Museum Participation in Collaborative Digital

advertisement

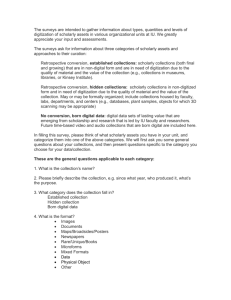

MUSEUM PARTICIPATION IN COLLABORATIVE DIGITAL PROJECTS: A STUDY OF PERCEPTIONS OF STAFF MEMBERS AT CONNECTICUT HERITAGE ORGANIZATIONS BY ELIZABETH ROSE A Special Project Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Library Science Southern Connecticut State University New Haven, Connecticut April 2014 ABSTRACT Author: Title: Elizabeth Rose MUSEUM PARTICIPATION IN COLLABORATIVE DIGITAL PROJECTS: A STUDY OF PERCEPTIONS OF STAFF MEMBERS AT CONNECTICUT HERITAGE ORGANIZATIONS Special Project Advisor: Mary E. Brown, Ph.D. Institution: Southern Connecticut State University Year: 2014 In order to understand the problem of smaller heritage organizations’ participation in collaborative digital projects in Connecticut, this research study used an online survey of staff from selected organizations in the state to learn how they perceive the benefits and barriers to their organizations’ involvement. The survey found that while all the responding organizations were engaged in some digitization of their materials, they faced some significant barriers and would like to do more in order to reach a broader audience. Funding for additional staff time to work on digitization was the most desired type of support. Additionally, the study addressed one significant barrier – lack of a common set of metadata standards – by surveying the practices of successful state digitization projects to develop recommendations about what metadata standards would be most appropriate for these organizations’ collections. Modified Dublin Core was found to be the most accessible and flexible metadata standard to use for such collaborative digital projects. These findings were shared with the Connecticut League of History Organizations and Connecticut History Online in order to help inform their plans for shaping collaborative digital projects in the state. Keywords: digitization, cultural heritage, collaboration, museums, metadata MUSEUM PARTICIPATION IN COLLABORATIVE DIGITAL PROJECTS: A STUDY OF PERCEPTIONS OF STAFF MEMBERS AT CONNECTICUT HERITAGE ORGANIZATIONS BY ELIZABETH ROSE This special project proposal was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s Special Project advisor, Dr. Mary Brown, and it has been approved by the members of the candidate’s special project committee. It was submitted to the School of Graduate Studies and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Library Science. ______________________________ Mary E. Brown, Ph.D. Special Project Advisor _____________________________ Briann Greenfield, Ph.D. Second Reader I. INTRODUCTION Overview Since the late 1990s, libraries, museums, and archives across the United States have created collaborative digital collections to share cultural heritage objects from their collections with a larger public. The new Digital Public Library of America has identified 40 such collaborative digital projects across the country and is currently working with six of them as “content hubs” to contribute material as part of a pilot phase (“Hubs,” 2013). Smaller museums, libraries, and historical organizations (hereafter referred to collectively as heritage organizations) face a number of barriers to participating in collaborative digital projects. These barriers include limited staff, limited funding, lack of expertise in digitization and cataloging/metadata standards, and lack of equipment for digitization. In some organizations, collections may not have been catalogued at all, or have been catalogued according to the organization’s internal needs rather than adhering to any broader standard for access or preservation. When such barriers prevent small heritage organizations from participating, the digital projects that are developed are missing the richness of these organizations’ collections, and the organizations themselves miss out on reaching out to a growing audience that looks for cultural content online. In Connecticut, several collaborative digital projects are currently underway. Connecticut History Online has been gathering images and other materials since 1999, and will serve as a collection point for material dealing with Connecticut history for the new Connecticut Digital Archive, which in turn will send content to the Digital Public Library of America (“Connecticut Digital Archive Launches Softly,” 2013). Other digital projects include the Treasures of Connecticut Libraries, which collected digital images from public libraries and historical societies in the state, and Connecticut Archives Online, which collects archival finding aids from different archives in the state so that researchers can more easily locate material. To date, these projects have mainly represented Connecticut’s larger heritage organizations. Connecticut History Online, for instance, includes content from seven organizations, with the majority of its content coming from four large repositories (“About Connecticut History Online,” 2012). Most of Connecticut Archives Online’s content comes from university collections and from the Connecticut State Library, with only three local historical societies represented (“What is CAO,” n.d.). In order to understand the problem of smaller heritage organizations’ participation in collaborative digital projects in Connecticut, this research study used an online survey of staff from selected organizations in the state to learn how they perceive the benefits and barriers to their organizations’ involvement. The survey and request to participate was distributed via email to participants in the “Digital Collections 101” workshop sponsored by the Connecticut League of History Organizations and the Conservation ConneCTion initiative in May 2013, and to selected organizations in Connecticut using the PastPerfect museum software. Questions about the nature of the organization’s collections and current cataloging practices helped establish the context for the perceptions of benefits and barriers. A supplemental part of the study addressed metadata – one potential barrier to collaborative digitization projects – by surveying the existing literature and gathering information from other state project staff (including interviews) to determine the best approach to metadata for statewide projects in Connecticut. Significance and Relevance The problem of smaller organizations’ exclusion from collaborative digital projects is twofold: first, that the digital collections that result do not represent the full richness and diversity of the state’s cultural heritage, and second, that smaller organizations miss out on the benefits of sharing their collections with a broader public online. If only larger organizations’ collections are represented, digital collections will reflect the biases of those organizations’ collecting history and leave out the geographic regions, ethnic groups, and topics that are represented in smaller organizations’ collections, which are typically closely tied to local history and specialized topics. For instance, Hungarians were a significant ethnic group in the area around Bridgeport. But a search of Connecticut History Online produces only three results for the term “Hungarian,” and two of these are only minimally relevant (“Connecticut History Online,” 2012). As more users – including students and teachers – look online for material in coming years, organizations that do not participate in digital projects risk losing their audience. They may also miss opportunities to collaborate with each other on shared collection themes and material, which may be discovered through such projects. Understanding and addressing the barriers that prevent participation in these collaborative digital projects is important in order to ensure that Connecticut’s cultural