Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts); Non Property Revenue: local revenue raised from all sources other than real property taxation (Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts); Fair Market Property Value: total true fair market value of all taxable properties as estimated in the state assessment-sale price ratio study (Virginia Department of Taxation); Median Household Income: median adjusted gross income from tax returns (Virginia Department of Housing and Community Development); Median Tax Share: median household income divided by total personal income in thousands of dollars (Bureau of Economic Analysis); Share School Age: Share of population that is age 5-19 (U.S. Census); Share Age 65+: population over age 65 divided by total population (U.S. Census); Share Owner Occ.: share of the housing units that are owner occupied (occupancy status and building permit data on residential construction from the U.S. Census); Racial Homogeneity: a Herfandahl-Hirschman Index of racial population composition between whites, blacks, Asians, American Indians, and miscellaneous divided by 10,000 (authors’ calculation from U.S. Census Data); Mass Reappraisal: dummy variable indicating that the year’s budget is based upon assessed values following a mass reappraisal (Virginia Department of Taxation); Assessed Values: total assessed values of taxable properties used in that year’s public budget, as estimated in the state assessment-sale price ratio study (Virginia Department of Taxation). Δln(M.H.I.)xY2008: interaction of median household income with year 2008 dummy to account for change in measurement. 29 Table 2: OLS Estimates of Property Tax Levy Growth for Virginia cities and counties with Year Fixed Effects, 2000-2008. Dep. Var.: Δln(Property Tax Levy) Δln(Non Property Revenue) Δln(Fair Market Property Value) Δln(Median Tax Share) Δln(Population) Δln(Median Household Income) Δln(M.H.I.)xY2008 Δln(Share School Age) Δln(Share Age 65+) Δln(Share Owner Occ.) Δln(Racial Homogeneity) A B 0.079** 0.075** C 0.082** D 0.079** E 0.079** (0.036) (0.035) (0.036) (0.036) (0.036) 0.041*** 0.053*** 0.072*** 0.072*** 0.073*** (0.015) (0.015) (0.015) (0.015) (0.015) -0.342*** -0.292*** -0.330*** -0.306*** -0.304*** (0.091) (0.088) (0.085) (0.084) (0.084) 0.341*** 0.280*** 0.307*** 0.282*** 0.280*** (0.095) (0.094) (0.091) (0.091) (0.091) 0.124 0.101 0.110 0.101 0.100 (0.116) (0.111) (0.109) (0.108) (0.107) 0.252*** 0.218*** 0.254*** 0.236*** 0.235*** (0.087) (0.084) (0.082) (0.082) (0.082) 0.087 0.037 0.070 0.047 0.045 (0.062) (0.061) (0.059) (0.060) (0.060) 0.021 0.014 0.010 0.008 0.009 (0.023) (0.023) (0.021) (0.022) (0.022) -0.074 0.121 0.049 0.128 0.173 (0.274) (0.285) (0.245) (0.256) (0.281) 0.000 0.005 0.005 0.006 0.006 (0.023) (0.022) (0.022) (0.021) (0.021) 0.014*** 0.015*** Mass Reappraisal 0.027*** (0.005) Δln(Assessed Values) (0.005) (0.005) 0.071*** 0.057*** 0.068*** (0.011) (0.011) (0.021) Mass Reappraisal x Δln(A.V.) -0.017 (0.024) Intercept 0.021** 0.012 0.020** 0.016* 0.016* (0.008) (0.008) (0.008) (0.008) (0.008) 2 0.107 0.140 0.159 0.166 0.167 R Notes: Sample size is 1,172, with 131 cross-sectional units. Statistical significance level indicated with *** (p<0.01), ** (p<0.05), * (p<0.1). Robust standard errors clustered by area reported in parentheses. All specifications include year fixed effects. 