- e-Lis

advertisement

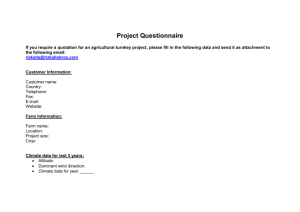

Assessment of farmer’s perception on soil quality deteriorating and crop yield reduction in Sudan Savannah of Sub-Saharan Africa by 2020 *S. Usman1, S. S. Noma2, A. Makai3 and A. Aminu4 1 Natural Resources Institute, Agriculture, Health and Environment Department, University of Greenwich at Medway, UK ME4 4TB us06@gre.ac.uk 2 Department of Soil Science, Faculty of Agriculture Usuman Danfodiyo University Sokoto Nigeria 3 Sustainable Agriculture, College of Agriculture Zuru, Kebbi State Nigeria 4 Department of GS Kebbi State University of Science and Technology Aleru, Kebbi State Nigeria ABSTRACT Assessment of farmer’s perception on soil quality deteriorating and crop yield reduction has been carried out in the Sudan Savannah (SS) of Kebbi State Nigeria with specific objective to provide report a report on soil quality deterioration and crop yield reduction using IPCC climate change impact report on Africa by 2020. The assessment was made using face-toface-verbal-interview. The interview was divided into four rounds according to four questions. Absolutely, it is reported that some farmers have considered climate change impact as one of the major agricultural problems that will take part in deteriorating soil quality and yield reduction by 30%, and some by 50%, while few of these farmers have the opinion of 70% by 2020. Generally, the fact that the climate change impact will cause yield reduction for up to 50% in Africa by 2020 remained an open debate issue for most farmers in the SS. INTRODUCTION It is well known that farmers are expert because of the daily experiences, which they have been acquiring year after year during their farming activities. Their experiences are important for future agricultural management; because farmers particularly in Africa were reported to have developed intricate systems of gathering, predicting, and interpreting agricultural related problems for future management (IPCC, 2001; IPCC, 2007). In the Sudan Savannah (SS) of Kebbi State Nigeria, farmers are much more concern about the soil and crop yield performances. They are very worried on low fertility level and poor soil quality, primarily because of low annual crop yield. Therefore, they are in position to contribute reasonably with their experiences in the identification of soil-crop related problems such as soil quality deteriorating and low annual crop yield for future agricultural management. Studies in Nigeria (Raji et al., 2000) and Kenya (Defoer et al., 2000) reported that farmers are able to use their experiences on weather condition such as high number of rainfall per year, hottest season in a year, nature of wind in dry season as well as physical soil condition and crop yield performances to judge for present and future agricultural soil and crop problems. Their experiences were considered as the basis for local-level decision-making in many rural communities; because of its value not only for the culture in which it evolves, but also for scientists who are working to improve awareness in rural localities (IPCC, 2007). In the present study, the farmers based knowledge in agriculture was used to know the level of soil quality deterioration, crop yield reduction and the certainty of the predicted IPCC report on Africa based on climate change in relation to soil and crop production in the SS. Therefore, the general objective of this study was to provide a report on soil quality deterioration and crop yield reduction based on farmer’s perception of climate change impacts using IPCC climate change impact report on Africa by 2020. 1 MATERIAL AND METHOD Study area The SS of Kebbi State Nigeria is one of the most agriculturally viable environments in northern States of Nigeria. The total landmass of northern Nigeria including the SS is 75.9% of the country (Clara et al., 2003). The region lies between latitude 11o and 13oN and longitudes 4o and 15oE, bordering the Nigerian States of Sokoto to the north, Zamfara to the east and Niger to the south (Figure 1). In sub-Saharan Africa, the SS borders the nations of Niger republic to the west and Benin republic to the southwest. The total land area of Kebbi State including the SS is 36,229 km2 of which 12,600 km2 is under agriculture (KARDA, 1997). 