heritage is broadly represented, made accessible to audiences who increasingly look for content online, and preserved. While digital projects in Connecticut have had limited participation from smaller organizations, similar projects in some other states have included a much wider range of organizations. In each of these cases, projects took deliberate steps to encourage broader participation, including addressing the specific barriers that faced smaller organizations. As the Connecticut Digital Archive prepares to start taking in new content from other organizations in 2014, it is an opportune time to determine perceptions of the benefits and obstacles to participation, in order to help decision makers proceed with the best chances of broad-based participation in the future. This study addresses the problem of barriers to smaller organizations’ participation in collaborative digital projects in two ways. First, it assesses the perceived benefits and barriers to participating in collaborative digital projects by surveying staff from selected heritage organizations in Connecticut. Background research from evaluations of digital projects in other states helped shape the survey questions, testing possible ways that these projects might be made more accessible. Second, the study addresses one specific barrier – lack of a common set of metadata standards – by making recommendations about what metadata standards are most appropriate for these organizations’ collections. These recommendations will be based both on survey questions about cataloging practices and on gathering information on best practices being used by other collaborative projects around the country. This study contributes both to the cultural heritage community in Connecticut (represented by the client organization, the Connecticut League of History Organizations) and to those in library and information science and digital humanities fields concerned with making museum and archival collections available to the public. It identifies barriers to the participation of smaller heritage organizations in the collaborative digital projects that are underway in Connecticut, and determine some steps by which these barriers might be overcome. Studying metadata practices helps identify the best approach to helping smaller organizations catalog their collections in a way that will ensure they can be shared across the state. Review of Literature Libraries, museums, and archives across the country have created collaborative digital collections to share cultural heritage objects from their collections with a larger public, and these are becoming an important way for users to discover material. It is important that smaller museums and organizations are able to participate in these projects, which have “tended to originate in the largest, most well-funded institutions” (Jones, 2005, p. 205). Evaluation literature on specific digital projects, on collaboration among these different kinds of institutions, and on metadata approaches points to common problems of participation by smaller museums, and some possible solutions. Evaluations and descriptions of state and regional collaborative digital projects help to identify specific barriers to participation by smaller institutions. These include lack of staff time and capacity (including knowledge about digitization and metadata for collection materials), lack of funding, lack of technological capacity (access to equipment, familiarity with digitization standards), and lack of understanding of the importance of digitizing materials, as well as concerns about copyright issues in sharing materials. Wisser (2005) reports that the North Carolina ECHO project found that “the diversity of the cultural heritage landscape, with its wide range of technological and professional knowledge and capabilities, produces challenges for a statewide consortium” (p. 165). A survey of cultural organizations in the state showed that the majority of institutions had five or fewer staff members, and many institutions reported limitations related to staffing, infrastructure, and physical space (Wisser, 2005). Similarly, institutions in Michigan indicated that access to equipment and training in digitization techniques and standards were high priority needs, closely followed by training in copyright issues, metadata creation, and storage for master copies of digital items (Jones, 2005). Evaluations of other statewide projects also highlight the strategic steps that these projects took to encourage widespread participation by heritage organizations. These include dedicated outreach staff for the Maine Memory Network who trained staff at all 270 contributing organizations, helped them select material to include through workshops, video presentations on "Doing Good History," and individual consultation. They found that this kind of "handholding" was important in encouraging broad-based participation (Mt. Auburn Associates, Inc., 2003; Amoroso, 2014). The New Jersey Digital Highway developed software tools to make it easier for staff at heritage organizations to upload and describe their materials, while Ohio Memory Online staff provided guidance to organizations about what kinds of materials would be most valuable to the statewide project ( Gemmill & O’Neal, 2005; Jeng, 2008). The Columbia River Basin Ethnic History Archive provided a travelling team to handle the digitization of materials (Wykoff, Mercier, Bond, & Cornish, 2005). In the Making of Modern Michigan project, a preliminary survey had shown that libraries were reluctant to send their rare material to a centralized location for digitizing, fearing that they would not get it back in a timely fashion. In response, the project identified “digitization centers” across the state that could dedicate a scanner to the project, and determined that 95% of the state’s libraries were located within a two-hour drive of one of these centers. Grants of $1500 provided an important incentive for small libraries to participate, enabling them to purchase their own scanner, pay a staff member for the extra time to do the scanning and metadata creation or to pay replacement staff for the library (Jones, 2014). Grants to heritage organizations also played an important role in encouraging participation in the Maine Memory Network - where they were used to encourage partnerships among a community's schools, libraries, and heritage organizations - and the North Carolina ECHO projects (Amoroso, 2014; Wisser, 2014). A particular challenge for a number of projects bringing together different types of heritage organizations is the need for a common set of descriptors for the material they contribute. Creation of consistent, quality metadata is essential to the operation of both digital collections and online catalogs, making possible effective retrieval of information by users. Although library science professionals are keenly aware of the importance of quality metadata, Park and Tosaka (2010) found that metadata guidelines and other quality control measures were used less often in collaborative projects involving multiple institutions than in those of a single institution. Libraries, archives, and museums have disparate “metadata cultures and practices” that stem from different traditions of sharing information about their collections (Roel, 2013). Libraries and archives have long experience with providing collection information to the public and encouraging direct public access to resources. Librarians are trained to use highly standardized cataloging methods in order to share information across institutions, employing detailed controlled vocabularies. Archivists have built on this tradition in recent years by making finding aids available electronically and developing descriptive standards for archival collections. Museums, on