Document G: An assessment of the Hundred Day Reforms (original)

advertisement

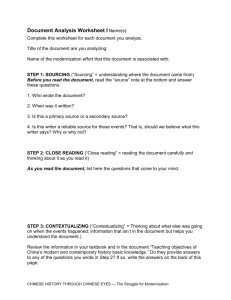

Modernization Lesson 2: The 1898 Hundred Day Reforms Contents of this file Notes on implementing the lesson Document A: The main actors in the 1898 Hundred Day Reforms Document B: Reformer Kang Youwei’s first audience with the Guang Xu emperor, June 16, 1898 (modified) Document C: One of reformer Kang Youwei’s appeals to the Guang Xu emperor during the summer of 1898 (original) Document D: September 12, 1898, decree by the Guang Xu emperor concerning reform of the imperial government (original) Document E: Reform decrees issued by the Guang Xu emperor (modified) Document F: The empress dowager smashes the Hundred Day Reforms (original) Document G: An assessment of the Hundred Day Reforms (original) Sources Notes on implementing the lesson Students should complete Contextualization Lesson 1 and Modernization Lesson 1 before beginning this lesson. Teachers can review the file “1 Introduction to the Unit” for details on how this lesson fits into the unit “China: The Struggle for Modernization.” Like all lessons in this unit, this lesson implements the Reading Like a Historian pedagogy developed by the Stanford History Education Group. Teachers should be familiar with the concepts of sourcing, contextualizing, close reading, and corroborating. Further information is available at sheg.stanford.edu/?q=node/45. The ultimate goal of this lesson is for students to identify the goals of the 1898 Hundred Day Reforms so that by the end of the unit they can trace the evolution of the modernization process between 1860 and 2000. Two worksheets are provided to guide students through the analysis of the documents below: Document Analysis Worksheet I, which should be completed separately for Documents B through E, emphasizes sourcing, close reading, and contextualizing. Close reading at this point should focus on comprehension of the information in each document. Students should read critically to identify points where they need additional information to understand the document. They CHINESE HISTORY THROUGH CHINESE EYES — The Struggle for Modernization: Lesson 2 then practice contextualization by looking for that information in the textbook and the outline of Chinese history provided in the preceding Contextualization lesson. Document Analysis Worksheet II is designed to compile information from Documents A through E. It emphasizes close reading and corroborating. At this point close reading should focus on information in Documents A through E that reveals the goals of the 1898 Hundred Day Reforms. Such information should be recorded on the chart. Questions 1 and 2 below the chart on Document Analysis Worksheet II require students to corroborate information from Documents A through E. Question 3 requires students to read Documents F and G, which are secondary sources that provide interpretations that historians have made of documents similar to those the students have just analyzed. Students should read these professional interpretations only after they have drawn some conclusions of their own by answering Questions 1 and 2. Answer keys are provided for all worksheets. To prepare students for the essay at the end of the unit, ask them to compare the leadership, goals, and outcome of the 1898 Hundred Day Reforms with those of the Self-strengthening Movement. How has the effort to modernize evolved from one effort to the next? See the file “1 Introduction to the Unit” for information on the spelling of Chinese names and other ways in which the student documents have been edited. The four Reading Like a Historian skills require students to think in ways that are probably new for them in history classes. Teachers should not be discouraged by student resistance to these higher expectations, and teachers should not be surprised if even at the end of the unit students continue to require support and encouragement to practice the skills. However, if teachers and students are diligent about following the procedures outlined in this series of lessons, by the end of the unit they should make substantial progress in internalizing these important historical thinking skills. CHINESE HISTORY THROUGH CHINESE EYES — The Struggle for Modernization: Lesson 2 Document A: The main actors in the 1898 Hundred Day Reforms THE GUANG XU EMPEROR KANG YOUWEI (guang shu) Empress Dowager Ci Xi made him emperor in 1875 when he was 4 years old. He began performing the emperor’s duties in 1889. (kang yo-way) Raised in a scholarly family, he became an advocate of modernization and gained the confidence of the Guang Xu emperor. EMPRESS DOWAGER CI XI (ts she) GENERAL RONGLU (rong lu) A Manchu general whose support enabled Empress Dowager Ci Xi to smash the 1898 Hundred Day Reforms Movement. After seizing power in a coup in 1861 when her 6-year-old son became emperor, she maintained authority until she died in 1908. Sources: Photos: Wikimedia Commons (http://commons.wikimedia.org). Text: Immanuel C. Y. Hsü, The Rise of Modern China (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000). CHINESE HISTORY THROUGH CHINESE EYES — The Struggle for Modernization: Lesson 2 Document B: Reformer Kang Youwei’s first audience with the Guang Xu emperor, June 16, 1898 (modified) After answering the emperor’s enquiries about my age and background, I said, “The foreigners are pressing upon us from all sides with the intention of partitioning our empire. The collapse and fall of China appear to be imminent.” The emperor said: “This is all brought about by the conservatives.” I said: “Your majesty’s intelligence has fathomed the cause of the malady. … unless we change all the old institutions and modernize them we cannot strengthen ourselves. … It is like a large building which, because its timbers have decayed, is about to collapse. If