Don`t blame Columbus for all of the Indians problems - Mr. Lamb

advertisement

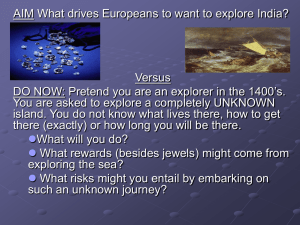

Don't Blame Columbus for All the Indians' Ills The New York Times By JOHN NOBLE WILFORD Published: October 29, 2002 Europeans first came to the Western Hemisphere armed with guns, the cross and, unknowingly, pathogens. Against the alien agents of disease, the indigenous people never had a chance. Their immune systems were unprepared to fight smallpox and measles, malaria and yellow fever. The epidemics that resulted have been well documented. What had not been clearly recognized until now, though, is that the general health of Native Americans had apparently been deteriorating for centuries before 1492. That is the conclusion of a team of anthropologists, economists and paleopathologists who have completed a wide-ranging study of the health of people living in the Western Hemisphere in the last 7,000 years. The researchers, whose work is regarded as the most comprehensive yet, say their findings in no way diminish the dreadful impact Old World diseases had on the people of the New World. But it suggests that the New World was hardly a healthful Eden. More than 12,500 skeletons from 65 sites in North and South America -slightly more than half of them from pre-Columbians -- were analyzed for evidence of infections, malnutrition and other health problems in various social and geographical settings. The researchers used standardized criteria to rate the incidence and degree of these health factors by time and geography. Some trends leapt out from the resulting index. The healthiest sites for Native Americans were typically the oldest sites, predating Columbus by more than 1,000 years. Then came a marked decline. ''Our research shows that health was on a downward trajectory long before Columbus arrived,'' Dr. Richard H. Steckel and Dr. Jerome C. Rose, study leaders, wrote in ''The Backbone of History: Health and Nutrition in the Western Hemisphere,'' a book they edited. It was published in August. Dr. Steckel, an economist and anthropologist at Ohio State University, and Dr. Rose, an anthropologist at the University of Arkansas, stressed in interviews that their findings in no way mitigated the responsibility of Europeans as bearers of disease devastating to native societies. Yet the research, they said, should correct a widely held misperception that the New World was virtually free of disease before 1492. In an epilogue to the book, Dr. Philip D. Curtin, an emeritus professor of history at Johns Hopkins University, said the skeletal evidence of the physical well-being of pre-Columbians ''shows conclusively that however much it may have deteriorated on contact with the outer world, it was far from paradisiacal before the Europeans and Africans arrived.'' About 50 scientists and scholars joined in the research and contributed chapters to the book. One of them, Dr. George J. Armelagos of Emory University, a pioneer in the field of paleopathology, said in an interview that the research provided an ''evolutionary history of disease in the New World.'' The surprise, Dr. Armelagos said, was not the evidence of many infectious diseases, but that the pre-Columbians were not better nourished and in general healthier. Others said the research, supported by the National Science Foundation and Ohio State, would be the talk of scholarly seminars for years to come and the foundation for more detailed investigations of pre-Columbian health. Dr. Steckel is considering conducting a similar study of health patterns well into European prehistory. ''Although some of the authors occasionally appear to overstate the strength of the case they can make, they are also careful to indicate the limitations of the evidence,'' Dr. Curtin wrote of the Steckel-Rose research. ''They recognize that skeletal material is the best comparative evidence we have for the human condition over such a long period of time, but it is not perfect.'' The research team gathered evidence on seven basic indicators of chronic physical conditions that can be detected in skeletons -- namely, degenerative joint disease, dental health, stature, anemia, arrested tissue development, infections and trauma from injuries. Dr. Steckel and Dr. Rose called this ''by far the largest comparable data set of this type ever created.'' The researchers attributed the widespread decline in health in large part to the rise of agriculture and urban living. People in South and Central America began domesticating crops more than 5,000 years ago, and the rise of cities there began more than 2,000 years ago. These were mixed blessings. Farming tended to limit the diversity of diets, and the congestion of towns and cities contributed to the rapid spread of disease. In the widening inequalities of urban societies, hard work on lowprotein diets left most people vulnerable