the other hand, emphasize presenting their unique collections to the public in welldesigned exhibitions, rather than sharing collections information directly with the public, and have not developed a system for sharing information across institutions. Information about collections is held in “collection management systems” which are meant for internal staff use and employ the institution’s own methods for cataloging information (Bishoff, 2004; Nodler & Botticelli, 2009; Wythe, 2006). These systems tend to use proprietary software, making it more difficult to share information (Waibel, 2010). In other statewide digitization projects, small organizations often had trouble providing good descriptive metadata, as they did not have the staff capacity to do much cataloging. This was one of the major reasons given for the Maine Memory Project’s lower than expected number of items contributed at the time of the project evaluation. Smaller organizations found that cataloging was the most time-consuming element of the process, and many items that had been scanned had not yet been uploaded because of the lack of documentation to meet the project’s high standards for cataloging (Mt. Auburn Associates, Inc., 2003, p. 27). Anticipating this problem in the Making of Modern Michigan project, much effort went into creating a userfriendly process for metadata creation (Jones, 2005, p. 219). The North Carolina ECHO project focused particularly on helping partner institutions create good metadata, offering onsite training, an online template for metadata creation, and consultations with a metadata coordinator (Wisser, 2005) as part of an overall focus on empowering local organizations to carry out their own digitization projects. Different solutions have been found for creating metadata combining different cataloging traditions. The Morgan Library in New York chose to use a library system to catalog all their materials (including works of art as well as rare books and typical library collections), adapting MARC/AACR standards to encompass the needs of curators. Connecticut History Online followed this model in its first phase, until a shift in software systems required a change (Foulke, 2014). A more common solution is to use the most basic type of metadata – the Dublin Core – as a lowest common denominator. Dublin Core consists of 15 elements that can be used for description of a range of resources (CDP Metadata Working Group, 2006; “Dublin Core Metadata Element Set, Version 1.1,” 2013), and it has been refined and adapted in slightly different ways for many different digital heritage projects. Yet another approach is to allow a range of metadata schemas and ensure interoperability through data exchange protocols. For instance, the “Music of Social Change” project in Atlanta used the Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH) to maximize flexibility for participating institutions. This protocol can handle any metadata format expressed by XML, including those that are significantly more structured than Dublin Core. It is therefore “maximally forgiving of discordant metadata suppliers,” giving institutions discretion as to what metadata are exposed and what level of description is provided (Roel, 2013). Most of the cultural heritage digital projects represented in the literature have adopted Dublin Core as a metadata standard, though a number of projects have made modifications in order to make it easier for organizations with limited staff to contribute. For instance, projects in Alabama and Colorado required only a subset of Dublin Core’s 15 elements (Downer, Medina, Nicol, & Trehub, 2005; Bishoff, 2000). Collaboration among different types of heritage organizations has been spurred by the potential benefits of bringing together collections digitally and building audience, as well as by funding opportunities that prioritize digital collaboration, such as grants from the Institute for Library and Museum Services. In some cases collaboration has been encouraged by a desire to increase place-based heritage tourism. For instance, five cultural institutions in Newport, Rhode Island that are located close to each other and share common collections are creating a joint online collections catalog known as NewPortal (Bernier, Costa, Ecenarro, & Keagle, 2013). In Nova Scotia, more than 50 museums collaborated on a joint catalog known as NovaMuse (“NovaMuse: About,” 2013). The literature on collaboration between museums, libraries, and archives points to the challenges as well as the benefits of these collaborative projects. Collaborative digital projects have the potential to integrate heritage organizations and unite collections in the digital world. Given & McTavish (2010) suggest that such projects are bringing about a convergence of libraries, archives, and museums, reflecting a return to the common historical roots of these institutions. Evaluations of state and regional digital collections projects highlight the importance of taking deliberate steps to maximize the involvement of smaller institutions in such projects, and of understanding the challenges that they face in digitizing and cataloging their collections. Focusing on metadata – one of the key technical challenges of bringing together a variety of large and small institutions in such projects – helps to highlight some of the concrete steps that might need to be taken. The current research project contributes to this literature by documenting the perceptions of staff at smaller heritage organizations in Connecticut, where digitization projects have been built but have not yet involved a large number of organizations. While other studies have explored challenges and barriers in the context of describing or evaluating projects in other states, none have focused on organizations in Connecticut, and none have focused specifically on the problem of encouraging the participation of smaller heritage organizations. II. RESEARCH METHODS The study used an online survey of staff from selected Connecticut heritage organizations to identify their perceptions about the benefits and barriers to participating in collaborative digital projects. A supplemental part of the study on metadata standards surveyed the research literature to identify five state or regional digital collections projects with broad participation (i.e., more than 15 organizations contributing content). Using this literature, interviews with project staff, and documentation available on the project’s websites, the study analyzes the metadata approaches taken by these projects. Subjects The survey and request to participate was distributed to staff at heritage organizations in Connecticut who are responsible for historical collections (of papers, photographs, artwork, clothing, and other three-dimensional objects). Subjects could be paid professional staff or volunteers, including board members. See Appendix 1 for cover letters that accompanied invitations to participate in the survey. Subjects were recruited through three different email invitations: first, an invitation was sent to all 30 participants in a digitization workshop sponsored by the Conservation ConneCTion initiative in May 2013 in conjunction with the Connecticut League of History Organizations (“Digital Collections 101: An Introductory Workshop,” 2013). Participants at this workshop were staff and board members from heritage organizations who were interested in learning more about digital collections. Second, an invitation was sent to the organizations listed as being users of the PastPerfect museum software in Connecticut (“Past Perfect Client List,” 2013) but not represented in the digitization workshop list. Since using Past Perfect reflects a commitment to computerized collections cataloging (and potentially online presentation of