Thao Naly Thao Professor Bowers WRI 1 SEC 52 19 October 2013

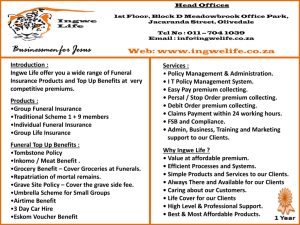

advertisement

Thao 1 Naly Thao Professor Bowers WRI 1 SEC 52 19 October 2013 Beauty Within Death “Move out of the way! The guests are here! The guests are here!” A couple of men quickly cleared the aisle from the casket all the way to the doorway. The crowd quickly scrambled to the sides of the aisle. Moments later a group of women and men with napkins formed two lines behind a qeej player by the doorway. Suddenly the qeej player plays his pipe instrument called the “qeej.” By the first stanza or two, the group behind him burst into tears. The mourning of the group filled the whole room. I watched my mother walk toward the casket while the drum continued to beat. It beat once every first and third downbeat in a four-four time signature and then quickly ascended to every down beat to every quarter beat. With animal sacrifices, drum beats, the sound of the qeej, and the singing of a man, the Hmong culture is probably one of the strangest when it comes to funeral traditions. Although most funerals are for lamenting the death of a loved one, this is not the only case for Hmong funerals. In addition to lamentation, traditional Hmong funerals start the death part of the human soul cycle (Yang). If the funeral is not accurately managed, the soul will return to the family bringing bad luck or consequences (Morrison). For example, a family member might get really sick where a soul calling ritual performed by a shaman would be required. Hmong funeral traditions may be one of the strangest traditions but it definitely has some of the most beautiful symbols and meanings. Thao 2 Hmong funerals dates back to the 1890s where the Hmong people once lived in China (Falk). The tradition has been brought down South to Thailand and Laos then across seas to Australia and the United States (Falk). This expansion of tradition is the effect of the Hmong people continually migrating to escape the Qing dynasty as well as other wars (Hmong People). According to Falk, the Hmong’s funeral tradition is most similar to the non-Han tribal people of southern China. Both saw the funeral process as a journey to their ancestors in the spiritual world and to rebirth (Falk). This is why Hmong funerals usually last twenty four hours up to three or four days (Hmong Funeral Customs and Traditions). The most is nine days and nights (Morrison). The length of the funeral has to do with the age of the deceased. There is no chart that shows the length of a funeral according to the age. Generally, it is “two days for a child and four days for an adult” (Morrison). It is longer for adults because they have lived a longer life meaning the person who is playing the qeej and the spiritual translator would take a longer time showing the soul of the deceased back home to its birthplace than it would for a child. The journey of the soul is led by a rooster, the words of the qeej, and a spirit translator. The journey begins with a death chant full of “flowery metaphor and analogies” called “Qhuab Kev” performed by the spiritual translator (Falk). In English it is literally “Showing the Way” death chant (Falk). This part of the ritual is very important because the Hmong people believe that in order for the soul to be well prepared for the journey back home and for the next life, necessities and luxuries such as livestock and gold must be sacrificed (Hmong Funeral Service Rituals: Summary & Reference Guide). There are many different songs performed by the spiritual translator. Everything you sacrifice to the dead has its’ own song that needs to be sung. For example, when sacrificing an Thao 3 animal, a rope is tied to the animal and the other end is tied to the dead. A chant by the spirit translator or a song is played by the qeej. Necessities for the journey is provided for the deceased during this time frame. These necessities range from guidance, food, clothing, money, and animals as well as the creation of the world including death (Falk). Before the qeej starts the journey of the dead, the translator would provide the dead with these words of wisdom: “Oh the dead, you are well dressed and you will soon be on your way to your grandparents' world. A spirit rooster will crow and your rooster will not reply. This is not your grandparents' place. People will try to deceive you and lead you to the edge of the mountains and the cliffs to try to make you fall into the wrong place. If your rooster crows and the spirit rooster replies then this is your grandparents' place. You can perch on the edge of their coffins. If the spirit rooster crows and your rooster replies, then this is your grandparents' place. You can perch on the edge.” (Falk) When the rooster of the soul replies to the spirit rooster, the translator would provide the soul of the deceased with the below stanza, a response to the “ancestors’ queries about its travelling companion with riddles: Your ancestors will say, “Who showed you the way here? You will answer: ‘It was a fellow with a face as big as a fan and eyes like saucers, feet like ox’s hooves and taking up as much room as an ox when he lies down’. Your ancestors will say next, “How can we follow his tracks? If we call him, will he hear? Will we be able to catch him up on horseback?’ You must say: ‘He can hear no call. He lead me here this year. And left again last year. He can hear no call.’ Thao 4 Your answers will say ‘Well can’t we follow his tracks?’ You must answer: ‘No one can follow his tracks, the weather was dry when he came, when he left, it was raining and his tracks were all washed away’. When he came, the reeds parted like swords, the leaves of the grass parted like spearheads. Now he’s gone, the reeds are stock still, the grass blocks the way, unmoving. Partridges and pheasants scratched the ground, leaves cover the path. No one can find his tracks, no one can catch him up on horseback. Partridges and pheasants pecking at the leaves must have covered his tracks’. You will say : ‘He sent me this year, he left again last year. He can hear no call’. You will say that when you came you had shoes and you crossed a bridge,, he had no shoes he came by the mountain road and left again over the slippery rocks. You will say you can see if the water is clear, but not if the water is muddy” (Falk). It is very dangerous for the spirit translator and the qeej player to remain between the little space separating the world of life and the world of spirits (Falk). Therefore it is the duty of the deceased to protect these translators from the dead by answering the spirits with these riddles to their questions so the dead will not be able to follow them back (Falk). After the spirit translator is finish providing the soul with necessities and instructions, the qeej player comes into play. They both alternate providing necessities and instructions to the dead. The qeej player plays a “free-reed multiple pipe musical instrument” called the qeej (Morrison). It is not played with any other instrument other than the drum on some occasions (Morrison). Information about when the drum accompanies the qeej is not available. The Lao and the Thai people have pipes similar to this one but they all serve different purposes (Morrison). According to Morrison, the pipes for the Laos and Thai people are for musical Thao 5 entertainment. For the Hmong people, it is a voice that speaks with the spirit world (Morrison). This is how the qeej player guides the soul of the deceased to its ancestors. The songs being played at funerals by the qeej cannot be played anywhere else other than the funeral because it is so powerful that precautions must be taken when being played (Kue). For example, a living soul can be sent unintentionally to the deceased’s ancestors in the spiritual world if it is played in a private home (Kue). “Song of Expiring Life” is the English translation of the songs played by the qeej master. The qeej speaks and asks “why has this person died? Who or what caused it? And do you know why there is such a thing as life and death on this earth?” (Morrison). The story of the creation of life and death is played by the qeej as well as the cycle of life, God, and the Devil. How the deceased passed is also mentioned in this part of the ritual. For example if a deceased passed due to poisoning their own self, a verse like this one would be played by the qeej; “You are born into this world, Have decided to overdose your self Going back to your ancestor They will not accept you…” The “Song of Expiring Life” played by the qeej master leads to another song. I could not find any non-primary sources about what this song is called, only primary sources. The song that follows the “Song of Expiring Life” is a song that builds a home for the dead (Kue). The home is the grave the dead will rest in. The song is played immediately before moving the casket from the funeral home to the graveyard. At the graveyard, the dead is buried with three sets of black and white clothing. Colors like green and red are prohibited on the clothes (Hmong Funeral Service Rituals: Summary & Thao 6 Reference Guide). According to Hmong Funeral Service Rituals, it is seen to cause illness to the dead. Families, relatives, and friends then take turns throwing flowers and shoveling two shovel full of dirt onto the casket. To the Hmong, it is seen as helping to build the house for our loved one who had passed. Hmong funeral customs and traditions may be one of the strangest traditions yet but it provides the most beautiful symbolic funerals. Hopes of reuniting with everyone you had loved that had passed makes death a beautiful idea in the Hmong community instead of frightening. Of course no one likes death but a meaning more beautiful than death itself can exist. The beautiful thing that exists are the beliefs of Hmong funerals. Thao 7 Works Cite Falk, Catherine. “Upon Meeting the Ancestors: The Hmong Funeral Ritual in Asia and Australia.” Hmong Studies Journal Fall 1996: n. pg. Web. 19 Oct. 2013. “Hmong Customs and Culture.” Wikipedia. 11 Oct. 2013. Web. 13 Oct. 2013. “Hmong Funeral Customs and Tradition.” Hmong Funerals. Web. 19 Oct. 2013. “Hmong Funeral Service Rituals: Summary & Reference Guide.” Funeralwise LLC. Web. 19 Oct. 2013 “Hmong People.” Hmong Culture. Web. 19 Oct. 2013. Kue, Jerry. “Hmong Funeral.” CSU Chico. 8 Dec. 1997. Web. 13 Oct. 2013 Morrison, Gayle. “The Hmong Qeej: Speaking to the Spirit World.” Hmong Studies Journal Spring 1998: n. pg. Web. 18 Oct. 2013. Yang, Yeng. “Hmong Americans: Dying and Death Ritual.” SFSU Yellow Journal. Web. 19 Oct. 2013.