small patches are made to cover up the cracks, then as soon as there is a storm the building will collapse. It is therefore necessary to dismantle the building and to build anew if we want something strong and dependable. … I continued: “During the past several decades, when the ministers spoke of reforming the institutions, most of them had in mind only partial changes … When we speak of reforms we should start with the change of the institutions and the laws. Only then can they be called ‘institutional’ reforms. … I believe that the creation of a Bureau of Institutions first, to plan the change of the laws, would be of value.” … The emperor turned his eyes to the view outside his window curtains and sighed: “But what about obstructions?” I realized that the emperor was hampered in every way by the empress dowager so that he had no freedom of action, so I said, “There are still reforms which can be carried out with what powers your majesty now possesses. Today there are large numbers of high officials but there are none on whom we can depend to carry out the reforms. At present the high ministers are old and conservative … This is all due to the fact that they attained high positions by the system of ‘eight-legged’* essays. Those who learn the writing of ‘eight-legged’ essays do not read any books published after the Qin and Han periods [nearly 2,000 years before] and they do not study the affairs of the other countries of the world … The education and training they acquired in their youth did not prepare them for such tasks as the establishment of modern schools or the conduct of commerce … the only way is to employ officials of low ranks by broadening the channels for their advancement, CHINESE HISTORY THROUGH CHINESE EYES — The Struggle for Modernization: Lesson 2 granting them audiences, and hearing their views. You should select them personally for promotion. … Then the emperor asked: “At present, we suffer from poverty. How can we raise funds?” I therefore spoke briefly of the system of banking in Japan by the issuance of paper currency and of the land tax in India. … I spoke briefly of railways. “There are mineral deposits everywhere in China, more than in other countries. If we raise a big sum of several hundred million taels, we can build a nationwide system of railways, train a citizen army of a million men, purchase a hundred ironclad warships, establish schools of all types in the provinces and districts, and build naval academies and shipyards.” … I spoke of the translation of books, the sending of students abroad, the dispatch of official missions on tours of foreign countries, and other things. Source: Kang Youwei’s account of the 1898 reform movement, written in early 1899 during his exile in Japan. Translated and published in K’ang Yu-wei: A Biography and a Symposium, edited by Jung-pang Lo (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1967, pages 93-98). *For a description of the eight-legged essay, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eightlegged_essay. Document C: One of reformer Kang Youwei’s appeals to the Guang Xu emperor during the summer of 1898 (original) Both Europe and Japan owe their strength to the convocation of parliament and the adoption of constitutional government. … I beg Your Majesty to announce in an official decree to the empire that constitutional government is to be adopted and that a date for convening parliament has been set. … I [further] beg Your Majesty, as of now, before the convening of parliament, first, to assemble talented persons of the realm and to discuss with them the details of the [projected] political system; and, second, to listen to the opinions of the people of the empire and to permit them to submit in writing their views [concerning national affairs]. Source: Quoted in A Modern China and a New World: K’ang Yu-wei, Reformer and Utopian, 1858-1927, written by Kung-chuan Hsiao (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1975, page 204). CHINESE HISTORY THROUGH CHINESE EYES — The Struggle for Modernization: Lesson 2 Document D: September 12, 1898, decree by the Guang Xu emperor concerning reform of the imperial government (original) In revitalizing the various administrative departments our government adopts Western methods and principles. For, in a true sense, there is no difference between China and the West in setting up government for the sake of the people. Since, however, Westerners have studied [the science of government] more diligently than we, their findings can be used to supplement our deficiencies. Scholars and officials today whose purview does not go beyond China [regard Westerners] as practically devoid of precepts or principles. They do not know that the science of government as it exists in Western countries has very rich and varied contents, and that its chief aim is to develop the people’s knowledge and intelligence and to make their living commodious. The best part of that science is capable of bringing about improvements in human nature and the prolongation of human life. Source: Quoted in The Rise of Modern China (6th ed.), written by Immanuel C. Y. Hsü (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000, pages 374-375). CHINESE HISTORY THROUGH CHINESE EYES — The Struggle for Modernization: Lesson 2 Document E: Reform decrees issued by the Guang Xu emperor (modified) Between June 11 and September 20, 1989, the emperor issued forty to fifty reform decrees, including: June 11 Establishment of an Imperial University at Beijing (now called Beijing University). June 12 Tour of foreign countries by high officials June 12 Protection of foreign missionaries. June 23 Replacement of the eight-legged essay in the civil service examinations by essays on current affairs. June 25 Promotion of railway construction. June 26 Improvement in administrative efficiency by eliminating