collections), this helped to recruit respondents whose organizations have an interest in digital projects and the capacity to share cataloging information. Finally, the Connecticut League of History Organizations sent an email out to its members, inviting them to participate in the survey. Instruments The survey, consisting of 14 multiple-choice questions, is designed to be relatively easy to complete while still producing valuable information. The questions are independent of each other and start with the easiest-to-answer questions, such as the type of organization, the respondent’s role, and what kind of staffing arrangement is in place for managing collections. The organization's name is not requested, providing anonymity for respondents. Five questions about collection management and current digitization practices measure how prepared the organization is to contribute material to a collaborative project. Two of these questions allow for a write-in response if the fixed-choice responses are not adequate. A table asks respondents about their level of familiarity with four different digital projects in Connecticut: Connecticut History Online, Connecticut Archives Online, Treasures of Connecticut Libraries, and the Connecticut Digital Archive. The final four questions ask about the benefits and barriers to participating in collaborative digital projects, the organization’s current sharing of digital images, and the type of support that would be most valuable for the organization to participate in digitization projects. See Appendix 2 for the survey. Procedure The survey was posted online using Google Forms, and invitations to participants included the URL and instructions. There were 44 total respondents. Data entered into the Google Form populated a spreadsheet in Google Drive. Once the responses were submitted, the raw data were reviewed and re-entered into a second Excel spreadsheet; one duplicate response was removed and write-in answers were assigned to categories when appropriate, in order to create cleaner data for analysis. Partway through the administration of the survey, a problem with the formatting one of the questions required revision in order to allow respondents to select more than one response, so the initial responses to that particular question had to be discarded. Responses were analyzed in terms of percentages and frequency, as well as looking at relationships between staffing levels of organizations and attitudes about participating in digital projects. For the analysis of metadata in other digital collections projects, the study used the research literature on state and regional projects to identify five projects with broad-based participation, defined as having at least 15 different organizations contributing content. These projects were the Maine Memory Project, the Making of Modern Michigan project, the New Jersey Digital Highway, the North Carolina ECHO project, and Ohio Memory Online. Connecticut History Online was also studied with this group as it is the most important such project in Connecticut, even though it does not meet the criteria of having broad-based participation. For each of these projects, metadata standards and procedures described in the literature and documentation provided on the projects’ websites were analyzed in order to show commonalities and differences in the projects’ approach, and interviews were conducted with project staff members to learn more in-depth about their evolution. III. PROJECT RESULTS A. Survey results Organizations and respondents The largest group of respondents was from local historical societies (68%), with smaller numbers representing museums (28%) and other categories (4%). Reflecting the predominance of historical societies, the respondents’ collections were described as a combination of archival materials, historical objects, and works of art. Sixteen percent described their collections as primarily archival, and 14% described theirs as primarily historical artifacts/museum objects. None described their collection as primarily paintings or other works of art. Library that includes historical collections 2% Organization Type (n=44) Museum 28% Art & local history exibition space 2% Local historical society 68% The small size of these organizations as a group is reflected by the staff they have to manage their collections. The largest category of respondents (43%) said that their organizations relied on volunteers to carry out this task, and the second largest category said that their organizations had a part-time curator or archivist. Only 7% of respondents worked for organizations that had two or more full-time staff members dedicated to managing collections, and one respondent wrote in that his/her collection had "no real management." Two or more full-time staff members 7% Staffing for Collection Management No real (n=44) Full-time curator or archivist 14% management 2% Part-time curator or archivist 34% Volunteers 43% About a quarter of the people responding to the survey were directors (or assistant directors) of the heritage organization, and some identified their role in the organization as "all of the above" (i.e., curator, archivist, director, board member or volunteer), reflecting the many hats that people in these organizations need to wear. The State of Cataloging With limited staff and volunteer time, these organizations face some significant challenges in cataloging their collections: 36% reported that less than half their collection is catalogued (i.e., that staff can find basic information for each item in either written or electronic records) and another 16% said that about half their collection is catalogued. Thirty-seven percent reported that their collection is mostly catalogued, while only 11% reported that their collection is fully catalogued. How much of the collection is catalogued? (n=44) Less than half catalogued 36% Half catalogued 16% Fully catalogued 11% Mostly catalogued 37% To catalog and manage their collections, heritage organizations can use a number of tools, and these may affect their capacity to participate in collaborative digital projects. The majority of respondents (52%) used Past Perfect, proprietary software that is designed specifically for historical collections. Seven percent used another specialized database program (The Museum System, Archon, CollectionSpace, and a library catalog). At the other end of the spectrum, a quarter (23%) used paper files or a log book rather than an electronic system. Eighteen percent of respondents fell somewhere in between, using either an Excel spreadsheet or a generic database program such as Microsoft Access or Filemaker. Collection Management Tools (n=44) Specialized database program 7% Paper files or log book 23% Past Perfect 52% Excel spreadsheet Standard 9% database (FileMaker, Access) 9% In their cataloging, respondents reported using a combination of cataloging standards and terms. When asked to identify which standards they used, the most frequent answer was that they used their own terms to describe collections, a practice that makes any kind of standardization more difficult. This pattern was especially associated with organizations whose collections were managed by volunteers; those who reported having an archivist or curator were more likely to report using a controlled vocabulary. Beyond these local terms, the two most frequently mentioned controlled vocabularies used in cataloging collections were the Library of Congress subject headings and that the Nomenclature for Museum Cataloging (also known as Chenhall’s or as the lexicon that is provided with Past Perfect, which is based on this) (“The Lexicon,” n.d.) . Standards such as Describing Archival Collections and the Art and Architecture Thesaurus were listed less frequently. Controlled Vocabularies Other 