11o N 15o N Sub-Saharan Africa Niger Republic Benin Kebbi State Nigeria 4o E Zamfara State Niger State 15oE North-West Nigeria West Africa 1:7 100 000 Nigeria on same scale as general map Figure 1: Map of Kebbi State located in Nigeria from sub-Saharan African The SS of Kebbi State has five Local Government areas: Arewa, Argungu, Augie, BirninKebbi and Dandi. These areas have been dominated by the tribes of Hausa and nomadic Fulani ethnic groups, whose sources of income depend greatly on farming systems. There are also other ethnics groups: Zabarmawa and migrants of Yoruba and Ibo tribes. These tribes are considered as the minority groups in the zone (Gordon, 2005). However, with the exception of Zabarmawa, all the Yoruba and Ibo tribes in the zone were migrants from the south-west and south-east zones of Nigeria, respectively. Weather and climate condition The SS lies at the extremely climate condition of sub-Saharan Africa known as Sahel region. The region has a tropical weather conditions with three seasons: rainy, dry and hot. Rainy (wet) season starts normally from May/June to September/October. Dry season starts from December to early April. And hot season begins in April through May. The annual rainfall in the SS is variable and declining, being 600 mm to 875 mm and on average 650 mm during the period 1995-2010, against 815 mm over 1962-71; and was only 509 mm in 1993 as reported by Oluwasemire (2004). The annual monthly temperatures are between 25oC-45oC. Surface landform type and land use activities The type of surface landform in the SS is divided into two important agricultural lands: the fadama commonly found within Argungu, Augie, Birnin Kebbi, and dryland partly found all over the region but is more occupied within Arewa and Dandi areas. The name dryland was 2 derived from the word arid which implies prolonged dryness, used only with respect of climate itself (Squires and Tow, 1991; Creswell and Martin, 1998). In contrast, the name fadama is a local name given to seasonally flooded areas by Hausa tribes in northern Nigeria. Fadama is an agricultural land which is seasonally flooded during the period of rains: these recede during the dry season leaving a coating of alluvial clay soil. However, the fadama agricultural lands in the SS lies within latitude 12o37’26.64”N and longitude 4o23’15.69”E, whereas the dryland lies within the latitude 12o46’35.46”N and longitude 4o7’55.23”E. Farming systems in these areas are called ‘dryland farming’, and was defined by Farage et al. (2007) as an agricultural technique for cultivating land which received little rainfall. The major agricultural activities in the dryland areas of the SS include crop production system and pastoralist nomadic system. Physically, the dryland farming in the SS may be classify into mono-cropping where only millet is grown; intercropping where millet, sorghum and cowpea are grown; and crop rotation where millet-sorghum-cowpea are grown yearly. Economically, the fadama lands in the SS support and host high value of cereals (mainly rice (major), wheat and maize) and horticultural crops in raining and dry seasons through flood recession and irrigation system. They also constituted the main source of fodder and the grazing for livestock under transhumant and pastoralists farming systems. IPCC (2007) report on climate change impact in Africa The Third Assessment Report of the IPCC working groups on climate change impact in Africa have identified and highlighted a range of impacts and problems associated with climate change and its variability in African continent (IPCC, 2007). These range of climate change impacts as identified by the working group include decreases in grain yields, changes in runoff, increased droughts and floods, as well as significant plant and animal species extinctions and associated human livelihood impacts. However, in line with these climate change impacts, the present study has focussed on two important factors that are physically and socially daily news among the farmers in the SS namely: soil quality deterioration and annual crop yield reduction. Therefore, the third assessment report was used as complete materials to develop and formed the questions, which have been used to collect the necessary information from farmers on climate change impact as related to soil and crop in the SS. The questions are grouped into four. First, ‘Have you notice climate change in your locality?’ Second, ‘Is climate change affecting your agricultural farms? Third, ‘What major agricultural problem has climate change caused so far?’ and Fourth, ‘What do you believe would happen to your farms by 2020 in term of soil-yield quality?’ (Refer to Appendix 1 for questions: translated to English from Hausa language). These four questions were developed based on assumption that farmers in the SS are very aware with the climate change and its impact but not knowing that the local name they have been using (i.e. “chanjin yanayi or damana”) to describe or define the context is the same as ‘climate change’ as strictly understood by global environmental scientists. Interview format Face-to-Face-Verbal-Interview was carried out in rural areas of Argungu, Bagaye, Birnin Kebbi, Bui, Fakon-Sarki, Kangiwa and Tungar-Dangwari villages. Farmers were selected randomly. The respondents are all males. The total size of the participants in each village is one hundred (i.e. 100 x 7 = 700 individual farmers). The interview was divided into four rounds according to the first, second, third and fourth questions, consecutively. In the first round, one hundred participants in each village were given chance to answer the first question. In the second round, the numbers of positive respond in the first question were only considered for the second round. In the third and fourth rounds, the number of individuals 3 positively responded to question been asked in the second round were considered for third and fourth questions. Each interview was recorded using pen and exercise book, lasted between 55 and 95 minutes for a period of 1 day in each village (Saturday and Sunday). However, at the end of each interview, the recorded information was then reorganised in another new exercise book and finally saved into the laptop computer. Finally, the recorded data was analysed, mathematically (refer to Appendix 2). RESULTS The results of the present study are presented in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4. The total numbers of farmers who respond positively and negatively as well as those who have not respond at all, were presented in Table 1. The percentage analyses of the overall results are given in Tables 2, 3 and 4. Table 1: Responses of farmer’s perceptions on soil erosion impact in Kebbi State. Questions are based on IPCC climate change projections of yield reduction by 50% in 2020 in Africa 1st Round (%) Positive respond Negative respond No respond 2nd Round (%) Positive respond Negative respond No respond 3rd Round (%) Erosion Yield reduction No respond 4th Round (%) SQD+YR by 70% SQD+YR by 50% SQD+YR by 30% @ Q1. Have you notice climate change in your locality Bagaye Birnin Bui Fakon- Kangiwa TungarKebbi Sarki Dangwari 53 59 62 68 38 70 76 21 26 18 9 33 3 24 26 15 20 23 29 27 0 Q2. Is climate change affecting your agricultural farms? Argungu Bagaye Birnin Bui Fakon Kangiwa TungarKebbi -Sarki Dangwari 43 46 55 68 35 59 50 6 8 6 0 3 8 23 4 5 1 0 0 3 3 Q3. What major agricultural problem has climate change caused so far? Argungu Bagaye Birnin Bui Fakon Kangiwa TungarKebbi -Sarki Dangwari 19 16 26 33 12 36 19 13 27 21 25 17 23 18 11 3 8 10 6 0 13 Q4. What do you believe would happen to your farms by 2020 in term of soil-yield quality? Argungu Bagaye Birnin Bui Fakon Kangiwa TungarKebbi -Sarki Dangwari 3 0 7 2 6 11 1 14 19 23 21 19 33 27 26 27 25 45 10 15 22 Argungu SQD+YR = SQD means Soil Quality Deteriorating and YR means Yield Reduction According to Table 1, in the first round of the interview there were significant respond to question been asked. At Argungu, Bagaye, Birnin Kebbi, Bui, Kangiwa and TungarDangwari more than 50% of the farmers have responded positively but varied in numbers of negative respond and numbers of no respond, accordingly. By rank, in the first round the highest positive respond was recorded in Tungar-Dangwari (76%), Kangiwa (70%), Bui (68%), Birnin Kebbi (62%), Bagaye (59%), and Argungu (53%). Considerably, 21%, 26%, 18%, 9%, 33%, 3%, and 24% are percentage numbers of farmers who have responded negatively in the respective villages. 