delays and by developing a new, simplified administrative procedure. June 20 Promotion of agricultural, industrial, and commercial developments. July 5 Encouragement of invention. July 10 Establishment of modern schools in the provinces devoted to the pursuit of both Chinese and Western studies, including colleges, high schools, and elementary schools. July 29 Improvement and simplification of legal codes. Aug. 6 Establishment of a school for the overseas subjects. Aug. 30 Abolition of unnecessary government offices, including the Supervisory of Imperial Instruction, the Office of Transmission, the Banqueting Court, the Court of State Ceremonial, the Imperial Stud, the Court of Sacrificial Worship, and the Court of Judicature and Revision. Sept. 5 Appointment of reformers to government posts. Sept. 11 Encouragement of suggestions from private citizens, to be forwarded by government offices on the day they are received. Source: Historian Immanuel C. Y. Hsü, writing in The Rise of Modern China (6th ed.), published in 2000 by Oxford University Press (p. 375-376). CHINESE HISTORY THROUGH CHINESE EYES — The Struggle for Modernization: Lesson 2 Document F: The empress dowager smashes the Hundred Day Reforms (original) The struggle between the reformists and their opposition was very acute. Three days after the [June 11] reform edict was issued, Empress Dowager Ci Xi … appointed her trusted follower Ronglu as Viceroy of Zhili and Supreme Commander of the Beiyang Army. In this way she took control over both Beijing and Tianjin, and awaited the opportunity to destroy the reform movement. In early September, the two cities were full of rumors that Ci Xi and Ronglu were conspiring to coerce the emperor to abdicate during a military review in Tianjin. Sensing the gravity of the situation, Emperor Guang Xu secretly instructed Kang Youwei and his group to devise plans against the conspiracy. As the reformists did not rely on the masses, they had no real strength. And at this critical juncture, they thought they could rely on Yuan Shikai’s army, kill Ronglu during the military review, and avert the crisis. … When Tan Sitong paid him [Yuan Shikai] a secret visit he was very eloquent in his support, but after the visit he immediately informed Ronglu about the secrets of the reformists. On September 21, Empress Dowager Ci Xi staged a coup d’état, imprisoned Emperor Guang Xu and arrested the reformist leaders. The reform movement ended in defeat. After the coup d’état, Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao escaped abroad with the help of Britain and Japan. … At the end of September, Tan Sitong, Liu Guangdi, Yang Rui, Lin Xu, Yang Shenxiu and Kang Guangren (Kang Youwei’s brother) were executed, and the officials who had supported the reform were dismissed. All of the new policies were abolished, except the establishment of a Metropolitan College [now called Beijing University]. Source: Historian Bai Shouyi, writing in An Outline History of China, published in 2008 by the Foreign Language Press in Beijing (p. 432-433). CHINESE HISTORY THROUGH CHINESE EYES — The Struggle for Modernization: Lesson 2 Document G: An assessment of the Hundred Day Reforms (original) Among the principal causes for the failure of the reform were the inexperience of the reformers and their ill-considered strategy, the reluctance of the empress dowager to give up power, and the powerful conservative opposition. … In 1898 Kang Youwei was only forty and his chief supporter Liang Qichao twenty-five, both without previous experience in government service. Neither had been abroad before the reform, and neither had more than a superficial understanding of Western culture and institutions. Their knowledge of the West was limited to what they read in the missionary publications and what they observed in the colonial administrations in Hong Kong and Shanghai. … [Kang] was able to win over the emperor as the legal source of power, but he ignored the obvious fact that the real power of state rested with the dowager. Impatient to achieve quick results, he hardly considered the effects of the reform decrees on others. … Little did he realize that the radical reform was in effect a war on the whole Confucian state and society, one which could not but arouse strong opposition from many quarters. The repercussions of the failure of 1898 were many and far-reaching. First, it proved that progressive reform from the top down was impossible. Secondly, under the empress dowager and die-hard conservatives who had returned to power, the court was totally incapable of leadership. … Thirdly, an increasing number of the Chinese came to feel that their future lay in the complete overthrow of the Manchu dynasty, and that such an occurrence could not be realized by peaceful change; only a bloody revolution from below could effect it. Dr. Sun Yat-sen took the lead in promoting this approach. Source: The Rise of Modern China (6th ed.), written by Immanuel C. Y. Hsü. Published in 2000 by Oxford University Press; p. 380-381, 383-384. CHINESE HISTORY THROUGH CHINESE EYES — The Struggle for Modernization: Lesson 2 Sources Bai, Shouyi. (2008). An Outline History of China. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. Document F: Pages 432-433. Hsiao, Kung-Chuan. (1975). A Modern China and a New World: K’ang Yu-Wei, Reformer and Utopian, 1858-1927. Seattle: University of Washington Press. Document C: Pages 204. Hsü, Immanuel C. Y. (2000). The Rise of Modern China (6th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. Document D: Pages 374-375. Document E: Pages 375-376. Document G: Pages 380-381, 383-384. Lo, Jung-Pang (Ed. and Trans.). (1967). K’ang Yu-Wei: A Biography and a Symposium. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. Document B: Pages 93-98. CHINESE HISTORY THROUGH CHINESE EYES — The Struggle for Modernization: Lesson 2