2 Nomenclature 10 Our own terms 25 Art and Architecture Thesaurus 4 Describing Archival Collections (DACS) 4 Library of Congress subject headings 10 Attitudes towards digitization The survey found overwhelmingly positive attitudes towards digitization in general. Most organizations (91%) are already digitizing items from their collections for specific purposes, such as research requests, reproduction in publications, or use in exhibitions. Thirty-two percent reported that their organization already shares a significant number of images online (through a website, Facebook, or other platform), and another 61% indicate that they think it would be beneficial for their organization to do so. Only three respondents (7%) indicated negative or skeptical attitudes towards this kind of effort, with one commenting that s/he needed to see more evidence of the benefit of doing this in order to justify the cost. Attitudes Towards Digitization (n=44) Not beneficial 5% Currently shares images from our collection online 32% Need to show benefit to justify cost 2% Beneficial but have not done it very much 61% Benefits of Sharing Collections Information Connect with other institutions Service beyond limited library hours Offer material to teachers/students Reach a broader audience 22 26 28 43 Respondents overwhelmingly identified "reaching a broader audience" as the benefit to their organization of sharing information about their collections online; all but one respondent selected this answer. They also expressed a desire to reach out to teachers and students, to make material available beyond their limited library hours, and to connect with other institutions. One respondent noted that making material available would free up some of their volunteers' valuable time, and another expressed an interest in fostering shared exhibits and adding "greater depth and insight into CT history by seeing a bigger picture of the collections in the state." Most respondents were familiar with Connecticut History Online, the digital project in Connecticut that has been the most fully developed, but only about half the respondents had heard of Connecticut Archives Online or the new Connecticut Digital Archive. Treasures of Connecticut Libraries was even less well-known; only about a third of respondents had heard of it. Barriers and Assistance Despite these positive attitudes towards digitization projects, the respondents identified significant barriers to their organizations' sharing more of their collections online. Of these, the lack of staff time to select and digitize material was mentioned most frequently. Lack of time to describe material (i.e., create metadata) and concerns about material being used without permission were the next most frequently cited concerns, with lack of equipment and lack of information about online platforms to use in sharing material being mentioned less often. Barriers Permission concerns 23 Lack of time to describe material Lack of scanning equipment 30 9 Lack of staff time to select and digitize material Don’t know the best way to share images online 42 12 One of the challenging aspects of digitization projects can be selecting which items should be digitized, based on historical importance, uniqueness, and public interest. A majority of the respondents (57%) indicated that they felt comfortable selecting which collections items were most worth digitizing, while 39% indicated that they “could use guidance in choosing which items in our collection are most worth digitizing.” Selecting Items to Digitize (n=44) Other 4% Could use guidance 39% Confident about selecting material 57% When asked what kind of help would be most likely to spur their organizations to do more with digitizing and sharing collections online, the overwhelming response was "funding for additional staff time to work on digitization." This follows logically from identifying the biggest barrier being lack of staff time to work on such projects. Training about digitization and online platforms was the next most common choice, followed closely by a cataloging (metadata) consultant who could help with describing materials, and a team that could come to your site to scan materials. Most Effective Types of Assistance Funding staff time for digitization 39 Cataloging consultant 18 Team to do scanning on-site 16 Access to scanning equipment 17 Training on digitization and online platforms 20 B. Metadata results Drawing on the literature reviewed above, five collaborative statewide digital projects that had broad-based participation from heritage organizations were identified. They are: Project Name Number of Contributing Metadata Schema Organizations Maine Memory Project 270 Dublin Core Making of Modern Michigan 55 Dublin Core New Jersey Digital Highway 36 METS/MODS North Carolina ECHO/Digital 143 Dublin Core Ohio Memory Online 330 Dublin Core Connecticut History Online 7 Dublin Core North Carolina1 1 These started as separate projects but merged over time. Additional research was conducted to study the approach to metadata taken by each of these projects, including examination of metadata guidelines, descriptions of metadata procedures, and interviews with project staff members. Connecticut History Online was also included in this part of the research because it is the most important collaborative digital project in Connecticut and will be the basis for heritage materials in the Connecticut Digital Archive. Four of these five projects used Dublin Core as their metadata framework, although they modified it in slightly different ways. Descriptions in the evaluation/research literature and interviews with project staff confirm that Dublin Core is seen as the “lowest common denominator” for metadata, being the simplest and most flexible for those contributing materials. Dublin Core’s accessibility is the basis for its wide use in cultural heritage repositories. Dublin Core was developed with the non-specialist searcher in mind, using commonly understood terminology and aiming to be as simple to create as possible (CDP Metadata Working Group, 2006, p. 5). The Colorado-based Collaborative Digitization Program adopted Dublin Core as the standard “to promote interoperability among cultural heritage institutions” in 2006 because of its common elements, flexibility, and applications to such institutions. Dublin Core is also used by the Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH), which is supported by the federal Institute for Museum and Library Services to create a single repository of digital collections (CDP Metadata Working Group, 2006, p. 7). Ruth Anne Jones indicated that in the Making of Modern Michigan project, it would have been very difficult to get participation from the small libraries (many with only one or two people on staff and no cataloguers) if a more complex set of metadata had been required (Jones, 2014). The flip side of Dublin Core’s accessibility is a lack of depth and specificity. Katherine Wisser, who served as metadata coordinator for the North Carolina ECHO project, prefers a more detailed standard for metadata, but found that there was no better solution than Dublin Core when seeking to serve the "variety and heterogeneity of cultural heritage organizations in the state" (Wisser, 2014). When Connecticut History Online shifted from a MARC-based system to Dublin Core, they lost some of the granularity that the first system had provided, and had to concatenate fields and controlled vocabularies. Through many discussions with the ten different people involved in cataloging from the organizations participating in the project, they arrived at adaptations of qualified Dublin Core that they felt best served their core audience: K-12 educators and the general public. This meant modifying the labels on some of the fields as well as