to illness and early death. Similar signs of deleterious health effects have been found in the ancient Middle East, where agriculture started some 10,000 years ago. But the health consequences of farming and urbanism, Dr. Rose said, appeared to have been more abrupt in the New World. The more mobile, less densely settled populations were usually the healthiest pre-Columbians. They were taller and had fewer signs of infectious lesions in their bones than residents of large settlements. Their diet was sufficiently rich and varied, the researchers said, for them to largely avoid the symptoms of childhood deprivation, like stunting and anemia. Even so, in the simplest hunter-gatherer societies, few people survived past age 50. In the healthiest cultures in the 1,000 years before Columbus, a life span of no more than 35 years might be usual. In examining the skeletal evidence, paleopathologists rated the healthiest pre-Columbians to be people living 1,200 years ago on the coast of Brazil, where they had access to ample food from land and sea. Their relative isolation protected them from most infectious diseases. Conditions also must have been salubrious along the coasts of South Carolina and Southern California, as well as among the farming and hunting societies in what is now the Midwest. Indian groups occupied the top 14 spots of the health index, and 11 of these sites predate the arrival of Europeans. The least healthy people in the study were from the urban cultures of Mexico and Central America, notably where the Maya civilization flourished presumably at great cost to life and limb, and the Zuni of New Mexico. The Zuni lived at a 400-year-old site, Hawikku, a crowded, drought-prone farming pueblo that presumably met its demise before European settlers made contact. It was their hard lot, Dr. Rose said, to be farmers ''on the boundaries of sustainable environments.'' ''Pre-Columbian populations were among the healthiest and the least healthy in our sample,'' Dr. Steckel and Dr. Rose said. ''While preColumbian natives may have lived in a disease environment substantially different from that in other parts of the globe, the original inhabitants also brought with them, or evolved with, enough pathogens to create chronic conditions of ill health under conditions of systematic agriculture and urban living.'' In recent examinations of 1,000-year-old Peruvian mummies, for example, paleopathologists discovered clear traces of tuberculosis in their lungs, more evidence that native Americans might already have been infected with some of the diseases that were thought to have been brought to the New World by European explorers. Tuberculosis bears another message: as an opportunistic disease, it strikes when times are tough, often overwhelming the bodies of people already weakened by malnutrition, poor sanitation in urban centers and debilitated immune systems. The Steckel-Rose research extended the survey to the health consequences of the first contacts with American Indians by Europeans and Africans and the health of European-Americans and African-Americans up to the early 20th century. Not surprisingly, African-American slaves were near the bottom of the health index. An examination of plantation slaves buried in South Carolina, Dr. Steckel said, revealed that their poor health compared to that of ''preColumbian Indian populations threatened with extinction.'' On the other hand, blacks buried at Philadelphia's African Church in the 1800's were in the top half of the health index. Their general conditions were apparently superior to those of small-town, middle-class whites, Dr. Steckel said. The researchers found one exception to the rule that the healthiest sites for Native Americans were the oldest sites. Equestrian nomads of the Great Plains of North America in the 19th century seemed to enjoy excellent health, near the top of the index. They were not fenced in to farms or cities. In a concluding chapter of their book, Dr. Steckel and Dr. Rose said the study showed that ''the health decline was precipitous with the changes in ecological environments where people lived.'' It is not a new idea in anthropology, they conceded, ''but scholars in general have yet to absorb it.'' Photos: Signs of anemia can be seen in the eye orbit and in the pits on top of the skull. (Jerome Rose)(pg. F1); Ancient Indian forearm bones, top left, show swelling from infection in the area of a break.; Above, severe degenerative disease is evident in a middle-aged man's knee joint.; At left, healthy and diseased adult femurs. Chronic infection or osteomyelitis is seen in the lower one.; Indian health was deteriorating before Columbus arrived. At left, lipping vertebrae edges show arthritis in an older man's spine. At right, a molar destroyed by dental decay and another one being destroyed in an adult. (Photographs by Jerome Rose)(pg. F6)