4 In the second round where the percentage numbers of positive respond from the first round were considered, there were considerable variations in terms of positive and negative responses to question been asked. On positive respond, 43, 46, 55, 68, 35, 59 and 50 are numbers of individual farmers agreed that climate change is one of the major factors affecting surface agricultural soils in Argungu, Bagaye, Birnin Kebbi, Bui, Fakon-Sarki, Kangiwa and Tungar-Dangwari, respectively. By percentage analysis (Appendix 2), these numbers of individual farmers correspond to 81%, 78%, 88%, 100%, 92%, 84% and 66% equivalently. These means, the remaining extra 11% and 8%, 14% and 8%, 10% and 2%, 0% and 0%, 8% and 0%, 12% and 4%, and 30% and 4% goes to negative and no-respond as presented in Table 2. According to this Table 2, the highest percentage positive respond is 100% recorded at Bui and the lowest is 66% recorded at Tungar-Dangwari. 30% and 0% are the highest and lowest percentages negative respond recorded at Tungar-Dangwari and Bui respectively. The percentage numbers of no-respond also vary, been high (8%) at Argungu and Bagaye and low (0%) at Bui and Fakon-Sarki sites. Table 2: Analytical data on percentages respond of farmers on question 2 in 2nd round % Positive Negative No-respond Argungu (%) 81 11 8 Bagaye (%) 78 14 8 Birnin Kebbi (%) 88 10 2 Bui (%) 100 0 0 FakonSarki (%) 92 8 0 Kangiwa (%) 84 12 4 TungarDang. (%) 66 30 4 In the 3rd round of the assessment, the data analysed (Table 3), shows that there were significant farmer’s respond with regard to erosion and yield reductions as two of the major agricultural problems in the State. As presented in Table 3 blow, the farmer’s opinion between these two agricultural problems varies. By comparisons, the percentages farmer’s respond to erosion as contrary to yield reduction are high in Argungu (40% against 30%), Birnin-Kebbi (47% against 38%), Bui (48% against 37%), Kangiwa (61% against 39%) and Tungar-Dangwari (38% against 36%). Reasonably (Table, 3), there were only high percentages (49% and 58%) of farmer’s respond to yield reduction against soil erosion (34% and 35%) in Fakon-Sarki and Bagaye accordingly. The percentages number of no-respond are 26%, 7%, 15%, 15%, 17%, 0%, and 26%. These numbers are recorded at Argungu, Bagaye, Birnin-Kebbi, Bui, Fakon-Srki, Kangiwa and Tungar-Dangwari, respectively. Considerably, all the farmers in Kangiwa responded significantly to both erosion (61%) and yield reduction (39%), but for the others villages some few numbers of farmers have not respond at all (refer to Table 1: 3rd Round). By observation, high percentage numbers of no-respond are 26% each from Argungu and Tungar-Dangwari villages. Table 3: Analytical data on percentages respond of farmers on question 3 in 3rd round (%) Erosion Yield reduction No respond Argungu (%) 44 30 26 Bagaye (%) 35 58 7 Birnin Kebbi (%) 47 38 15 Bui (%) 48 37 15 FakonSarki (%) 34 49 17 Kangiwa (%) 61 39 0 TungarDang. (%) 38 36 26 Finally, Table 4 shows the opinions of farmers with regard to soil quality deteriorating and yield reduction by 2020 in the SS. According to Table 4, majorities of farmers in Argungu (66%), Bagaye (59%), Birnin Kebbi (45%), and Bui (66%) agreed that by 2020 the 5 agricultural production would only be affected by 30% due to soil quality deteriorating and yield reduction. However, this is not the opinions of most of the farmers in Fakon-Sarki, Kangiwa and Tungar-Dangwari. In these 3 villages, 54%, 56% and 54% of the farmers respectively agreed that by 2020, the total agricultural yield production will go down by 50%. Generally, only few of these farmers agreed that the agricultural production will drastically reduced to 70% by 2020. The percentage numbers of these farmers in Argungu, Bagaye, Birnin Kebbi, Bui, Fakon-Sarki, Kangiwa and Tungar-Dangwari are 7%, 0%, 13%, 3%, 17%, 19% and 2%, respectively. Table 4: Analytical data on percentages respond of farmers on question 4 in 4th round (%) SQD+YR by 80% SQD+YR by 50% SQD+YR by 30% Argungu (%) 7 33 66 Bagay e (%) 0 41 59 Birnin Kebbi (%) 13 42 45 Bui (%) 3 31 66 FakonSarki (%) 17 54 29 Kangiwa (%) 19 56 29 TungarDang. (%) 2 54 44 DISCUSSION Base on the facts that have been observed as perceived by majority of farmers in the SS, there are some evidences of soil quality deteriorating