date formats to make it more “user-friendly” for this general audience, a step that was also taken by the Maine Memory Network (Amoroso, 2014; Foulke, 2014). Several elements in Dublin Core require modification in order to function well for cultural heritage collections, and these statewide projects made their own adaptions, particularly to fields such as dates (which need to be able to include estimated dates or ranges), subjects, and publishers (which are usually not traditional publishers). The Collaborative Digitization Program added a “Date Original” and a “Date Digital” field to identify chronological information; a field called “Digitization Specifications” to provide technical metadata; and a “Contributing Institution” field to distinguish these from copyright holders and publishers (CDP Metadata Working Group, 2006). The Maine Memory Network provided separate fields for exact dates, estimated dates, and date ranges; as well as creating separate fields for subject names, dates, and locations (Maine Historical Society, 2012, pp. 50-57). Digital North Carolina changed the names of some Dublin Core fields and added several others to meet its needs as a statewide database, such as "Digital Collection," "Collection in Repository," and "Contact Information" (North Carolina Digital Heritage Center). The New Jersey Digital Highway took a different approach to metadata, using the Metadata Encoding and Transcription Schema (METS) along with the Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS), packaging together the descriptive and administrative metadata for each object. These schemas offer richer descriptive metadata than Dublin Core but also require more effort on the part of catalogers. In order to simplify the process for contributing organizations, only certain fields of descriptive and administrative metadata were required, while the others were recommended (Marker, 2006). The fact that the New Jersey Digital Highway project is centered in a university library and connected to the university’s digital repository may explain the use of this more in-depth approach to metadata. The five projects that included many different organizations also took steps to make the creation and entry of metadata as user-friendly and consistent as possible. The Making of Modern Michigan, the Maine Memory Network, the New Jersey Digital Highway, and the Ohio Memory project all used web-based templates for data entry in order to provide guidelines and examples at the point of cataloging. All these projects also provided training to contributing institutions on metadata creation as well as on scanning specifications and other issues. The Maine Memory Network focused on “quality, not quantity” of records, and worked closely with participating organizations to make sure that items were only included in the database if they included contextual information that explained why they were of historical significance (Amoroso, 2014). The North Carolina ECHO project hired a metadata coordinator to conduct workshops and offer consultation, by phone or on-site, to organizations on creating high-quality metadata. This outreach effort aimed to "provide an arsenal of knowledge and skills in consistent metadata applications to as many professionals as possible" (Wisser, 2005, p. 168). Both the Maine and the Ohio projects devoted much staff time to reviewing metadata as it was submitted in order to ensure consistency; in the Maine project, staff took on the job of assigning subject headings to each record (Amoroso, 2014; Gemmill & O’Neal, 2005, p. 178). Since Connecticut History Online involved a smaller number of organizations employing professional cataloguers, it has not taken as many of these steps to facilitate the creation of descriptive records, relying instead on intensive collaborative work among the cataloguers to arrive at a common standard (Foulke, 2014). IV. DISCUSSION A. Survey Results The results of the survey show that many of the issues identified in the literature as creating challenges for the participation of smaller heritage organizations in collaborative digital projects are relevant in Connecticut. Small organizations with limited staff are not wellpositioned to embark on digitization projects when they do not have the resources to catalog their collections and are not accustomed to using controlled vocabularies and standards in describing them. At the same time, the positive attitudes towards digitization evident in the survey provide a solid foundation on which to build. All but a few of those respondents whose organizations are not currently sharing a significant number of images online believe that it would be beneficial for them to do so. Almost all the respondents saw the potential benefit to their organizations of digitizing and sharing collections information, as a way to reach a broader audience, serve their constituents better, and help make connections with other institutions. Another important finding is that almost all the organizations surveyed are already digitizing at least some of their collections items for certain purposes, so it may not be a big step to move towards a more systematic approach. The survey also identified specific steps that could be taken to assist smaller heritage organizations in participating in digitization projects. Specifically, there is a strong demand for funding that would enable organizations to devote additional staff time to digitization. There is also strong interest in further training on digitization and sharing of collections information. Such training should address issues of copyright and permissions (identified as a concern by a number of respondents), as well as guidance in selecting which material from a collection to digitize. Finally, there is interest in getting help with metadata creation for digitized materials, and some organizations are interested in a mobile scanning team that could come to their site and scan materials. Most organizations seem less concerned with access to scanning equipment than with other barriers. All of these steps have been taken by various digitization projects in other states and could be developed based on those examples. B. Metadata practices The survey of metadata approaches in different statewide collaboration digitization projects indicates that Dublin Core is the framework of choice for projects that want to be as inclusive as possible of many different heritage organizations, especially smaller organizations that do not have professional cataloguers on staff. Despite the historically-rooted differences in cataloging practices between libraries, archives, and museums, Dublin Core is flexible enough to effectively describe - at least on a basic level - the different kinds of materials that heritage organizations in Connecticut hold in their collections, from archival material to three-dimensional objects. With minor modification, the labelling of Dublin Core fields makes sense to the general audience that is the core user base for heritage organizations in Connecticut. Furthermore, using Dublin Core is a good choice from the perspective of interoperability, as it is compatible with the system used by the Digital Public Library of America, as well as the OAI-PMH. In order to make the process of metadata creation as easy and consistent as possible, projects in other states have provided detailed guidelines for each of the Dublin Core fields, with examples, often through an online template for entry of records. Because the Dublin Core standard is quite flexible, it is important for a statewide project to spell out how each field should be used in order to maintain consistency, and to provide some staff oversight over records as they are uploaded into the system. V. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS It is clear from looking at digitization projects in other states that have succeeded in including many different heritage organizations that this took dedicated resources and a conscious effort to include and empower smaller organizations. Outreach and training for heritage organizations - about the selection of items to be entered into the project, scanning requirements, and the creation of metadata - are important elements of creating a broad-based collaborative digital collection. Projects developed so far in Connecticut - notably Connecticut History Online and Connecticut Archives Online - have relied on the skills of professional curators and cataloguers, working with established standards, to ensure quality and consistency. In order to expand such projects to incorporate the wealth of material from smaller heritage organizations, a different approach is necessary. The benefits of making a concerted effort to include many different organizations include creating a richer and more representative collection of the state's cultural heritage, by drawing on a wider variety of collections; and assisting smaller organizations to serve broader audiences and make connections across institutions by including their materials. Recommendations: - Provide small grants to organizations to support staff time on selection, digitization, and description of materials. - Create a staff position to coordinate content related to Connecticut history and heritage as the Connecticut Digital Archive takes in material from different organizations in the state. This person would be the primary point of contact between heritage organizations throughout the state and be responsible for outreach, training, and monitoring of submitted material. - Develop detailed guidelines for entering metadata (using Dublin Core fields adapted to the needs of the Connecticut Digital Archive), with examples. Specify which fields are mandatory and which are recommended. A web-based template for entering this data would be preferable. - Offer training through workshops on selection, digitization and metadata best practices, and platforms for sharing materials several times a year in different parts of the state, as well as onsite consultations and telephone support. Workshops and presentations can be coordinated by the Connecticut League of History Organizations, building on the "Digitization 101" workshop offered in 2013. REFERENCES About Connecticut History Online. (2012). Connecticut History Online. Retrieved July 22, 2013, from http://www.cthistoryonline.org/cho/project/index.htm Amoroso, K. (2014, March 24). Telephone interivew. Bernier, M., Costa, K., Ecenarro, T., & Keagle, M. (2013). Newport Cultural Consortium: Creating a Regional Online Catalog. Presented at the New England Archivists conference, College of the Holy Cross. Bishoff, L. (2004). The Collaboration Imperative: Library Journal, 129(1), 34–35. CDP Metadata Working Group. (2006). Dublin Core Best Practices, Version 2.1.1. Retrieved June 2, 2013, from www.mndigital.org/digitizing/standards/metadata.pdf Connecticut Digital Archive Launches Softly. (2013, January 11). Connecticut Digital Archive. Retrieved from http://blog.ctdigitalarchive.org/2013/01/11/connecticut-digital-archivesoft-launched/ Connecticut History Online. (2012). Connecticut History Online. Retrieved July 24, 2013, from http://www.cthistoryonline.org/cdm/search/collection/cho/searchterm/hungarian/order/no sort Digital Collections 101: An Introductory Workshop. (2013). Conservation ConneCTion. Retrieved June 18, 2013, from http://www.conservationct.org/content/digital-collections101-introductory-workshop-may-6-2013 Downer, S., Medina, S., Nicol, B., & Trehub, A. (2005). Alabama Mosaic: sharing Alabama history online. Library Hi Tech, 23(2), 233–251. doi:10.1108/07378830510605188 Dublin Core Metadata Element Set, Version 1.1. (2013). Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. Retrieved June 13, 2013, from http://dublincore.org/documents/dces/ Foulke, K. (2014, March 10). Telephone interview. Gemmill, L., & O’Neal, A. (2005). Ohio Memory Online Scrapbook: creating a statewide digital library. Library Hi Tech, 23(2), 172–186. doi:10.1108/07378830510605142 Hubs. (2013). Digital Public Library of America. Retrieved June 2, 2013, from http://dp.la/info/about/who/partners/hubs/ Jeng, J. (2008). Evaluation of the New Jersey Digital Highway. Information Technology and Libraries, 27(4), 17–24. Jones, R. A. (2005). Empowerment for Digitization: Lessons learned from The Making of Modern Michigan. Library Hi Tech, 23(2), 205–219. doi:10.1108/07378830510605160 Jones, R. A. (2014, March 13). Telephone interview. Maine Historical Society. (2012). Contributing Partners’ Manual: Your Guide to Digitizing and Cataloging Historical Items for Maine Memory Network. Maine Historical Society. Retrieved from http://www.mainememory.net/share_history/share_resources.shtml Marker, R. (2006). Repository Metadata Guidelines. Rutgers University Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.njdigitalhighway.org/documents/metadata-guidelines.pdf Mt. Auburn Associates, Inc. (2003). Evaluation of the Maine Memory Network. Retrieved from http://ntiaotiant2.ntia.doc.gov/top/docs/eval/pdf/236001006e.pdf Nodler, H., & Botticelli, P. (2009). Case Example: Museum Data Exchange Good Things Come to Those Who Share. Retrieved from http://www.u.arizona.edu/~hnodler/portfolio/digin671MDEcase_final.pdf NovaMuse: About. (2013). NovaMuse. Retrieved June 13, 2013, from http://www.novamuse.ca/index.php/About/Index Past Perfect Client List. (2013). Past Perfect Museum Software. Retrieved from http://www.museumsoftware.com/clientlist.html Roel, E. (2013). The MOSC Project: Using the OAI-PMH to bridge metadata cultural differences across museums, archives, and libraries. Information Technology and Libraries, 24(1), 22–24. The Lexicon. (n.d.). In Past Perfect Museum Software User’s Guide. Retrieved from http://www.museumsoftware.com/v5ug/pdf/PP5-10lex3.pdf Waibel, G. (2010). Museum Data Exchange: Learning How to Share. D-Lib Magazine, 16(3/4). Retrieved from http://www.dlib.org/dlib/march10/waibel/03waibel.html What is CAO. (n.d.). Connecticut Archives Online. Retrieved July 22, 2013, from http://library.wcsu.edu/cao/about Wisser, K. (2005). Meeting Metadata Challenges in the Consortial Environment: Metadata coordination for North Carolina Exploring Cultural Heritage Online. Library Hi Tech, 23(2), 164–171. doi:10.1108/07378830510605133 Wisser, K. (2014, March 26). Telephone interview. Wykoff, L., Mercier, L., Bond, T., & Cornish, A. (2005). Columbia River Basin Ethnic History Archive: A tri-state online history database and learning center. Library Hi Tech, 23(2), 252–264. doi:10.1108/07378830510605197 Wythe, D. (2006). Review of: Collaborative access to virtual museum collection information seeing through the walls, by Bernadette Callery. American Archivist, 69(2), 543–546. Appendix 1: Invitations to participate A. Email sent to participants in “Digitization 101” workshops held in May and June, 2013 Dear fellow Digitization 101 participants, I’m writing to ask you to complete a survey I am doing as part of my research toward my Library Science degree at Southern Connecticut State University. I am conducting a research study to identify barriers to museum and historical societies’ participation in statewide digital projects. I would greatly appreciate your help in filling out the survey, which you can access online at http://…………….. No personal information will be collected and your organization will not be identified, but the results of the survey will help guide efforts to encourage the participation of history organizations in digital projects in the state. Sincerely, Elizabeth Rose, Fairfield Museum & History Center Please feel free to contact me with any questions: elizabethruthrose@gmail.com B. Email sent to institutions listed as using Past Perfect museum software To the curator, collections manager, or librarian: As part of my work toward the Master’s in Library Science degree at Southern Connecticut State University, I am conducting a research study to identify barriers to museum and historical societies’ participation in statewide digital projects, like Connecticut History Online. I would greatly appreciate your help in filling out the survey, which you can access online at http://…………….. The survey consists of 14 multiple-choice questions and should take no more than 10 minutes to complete. No personal information will be collected and your organization will not be identified, but the results of the survey will help guide efforts to encourage the participation of history organizations in digital projects in Connecticut. Sincerely, Elizabeth Rose, Fairfield Museum & History Center Please feel free to contact me with any questions: elizabethruthrose@gmail.com C. Email sent by Connecticut League of History Organizations Connecticut League of History Organizations March 27, 2014 Take our survey and help advance the heritage community's knowledge about directions in digitization A Special Request from A Colleague I am writing to ask you to complete a survey I am doing as part of coursework for a Library Science degree at Southern Connecticut State University. I am conducting a research study to identify barriers to museum and historical societies' participation in statewide digital projects, and I would like to include your organization. I would greatly appreciate your help in filling out the survey, which you can access online at http://goo.gl/6w4Tgv No personal information will be collected and your organization will not be identified, but the results of the survey will help guide efforts to encourage the participation of heritage organizations in digital projects in the state. Please feel free to share the survey with co-workers and colleagues. Sincerely, Elizabeth Rose, Fairfield Museum & History Center Please feel free to contact me with any questions:elizabethruthrose@gmail.com Connecticut League of History Organizations 37 Broad Street Middletown, CT 06457 liz@clho.org 860-685-7595 End your promotion with a kick - consider a postscript to reinforce oecticut League of History Organizations Appendix 2: Survey instrument Thank you for participating in this survey about collaborative digital projects in Connecticut, which is part of a research study undertaken by Elizabeth Rose, a graduate student in Library Science at Southern Connecticut State University. The survey consists of 14 questions and should not take more than 15 minutes to complete. Of course, your participation is voluntary and you may stop taking the survey at any time. All data about your organization and role will be kept anonymous. Completion of this survey indicates your consent to having responses used in this research. For questions about the research project, please contact Elizabeth Rose at elizabethruthrose@gmail.com or Southern Connecticut State University’s Human Research Protection Program at (203) 392-5243. 1. Which of the following best describes your organization? a. b. c. d. e. local historical society museum library that includes historical collections special collections/archive at a college or university other 2. Which of the following best describes how your organization manages its collection? a. b. c. d. Part-time volunteers Part-time curator or archivist Full-time curator or archivist Two or more full-time staff members responsible for collection 3. Which of the following best describes your role in the organization? a. b. c. d. e. board member or other volunteer director of organization curator archivist librarian 4. How would you describe the items in your collection? a. Primarily archival materials such as family papers, organizational records, and photographs b. Primarily historical objects such as furniture, clothing, tools, and/or household items c. Primarily paintings and other works of art d. A combination of all of the above 5. Which of these statements about your collection is most accurate? a. The collection is fully catalogued (i.e., staff can find basic information for each item) b. The collection is mostly catalogued c. About half of the collection is catalogued d. Less than half of the collection is catalogued 6. Which of these methods do you use to keep track of your collection? a. b. c. d. e. f. Paper files or log book Excel spreadsheet Database program (FileMaker, Access) Past Perfect software The Museum System (TMS) software Other [write in] 7. When you are cataloging materials from your collection, do you use any of these standards? a. b. c. d. e. Library of Congress subject headings Describing Archival Collections (DACS) Art and Architecture Thesaurus other [write in] No, we use terms that our organization has decided on 8. Does your organization currently scan or digitally photograph collections items for purposes such as research requests, reproduction in publications, or use in exhibitions? a. yes b. no 9. How familiar are you with the following digital projects in Connecticut? (circle one response for each project) Connecticut History Online Connecticut Archives Online Connecticut Digital Archive I have not heard of it Treasures of Connecticut Libraries I have not heard of it I have not heard of it I’ve heard of it or have used it I’ve heard of it or have used it I’ve heard of it or have used it I’ve heard of it or have used it My organization has contributed content to it My organization has contributed content to it My organization has contributed content to it My organization has contributed content to it My organization would like to contribute content to it My organization would like to contribute content to it My organization would like to contribute content to it My organization would like to contribute content to it I have not heard of it 10. Which of these statements is most accurate? a. My organization currently shares a significant number of images from our collection online (on our website, Facebook page, or other site) b. I think it would be beneficial for our organization to share images from our collection online, but we have not done it very much so far c. I do not think it would be beneficial for our organization to share images from our collection online 11. Which of these statements is most accurate? a. I have a good idea of which items in our collection are most worth digitizing, because of their unique historical value and interest to the public. b. I could use guidance in choosing which items in our collection are most worth digitizing. 12. What would be the most important benefits to your organization of sharing information about its collections? a. reaching a broader audience b. making material available to teachers and students c. making material available beyond our limited library hours d. connecting with other institutions with shared collection themes e. other [write in] 13. What are the main barriers to sharing more of your collection online? a. We don’t know the best way to share images online b. We don’t have staff time to select and digitize material c. We don’t have equipment to digitize material d. We don’t have time to describe material that’s put online e. We are concerned about people using images from our collection without permission 14. What kind of help would be most likely spur your organization to do more with digitizing and sharing collections online? a. training/information sessions about digitization and online sharing b. access to equipment for scanning c. a team that could come to your site and scan materials d. a cataloging consultant who could help with describing materials e. funding for additional staff time