30 Table 3: Property Tax Levy Growth Determinants for Virginia cities and counties with Area and Year Fixed Effects, 2000-2008 Dep. Var.: Δln(Property Tax Levy) A Δln(Non Property Revenue) 0.064* Δln(Fair Market Property Value) Δln(Median Tax Share) Δln(Population) B C 0.079** 0.056 D 0.070* (0.035) (0.036) (0.037) (0.038) 0.071*** 0.073*** 0.056*** 0.058*** (0.015) (0.015) (0.015) (0.015) -0.198*** -0.304*** -0.044 -0.105 (0.073) (0.084) (0.083) (0.102) 0.401*** 0.280*** 0.254*** 0.105 (0.088) (0.091) (0.094) (0.095) 0.022 0.100 -0.176* -0.165 Δln(Median Household Income) (0.092) (0.107) (0.104) (0.132) 0.163*** 0.235*** 0.197*** 0.302*** (0.055) (0.082) (0.055) (0.087) 0.043 0.045 0.034 0.036 (0.065) (0.060) (0.072) (0.067) -0.001 0.009 -0.013 -0.003 (0.021) (0.022) (0.023) (0.024) 0.097 0.173 0.062 0.209 (0.277) (0.281) (0.304) (0.328) 0.008 0.006 0.000 -0.001 (0.023) (0.021) (0.026) (0.023) Mass Reappraisal 0.014*** 0.015*** 0.016*** 0.017*** (0.005) (0.005) (0.006) (0.006) Δln(Assessed Values) 0.070*** 0.068*** 0.060** 0.060** (0.021) (0.021) (0.025) (0.025) -0.019 -0.017 -0.020 -0.020 Δln(M.H.I.)xY2008 Δln(Share School Age) Δln(Share Age 65+) Δln(Share Owner Occ.) Δln(Racial Homogeneity) Mass Reappraisal x Δln(A.V.) (0.025) (0.024) (0.031) (0.031) 0.013*** 0.016* 0.017*** 0.026*** (0.003) (0.008) (0.003) (0.009) Area FE? No No Yes Yes Year FE? No Yes No Yes Intercept 2 0.135 0.167 0.088 0.127 R Notes: Sample size is 1,172, with 131 cross-sectional units. Statistical significance level indicated with *** (p<0.01), ** (p<0.05), * (p<0.1). Robust standard errors reported in parentheses; specifications without area fixed effects are clustered by area. For models with area fixed effects R2 , reported is the within-R2 . 31 Table 4: Property Tax Levy Growth Determinants for Virginia Cities and Counties with Area and Year Fixed Effects, 2000-2008 Dep. Var.: Δln(Property Tax Levy) A Δln(Non Property Revenue) 0.067* Δln(Assessed Values)† Δln(Median Tax Share) Δln(Population) B 0.080** C 0.058 D 0.070* (0.035) (0.036) (0.037) (0.038) 0.028*** 0.032*** 0.022*** 0.026*** (0.007) (0.008) (0.008) (0.008) -0.206*** -0.320*** -0.041 -0.111 (0.074) (0.085) (0.084) (0.104) 0.425*** 0.301*** 0.264*** 0.115 (0.089) (0.092) (0.094) (0.096) 0.041 0.125 -0.171 -0.156 Δln(Median Household Income) (0.093) (0.108) (0.106) (0.134) 0.144*** 0.226*** 0.184*** 0.298*** (0.055) (0.083) (0.056) (0.087) 0.034 0.037 0.026 0.029 (0.066) (0.060) (0.073) (0.066) -0.005 0.007 -0.018 -0.005 (0.021) (0.023) (0.024) (0.025) 0.140 0.216 0.079 0.229 (0.292) (0.293) (0.312) (0.336) 0.008 0.006 0.000 -0.002 (0.024) (0.022) (0.026) (0.024) Mass Reappraisal 0.015*** 0.015*** 0.016*** 0.017*** (0.005) (0.005) (0.006) (0.006) Δln(Assessed Values)‡ 0.066*** 0.066*** 0.057** 0.058** (0.022) (0.021) (0.025) (0.025) -0.019 -0.018 -0.019 -0.021 Δln(M.H.I.)xY2008 Δln(Share School Age) Δln(Share Age 65+) Δln(Share Owner Occ.) Δln(Racial Homogeneity) Mass Reappraisal x Δln(A.V.)‡ (0.025) (0.024) (0.031) (0.031) 0.015*** 0.017** 0.019*** 0.027*** (0.003) (0.008) (0.003) (0.009) Area FE? No No Yes Yes Year FE? No Yes No Yes Intercept 2 0.129 0.162 0.084 0.124 R Notes: Sample size is 1,172, with 131 cross-sectional units. Statistical significance level indicated with *** (p<0.01), ** (p<0.05), * (p<0.1). Robust standard errors reported in parentheses; specifications without area fixed effects are clustered by area. For models with area fixed effects R2 , reported is the within-R2 . †- indicates assessed value growth at the time in which the households are informed of them; ‡ indicates assessed values when used for determining millage rate. 32