and yield reduction (Table 1). Also, there would be expectations of yield reduction between 30%, 50% and 70% by the year 2020 (Table 4). These two areas of observations are worthy of consideration with regard to results presented. By percentages (Tables 2, 3), the baseline data on farmer’s perception indicates important responses to questions been asked throughout the interview. More importantly, in the third and fourth rounds it is clear that the problems of soil erosion and yield reduction are in mine of most farmers. Farmers are aware of these problems and have understood their future consequences. Mathematically, majority of the respondents (Table 2) in all the villages agreed that climate change affects their agricultural lands. Farmers in these villages are very aware of climate change because of the seasonal variations in annual rainfall, monthly temperature and wind. Since, farmers in the SS have known climate change in their native language as “chanjin yanayi”, and indeed, they are very aware of the problems associated with agricultural, soil and environmental conditions; because traditionally, they used common and well-known term in their native language: ‘damana tayi kyau’ or ‘damana batayi kyau ba’ – simply referring to good season or bad season. One of the potential traditional measures in respect to farmer’s indigenous knowledge on climate change in the SS, is available annual data record base on numbers of monthly rainy. Another potential traditional measure might be related to decrease in annual yield reduction because most of the farmers have complained much about drought and flooding due to shortage of rainfall in the first three to four months of the rainy season, but more rainfall than normal in the last two months of the rainy season. It is well known that rainfall is highly needed during the first few months of plant growth and has less important in the last 1 month, because at this time the farm produces is well matured ready to be harvested. Looking at the numbers of farmer’s responses (Table 1) on what major agricultural problems has climate change caused in the SS, it become clear that erosion and yield reduction are real in most of the affected areas as similarly noted by Usman (2007). Thus, the ultimate effect on agricultural production and low yield in the SS, relates to the decreased in soil and land quality. For this, with farmer’s perception of erosion as one of the major agricultural problems caused by climate change, it is true that the soil erosion impact on land and people 6 observed by previous report (KARDA, 1997) are in many ways connected with issues of climate change. At the same time, soil erosion might be also consider as one of the environmental problem that would possibly cause 50% yield reduction by year 2020 as predicted by IPCC (2007) for most African regions. It is for this reason that the final question was set up to clarify whether if the yield reduction in the SS will go down by 50% by 2020 or less or even more than 50%. By percentages (Table 4) majority of farmers have the opinion that the yield will reduce by 30% to 50% in 2020. In total, the largest percentage number of respond (338%) comes from individual farmers who believe that the soil quality and yield production will only reduce by 30% due to present climate change crises. About 311% total percentages individual farmers in all the villages also agreed that by year 2020, the total crop yield and quality of soil function would go down for up to 50%. Reasonably, 61% total percentage individual farmers in all the villages have the opinion that the soil quality and yield production would drastically decrease to 70%. The reasons underlying the farmer’s different opinions with regard to this problem cannot be readily advanced, but they could be related to different experiences they have on their daily farming activities, historically. Also, it is necessary to understand that the farmers perceived the stated problems because they are very aware that physically the surface soils have deteriorated and the annual crop yields have also reduced than normal. Farmers consider climate change as one of the several factors increasing soil erosion, poor soil quality and low annual crop yields in their respective areas. Other important factors considerably related to these problems in the study areas as elsewhere similar sub-Saharan African regions, are social, economic, population crises and poverty (Eswaren et al., 2001). These factors are seemed to have integrated with climate change and caused soil deterioration and yield reduction in most of the affected areas of the SS. If this is the case, then the environmental soil changes will continue to occur because of decrease plant canopy, vegetation cover, biomass disappearances, and very poor soil textural quality. Thus, in this circumstance the likelihood that the farmer’s perception of climate change impact on deteriorating soil quality and reducing annual crop yields by 30% or 50% or 70% in 2020 will be reasonably possible. By consideration, increase in future soil lost due to soil erosion in the major affected areas, has significant relations with farmer’s perception on soil quality deteriorating and yield reduction by 2020. Therefore, the ultimate future reduction in crop yield and soil quality deteriorating of agricultural soils by 2020 in SS, relates to the decreased in soil productivity and quality. This may subsequently lead to decrease in overall agricultural outputs and increase in poverty and hunger as well as reduce in government revenue, total national food security and availability of raw agricultural materials for industries as similarly reported by IFPRI (2009) for most of the sub-Saharan African regions. The underlying assumption here is that the farmers have only used the daily experiences of their farming process and history of annual yield reduction to answer the questions been asked; while many of the future projected data in relation to soil quality deteriorating (e.g. Put et al., 2004; Bai and Dent, 2008) and yield reductions (e.g. Schmidhuber and Tubiello 2007; IPCC, 2007) were based on scientific models and facts. Yet, it is important to note that the results of this assessment was based on the fact that the SS has been part of Africa and is absolutely part of IPCC (2007) report on climate change impact. Therefore, the farmer’s perception of soil quality deteriorating and yield reduction by 2020 in the SS should be given 7 special consideration for future management decision making as similar did in Zimbabwe (Murwira et al., 2001). On the other hand, the farmer’s perception of climate change is only a yield oriented but not quantitative scientific field data. There is no misleading point in this statement because yield decline predicted by farmers by 2020 in Kebbi State, although in line with IPCC report on Africa; however, this could be caused by a variety of factors including poor surface soil condition, low nutrient content within the plant root depth, poor soil textural quality as well as adverse weather conditions, invasion of weeds, and soil physical deterioration (Hartemink, 2006). CONCLUSION The farmer’s perception on soil deteriorating and yield reduction projected by IPCC on Africa by 50% in 2020 was assessed in the SS. The assessment was made using face-to-faceverbal-interview. The interview was divided into four rounds according to four questions. In the first round, more than 50% of the farmers in Argungu, Bagaye, Birnin Kebbi, Bui, Kangiwa and Tungar-Dangwari responded positively to the question been asked. In the second round, 60% to 100% responded positively in all the villages; and in the third round, erosion and yield reduction were considered as the two major agricultural problems in all the villages. In fourth round, majority of farmers in Argungu, Bagaye, Birnin Kebbi, and Bui agreed that by 2020 the agricultural production in Kebbi State would be affected by 30% yield reduction, while in Fakon-Sarki, Kangiwa and Tungar-Dangwari 54%, 56% and 54% of the farmers respectively agreed that by 2020, the total agricultural yield production will go down by 50%. Overall, it can be conclude that the climate change impact is real and that the farmers in the SS are very aware of this impact, however, the fact that the climate change impact will be up to 50% in Africa by 2020 remained an open debate issue for most farmers in the SS. Absolutely, it is believe that some farmers have considered climate change impact as one of the major agricultural problems that will take part in deteriorating soil quality and yield reduction by 30%, and some by 50%, while few of these farmers have the opinion of 70% by 2020. Therefore, a similar research investigation in the same region will show further certainty or uncertainty of this result in future. Thus, effort should be make in trying to verify the quality of the present study for best climate change adaptation programme in Africa. Acknowledgement I thank the rural farmers of the SS who have participated and contributed toward the success of this study. As this work is part of Kebbi State Government effort to improves academic and research development in the State, special thanks goes to the State Government under the administration of Alhaji Sa’idu Usuman Nasamu Dakin-gari. REFERENCES Bai, Z. G and Dent, D. L. (2008). Land Degradation and Improvement in Tunisia 1. Identification by remote sensing: GLADA Report 1f, 1e Version August 2008. World Soil Formation: ISRIC and FAO. Clara, E., Suleiman, M., Mairo, M., Ann, W. J., Bilkisu, Y. H. and Saharadeen, Y. (2003). Strategic Assessment of Social Sector Actions in northern Nigeria: Draft Report. Assessment team lead by Clara and colleagues. Northern Assessment, Abuja, Nigeria. Pp 2-5. 8 Creswell, R. and Martin, F. W. (1998). Dryland farming: Crops and techniques for regions. ECHO, USA. p 1. Defoer, T., Budelman, A., Toulmin, C. and Carter, S. E. (Eds.) (2000). Building common knowledge: participatory learning and action research: Managing Soil Fertility in the Tropics. Series No.1. KTT Publication. IIED, FAO, CTA and KIER. Royal Intitute, Amsterdam, Netherlands, pp165-166. Eswaran, H., Lal R. and Reich, P. F. (2001). An overview: “Land degradation” International Conference on Land Degradation and Desertification, Khon Kaen, Thailand. Oxford Press, New Delhi, India. Farage, P. K., Ardö, J., Olsson, A., Rienzi, E. A., Ball, A. S. and Pretty, J. N. (2007). The potential for soil carbon sequestration in three tropical dryland farming systems of Africa and Latin America: A modelling approach. Soil and Tillage Research, vol.94, Issue 2, June 2007:457-472. Gordon, R. G. Jr. (2005). (ed) Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. 1272 pp. Hartemink, A. E. (2006). Assessing soil fertility decline in the tropics using soil chemical data. Advances in Agronomy, Volume 89. Elsevier Inc. IFPRI (2009). Climate Change: Impacts on Agriculture and Costs of Adaptation. International Food Policy Research Institute, IFPRI, 2009. IPCC (2001). IPCC Third Assessment Report – Climate Change 2001: Summary for Policy Makers. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). IPCC (2007). Summary for policymakers. In: Climate Change 2007: The physical Science Basis. Contribution of working group I to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Solomon and co-workers (eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, USA. KARDA (1997). Diagnostic survey report of agro-forestry and land management practices in Kebbi State. Kebbi Agricultural and Rural Development Authority (KARDA), Kebbi State Nigeria. Muriwira, H. K., Mutiro, K., Nhamo, N., and Nzuma, J. K. (2001). Research Results on improving cattle manure in Tsholotsho and Shurugwi in Zimbabwe. In: Improving soil management options for women farmers in Malawi and Zimbabwe. Proceeding of a collaborator’s workshop on the DFID-supported project 13 – 15 September 2000. ICRISATBulawayo, Zimbabwe. Oluwasemire, K. O. (2004). Ecological Impact of changing rainfall pattern, soil processes and environmental pollution in the Nigerian Sudan and Northern Guinea Savannah Agroecological Zones. Nigerian Journal of Soil Research vol.5 2004:23-31. 9 Put, M., Verhagen, J., Veldhuizen, E. and Jellema, P. (2004). Climate Change in Dryland West Africa?: The empirical evidence of rainfall variability and trends. Environment & Policy, 2004, Volume 39, Part A, 27-32. Earth and Environmental Science, SpringerLink. Raji, B. A., Malgwi, W. B., Chude, V. O., and Berding, F. (2006). Integrated Indigenous Knowledge and Conventional Soil Science Approaches to Detailed Soil Survey in Kaduna State, Northern Nigeria. 18th World Congress of Soil Science, July 9-15, 2006 – Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA and FAO, Nigerian office, Abuja, Nigeria. Schmidhuber, J. and Tubiello, F. N. (2007). Global food security under climate change. William Easterling, Pennsylvania, University Park, P. A. Squires, V. and Tow, P. (1991). Dryland Farming: Systems Approach: An analysis of Dryland Agriculture in Australia. Oxford University press Australia. Pp 3-5. Usman S (2007). Sustainable soil management of the dryland soils of northern Nigeria. GRIN Publishing GmbH, Germany ISBN (Book): 978-3-640-92136-2. 10 Appendix 1 ASSESSMENT OF FARMER’S PERCEPTION ON YIELD REDUCTION AND SOIL QUALITY DETERIORATING IN KEBBI STATE “FACE-TO-FACE-VERBAL INTERVIEW” PhD project research BY SULEIMAN USMAN Natural Resource Institute University of Greenwich Chatham Maritime Central Avenue Kent ME7 4TB UK Q1. Ko kun fanhinci chanjin yanayi a wannan yaki naku? a) Aye b) A’a Have you notice climate change in your locality a) Yes b) No Q2. Ko chanjin yanayi yashafi gonankin noman ku? a) Aye b) A’a Is climate change affecting your agricultural farms? a) Yes b) No Q3. Wane irin babar banna ce ta haddasar? a) Gaigayar kasa b) Karamcin anfanin gona? What major environmental degradation it has caused so far? a) Erosion b) Yield reduction Q4. Minene imanin ku gameda abinda zai faru ga anfanim gonarkin ku shekara goma a gaba? a) Lalacewar yanayin kasa da kuma Karamci amfanin gona da kashi Saba’in a 2020 b) Lalacewar yanayin kasa da kuma Karamci amfanin gona da kashi Hamsin a 2020 c) Lalacewar yanayin kasa da kuma Karamci amfanin gona da kashi Talatin a 2020 What do you believe would happen to your farms by 2020 in term of soil-yield quality? a) Soil quality deteriorating and yield reduction by 70% b) Soil quality deteriorating and yield reduction by 50% c) Soil quality deteriorating and yield reduction by 30% 11 Appendix 2 Data analysis on farmer’s responses on question 2, 3 and 4 Data analysis: Percentages of individuals respond to questions been asked in the second round Argungu 43/53 = 0.81 0.81 x 100 =81% positive 6/53 = 0.11 0.11 x 100 =11% negative 4/53 = 0.075 0.075 x 100 =8% no respond Bagudo 46/59 = 0.78 0.78 x 100 = 78% 8/59 = 0.14 0.14 x 100 = 14% 5/59 = 0.08 0.08 x 100 = 8% Birnin Kebbi 55/62 = 0.88 0.88 x 100 = 88% 6/62 = 0.097 0.097 x 100 = 9.67 or 10% 1/62 = 0.016 0.016 x 100 = 1.6 or 2% Bui 68/68 = 1 1 x 100 = 100% 0/68 = 0 0 x 100 = 0% 0/68 = 0 0 x 100 = 0% Fakon-Sarki 35/38 = 0.92 0.92 x 100 = 92% 3/38 = 0.079 0.079 x 100 = 7.8 or 8% 0/38 = 0 0 x 100 = 0% Kangiwa 59/70 = 0.84 0.84 x 100 = 84% 8/70 = 0.112 0.114 x 100 = 12% 3/70 = 0.042 0.042 x 100 = 4% Tungar-Dangw. 50/76 = 0.657 0.657 x 100 = 65.7 or 66% 23/76 = 0.30 0.30 x 100 = 30% 3/76 = 0.039 0.039 x 100 = 3.9 or 4% Data analysis: Percentages of individuals respond to questions been asked in the third round Argungu 19/43 = 0.44 0.44 x 100 = 44% 13/43 = 0.30 0.30 x 100 = 30% 11/43 = 0.255 0.255 x 100 = 25.5 or 26% Bagudo 16/46 = 0.34 0.34 x 100 = 34.7 or 35% 27/46 =0.58 0.58 x 100 = 58% 3/46 = 0.065 0.065 x 100 = 6.5 or 7% Birnin Kebbi 26/55 = 0.47 0.47 x 100 = 47% Bui 33/68 = 0.48 0.48 x 100 = 48% Fakon-Sarki 12/35 = 0.34 0.34 x 100 = 34% Kangiwa 36/59 = 0.61 0.61 x 100 = 61% Tungar-D. 19/50 = 0.38 0.38 x 100 = 38% 21/55 = 0.38 0.38 x 100 = 38% 8/55 = 0.145 0.145 x 100 = 14.5 or 15% 25/68 =0.367 0.367 x 100 = 36.7 or 37% 10/68 =0.147 0.147 x 100 = 14.7 or 15% 17/35 =0.485 0.485 x 100 = 48.5 or 49% 6/35 = 0.17 0.17 x 100 = 17% 23/59 = 0.389 0.389 x 100 = 38.9 or 39% 0/59 = 0 0 x 100 = 0% 18/50 = 0.36 0.36 x 100 36% 13/50 = 0.26 0.26 x 100 = 26% Data analysis: Percentages of individuals respond to questions been asked in the fourth round Argungu 3/43 = 0.069 0.069 x 100 = 6.9 or 7% 14/43 = 0.325 0.325 x 100 = 32.5 or 33% 26/43 = 0.60 0.60 x 100 = 60% Bagudo 0/46 = 0 0 x 100 = 0% 19/46 = 0.41 0.41 x 100 = 41% 27/46 = 0.586 0.586 x 100 58.6 or 59% Birnin Kebbi 7/55 = 0.127 0.127 x 100 = 12.7 or 13% 23/55 = 0.418 0.418 x 100 = 41.8 or 42% 25/55 = 0.45 0.45 x 100 = 45% Bui 2/68 = 0.029 0.029 x 100 = 2.9 or 3% 21/68 = 0.308 0.308 x 100 = 30.8 or 31% 45/68 = 0.66 0.66 x 100 = 66% 12 Fakon-Sarki 6/35 = 0.17 0.17 x 100 = 17% 19/35 = 0.54 0.54 x 100 = 54% 10/35 = 0.285 0.285 x 100 = 28.5 or 29% Kangiwa 11/59 = 0.186 0.186 x 100 = 18.6 or 19% 33/59 = 0.559 0.559 x 100 = 55.9 or 56% 15/59 = 0.25 0.25 x 100 = 25% Tungar-D 1/50 = 0.02 0.02 x 100 = 2% 27/50 = 0.54 0.54 x 100 = 54% 22/50 = 0.44 0.44 x 100 = 44%